Major League Player Ethnicity, Participation, and Fielding Position, 1946-2018

This article was written by Charlie Pavitt

This article was published in Fall 2020 Baseball Research Journal

This is a study of the relationship between major league player ethnicity and both overall participation and fielding position — from 1947, Jackie Robinson’s debut year, to 2018.1 I use the term “ethnicity” as an umbrella term encompassing the concept of “race” because the presence of Hispanics as a separate grouping invalidates a simple racial distinction. This is not the forum for a discussion as to whether race is a biological fact or a cultural concept only. In either case, players perceived as “colored,” or whatever term was then in fashion, were barred from major league baseball from the 1890s until 1947; Hispanics were only allowed in if, through accident of birth, they were accepted as “white.”

This is a study of the relationship between major league player ethnicity and both overall participation and fielding position — from 1947, Jackie Robinson’s debut year, to 2018.1 I use the term “ethnicity” as an umbrella term encompassing the concept of “race” because the presence of Hispanics as a separate grouping invalidates a simple racial distinction. This is not the forum for a discussion as to whether race is a biological fact or a cultural concept only. In either case, players perceived as “colored,” or whatever term was then in fashion, were barred from major league baseball from the 1890s until 1947; Hispanics were only allowed in if, through accident of birth, they were accepted as “white.”

Even after Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby, teams differed substantially in their willingness to integrate; it took the Red Sox until 1959, when public pressure resulted in Pumpsie Green’s call-up from the minors, to become the final major league team to integrate. In baseball there are noticeable associations between ethnicity and position, which for want of a better term I will refer to as “positional differentiation.”

Baseball has not been alone among team sports with such correlations. In ice hockey, the significant distinction — at least until the influx of players from other countries — had been between English-Canadians and French-Canadians, with fewer of the former at defense and more at goal, while an argument has been made that Aboriginal Canadians have been stereotyped as “enforcers.”2 In football and basketball, the significant distinctions are between Black and White in American football, Blacks are more prevalent at wide receiver, running back, and defensive back; Whites at quarterback, tight end, and the offensive line.3 In basketball, Blacks were once more likely to be forwards and center and Whites more often at guard relative to their overall proportions, although these tendencies may have diminished over time.4 Alone of the major North American team sports, soccer is overall the most diverse of the five, although there is evidence of a small bias toward Blacks at forward and Whites at other positions in the top four divisions of English soccer.5

Sociologists have been examining positional differentiation in baseball for about half a century. In an excellent review of work up to that time, Curtis and Loy credited Rosenblatt as beginning academic conversation on this topic, the latter author having noted Blacks to have been underrepresented as pitchers and over-represented as outfielders in every season from 1953 through 1965.6,7 Curtis and Loy presented a number of tables summarizing research findings up to that time, including seven previous studies about baseball, encompassing eighteen separate seasons between 1950 and 1975; I am aware of several additional reports since.

The data are clearly in support of the claim that positional differentiation has been rampant in professional baseball. Just choosing one study in the set (the others are substantively the same), Loy and Elvogue examined players from 1956 through 1967 and noted that 19.5 percent of major leaguers over that time were Blacks; during that interim, Blacks totaled 5.6 percent of catchers, 9.3 percent of shortstops, 10.3 percent of second basemen, 18 percent of third basemen, 19.4 percent of first basemen, and 32.1 percent of outfielders.8

Note the similarity between this and both positional centrality (see below) and Bill James’s Defensive Spectrum with third base correctly ordered ahead of center field; the only clear difference is the relative preponderance of Black first basemen. If we can accept Loy and Elvogue’s interesting assumption that catchers should get assists for their pitchers’ strikeouts, it turns out that the rank-ordering of assists per position exactly matched the ranking of Blacks per position just listed.

One problem with some of these studies was the failure to distinguish Hispanics from Black Non-Hispanics and White Non-Hispanics. Loy and Elvogue made the attempt, and although their sample size was too small for clear conclusions, there is a glimpse of the fact that, even then, Hispanics were at least slightly over-represented in the middle infield.9 Pattnayak and Leonard also noticed this trend, as (to her surprise) did Gonzalez, discovering that Hispanics have been over-represented at shortstop since the mid-1950s, at second base since the mid-1960s, and holding their own at catcher.10,11 The inclusion of Hispanics as a separate category is critical for evaluating the proposed explanations for these disparities, as I will below.

