The American League’s First Baltimore Orioles: John McGraw, Wilbert Robinson, and Rivalries Created

This article was written by Gordon J. Gattie

This article was published in The National Pastime: A Bird’s-Eye View of Baltimore (2020)

Professional baseball’s first Baltimore Orioles played in the American Association (AA) in 1882. Another franchise of the same name played in the AA from 1883 until joining the National League (NL) for nine seasons, from 1891 through 1899, but the NL vacated four cities after the 1899 season. The following season, the Western League’s owners changed the name of their organization to the American League and sought to establish the AL as a rival major league to the NL. They seized the opportunity to replace former NL franchises with AL teams in Baltimore, Washington, and Cleveland.1 The American League’s Baltimore Orioles was created as a member of the junior circuit on January 4, 1901.

Professional baseball’s first Baltimore Orioles played in the American Association (AA) in 1882. Another franchise of the same name played in the AA from 1883 until joining the National League (NL) for nine seasons, from 1891 through 1899, but the NL vacated four cities after the 1899 season. The following season, the Western League’s owners changed the name of their organization to the American League and sought to establish the AL as a rival major league to the NL. They seized the opportunity to replace former NL franchises with AL teams in Baltimore, Washington, and Cleveland.1 The American League’s Baltimore Orioles was created as a member of the junior circuit on January 4, 1901.

