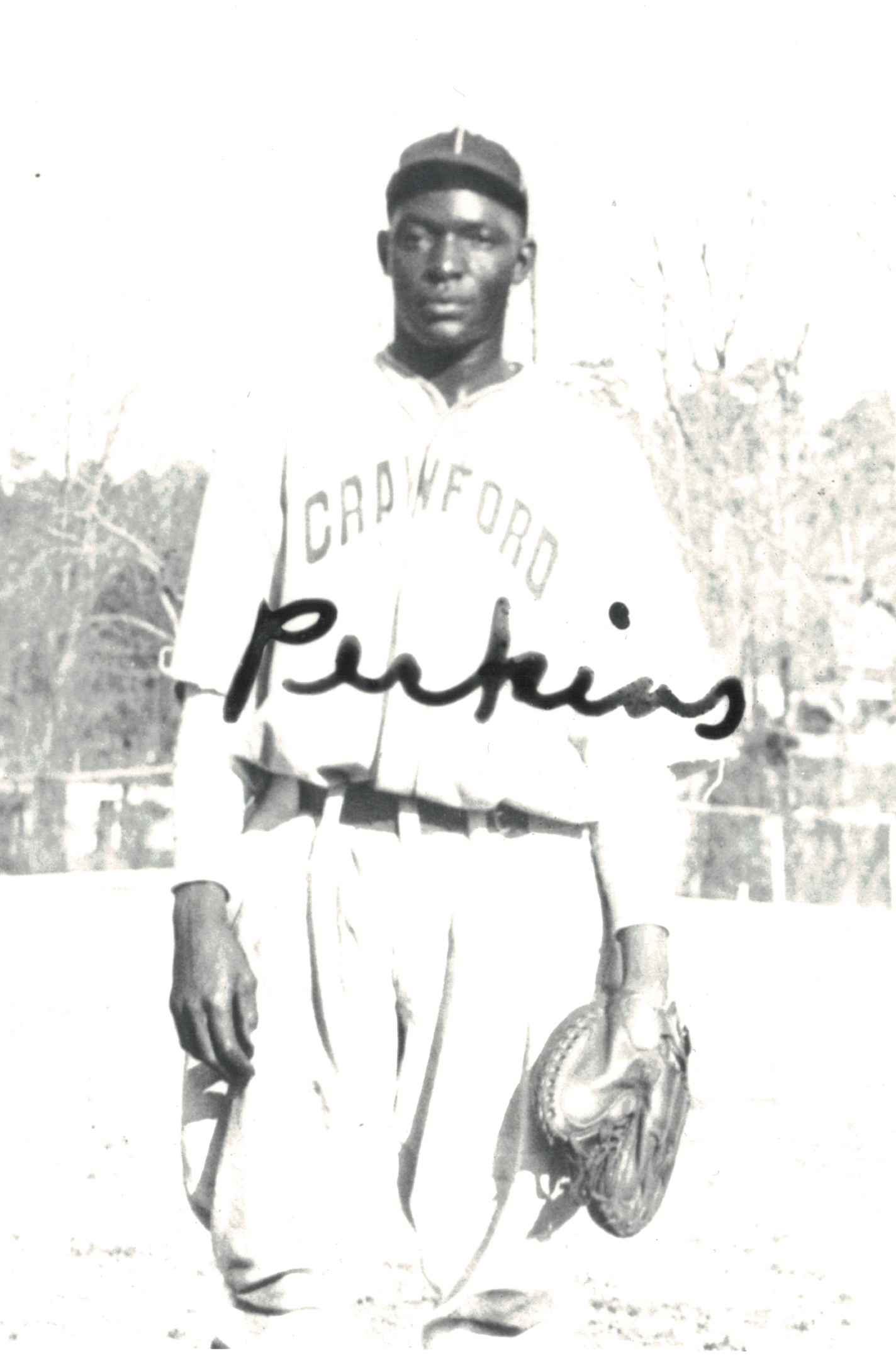

Bill Perkins

“My catcher was George Perkins, who handled a pitcher like nobody’s business,” wrote Satchel Paige.1 Bill Perkins, also known as William, George, and even Cy on occasion, was a catcher in the Negro Leagues for two decades and was the legendary Paige’s favorite target behind the plate.

“My catcher was George Perkins, who handled a pitcher like nobody’s business,” wrote Satchel Paige.1 Bill Perkins, also known as William, George, and even Cy on occasion, was a catcher in the Negro Leagues for two decades and was the legendary Paige’s favorite target behind the plate.