The study reported here is based on a data set Pete Palmer sent me, which he put together with help from Stu Shea and Gary Gillette, categorizing players as either White Non-Hispanic, Black Non-Hispanic, Hispanic, or Other, with the latter mostly First Nation at the beginning but now predominately Asian. For classification, Pete, Stu, and Gary used the 1954 Baseball Register (which at the time included very specific ethnicity information), various Internet sources when ethnicity information was available, and made judgments from photographs when not. Their data set includes the number of game appearances as pitchers, catchers, infielders (including first base), and outfielders for every year between 1946 and 2018. The diagrams included herein were based on the annual data, but labels are only provided for each third year to prevent visual clutter.

Ethnicity and Total Participation

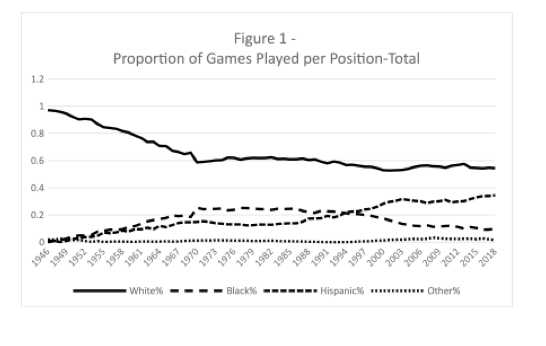

Figure 1 displays the proportion of game appearances for players within the four ethnicities in the 1946-2018 time frame.

Figure 1. Proportion of Games Played Per Position–Total

In 1946, baseball was almost universally White Non-Hispanic, with 1.1 percent Hispanics considered White and 1.9 percent Other. The proportion of White Non-Hispanics drifted down to about 60 percent in 1970 and has been at about 55 percent since around 2000. The now-well-known rise and fall of Black Non-Hispanic major leaguers is evident, reaching the high-water mark of around 25 percent between 1970 and 1985 and dipping to about 10 percent starting in 2013. Hispanics have taken up most of the slack; climbing to and then leveling off at 13-14 percent between 1967 and 1987 but rising over 34 percent on 2018. The contribution of Others has only been above 3 percent only once, in 2008.

In a personal communication, Pete Palmer provided some possible explanations for these patterns with which I agree. For Hispanics, increasing opportunity has led to increased participation, particularly as scouting and player development (for example, the Dominican Summer League) have intensified. For Black Non-Hispanics, the rise was certainly a product of increasing opportunity, with the fall perhaps influenced by the advance of structural racism in inner cities, along with the increasing attraction of football and basketball. An audience member at a presentation of these data at the 2020 annual meeting of the Bob Davids SABR Chapter (Greater Washington, DC) proposed the loss of ballfields in inner cities as another possible causal factor.

Ethnicity and Position

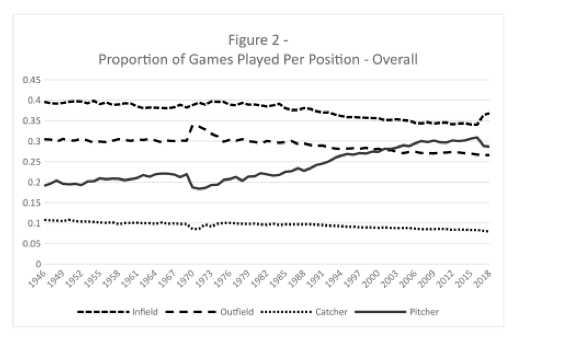

Subsequent diagrams chart the extent of positional differentiation between 1946 and 2018. Figure 2 displays the overall distribution of games played by pitchers, catchers, infielders, and outfielders. Pitchers, although only one of nine positions, has not surprisingly made up a large share of the overall total, and as relievers have become a greater part of the game, this share has increased from about 20 to about 30 percent. In response, the summed four infield positions have dropped from about 40 to 35 percent and three outfield positions from about 30 percent to 26.5. Catching has also declined a tad, from over 10 percent to about 8.