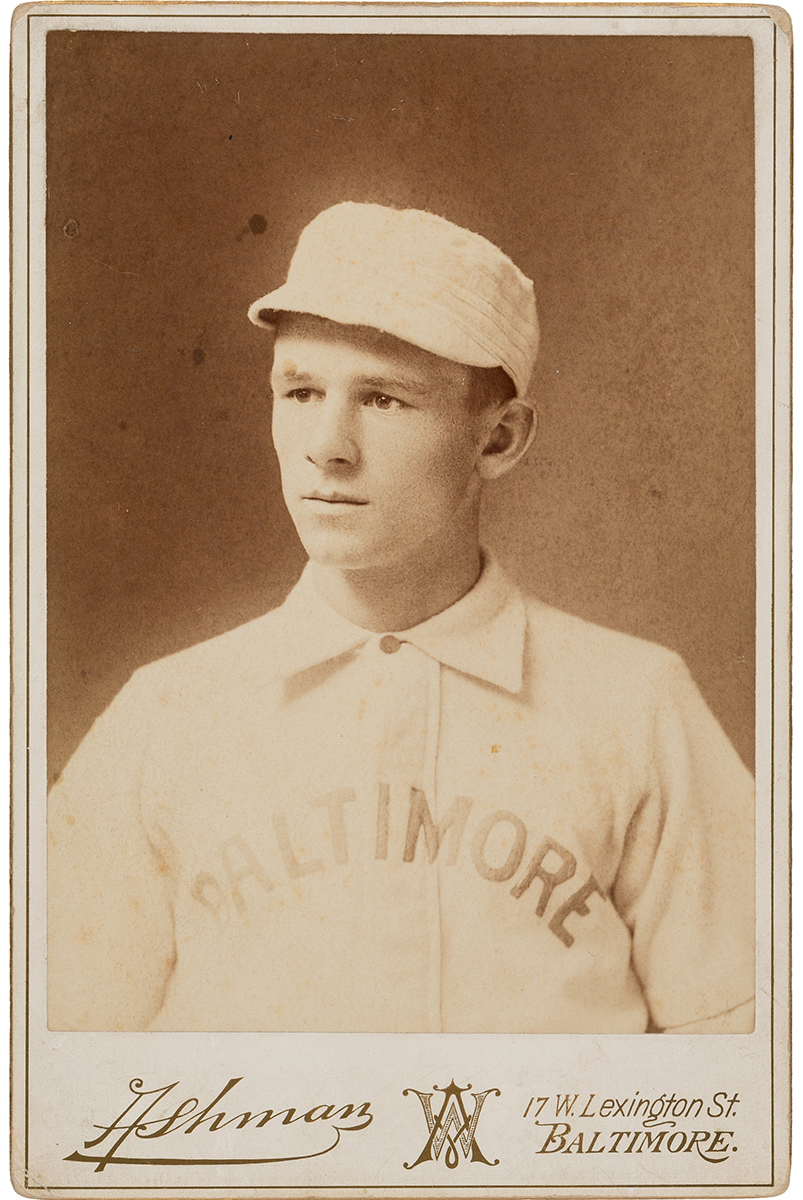

Although Johnson desperately wanted a franchise in New York City, the politically powerful New York Giants successfully prevented the AL from moving there. Instead, Johnson placed a team in Baltimore and recruited John McGraw to lead the new franchise. The ballclub was incorporated as the “Baltimore Baseball and Athletic Company” and originally issued 400 shares of stock valued at $100 apiece. The initial incorporators included players McGraw and Robinson, Justice Harry Goldman, Eutaw House proprietor Col. James P. Shannon, St. Vincent’s Catholic Church pastor Reverend John D. Boland, city tax judge Conway W. Sams, and Baltimore businessmen S. Miles Brinkley and Moses N. Frank.2

Baltimore fans waited out two consecutive rainouts before celebrating Opening Day on April 26, 1901. The afternoon festivities included a procession of nearly 50 carriages from the Eutaw House Hotel to American League Park and pregame activities included Johnson throwing the ceremonial first pitch.3 The Orioles won their inaugural game over the Boston Americans in front of over 10,000 fans, 10-6, led by Mike Donlin’s two triples and Joe McGinnity’s complete game.4 The Orioles occupied second place during mid-May, then slumped to fourth place following a four-game losing streak.

The team endured a challenging early June. After winning their first two games that month, the Orioles lost eight of their next ten contests. They fell to sixth place and 7½ games behind the league-leading Chicago White Sox following a 7–6 loss to the Milwaukee Brewers. The Orioles had built a 6–1 lead after six innings and outhit Milwaukee 15-13, but the Brewers scored six unanswered runs, winning the 10-inning contest on a sacrifice fly following an errant throw. Frustrated with the team’s ability to lose ballgames apparently within their grasp, one newspaper reporter noted, “If the defeats in themselves are becoming somewhat monotonous, the Orioles manage to have a charming variety in the methods by which they lose.”5

Throughout the season, McGraw attempted to improve his team by recruiting players from other teams, including NL ballclubs. One of McGraw’s top targets was his previous teammate and future Hall of Fame shortstop Hughie Jennings. Jennings was traded from Louisville to Baltimore in 1893 and played with the NL Orioles through the 1898 season, where he became the NL’s top shortstop. Throughout June, four different ballclubs sought Jennings’ services, including Baltimore, the AL Philadelphia Athletics, and the NL Philadelphia Phillies.6

Although McGraw stated Jennings would play in Baltimore, President Johnson overrode McGraw and recognized the Athletics’ claim, stating “Law and order must prevail in the American League, and the Baltimore club will not be allowed to have its own way any more than any other club. McGraw hasn’t a leg to stand upon in this matter, and if he drives Jennings into the National League the Athletic club deserves some redress for which Baltimore should be held responsible.”7

McGraw rebutted Johnson’s remarks, claiming Jennings hadn’t been claimed when negotiations occurred, and that Johnson interfered because of his friendly relationship with Athletics’ owner Connie Mack. Jennings ultimately played for neither the Orioles nor the Athletics, opting for the Phillies instead. The dispute over Jennings foreshadowed future McGraw-Johnson tussles.

The next day Baltimore defeated Milwaukee 11-4, the first of 11 consecutive wins, their longest winning streak that season. Their victories included sweeps of Detroit and Philadelphia and moved the Orioles into third place. Unfortunately, injuries to McGraw, Robinson, and other key players, along with frequent umpire troubles, led to a late season swoon and eventual fifth-place finish.8 The Orioles struggled during early September, compiling a 4-19-2 record from August 27 through September 18, then finished the season on a high note, winning eight straight before losing the season finale; after their eighth-straight win, one reporter observed, “There was nothing sensational about the game, but throughout there was the pleasant feeling of hopeful confidence.”9 Their late September streak pushed Baltimore back over the .500 mark, widening the gap between them and the sixth-place Washington Senators.