When Paige was first notified of his induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame, he mentioned other Hall-worthy stars from the Negro Leagues. “Besides Josh Gibson, there was Frank Duncan, my catcher on the Monarchs, and another catcher, William Perkins of Birmingham, and outfielder Oscar Charleston, who were great, just to mention a few.”2

Perkins is not remembered as an all-time great in the Negro Leagues, possibly because Gibson was his teammate for several seasons so he was not even the greatest catcher on his own team. If circumstances had been different, the name Bill Perkins might be recognized today, but his endorsement by Paige, whom he followed from Birmingham to Cleveland to Pittsburgh and the Dominican Republic, is enough to confirm that Perkins was an excellent catcher.

William George Perkins was born on January 26, 1906, in Dawson, in southwest Georgia, to Class and Lizzie (Dennison) Perkins. Class was a farmer, and William had two older sisters, Rosa and Susie. Grammar school was the highest education William received. Neither parent could read or write, according to the 1900 census.

Perkins first played baseball professionally in 1928. As the season opener approached, the Birmingham Reporter wrote that Birmingham Black Barons manager Poindexter Williams “has the find of the season in young Perkins, catcher, who receives, throws and bats with any catcher in this section of the country.” The paper also mentioned Perkins’s new batterymate, “Satchel, better known as Page [sic].”3 It was the beginning of a historic relationship, and one has to wonder what Paige’s career might have been without the presence of Perkins. “Finally he had a receiver who understood him,” wrote Paige’s biographer, Larry Tye. “The two shared a sense of swagger and humor, with the catcher supposedly emblazoning THOU SHALT NOT STEAL across his chest protector much as Satchel allegedly wrote FASTBALL on the sole of his elongated left shoe. Perkins knew how to extract the most from the temperamental pitcher.”4

When the duo first met in Birmingham, Perkins asked what signs Paige wanted him to give. “There ain’t any need for signs, I guess,” Paige told him. “I don’t take to them too good. Anyway, I’m the easiest guy in the world to catch. All you have to do is show me a glove and hold it still. I’ll hit it. I could see George didn’t believe me. Neither did any of the other Black Barons standing around, so I had them hold a couple of bats about six inches apart. I fired my fastball right through that space. From then on we went without signs. ‘You sure think a lot of yourself’ is all George would say.”5

Perkins was also behind the plate for Poindexter’s no-hitter against Chicago on June 27.6 Birmingham finished in the middle of the pack in the NNL.

In 1929 Perkins was listed among returning Black Barons players, but was acquired in April by the Brooklyn Royal Giants, an independent black club. Ted Page remembered the encounter when Brooklyn played against a local team in Dawson, Georgia, Perkins’s hometown. “Perkins was the idol of the town,” Page recalled. “They had built a ball park for him out of old logs and broken-down doors. Everybody came to watch the ball games and the sheriff was the ticket taker. Well, we went down in spring training and saw him and wanted to take him back north, but the sheriff said, ‘No, he has to stay here, we built a ball park for him. He said if we left town in the morning and his man – he didn’t say ‘man,’ I’ll let you guess what he said – if his man wasn’t there, we better not be in Georgia. And we weren’t. We hid Perkins under the bus and drove right past the sheriff sitting right in front of the store.”7

Near the end of the season, Perkins was acquired by John Henry “Pop” Lloyd’s Lincoln Giants of the Eastern Colored League.8 In 1930 Perkins returned to Birmingham, a relief to the local fans as Perkins was “considered by many to be one of the best in the game today,” wrote the Birmingham Reporter. “The owners made a master stroke when they obtained Perkins again, and one that pleases the fans, for Perkins was very popular with the fans here, because of his hard, earnest work and the ability to give the old pill a ride.”9 When Birmingham traveled to St. Louis for a series with the Stars, the Chicago Defender heaped praise on Perkins as “one of the greatest catchers in the South. This lad has been the sensation of the whole Birmingham team with the great way in which he holds down the backstopping position for his team. He can hit with the best of them, too.”10

Perkins returned to Birmingham in 1931. Juan “Tetelo” Vargas of the barnstorming Cuban House of David club (a copycat of the Michigan-based team of the religious community in which men would not shave) stole six bases “each time beating perfect pegs from catcher Perkins,” reported the Philadelphia Tribune.11 Perkins did not stay long in Birmingham as he briefly returned to the Brooklyn Royal Giants, then was acquired by the Cleveland Cubs of the NNL, where he rejoined Paige.12 Again on the move, the independent Pittsburgh Crawfords acquired the Paige-Perkins battery in June.13 Perkins made immediate impressions. “Perkins attracted considerable attention with his work behind the plate here in the series with the Grays,” wrote the Pittsburgh Courier. “His great throwing arm and a natural receiving stamps him as a real find.”14 The Philadelphia Tribune added later, “A genuine sensation is Perkins. He is a hustling little chatter box and an ace maskman in the bargain. Without a doubt Perkins is the most colorful performer seen here in recent years.”15 While he was a favorite of Paige, a 1932 article boasted of Perkins’ work with another pitcher, Sam Streeter, saying, “[T]he pair formed the Crawfords’ most dependable battery.”16

