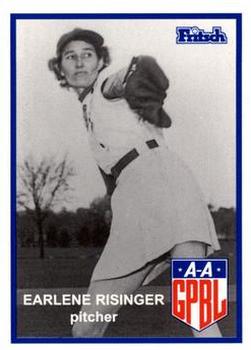

Earlene Risinger

At South High Field in Grand Rapids, Michigan, on Wednesday, September 9, 1953, Earlene “Beans” Risinger once again showed her durability and skill as a pitcher in the All-American Girls Baseball League (known today as the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League). In the Shaughnessy Playoffs, Risinger’s Grand Rapids Chicks, an improved team that finished in second place in the six-team circuit with a 62-44 record, had opened the postseason in Illinois with a 9-2 loss to the fourth-place Rockford Peaches (51-55 record). Facing elimination in the best-of-three semifinal series, the Chicks flew back to Grand Rapids for the second game. Pitching well with the chips down, Risinger blanked the Peaches on a two-hitter to win, 2-0.

At South High Field in Grand Rapids, Michigan, on Wednesday, September 9, 1953, Earlene “Beans” Risinger once again showed her durability and skill as a pitcher in the All-American Girls Baseball League (known today as the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League). In the Shaughnessy Playoffs, Risinger’s Grand Rapids Chicks, an improved team that finished in second place in the six-team circuit with a 62-44 record, had opened the postseason in Illinois with a 9-2 loss to the fourth-place Rockford Peaches (51-55 record). Facing elimination in the best-of-three semifinal series, the Chicks flew back to Grand Rapids for the second game. Pitching well with the chips down, Risinger blanked the Peaches on a two-hitter to win, 2-0.

Risinger’s clutch performance was backed by timely hitting and good fielding. The Chicks’ big hit was a single to left field in the seventh inning by Alma “Gabby” Ziegler, a .139 hitter in 1953. Ziegler drove home Jean Smith, who had singled and stolen second base. In the eighth, Dolores Moore knocked in the game’s final run with a bases-loaded sacrifice fly. The following evening, also at South Field, the Chicks’ Dottie Mueller went the distance and helped Grand Rapids advance by outlasting Rockford, 4-3.

In the league’s championship playoff, the Chicks met the third-place Kalamazoo, Michigan, Lassies (56-50), surprise winners in three games over the pennant-winning Fort Wayne, Indiana, Daisies (66-39). On Friday night, September 11, at South Field, Grand Rapids defeated Kalamazoo, 5-2. Traveling to Kalamazoo for the second game on Saturday night, Risinger, the lanky 6’2″ right-hander from Oklahoma, hurled a 4-3 victory. Finishing with a flourish, Beans, as she was known to teammates and opponents alike, struck out one of the league’s best hitters, Doris “Sammye” Sams, with the bases loaded and two outs in the seventh and final inning. Because that strikeout came against Sams, a five-time AAGPBL All-Star and a two-time Player of the Year, it became a highlight of Risinger’s unlikely career.

Earlene Risinger came from tiny Hess, Oklahoma, a village of less than two dozen people located in the southwest part of the state just above the Texas border. As a girl, she had no idea that women could play baseball professionally. Overcoming her fear of leaving home, Beans moved away to pitch in the All-American League from 1948 through the circuit’s final season, 1954. Her overall record was 73-80, but best season came in 1953, when she led the Chicks in victories with a 15-10 ledger, won twice in the playoffs, and helped her team win the AAGPBL Championship.

Born on March 20, 1927, the oldest child of Homer Francis “Soupy” and Lizzie Mae (Steen) Risinger, Earlene grew up in a sharecropping family surrounded by hard times. To earn money for shoes and clothes, she worked in the cotton fields. Her parents dubbed her “Beans” because she liked pork and beans for breakfast. Tall, slender, and attractive, with brown hair and hazel eyes, she loved sports. Beans especially liked watching her dad play first base on a sandlot team that played Sunday afternoons. Soupy taught his daughter to throw a baseball, and they played catch almost every day, which turned out to be the key to her future.

“Baseball ran in the Risinger family. That’s what I played with my cousins,” Beans recollected in a 1997 interview.

