May 29, 1875: The first recorded no-hitter: Princeton vs. Yale

“Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah! Tiger! Hish! Boom! Ha!” According to the New York Sun, that cheer “peculiar” to Princeton erupted from its triumphant team after the Yale players’ own gracious cheer in tribute to their collegiate foes after having been subjected to the first nohitter in the history of organized ball. It’s not clear, however, whether any East Coast sportswriters at the time or even the ballplayers themselves understood the historical significance of Princeton’s “signal victory.”[fn]“College Men at the Bat,” New York Sun, May 31, 1875, p. 1.[/fn]

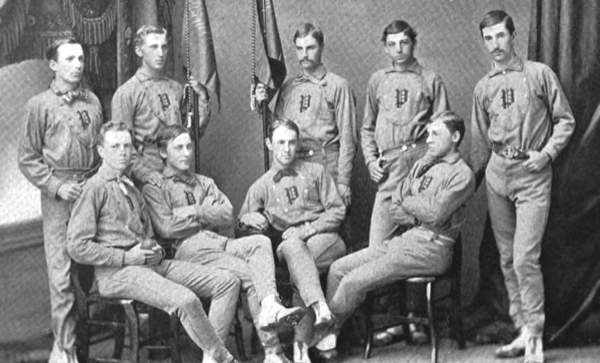

This major milestone was reached on May 29, 1875, by 18-year-old Joe Mann, the pitcher for the visiting Princeton team at Hamilton Park in New Haven, Connecticut. The final score was Princeton 3, Yale 0.

This major milestone was reached on May 29, 1875, by 18-year-old Joe Mann, the pitcher for the visiting Princeton team at Hamilton Park in New Haven, Connecticut. The final score was Princeton 3, Yale 0.

Joseph McElroy Mann was born in New York City on July 13, 1856, to the Rev. Joseph Rich Mann and the former Ellen Thomson. The Rev. Mann graduated from Princeton Seminary in 1848 and for seven years during the 1860s he was pastor of the Second Presbyterian Church in Princeton. One of the Manns’ four other sons was George Williamson Mann, who played on Princeton’s baseball team before young Joe, mostly at shortstop.

Joe Mann appeared in a few Princeton box scores in 1873, though as an infielder. He became the school’s regular pitcher in 1874, and it was actually his work before the no-hitter that garnered much of the fame he experienced later in life. That’s because, later in the century, many sources gave Mann considerable credit for popularizing the curveball, with some even suggesting that he developed the pitch of his own accord.[fn]For example, three letters to the editor on the subject, including one from Mann himself, appeared in the New York Times on June 10, 1900, with a late rebuttal appearing on September 29.[/fn] By late May of 1875, Mann’s teammates had already been exposed to his ability to dominate an opposing nine.

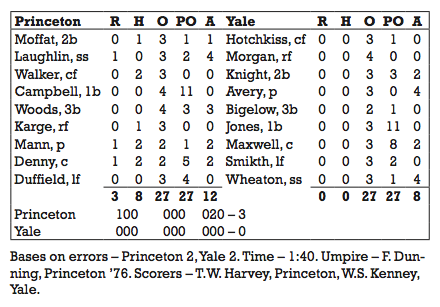

According to the New York Times, a Mr. Rogers of Staten Island was supposed to serve as umpire for the game in New Haven but failed to appear, so Frank Dunning of Princeton was selected. The paper characterized the crowd as “large” and said the defensive highlights “were two flying balls (caught) by Duffield, of the Princetons, in the fourth inning, and corresponding foul catches by Woods.”[fn]“Base-Ball,” New York Times, May 30, 1875.[/fn] A 1901 book, Athletics at Princeton, echoed praise for Duffield’s running catches in left, adding that Moffat did likewise at second base. Denny, as Mann’s catcher, was among those players mentioned as having played faultlessly. However, errors in the first and second innings kept Mann from a perfect game.[fn]Presbrey, Frank and Moffatt, James Hugh. Athletics at Princeton: A History (New York: Frank Presbrey Company, 1901), p. 103.[/fn] According to a much later New York Times account, Yale’s runners both reached base “through a battery error,”[fn]“Distinguished Pitchers,” New York Times, July 29, 1915.[/fn] so if Denny played flawless defense, the errors were Mann’s.