Perkins and Paige returned to the Crawfords in 1932 and delighted Birmingham fans on a spring-training stop where they “have a large following of fans here,” wrote the Atlanta Daily World.17 The Pittsburgh Courier praised Perkins for adding “more zip and chatter to his topnotch program of last year. He is a sure shot backstop and continues to slam the old apple to the outer boundaries.”18 Perkins’s first stint with the Crawfords was short-lived as he briefly played for the Cleveland Stars of the East-West League, then finished the season with the Homestead Grays, also of the EWL.19 Perkins “is playing the game of his life with the Homesteaders,” wrote the Courier in August. “‘Perk’ has led the team in home runs and hits during the past couple of weeks and is smashing the ball with a vengeance.”20 When the season concluded, Perkins joined the Monroe (Louisiana) Monarchs for a trip to Mexico.21

In 1933 Perkins returned to the Crawfords, who were now in the Negro National League. The Chicago Defender dubbed him “The Pride of the South,” who was “the peppiest and surest receiver to bob up in recent years.” Waiting in the wings, however, was the young catcher Josh Gibson, whom the paper called “the hardest hitter in baseball.”22 Reports from spring training must have given fans back in Pittsburgh visions of the Yankees’ Murderers’ Row as, in 10 games, Perkins slammed five home runs and Gibson three, prompting a Courier headline: “Crawfords May Have Best Club in History.”23 The Crawfords would need to deal with the “lively battle” of having two of the best catchers in all of Negro League baseball on the club.24 The Crawfords’ powerful lineup held true to predictions and when the Courier published statistics at the end of June, the Crawfords’ four top hitters were Charleston (.450), Cool Papa Bell (.379) Gibson (.378), and Perkins (.344), with Charleston and Gibson slamming four home runs and Perkins four triples.25 To get both bats into the lineup, player-manager Charleston would at times play either Perkins or Gibson in the outfield or first base while the other caught. The Crawfords were awarded the NNL championship.26

Despite being under contract with the Crawfords in 1934, Perkins held out much of the year and became manager of his hometown independent Birmingham Black Giants club.27 Later, Perkins and Paige joined the House of David club in time for the Denver Post’s semipro tournament. Playing well for the House of David propelled fans to still vote in large numbers for Perkins for the East-West Game, the Negro Leagues’ equivalent to the white All-Star Game.28 Perkins played in the game as a reserve and Paige got the win in relief. The Crawfords failed to repeat as NNL champions.

The 1935 Crawfords returned with a vengeance, becoming what many consider one of the greatest Negro League teams of all time. In statistics published at the end of July, Perkins was credited with a .362 batting average.29 The Crawfords won back-to-back championships in 1935-36.

Both Perkins and Paige created a stir when they jumped to the Dominican Republic team in the early part of 1937 in an apparent “raid” of Negro League teams.30 They both played for a club in Santo Domingo. Paige, Perkins, and others were barred from the NNL by President Gus Greenlee for these actions.31 The Santo Domingo club went on to win the Denver Post Tournament. In March of 1938, the “jumpers” were reinstated by the NNL and were penalized by losing one month’s salary. Paige was returned to the Crawfords while Perkins was traded to the Philadelphia Stars.32 Perkins spent 1938-39 as the starting catcher for the Stars.

Early in the 1940 season, Perkins was signed by the Baltimore Elites “to bolster the backstop department, which has been manned chiefly by the youthful Roy Campanello [sic],” wrote Art Carter of the Baltimore Afro-American.33 Perkins became the new mentor for the 18-year-old future Hall of Famer, Campanella taking over from the departed Biz Mackey. Although Perkins was in his 13th season, a columnist in the New York Amsterdam News was highly impressed with the veteran. With talk increasing of the national pastime needing to integrate, the writer felt that Perkins’s skills had often been overlooked. He said Perkins exhibited “the same fire, dependability and showmanship he displayed when he caught Satchel’s hottest offerings. Perkins has seldom been mentioned by the scribes in picking their players for possible candidates for the major leagues. Paige has. Paige may be slowing up. Perkins isn’t.”34 Perkins was the starting catcher for the East in the East-West Game in August, his second appearance.35