Figure 2. Proportion of Games Played Per Position–Overall

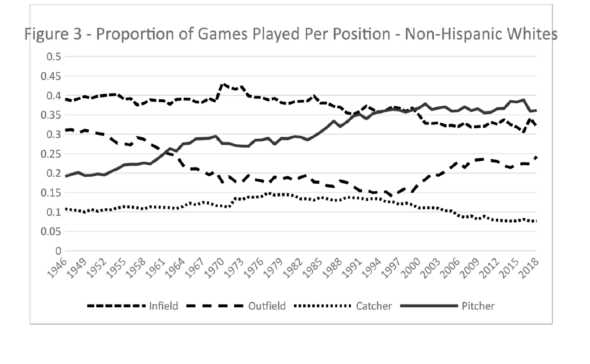

When we classify by ethnicity, the biases become clear. Figure 3 shows proportion of games played per position for White Non-Hispanic Players. As the proportion of other ethnicities entering the major leagues increased during the 1950s and 1960s, the proportion of games for White Non-Hispanic pitchers rose to about 10 percent greater than for pitchers overall, with White Non-Hispanic outfielders falling about the same amount. In the 2000s, the proportion of games for White Non-Hispanic infielders has dipped to noticeably less than the overall proportion.

Figure 3. Proportion of Games Played Per Position–Non-Hispanic Whites

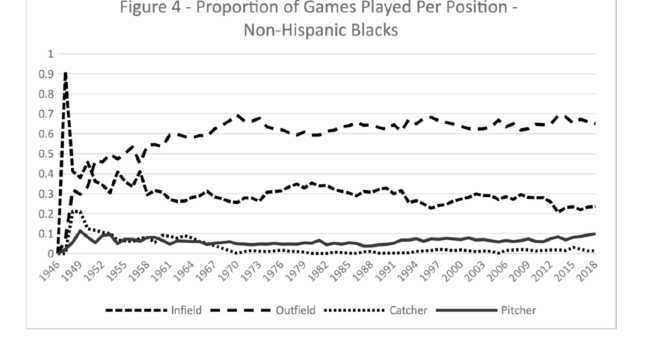

Figure 4 shows the proportion of games played per position for Black Non-Hispanic players. Simply put, Black Non-Hispanics become outfielders, and are considerably less often found at the other positions.

Figure 4. Proportion of Games Played Per Position–Non-Hispanic Blacks

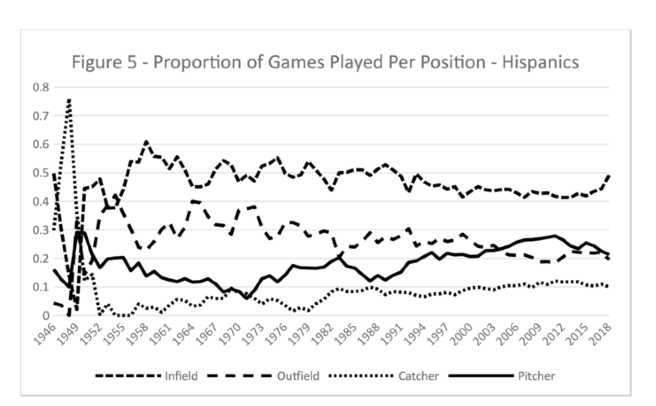

Figure 5 demonstrates proportion of games played per position for Hispanic players. Again simply put, Hispanics become infielders.

Figure 5. Proportion of Games Played Per Position–Hispanics

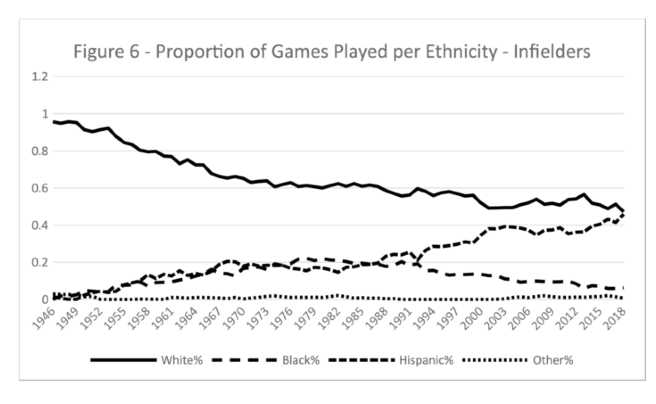

Figure 6 makes that clear. Note how in 2018 there were as many games played by Hispanic infielders as White Non-Hispanic infielders, despite the latter’s greater overall abundance.