As historic as it was, few other remarkable details of the game were provided. This wasn’t even a case of a pitcher whose dominance manifested itself in a gaudy number of strikeouts, though one of the few sources, besides box scores, for a full picture of how Yale’s batters were retired, was a letter to the New York Times in 1900 by a classmate of Mann’s. Though the writer heaped praise on Princeton’s pitcher, he wrote that “Mann struck out only one Yale man, five Yale men went out on foul flies, two on foul bounds (then allowed), and eight on fair flies, four of which were hit to left field, as the result of the out-curve. The other men went out on in-field plays. …”[fn]W.J. Henderson, an 1876 Princeton graduate, wrote one of the letters to the New York Times that appeared on June 10, 1900.[/fn]

Yale apparently didn’t grouse about the umpiring, but one rationalization surfaced quickly: that Yale’s batters “were caught napping by the use of a Reach ball, which is a little smaller than the regulation size.”[fn]New Haven Palladium, May 31, 1875.[/fn] Did Yale choose that ball, or did the home team not provide one? Regardless, later research suggested that Reach was one of two models of ball accepted as regulation in 1875, the other being Peck and Snyder’s Dead Red. Those two balls were required to have the same weight and dimensions. [fn]Grayson, Harry. “Curve Developed 73 Years Ago.” Portsmouth Herald(NH), May 19, 1948, p. 10.[/fn]

Neither Princeton nor Yale had a campus newspaper until 1876 and 1878, respectively, but fans of baseball in New York were able to read about Yale’s defeat in the Times and the New York Herald a day or two after it happened. However, neither paper noted that Yale had been held hitless. The detailed box score in the Herald included a column for base hits, but its brief article on the game made no mention of Yale’s total hits.[fn]“The National Game,” New York Herald, May 30, 1875, p. 12.[/fn]

It took quite a while for the significance of a nohitter to sink in, much less that Mann’s was a historic first. Still, in the wake of Mann’s dominant performance, some big-time ballplayers, namely John Radcliffe, Bill Boyd, Chick Fulmer, Billy Barnie and Bob Ferguson, reportedly made a point to observe and study Mann at work, if not insist on batting against him.[fn]In fact, on August 8, 1898, the New York Times said that Mann struck out the first four of these. It was Henderson (see note 6) who listed Ferguson, along with the other four, in his letter to the Times in mid-1900.[/fn] Sadly, by the time Mann graduated in 1876 he had pretty much blown out his arm. In fact, according to one of Mann’s two sons, he overextended himself demonstrating his pitching for those professionals.[fn]Grayson, Portsmouth Herald, May 19, 1948.[/fn]

After graduating, Mann worked for the New York World until 1883, then spent three years with the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions before working more than three decades for the publisher Charles Scribner’s Sons in New York. In 1883 he married Fannie Benedict Carter, and they had two sons, both of whom went on to graduate from Princeton and practice law.

Mann died on November 17, 1919, about two years after his wife. In the two decades before his death he was able to enjoy some overdue fame. He loomed large throughout Athletics at Princeton in 1901 (the primary source of the box score)[fn]Presbrey and Moffatt. Athletics at Princeton: A History, especially p. 29-32, 83-84, and 94-108.[/fn] and in 1908 he was one of the two featured speakers at an alumni association event honoring that spring’s baseball team.[fn]“Smoker for Baseball Men,” The Daily Princetonian, October 15, 1908, p. 1.[/fn]Recognition beyond Princeton included being the tenth person featured in a series that ran in the Pittsburgh Press in 1911 under the banner, “Notable Figures in Baseball”[fn]Aulick, W.W. “Notable Figures in Baseball,” Pittsburgh Press, January 13, 1911, p. 26.[/fn] and being featured in a quarter-page article in Sporting Life in 1916. The latter concluded with the author expressing pleasure to note that Mann still played baseball with his two boys, and at some point had regained the ability to pitch fastballs and curves.[fn]Davis, Parke H. “Mann First Curve Pitcher,” Sporting Life, April 22, 1916, p. 6.[/fn]

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Additional Stats

Princeton Tigers 3

Yale Bulldogs 0

At Hamilton Park

New Haven, CT

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.