Although she was a good athlete, girls, as was the custom of the times, were not allowed to play baseball on the school team. Southside High did have girls’ teams in basketball and softball. But Earlene, too tall to play with most girls, liked to hang around and play baseball with the boys. Later, she was asked to coach first base and to warm up the pitchers. After graduating from Southside in 1945, three months before World War II ended, the 18-year-old had few prospects. For more than two years she worked in local cotton fields earning 50 cents an hour. Suddenly opportunity knocked.

Risinger recalled in 1997, “After graduation, here I was with no future. We never even thought about going to college, because there was no money for college. We were so poor that we couldn’t afford the newspaper. But one day in the spring of 1947, I was reading the day-old sports page at the country store. I always wished there would be girls’ baseball team, you know. You dream a lot when you’re a kid in a small town.

“That day I read about a traveling All-American Girls baseball team going to play an exhibition game in Oklahoma City on the way back north from spring training. I never dreamed such a league existed. I dropped a postcard to the sports editor, and he sent my card to the league’s headquarters in Chicago. Pretty soon I got a letter asking me to come to Oklahoma City for a try-out.

“It was a miracle I even heard about the league, not getting the newspaper or anything. But I was always interested in ballplayers like Allie Reynolds and, later, Mickey Mantle, because they were from Oklahoma.

“I went to Oklahoma City and tried out, and they decided to send me to Rockford, Illinois, to play for Bill Allington and the Peaches. I borrowed the money from a bank and started for Rockford on a train. By the time I got to Chicago and had to change trains, I was so homesick that I took the next train back to Hess. Luckily, I had enough money to get back home. Then I went back to the cotton fields to repay the bank loan.

“So I got this chance and muffed it, but in 1948 a second chance came. That year the league started a team in Springfield, Illinois, which was just a one-day bus ride. The manager of the team, Carson Bigbee, and the chaperone, Mary Rudis, took me under their wings, and I made it as a pitcher. Mary looked at me and said, ‘You’re too white!’ So she took me home, we went out in her back yard, and I got all sun-tanned!

“In 1948 the Chicago Colleens and the Springfield Sallies didn’t make it. We didn’t get enough attendance, so we played on the road for the second half of the season. My teammates with Springfield included ‘Jeep’ Stoll, Evelyn Wawryshyn, Erma Bergman, and Mildred Meachan. But we didn’t have enough good players.”

A hard-throwing pitcher for last-place Springfield, Risinger turned in a rookie record of 3-8 with a 3.35 ERA. During her first season as an All-American, the league converted to overhand pitching, a change from the sidearm delivery of 1947. However, the AAGPBL began in 1943 requiring underhand pitching, as used in softball, but switched to a modified sidearm delivery in 1946. Also, the pitching mound back was moved from 43 to 50 feet from home plate in 1948, a change that favored baseball-style pitchers. Further, the league used a “deadball” which steadily dropped from 12 inches in circumference in 1943 to 9.25 inches in 1954. Beginning around July 20, 1949, the All-American issued new 10-inch balls with red laces to accompany the increase in pitching distance from 50 to 55 feet. In addition to giving players a ball that was easier to see and livelier to hit, the game more nearly approximated baseball distances. Partly as a result, batting averages rose around the circuit. Further, the red laces contributed to convincing fans that the All-Americans were playing “real” baseball. In short, the AAGPBL played a hybrid form of softball and baseball that never really became baseball until (1) overhand pitching began in 1948, and (2) the ball changed to the red-seamed 10″ size in 1949.

“It was a blessing that I turned around and went home in 1947,” Beans explained in 1997, “because in 1948 they went to overhand pitching. I never pitched softball, so I couldn’t have pitched sidearm or underhand.

“In January of 1949 I was asked to go on the South American tour, and I jumped at the chance. During this tour they had two teams, the ‘Americanas’ and the ‘Cubanas.’ I was on the Americanas with Johnny Rawlings, and he taught me the finer points of pitching. All I knew before then was how to throw the ball. He was manager of the Chicks and he got me allocated to Grand Rapids. I played with them for the rest of my career.”

Asked what kind of pitches she threw most of the time, Beans replied, “High and tight!” Laughing, she said, “I had a good fastball and a ‘nickel’ curve. I could throw the ball past most of them, but I got accused of pitching ‘high and tight.’ When my fastball went in really good, it tailed in toward the right-handed batters.”