Figure 6. Proportion of Games Played Per Ethnicity–Infielders

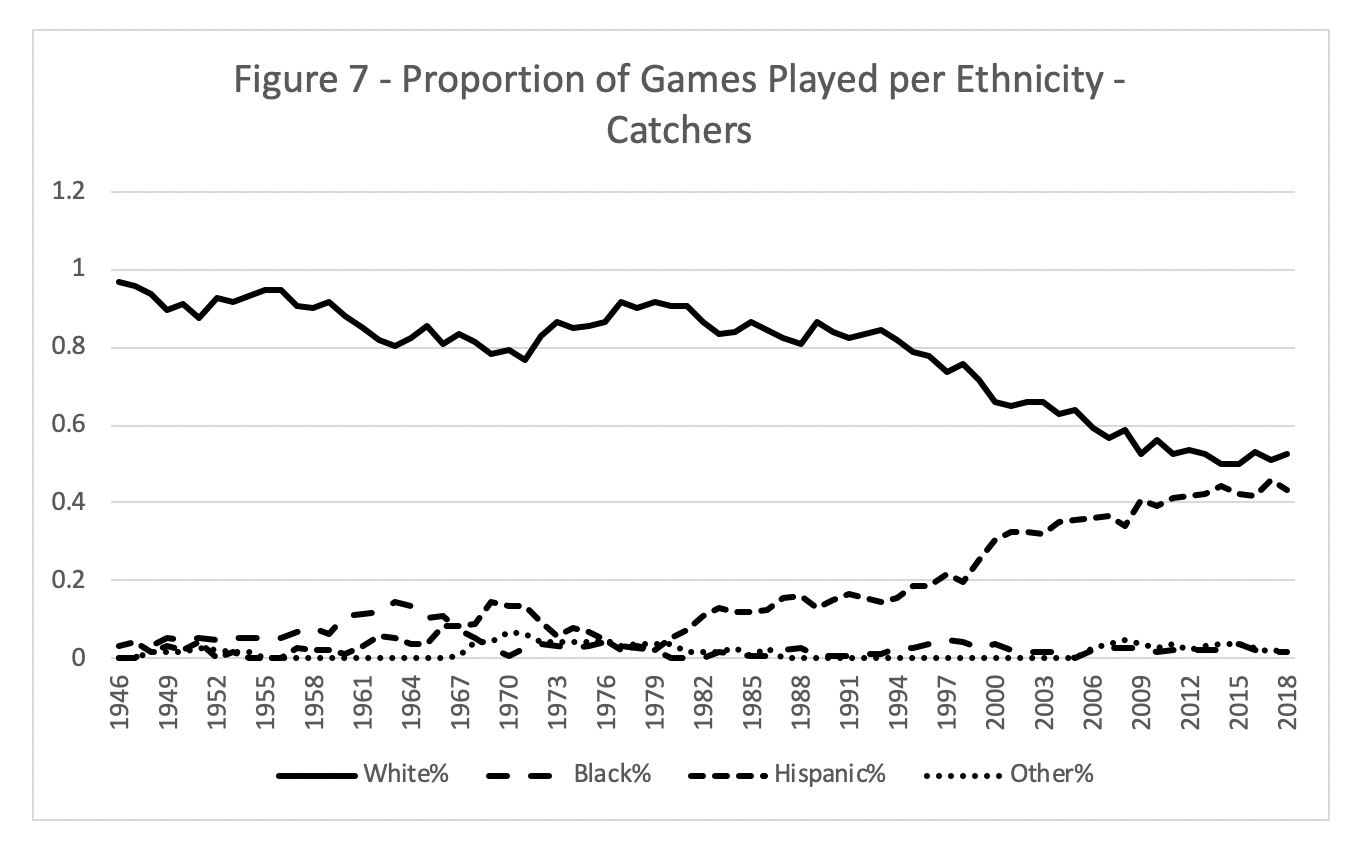

Figure 7 reveals another important trend; Hispanics are more and more becoming evident as catchers; their number of games played has almost caught up to those for White Non-Hispanics. In contrast, there are presently no African-American catchers in the major leagues, a situation that has received recent attention.12

Figure 7. Proportion of Games Played Per Ethnicity–Catchers

There have been, and continue to be, too few Others for the related data on positional differentiation to reveal bias or allow us to draw conclusions.