Based on their early season success, fans “confidently expected that by this time they would certainly be running neck and neck for second place and more probably fighting desperately for first.”10 The Orioles ultimately compiled a 68-65 record, 13½ games behind the pennant-winning Chicago White Sox. The Orioles led the AL with a .294 team batting average and a .353 team on-base average, while finishing third with 761 runs and 1,348 hits. McGraw, who managed and played third base before a mid-season injury, led the team with a .349 batting average and .995 OPS while pacing the AL with 14 hit-by-pitches in only 308 plate appearances; outfielder Mike Donlin led the full-season regulars with a .340 batting average and .883 OPS. Second baseman Jimmy Williams and shortstop Bill Keister each hit 21 triples and drove in over 90 runs. Baltimore’s pitching staff, which had the highest average age in the league (29.0 years), attained a fourth-best 3.73 ERA, collectively struck out a league-low 271 opponents, and issued a near-league average 344 walks. Joe McGinnity, returning to Baltimore and among those jumping from the NL to the AL, led Orioles hurlers with a 3.56 ERA, 26 wins, and 382 innings. The American League thrived during its first year as a self-proclaimed major league, and only one franchise changed locations during the off-season. (The Milwaukee Brewers moved to St. Louis and were renamed the Browns.)

The Orioles started 1902 on the right foot. On January 1, Baltimore announced they signed Joe McGinnity to a three-year deal. McGinnity had been pursued by the NL’s Brooklyn Superbas; he had been assigned to Brooklyn before the 1900 season, then jumped to Baltimore before the 1901 season. As the season approached, McGraw set his everyday lineup with shortstop Billy Gilbert leading off, followed by outfielder Jimmy Sheckard, third baseman Joe Kelley, outfielder Cy Seymour, second baseman Jimmy Williams, outfielder Kip Selbach, first baseman Dan McGann, the catcher, and the pitcher.11 The Orioles’ roster experienced significant turnover during the season; only Harry Howell, Wilbert Robinson, Gilbert, Seymour, Selbach, and Williams played in at least half of Baltimore’s 138 games.

Similar to their inaugural season, the Orioles planned a gala parade for Opening Day 1902. On April 23, the procession would leave the Eutaw House and travel throughout the city to the ballgrounds. There were plans for “12 mounted patrolmen and Packard’s Band of 30 pieces” as well. However, unlike the previous season, no complimentary tickets were issued for Opening Day.12 Due to a last-minute scheduling change, the Orioles opened their 1902 campaign in Boston before returning to Baltimore and hosting the Athletics for the home opener. On April 19, Baltimore carried a 6-3 lead heading into the ninth inning, scoring insurance runs during the eighth and ninth frames. Unfortunately for the Orioles, a late Boston rally resulted in four answered runs as Baltimore dropped the season opener.13 They didn’t fare better in their home opener, losing to Philadelphia, 8-1, though over 10,000 fans attended the ballgame.14

Baltimore endured a challenging season. Although the Orioles won four of their next six contests, they lost their next five games and slipped to seventh place. The team struggled and McGraw argued with Johnson and AL umpires while the wheels were set in motion for his eventual jump to the New York Giants. After May 2, the Orioles’ highest placement for the season was fourth place; their last day in the league’s upper division was June 14. However, there were reasons for hope throughout the season’s first half. On May 9, McGraw returned from a five-game suspension, and the Orioles “played like a new team” as they defeated Philadelphia, 13-6, to end their five-game losing streak and knock the Athletics from the AL’s top spot. The ballclub was praised for resurrecting the hit-and-run, Gilbert’s excellent fielding was commended, and Williams homered.15 On May 30, the Orioles swept a doubleheader from Cleveland, winning by scores of 10-7 and 12-4. The opening line from the Baltimore Sun’s game recap read: “It was a great day for Baltimore — a great day.”16