In the offseason Perkins was dealt to the New York Black Yankees, but he never played for the team; instead, he crossed the border and played for Mexico City. A July article mentioned Perkins batting .344 at the time.36 Perkins also played for Mayaguez in Puerto Rico’s Liga Semipro league until returning home to Birmingham to care for his ailing mother. Perkins apparently was out of baseball and remained in Birmingham until he was drafted into the US Army in the midst of World War II.37

Perkins returned from military service in 1945 and played for the New York Black Yankees. He was released in the summer and signed on with the Philadelphia Stars. He spent 1947-1948, the final seasons in his 20-year career, with the Baltimore Elite Giants. In 1949 he was retired and back in Birmingham.38

Perkins married Jessie Hatch, a schoolteacher originally from Alabama, in 1931. In 1934 their only child, William Jr., was born. The Perkinses ran a restaurant in Birmingham for a while.39 Bill Perkins died on January 24, 1958, and was buried in Dawson, Georgia. “His death is believed to have resulted from a heart attack,” his obituary reported. “He had walked home and entered the bathroom, where he dropped off dead, it was said. Mr. Perkins had not been in his usual health after coming home from World War II.”40 He and Jessie were divorced at the time of his death. “They were divorced about 1947 shortly after Mr. Perkins was honorably discharged from the Army,” his obituary stated. “Mrs. Perkins is currently engaged in the café and hotel business.”41

Perkins spent five offseasons playing in Cuba: Santa Clara (1935-36, 1936-37, 1937-38), Cuba (1938-39) and Cienfuegos (1940-41). Statistics supplied by the Ashland Collection through the Baseball Hall of Fame credit Perkins as a .288 hitter with nine home runs over that span. The Seamheads Negro League Database credits him with a career batting average of .267, but such incomplete records fail to tell much of a story of his career. As his obituary noted, “His name ranked along with Josh Gibson, Bizz [sic] Mackey and other luminaries of the mask and breastpad.”42

Sources

Ancestry.com. US World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946.

Ancestry.com. US WWII Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947.

Baseball-reference.com.

Birmingham (Alabama) Public Library.

Cassidy Lent, A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, Baseball Hall of Fame.

New York Passenger and Crew Lists, 1909, 1925-1957, database with images, FamilySearch.org

Seamheads Negro League Database

Notes

1 LeRoy “Satchel” Paige and David Lipman, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever: A Great Baseball Player Tells the Hilarious Story Behind the Legend (New York: Doubleday & Company, 1962), 47.

2 Associated Press, “Baseball to Honor Black Players in the Hall of Fame,” Portsmouth (Ohio) Times, February 4, 1971: 20.

3 “Black Barons Play Camp Benning Here Next Week,” Birmingham Reporter, April 14, 1928: 7.

4 Larry Tye, Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend (New York: Random House, 2010), 46.

5 Paige and Lipman, 47-48.

6 “Poindexter Hurls No-Hit No-Run Game,” Chicago Defender, July 7, 1928: 8.

7 John B. Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues, revised ed. (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 2010), 157.

8 “Royal Giants Heading East,” New York Amsterdam News, April 17, 1929: 9; “St. Louis Stars to Play Lincoln Gts,” Chicago Defender, September 28, 1929: 8.

9 “Black Barons Leave Tuesday for Training Camp,” Birmingham Reporter, March 29, 1930: 7.

10 “Birmingham to Cross Bats with St. Louis,” Chicago Defender, August 9, 1930: 8.

11 “10 Steals for Bearded Star as Mates Win,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 7, 1931: 11.

12 “Brooklyn Royals Lose One, Then Tie,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 14, 1931: 11; “Louisville Is Loser, 3 to 2, at Cleveland,” Chicago Defender, June 20, 1931: 9; “Fix Upp [sic] Cleveland Park,” Chicago Defender, May 16, 1931: 9.

13 “Crawfords Sign New Stars,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 27, 1931: A5.

14 “Crawfords Sign New Stars.”

15 “Diamond Dust,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 20, 1931: 10.

16 “Catches ’Em,” News Journal and Guide (Norfolk, Virginia), March 19, 1932: 12.

17 Wilson L. Driver, “Hits & Bits,” Atlanta Daily World, April 10, 1932: 5.

18 “Crawfords Back, Set for Test,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 30, 1932: A5.

19 “Cleveland and Grays Defeat Crawfords,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 25, 1932: 14; “Works Hard,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 9, 1932: A5.

