April 16, 1946: The ‘wearing of the green’ at Braves’ Opening Day

Boston’s baseball fans eagerly awaited the start of the 1946 baseball season. Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey had assembled a formidable post-World War II ballclub that many viewed as having a legitimate shot at the American League crown for the first time since 1918. Further down the road from Yawkey’s Kenmore Square playground, Boston’s Braves had been very active during the Hot Stove season. The ownership triumvirate, dubbed by Hub sportswriters as the Three Little Steam Shovels, had sought to improve Boston’s longstanding National League representative by bolstering its roster and enhancing its home diamond. Through their actions, owners Lou Perini, Guido Rugo, and Joe Maney looked to transform the Braves from a perennial senior circuit second-division dweller into a pennant contender.

Boston’s baseball fans eagerly awaited the start of the 1946 baseball season. Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey had assembled a formidable post-World War II ballclub that many viewed as having a legitimate shot at the American League crown for the first time since 1918. Further down the road from Yawkey’s Kenmore Square playground, Boston’s Braves had been very active during the Hot Stove season. The ownership triumvirate, dubbed by Hub sportswriters as the Three Little Steam Shovels, had sought to improve Boston’s longstanding National League representative by bolstering its roster and enhancing its home diamond. Through their actions, owners Lou Perini, Guido Rugo, and Joe Maney looked to transform the Braves from a perennial senior circuit second-division dweller into a pennant contender.

The Tribe’s owners dug deep into a replenished treasury to lure manager Billy Southworth away from the Cardinals. “Billy the Kid” had skippered St. Louis to three consecutive NL pennants from 1942 through 1944 and claimed world championships in 1942 and 1944. It took a then unheard-of rich multiyear contract offer to induce the former 1921-23 Braves outfielder back to Boston. St. Louis owner Sam Breadon was unable to match the Braves’ overture and reluctantly parted company with his skipper. The Cardinals proprietor’s pockets weren’t deep enough to meet Boston’s contract offer of a reported base salary of $35,000 a season with incentive bonuses for placing fourth ($5,000), third ($10,000), second ($15,000), and first ($20,000). The princely sum of Southworth’s guaranteed annual stipend was akin to $406,000 in 2014.

The Braves’ ownership wasn’t through raiding the Redbirds. In 1945 they had picked up three-time 20-game winner Mort Cooper for a token player and $60,000 and were now flashing a blank check in front of Breadon for Marty Marion, Whitey Kurowski, and Stan Musial. While the latter offers were wisely turned down, the Cardinals did ship outfielder-first baseman Johnny Hopp and first baseman Ray Sanders to the Hub in preseason deals. In return, the Braves sent $40,000 and $25,000 respectively to St. Louis. At Southworth’s behest, other players with Cardinals connections would populate the roster over time to the extent that some Boston sportswriters began to refer to the Braves as the Cape Cod Cardinals.

In addition to roster upgrades, Tribe ownership invested $500,000 in undertaking significant offseason renovations to Braves Field. Just as the club had been the first Boston team to offer Sunday baseball, the Braves would initiate night baseball in the Hub in 1946. Eight light towers were positioned around the Wigwam’s perimeter and new night-only uniforms, using a reflective satin material, were designed. The club introduced the now classic tomahawk-style jersey to both their evening- and day-game togs. A new outfield fence was constructed and shrubbery gardens were planted in the rear of the right-field pavilion and along the streetcar tracks inside the ballpark’s confines.

All this activity was devised to lure fans into Braves Field’s seats. The previous season witnessed a sizable increase in attendance, with the addition of more than 165,000 individuals passing through the park’s turnstiles over 1944 figures. Still, the sixth-place Tribe drew only a bit more than 374,000 fans in 1945. In contrast, the neighboring Red Sox, a seventh-place finisher in the Junior Circuit, attracted over 603,000 to Fenway Park.

Upon their return north from Grapefruit League play, the Braves and Red Sox concluded the preseason exhibition schedule with their annual City Championship Series. In 1946 the competition for Boston baseball supremacy was held at Fenway Park on April 12-14. Boston’s American League representatives handily took two of the three contests. The final game provided Boston’s baseball fandom with an early example of the potency of the Sox’ ’46 lineup. The Crimson Hose humiliated the Tribe, 19-5, before the largest crowd in the history of this event, a paid attendance of 33,279.

In anticipation of commencing the 1946 championship campaign against Leo Durocher’s Brooklyn Dodgers on Tuesday, April 16, workers performed a variety of pre-Opening Day housekeeping tasks at the Wigwam. Among their chores was putting a fresh coat of green paint on the field’s 31-year-old wooden reserved-grandstand seats. The Home of the Braves, built by previous owner James E. Gaffney, stood at the ready to welcome the Tribe’s followers to the dawning of a hoped-for new era of National League baseball in Boston.