Baltimore split the next four games; the last time the Orioles had a .500 or better winning percentage was on June 4. Their season started spiraling downward in late June and reached a low point on July 17, when they were forced to forfeit a game against the St. Louis Browns, the day after McGraw joined the New York Giants as manager. A few weeks earlier, on June 30, Johnson had suspended McGraw and Joseph Kelley indefinitely for their actions during the previous Saturday’s ballgame against Boston. Johnson commented on McGraw’s actions, “I have had time enough since I returned from the North to make a thorough investigation of this Baltimore trouble, and I am convinced that Umpire Connolly was absolutely right.”17 Robinson was named manager in McGraw’s absence. Infuriated with his continued treatment by Johnson, McGraw left the AL for the Giants, where he would manage for 31 seasons and win over 2500 ballgames.

In addition to securing McGraw, the Giants signed McGinnity, Cronin, Bresnahan, and McGann to contracts — and Kelley and Seymour jumped to Cincinnati — leaving the Orioles without enough players to field a team.18 Johnson pieced together a roster with players from other AL clubs — and the old Baltimore NL club19 — so the Orioles could finish the season. The Orioles stumbled to the finish line, compiling an 8-20 record in August and 5-23 record in September, which included an 11-game losing streak.

Baltimore finished last at 50-88, 34 games behind the pennant-winning Philadelphia Athletics. Outfielder Kip Selbach, one of only three Orioles to play at least 100 games that season, lead the team in most offensive categories: plate appearances (573), runs (86), hits (161), and batting average (.320), with second baseman Jimmy Williams tallying the most triples (21), home runs (8), and best OPS (.861) on the team. McGinnity, despite leaving for New York in July, still led Baltimore hurlers with 13 wins and a 3.44 ERA, and finished second with 198⅔ innings pitched, just behind Harry Howell’s 199 innings.

President Johnson successfully moved the AL Orioles’ franchise from Baltimore to New York for the 1903 season.20 In March, the American League’s New York franchise was approved and commenced operations, incorporated as the Greater New York Baseball Association.21 The rebranded New York Americans, variously nicknamed “Hilltoppers” and “Highlanders” in the press for the playing field located on elevated terrain, and “Yankees” possibly tongue-in-cheek because the ballpark was slightly north of the Giants’, would use “Yankees” as the team’s primary nickname starting in 1913.22 The AL would not return to Baltimore for over fifty years, until the 1954 season when the St. Louis Browns moved east and became the second AL incarnation of the Orioles.

Though the franchise shifted from Baltimore to New York, the statistics associated with the 1901–02 Baltimore Orioles have been relegated to those of a defunct organization. The New York Yankees don’t recognize the Baltimore Orioles in their official team records. Baseball-Reference.com published an article on the debate in 2014.23 The current Baltimore Orioles trace their history from the AL charter member Milwaukee Brewers, through the St. Louis Browns and the 1953 season, to Baltimore in time for the 1954 campaign.

The 1901–02 Baltimore Orioles left a notable mark on baseball history during their short existence. Baltimore compiled a 118-153 record over their two seasons. The Orioles had only two managers in its history: Hall of Famers McGraw and Robinson, who both later managed New York-based NL teams (Robinson joining Brooklyn, where he would manage 1914-31). Their biggest hitting and pitching stars — Jimmy Williams was their best offensive player, while Joe McGinnity more firmly established his status as a top-tier major league pitcher–would shine in New York over the next five years for the Yankees and Giants, respectively. Bitterness lingered between Johnson and McGraw; the 1904 World Series wasn’t played in large part because McGraw didn’t want his Giants to play the AL pennant winner, spiting Johnson and his attempts to establish the AL’s status as equal to the NL.

These early Baltimore Orioles should be remembered as having a key location for a major league franchise, serving a critical role in the evolution of the AL-NL relationship, and the lasting impact on New York baseball, between McGraw’s tenure with the Giants, Robinson’s years with the Robins (later Dodgers), and the franchise’s rebirth as the New York Yankees.