Explanations

Sociologists have put considerable work into examining positional differentiation under the concept of “stacking.” According to Ball (as cited by Curtis and Loy13), stacking is defined as the “assignment of a playing position, an achieved status, on the basis of an ascribed state,” with race or ethnicity the ascribed state relevant in sports. Note that this definition works under the assumption that positional assignment is based on ethnicity and not some other factor. The implication is that more “valued” ethnicities are more likely to occupy central positions; in baseball, this means the battery and middle infield.

Another contribution of the Curtis and Loy essay is a review of such explanations. Two are based on discrimination. The first is sheer bigotry: based on stereotypes of Blacks as “too dumb” to play a position supposedly requiring smarts, a position argued with no apparent evidence by Smith and Leonard.14 The second somewhat more subtly proposed that central positions require a lot of communication among players, which allegedly becomes problematic between players of different races; if so, then why not have a totally Black battery or infield?

Two additional explanations do not begin with the presumption of discrimination as such. The first is that unlike the outfield, the central positions require more expensive training and equipment that the underclass cannot afford (the “economic” hypothesis, favored by Medoff,15 and by Sack, Singh, and Thiel16). The second would be a case of self-fulfilling prophecy: young Blacks acquired players such as Henry Aaron and Willie Mays as role models, and young Hispanics examples such as Luis Aparicio and more recently Ivan Rodriguez and aspired to emulate them all the way down to position.

Proposals relying on psychological differences have included the idea that Black people are more prone than White people to be attracted to roles in which they can work independently from others, and the notion that Black people are relatively better at reactive tasks (the outfielder reacts to the flight of the ball) and White people at proactive tasks (pitchers and catchers pre-plan their strategy). According to the Curtis and Loy review, both of these ideas have some support among the general population, although the second seems to be at least somewhat contradicted by outfielders positioning themselves before the play and catchers having to respond quickly to whatever occurs as plays unfold.17 One final proposal is that actual physiological differences exist between races such that Black people are better at running and jumping than White people. If there is any evidence of this in the general population, it is irrelevant to the elite grouping from which major leaguers emerge.

Examining just the evidence concerning Black Non-Hispanics versus White Non-Hispanics implies that some sort of racial differentiation is at work. It is hard to evaluate the raw discrimination proposal, although Scully presented some relevant data reprinted from the June 1969 issue of Ebony magazine implying that the darker the skin of the Black player, the more likely that he was an outfielder.18

In an explicit attempt to compare the economic, role model, and either of the discrimination explanations, Guppy looked at ethnic differences in positional changes for players with five years of MLB experience between 1958 and 1973.19 Forty-seven percent of Black Non-Hispanic infielders were in the outfield five years later versus 26 percent of White Non-Hispanic infielders, whereas 16 percent of White Non-Hispanic outfielders were in the infield five years later versus 7 percent of Black Non-Hispanics. Guppy used the fact that there were no differences in batting average, runs scored, and fielding average between first year Black and White infielders to argue that skill differences did not exist, leaving discrimination as the only viable explanation. However, these performance indicators are mostly irrelevant; positional change is mostly a product of defensive skill, and teams back then probably used their informal observations of ability rather than fielding average as the main basis for their decisions.

The issue of defense actually came up in later work by Lavoie and Leonard, based on sociological thinking that discrimination is more likely when there are less certain indicators of performance quality.20 It follows for the authors that stacking would be more likely for positions in which defense (which is harder to measure with certainty) is relatively more important. This is clearly true for Black Non-Hispanics, who have historically been underrepresented at catcher and the middle infield.

At the time of Guppy’s work, there was reason to believe that Hispanics had status intermediate between White Non-Hispanics and Black Non-Hispanics, as 17 percent moved from the infield to the outfield versus 9 percent in the other direction.21 Having noticed this trend, Pattnayak and Leonard made just that hypothesis, and also speculated that they might have more success attaining managerial positions upon retirement than Black Non-Hispanics.22 However, as described above, by the time of Gonzalez’s work, it was evident that Hispanics were very well represented in the middle infield and at catcher.23 This fact certainly contradicts the uncertainty and economic hypotheses, and unless it can be demonstrated that discrimination against Hispanics has decreased over time, spells trouble for proposals relying on it.