The city of Grand Rapids was proud to host one of the most successful franchises in the All-American League. The Chicks began in 1944 in Milwaukee. After finishing with a 40-19 record in the second half of the season (the league divided the 1943 and 1944 seasons into first and second halves to boost spectator interest), the team won the playoff championship. However, Milwaukee was a minor league city and home to the Triple-A Brewers, and the Chicks failed to draw good crowds. As a result, the franchise moved to Grand Rapids in 1945.

In the Furniture City, the Chicks prospered, finishing third in the All-American League with a 60-50 mark in 1945, second with a 71-41 record in 1946, and second with a 65-47 ledger in 1947. Further, Grand Rapids won the league’s championship in the 1947 Shaughnessy Series (first place versus third, second place versus fourth, and winner versus winner), lost in the final round of playoffs to the Rockford Peaches in 1949, and won a third playoff title in 1953.

During those years Risinger, a regular on the mound, fashioned three winning seasons. She produced her best season in 1953, compiling a 15-10 record, reversing her 1952 mark of 10-15, and enjoying career bests in ERA with 1.75 and strikeouts with 121. Overall, she posted an All-American lifetime record of 73-80, for a winning percentage of .477. Known as a tough pitcher to hit, she threw a good fastball, a curve, and a changeup, but she often walked more batters than she fanned. Her pitching statistics can be seen in the chart below:

| Year | Team | G | IP | H | R | ER | ERA | BB | SO | W-L | Pct |

| 1948 | Spr | 22 | 129 | 91 | 68 | 38 | 3.35 | 62 | 69 | 3-8 | .273 |

| 1949 | GR | 30 | 234 | 146 | 90 | 61 | 2.35 | 143 | 116 | 15-12 | .556 |

| 1950 | GR | 31 | 231 | 201 | 76 | 61 | 2.38 | 87 | 90 | 14-13 | .519 |

| 1951 | GR | 24 | 177 | 116 | 66 | 42 | 2.14 | 77 | 65 | 9-9 | .500 |

| 1952 | GR | 27 | 192 | 150 | 72 | 50 | 2.34 | 97 | 82 | 10-15 | .400 |

| 1953 | GR | 30 | 231 | 151 | 66 | 45 | 1.75 | 95 | 121 | 5-10 | .600 |

| 1954 | GR | 23 | 153 | 170 | 87 | 69 | 4.06 | 58 | 38 | 7-13 | .350 |

| Total | 187 | 1347 | 1025 | 525 | 376 | 2.51 | 619 | 581 | 73-80 | .477 |

Sammy Sams commented in 1998: “Beans was fairly tall with those long arms and legs. So when she started to pitch and uncoiled and hit her stride, the batter was darn near shaking hands with her. You might say, in your face. She had a good fastball. I remember it well!”

Risinger, who batted .171 lifetime, connected for four doubles and a triple, but no home runs, in her seven seasons. On August 10, 1952, in a Monday night marathon against Kalamazoo, Grand Rapids, with Risinger hurling, prevailed in 13 innings, 3-2. The homestanding Chicks won in the bottom of the thirteenth when Jean Geissinger singled, moved to second on a sacrifice, advanced to third on a groundout, and scored the game-winning marker when Risinger singled to short right field, her second hit in six trips. Earlier, Risinger belted her only career triple, but the Lassies’ Jean Marlowe retired the side, leaving the lanky right-hander stranded on third.

Beans remembered, “I couldn’t hit all that well, and I was a slow runner, so all I did was pitch. One time I really connected and hit the ball all the way to the stands. Anyone else would have had a home run, but I just barely made it to third base.

“Our bookkeeper was in the stands with his son. Afterward, the father told me that his boy looked up and said, ‘Daddy, why don’t she run?’”

Beans, who batted .203 in 30 games in 1953, laughed at the memory.

The quality of play in the All-American League remained first-rate as the years passed, but the number of teams declined. After 1948, when the AAGPBL reached a peak of ten teams and generated a record league attendance of 910,000, other interests and forms of recreation began to claim the attention of many fans. Those attractions included more popular programs on television; more major league baseball games on TV; and more participation by people in golf, tennis, badminton, and other individual games.