GORDON J. GATTIE is an engineer for the US Navy. His baseball research interests include ballparks, historical trends, and statistical analysis. A SABR member since 1998, Gordon earned his PhD from SUNY Buffalo, where he used baseball to investigate judgment performance in complex dynamic environments. Ever the optimist, he dreams of a Cleveland Indians-Washington Nationals World Series matchup, especially after the Nationals’ 2019 World Series championship. Lisa, his wonderful wife who roots for the Yankees, and Morrigan, their beloved Labrador Retriever, are looking forward to resuming their cross-country travels visiting ballparks and other baseball-related sites. Gordon has contributed to several SABR publications, including The National Pastime and the Games Project.

Additional Sources

Kavanagh, Jack, and Norman Macht, Uncle Robbie (Cleveland, OH: Society for American Baseball Research, 1999): 11-47.

Koppett, Leonard, The Man in the Dugout (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1993): 30-67.

Levitt, Daniel R., The Battle that Forged Modern Baseball: The Federal League Challenge and Its Legacy (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee Publishers, 2012).

Retrosheet: http://www.retrosheet.org/

Thorn, John (2012). The House That McGraw Built. On “Our Game” blog, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/the-house-that-mcgraw-built-2bf6f75aa8dc.

Notes

1 Joe Santry and Cindy Thompson, “Byron Bancroft Johnson,” In David Jones (Ed.), Deadball Stars of the American League (Dulles, VA: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006), 390-392.

2 “Ball Club Incorporation: Baltimore’s American League Team With $40,000 Of Stock,” Baltimore Sun, January 5, 1901, 6.

3 Jimmy Keenan, “April 26, 1901: Baltimore Orioles Win Home Opener in a New Major League,” SABR Games Project, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/april-26-1901-baltimore-orioles-win-home-opener-new-major-league. Accessed December 1, 2019.

4 “’Rah For Baseball,” Baltimore Sun, April 27, 1901, 6.

5 “Orioles Ten Inning Defeat,” Baltimore Sun, June 18, 1901, 6.

6 C. Paul Rodgers III, “Hugh Ambrose Jennings,” in David Jones (Ed.), Deadball Stars of the American League (Dulles, VA: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006), 555-558.

7 “Hot Baseball Row,” Baltimore Sun, June 18, 1901, 6.

8 Francis Richter (Ed.) Reach’s Official American League Base Ball Guide for 1902 (Philadelphia: A.J. Reach, 1902), 56.

9 “Can’t Stop Winning,” Baltimore Sun, September 28, 1901, 6.

10 “Baseball Ends Today,” Baltimore Sun, September 28, 1901, 6.

11 Frank F. Patterson, “Is Ready to Play,” The Sporting News, April 19, 1902, 3.

12 “Orioles’ Opening Program,” Baltimore Sun, April 19, 1902, 6.

13 “Orioles Lose First,” Baltimore Sun, April 20, 1902, 6.

14 “Athletics Play Havoc With Manager McGraw’s Pet Birds,” The Washington Times, April 24, 1902, 4.

15 “Win a Game At Last,” Baltimore Sun, May 10, 1902, 6.

16 “’Twas a Great Day,” Baltimore Sun, May 31, 1902, 6.

17 “Ban Suspends Again,” Baltimore Sun, July 1, 1902, 6.

18 “Giants Strengthened By Sensational Deal,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 17, 1902, 11.

19 “Here’s the New Team,” Baltimore Sun, July 18, 1902, 6.

20 John Thorn, Pete Palmer, and Michael Gershman (Eds.) Total Baseball: The Official Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball (4th Edition) New York: Viking Press, 1995), 43.

21 Mark Armour and Daniel R. Levitt, “New York Yankees Team Ownership History,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/topic/new-york-yankees-team-ownership-history/. Accessed July 7, 2020.

22 New York Yankees, History of the New York Yankees, 2018 New York Yankees Official Media Guide and Record Book, 244.

23 Mike Lynch, “1901-02 Orioles Removed from Yankees History,” On “Sports Reference Blog, https://www.sports-reference.com/blog/2014/07/1901-02-orioles-removed-from-yankees-history/. Accessed December 1, 2019.