20 “Perkins Setting Pace with Grays,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 6, 1932: A4.

21 “Grays End Season with Win; Set Mark,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 1, 1932: A4.

22 “Crawfords Out to Better 1932 Mark,” Chicago Defender, April 15, 1933: 8.

23 “Crawfords May Have Best Club In History: Team Hits Stride on Invasion Of Dixie,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 15, 1933: A4; “Crawfords Win Ten in South,” Baltimore Afro-American, April 29, 1933: 16.

24 “Sez ‘Chez,’” Pittsburgh Courier, April 29, 1933: A5.

25 “‘Texas’ Burnett Leads Hitters, Summary Shows,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 24, 1933: A4.

26 The pennant was won in controversy. Gus Greenlee was both the owner of the Crawfords and the president of the NNL. One might thus argue that he had a conflict of interest. “Greenlee did not carry out plans for a playoff, though his decision was not made until the Crawfords had rallied to win the second-half title by sweeping a thrilling doubleheader against the Nashville Elite Giants on the last day of the season. … When the Crawfords took the nightcap, Greenlee believed no more proof was needed to crown his boys as the league’s first champions, which he declared them two months later. Gus left no room for Robert Cole, whose American Giants had won the first half, to challenge the decision; again, Greenlee’s word was law. Besides, Gus had not formed this circuit to play a World Series, he did it to prove that black businessmen could make a profit in baseball, as that would be the most effective lever in prying open the majors’ closed door.” Mark Ribowsky, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues 1884-1955 (New York: Birch Lane Press, 1995), 178.

27 “Deny Perkins Was Holding Out Over a Salary Dispute,” Chicago Defender, April 7, 1934: 16.

28 The Pittsburgh Courier listed Perkins as receiving just under 5,000 votes, placing him fourth among East catchers and just under 500 votes fewer than first-place Gibson; “Final Standings – the East,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 25, 1934: A5; “Perkins Will Return to the Crawfords’ 9,” Chicago Defender, August 11, 1934: 17.

29 “National Association Batting Averages,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 20, 1935: 21.

30 “Paige Jumps Crawfords; Perkins Also Said to Have Skipped Loop; Both Believed with Semipro Nines in Canada,” Chicago Defender, May 1, 1937: 13.

31 “Satchell Paige Will Be Barred from N.N. League,” News Journal and Guide (Norfolk, Virginia), May 8, 1937: 18.

32 “NNL Reinstates ‘Jumpers’; New D.C. Club Is Admitted,” Afro-American (Baltimore), March 12, 1938: 18; “Player Deals Feature of N.N. League Meeting: Taylor, Paige to Craws,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 12, 1938: 17.

33 Art Carter, “Elites Play Stars Twin Bill Sunday,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 10, 1940: 23.

34 “Confidentially Yours, Daniel,” New York Amsterdam News, June 1, 1940: 14.

35 Art Carter, “East Blanks West, 11-0, in Baseball’s Big Classic,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 24, 1940: 19.

36 “Elites and Yanks Swap Players,” Baltimore Afro-American, January 11, 1941: 19; “Josh Gibson, Snook Wellmaker Among Negroes in Mexico,” Atlanta Daily World, May 5, 1941: 5; “U.S. Ballplayers Muck up the Mexican Loop,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 24, 1941: 9.

37 Dan Burley, “Terris MacDuffie, Pitching Star of Homestead Grays, Tells of Discrimination Against Negro Players in Cuba: White Minor League Stars Taking Over in Their Places,” New York Amsterdam Star-News, January 17, 1942: 13; Emory O. Jackson, “Hits & Bits,” Atlanta Daily World, August 7, 1942: 5; Perkins registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, with his current residence being listed as Los Angeles. His listed employer was Tom Wilson, president of the Negro National League. He was 5-feet-9 and 176 pounds. Military records show Perkins enlisting on July 31, 1942, at Fort Benning, Georgia.

38 Emory O. Jackson, “Hits & Bits,” Atlanta World Daily, April 29, 1949: 7.

39 Brent Kelley, The Negro Leagues Revisited: Conversations with 66 More Baseball Heroes (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000), 183.

40 “William Perkins, Famed Baseball Catcher, Dies,” Birmingham World, January 29, 1958: 6.

41 “William Perkins, Famed Baseball Catcher, Dies.”

42 “William Perkins, Famed Baseball Catcher, Dies.”

Full Name

William George Perkins

Born

January 26, 1906 at Dawson, GA (US)

Died

January 24, 1958 at Birmingham, AL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.