On the negative side, while the Springfield Sallies and the Chicago Colleens functioned as rookie touring teams and played an extensive exhibition schedule against each other in 1949 and 1950, the two clubs were dropped in 1951 because of the league’s lack of funds. Thereafter, the AAGPBL had no “minor league” or training teams as a means of recruiting new female baseball players, and good pitchers were particularly hard to find. Further, Americans in the early 1950s witnessed the stalemate in the Korean War, the increase of anti-Communist fears known as “McCarthyism,” the boom in production and sales of automobiles, and the growth of the population into new suburbs.

At the same time, women increasingly faced social pressures to conform to traditional gender roles. In other words, the American woman’s “place” was in the home with her family. As actress Debbie Reynolds observed in the 1955 movie The Tender Trap, “A woman isn’t really a woman until she’s been married and had children.” These trends also meant that many Americans developed new recreational interests, enjoyed access to a variety of far-flung activities, and spent less time going to local ballparks, although major league baseball remained popular.

The All-American League, continuing to change and evolve within the nation’s increasingly conservative culture, dropped from eight teams in 1949, 1950, and 1951 to six in 1952 and 1953. Only five clubs competed in 1954. In 1952 and 1953, the league featured teams from Grand Rapids, Rockford, Fort Wayne, Kalamazoo, along with the South Bend Blue Sox and the Muskegon Belles, a franchise that played from 1943 through 1950 in Racine, Wisconsin.

In 1952 the league’s financial problems were illustrated by an incident in Grand Rapids. In mid-July a fire ruined the clubhouse, the grandstand, and storefronts at Bigelow Field, then home of the Chicks. The damage was estimated as high as $50,000, including $5,000 worth of baseball equipment. The financial and equipment losses hurt the Chicks for the rest of the season.

Beans recollected, “We lost everything, uniforms, gloves, cleats, and all. For our home games we had to wear the old uniforms of the Peoria Redwings, a team that went under after the 1951 season. Our caps didn’t even match. Attendance was down, and the club didn’t have the money to buy new uniforms or caps. But we kept doing the best that we could.”

Regardless, Beans fondly recalled her career highlight from the playoffs of 1953. In early September, Grand Rapids wrapped up second place and faced fourth-place Rockford in the semifinal round. The slugging Daisies, after maintaining the top spot against a late-season surge by the Chicks–who won nine straight games before losing their finale, faced third-place Kalamazoo in the league’s other semifinal.

On Tuesday, September 8, the Chicks boarded two planes and flew to Rockford for the opener in a best-of-three series. The Grand Rapids manager, “Woody” English, announced his lineup would feature Eleanor Moore on the mound; Marilyn Jenkins, the former bat girl, behind home plate; Inez “Lefty” Voyce at first base; Dolores Moore at second; Gabby Ziegler at short; Renae Youngberg at third; Doris “Sadie” Satterfield in left field; Jean Smith in center; and Joyce Ricketts–the only player who appeared in all 110 of the Chicks’ games that year–in right. Pitchers for the second game and, if necessary, the third contest would be Mary Lou Studnicka and Risinger.

Rockford won the first tilt, 9-2, by rapping 13 hits off Moore and Studnicka. Flying home on Wednesday, Grand Rapids faced elimination. Instead, Risinger rose to the challenge and whitewashed Rockford, 2-0, as indicated above. When Dot Mueller pitched her club to another victory on Thursday, the Chicks advanced to the best-of-three championship round against Kalamazoo, which had eliminated Fort Wayne.

In game one of the finals at South Field, Grand Rapids emerged a 5-2 winner, thanks to the hurling of Mary Lou Studnicka–who received strong relief help from Eleanor Moore in the ninth. The Chicks scored solo runs in the first and the third innings, and Kazoo scored twice in the third to tie the game, 2-2. The home team rallied for three in the fourth, loading the bases via an infield single by Moore, Studnicka’s bunt–which was thrown away for an error, and a walk to Jean Smith. Ziegler drove home one run with a sacrifice fly to left. Satterfield bounced to pitcher Gloria Cordes, who fumbled it, loading the bases. Voyce lofted a long sacrifice fly to foul territory in right, and Joyce Ricketts singled to score the third run.

With two Lassie runners on board in the top of the ninth, Eleanor Moore was summoned to the mound. She promptly retired the side, striking out Isabel Alvarez, inducing “Dottie” Schroeder to pop to the shortstop, and getting June Peppas on a grounder to second base.