Despite all of the offseason hoopla and perhaps as the result of the Braves’ drubbing in the City Series, a disappointing crowd of 19,482 passed through Braves Field’s portals on Opening Day. Those in attendance saw Johnny Sain outduel Brooklyn’s Hal Gregg and deliver a 5-3 complete-game triumph. Billy Herman led the visitors’ attack with four hits in his five at-bats and accounted for two of his team’s tallies. (Herman later would join the Tribe in a June 15 swap.) The Braves and Dodgers were tied at 3-3 through the fifth inning. The lead was captured in the bottom of the sixth when Braves second baseman Connie Ryan scored an unearned run when right fielder Gene Hermanski’s muffed a Tommy Holmes fly ball. An insurance run was plated the next inning on another unearned run occasioned by a Pee Wee Reese error.

The ballplayers’ on-field performance was overshadowed by an unfortunate happening in the stands that is remembered to this day. As was the custom at season starts of yore, those in attendance often dressed up for the occasion and came attired in business suits and other noncasual wear. Early-spring weather in Boston is always unpredictable and, in 1946, had proved less than conducive for the prompt drying of the emerald paint that recently had been applied to ballpark’s grandstand seating. Initially, upon discovering the stains, many irate Braves Field Opening Day patrons marched to the team’s administration building at the park’s main entrance to complain. Overwhelmed staff quickly ran out of cleaning fluid, forcing those affected to leave the ballpark with an unintended green paint souvenir spotting their suits, fur coats, and stockings.

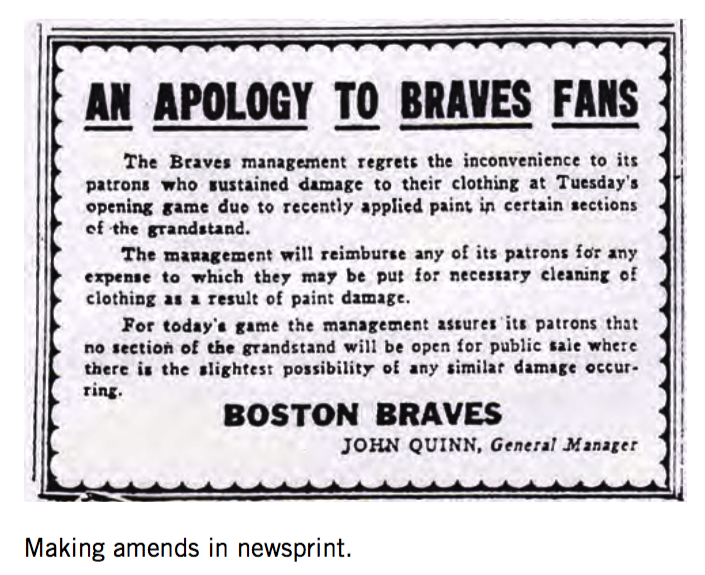

The Braves front office reacted quickly to the first-game fiasco. An advertisement was placed in local newspapers the next day with the heading, “An Apology to Braves Fans.” In print, the club promised full reimbursement of cleaning costs to all of those in attendance suffering from stained clothing. Fans were reassured that those sections of the grandstand with undried paint would be closed off for the season’s second game. Wednesday’s contest drew a little over 11,000 to the Wigwam and while no further incidents were reported, those hearty souls witnessed the Tribe’s first loss of the campaign. The team then boarded a train to Philadelphia for its initial road trip, which would keep it away from Boston until April 28. The Braves secured the loan of Fenway Park from Tom Yawkey for a brief return to the Hub for a Sunday doubleheader against the Philadelphia Phillies. Emerging victorious in both games of the twin bill, they left town until May 11, allowing ample time to cure the sticky chairs in the Wigwam’s reserved grandstand. The Braves wisely waited until the club went on the road after the season’s second homestand to complete their internal painting project. All other reserved seats received a maroon coating, while box seats were adorned in gold.

True to their promise, the Braves opened up a “paint account” at a local bank to house funds to reimburse those with damaged clothing. Two attorneys were retained to review claims for compensation. As a result of the incident’s drawing national media attention, some dubious demands began to flow into Braves headquarters as evidenced by claims emanating from such faraway places as Florida, California, and Nebraska. All told, about 13,000 requests (representing approximately 67 percent of the day’s official attendance) were received. The letters were processed over the summer months and the ballclub intentionally applied a fairly liberal standard in determining the legitimacy of the petitions. More than 5,000 claims were accepted with payouts averaging $1.50 and ranging as high as $50. Even though the blunder ended up costing the Braves around $6,000, the astute manner by which they addressed it brought about favorable free publicity and generated goodwill that aided an upsurge of attendance at the Wigwam. Despite the inauspicious start to the 1946 season, attendance at Braves Field increased to a club record of 969,673.

This article appeared in “Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

Box scores for this game can be found on baseball-reference.com, and retrosheet.org at:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BSN/BSN194604160.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1946/B04160BSN1946.htm

The author reviewed contemporary newspaper accounts as well as The Sporting News; Retrosheet; Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves: 1871-1953; and materials in the archives of the Boston Braves Historical Association.

Additional Stats

Boston Braves 5

Brooklyn Dodgers 3

Braves Field

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.