On Saturday evening, September 12, at CAA Field in Kalamazoo, Risinger pitched the biggest game of her career. As luck would have it, the game was limited to seven innings by mutual consent–due to cold, misty weather, as the temperature fell below 40 degrees by game time. Undaunted, Beans hurled a steady game. The Chicks gave her a one-run lead in the second inning. Grand Rapids wrapped up the scoring by producing three runs in the sixth, keyed by a two-run double off the bat of Joyce Ricketts.

Risinger yielded only one extra-base hit, a solo home run by Doris Sams during Kalamazoo’s two-run rally in the sixth. With two outs, Sammye blasted a fastball over the left field fence. Jeep Stoll followed with a single, and Betty Francis walked. Jean Lovell singled to all the way to the right field fence, scoring Stoll, but Francis, rounding third base, was caught off the bag, thanks to Ricketts’ strong throw from right.

In the seventh, Kalamazoo’s “Dottie” Naum, who allowed only five hits, retired the Chicks, and the Lassies tried to rally again. Fern Shollenberger singled to the right field fence to open the bottom of the inning. Undaunted, Risinger retired Terry Rukavina and Naum for the first two outs. Beans, however, temporarily losing her control, issued her third and fourth free passes to Dottie Schroeder and June Peppas. With the bases full of Lassies, Sams–a dangerous slugger who led the circuit with 12 home runs in 1952, but hit only one regular season homer in 1953–struck out on three straight fastballs. Thus, Risinger’s ninth strikeout of the chilly night, and perhaps the most important whiff she ever recorded, gave Grand Rapids the victory and the All-American Championship.

Sams recalled the strikeout in a 1987 story for the Grand Rapids Press: “I remember swinging at two bad balls. She [Risinger] is a good pitcher. I’d say she was pretty wild that night. But she put one right down the heart to me, the first one.

“Then she put down two shoulder balls that I just suckered in on, and that’s all she wrote. She had been walking all these people. Then she just turned around and laid it in there.” The Knoxville lassie had belted the home run in her previous at-bat, and it boosted her confidence. Sammye said, “Having hit a home run before, I thought, ‘Oh, well, I’ve got it made.’ That turned out to be quite a joke. She really turned loose with those [pitches]. I don’t remember even seeing those go across the plate.”

Reflecting on that final game in 1998, Sammye observed, “People remember that I struck out in my last at-bat in the All-American League. But nobody says anything about me helping my team by hitting a home run in the previous at-bat!”

“In that game,” Risinger reflected, “the temperature was not much above freezing, the manager had gotten kicked out of the game, and Gabby Ziegler, the captain, was acting as manager. The bases were loaded in the seventh and I was getting wild. Up came Sammye to bat, and here comes Gabby, who was about five-foot tall.

“She looked up at me and said, ‘Well, Beansie, can you get her out?’

“I said, ‘I guess so,’ and I struck Sammye out with a fastball!”

Risinger and the Chicks returned in 1954 for what turned out to be the league’s swan song. The Chicks finished third of five teams with a 46-45 record, but in the first round of Shaughnessy Playoffs, regular-season champion Fort Wayne (54-40) won on a forfeit from Grand Rapids.

A dispute erupted before the two teams had played the opening game at South Field. Due to an injury suffered by Fort Wayne’s regular catcher, league officials voted to allow the Daisies to add Rockford All-Star Ruth Richard to the roster. Tempers flared in Grand Rapids. The Chicks, claiming that using a new player was unfair, played the first game under protest–but won, 8-7. Attempting to resolve the matter the following night in Fort Wayne, Woody English and Daisy pilot Bill Allington got into a fight at home plate. Later, English’s team voted not to play, so the Chicks forfeited–allowing the Daisies to advance to the championship round. In the end, Kalamazoo won the last All-American Championship by defeating Fort Wayne in five games.

During her early years in Grand Rapids, Risinger worked at Jordan Buick, because the owner would give her time off to play baseball. Following her final season, she trained to become an x-ray technician for one year at the Butterworth Hospital in Grand Rapids. In 1955 she left Butterworth to take x-rays for three orthopedic surgeons, and she continued that service until 1969. Leaving the x-ray business, she served as an orthopedic assistant in a local doctor’s office for more than twenty years, retiring in 1991. Starting with her baseball years, Beans liked living in Michigan, including the summers, which she often enjoyed at her house in Grand Haven. As she once phrased it, “Caring for others is the best thing one can do in life.” Still, the Oklahoma native enjoyed returning to her roots to visit family and friends in Hess where, in 1973, she was inducted into the Jackson County Sports Hall of Fame. Hess would always be her home.

Risinger commented in 1997, “A lot of people say the league really made their lives. Well, it did for me. It got me out of the poverty in Oklahoma all the way to Grand Rapids. I live there to this day. That’s where all my friends are. I wouldn’t trade my experiences for anything in the world. I retired in 1991, and I love going to the All-American Reunions.”

Earlene “Beans” Risinger passed away July 29, 2008, at the Plantation Village Nursing Home in Altus. Survived by four brothers and numerous nephews, nieces, and cousins, she was buried in Hess Cemetery.

A good pitcher during the league’s last six years, Beans Risinger achieved a great deal along her journey from rural Oklahoma. A talented female athlete who dreamed the baseball dream, she ended up not only playing in the historic All-American Girls Baseball League, the only professional league ever to play women’s baseball, but also she helped her team win the 1953 championship by striking out one of the circuit’s great players. Thus, the baseball career of Beans Risinger, an unlikely hero, provided another illustration of the first-class women whose diamond skills made a winner out of the storied All-American League.

Sources

This is an expanded version of my Beans Risinger story as posted on the AAGPBL web site in the year 2000. I first interviewed Beans at the Myrtle Beach Reunion on October 24, 1997, and we exchanged several subsequent letters. I also used Risinger’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, and I found material about her, including her official stat sheet, in the AAGPBL files at the Northern Indiana Center for History in South Bend. I have also read pertinent section of the Grand Rapids Press and the Kalamazoo Gazette (about Sams) on microfilm

Books:

Leslie A. Heaphy and Mel A. May, eds., Encyclopedia of Women in Baseball (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2006), p. 245

Steven M. Gillon, The American Paradox: A History of the United States Since 1945 (2nd ed., New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2007), see pp. 117-120, “Women During the 1950s”

Merrie Fidler, The Origins and History of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2006), is the best history of the All-American League, including information about how the league’s structure, rules, and play on the field evolved over twelve years of operation

Newspapers:

Grand Rapids Press:

Roscoe D. Bennett, “Chicks’ Lineup for [1951] Opener About Set,” 1951.

Bennett, “Chicks Slow Down Belles for 11-1 Triumph,” .Sept. 4, 1953

Bennett, “Chicks Wing Way to Playoff Site,” .Sept. 8, 1953

Bennett, “Risinger Chicks’ Last Hope in Girls Loop Playoffs,” .Sept. 9, 1953

Bennett, “Risinger Blanks Rockford and Chicks Await Kalamazoo,” .Sept. 10, 1953

Bennett, “Chicks, Kalamazoo Open Playoff title Series,” .Sept. 11, 1953

Bennett, “Chicks Cop Playoff Finals Opener; Set for No. 2 in Kazoo,” .Sept. 12, 1953

“Chicks Win Playoffs Championship,” .Sept. 14, 1953

Elizabeth Slowik, “The Last Pitch [of 1953],” .May 17, 1987, quoted Risinger, Sams, catcher Marilyn Jenkins, and chaperone Dorothy Hunter

Kalamazoo Gazette:

“Chicks’ Bigelow Field Burns,” July 16, 1952

“Grand Rapids Asks Transfer After Fire,” July 17, 1952

“Grand Rapids Chicks Edge Lassies, 4 to 3 / Naum Loses Final Game to Risinger,” September 13, 1953

Articles:

Leo Kelly, “‘Beans’ Risinger Starred in Women’s Pro Baseball,” Altus (OK) Times-Democrat, October 1988, and Risinger, typed statement, “Earlene ‘Beans’ Risinger,” Dec. 1975, copies of both in Risinger’s Baseball HOF File

Web site: See the AAGPBL web site for a wealth of information about the All-American League and the players: http://www.aagpbl.org/

Full Name

Risinger

Born

March 20, 1927 at Hess, OK (US)

Died

July 29, 2008 at Altus, OK (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.