Complicating the issue is the work of Margolis and Piliavin, who discovered that, as a group, Black Non-Hispanic players are bigger and Hispanics smaller than White Non-Hispanics.24 This fits with the assignment of the former to the outfield and the latter to the middle infield, but suggests an additional hypothesis: that positional differentiation could be a product of selective opportunities for players based on size-based stereotypes for the three ethnicities.

In support, when combining size with ethnicity in models predicting position centrality, Hispanics were at that time discriminated against in the sense that they were more likely to be assigned non-central positions than White Non-Hispanics of equivalent size. Sack, Singh, and Thiel replicated and extended this discovery, discerning that including indicators of speed (attempted steals) and power (slugging average) decreased although did not eliminate the impact of ethnicity on playing position.25 As Pete Palmer pointed out to me, the problem with this account is that pitchers tend to be as big as or bigger in both height and weight than players at other positions, and so should feature more Black Non-Hispanics if size differences in ethnicities were relevant.

In conclusion, positional differentiation is a real phenomenon. In my opinion, given the available data, the role modeling process is likely the best overall explanation for positional differentiation, although racism cannot be ruled out, especially in the case of Black Non-Hispanics being stereotyped as less capable of playing the most central positions.26

CHARLIE PAVITT has been a SABR member since 1983 and contributing to the Statistical Analysis Research Committee since then. His retirement after 31 years as a professor allows him more time to spend on sabermetric research. The completed chapters of his book reviewing the sabermetric literature can be found at charliepavitt.home.blog; the rest of the book is in progress. He is happy to be contacted at chazzq@udel.edu.

Notes

- Well after completing this manuscript, presenting it at a regional SABR convention, and submitting it for publication, I learned that Mark Armour and Daniel R. Levitt had previously performed an analogous study; Mark Armour and Daniel R. Levitt, “Baseball Demographics, 1947-2016,” https://sabr.org/bioproj/topic/baseball-demographics-1947-2016/.

- Marc Lavoie, “Stacking, Performance Differentials, and Salary Discrimination in Professional Ice Hockey: A Survey of the Difference,” Sociology of Sport Journal 6, no. 1: 17-35; John Valentine, New Racism and Old Stereotypes in the National Hockey League: The ‘Stacking’ of Aboriginal Players into the Role of Enforcer, in Race and Sport in Canada, ed. by Danelle Joseph, Simon Darnell and Yuka Nakamura (Toronto: Canada Scholars’ Press, 2012): 107-135.

- J. R. Woodward, “Professional Football Scouts: An Investigation of Racial Stacking,” Sociology of Sport Journal 21, no. 4 (2004): 356-375; Kyle Siler, “Pipelines of the Gridiron: Player Backgrounds, Opportunity Structures and Racial Stratification in American College Football,” Sociology of Sport Journal 36, no. 1 (2019): 57-76.

- Wilbert M. Leonard II, “Stacking in College Basketball: A Neglected Analysis,” Sociology of Sport Journal 4, no. 4 (1987): 403-409; Rodolphe Perchot, Florent Mangin, Philippe Castel and Marie-Françoise Lacassagne, “For a Socio-Psychological Approach to the Concept of Racial Stacking,” European Journal for Sport and Society 12, no. 4 (2015): 377-396.

- Joe A. Maguire, “Race and Position Assignment in English Soccer: A Preliminary Analysis of Ethnicity and Sport in Britain,: Sociology of Sport Journal 5, no. 3 (1988): 257-269.

- James E. Curtis and John W. Loy, “Race/Ethnicity and Relative Centrality of Playing Positions in Team Sports,” in Exercise and Sports Sciences Review Vol. 6, ed. Robert S. Hutton (Philadelphia: Franklin Institute, 1978): 285-313.

- Aaron Rosenblatt, “Negroes in Baseball: The Failure of Success,” Trans-action 4, no. 9 (1967): 51-53.

- John W. Loy and Joseph F. Elvogue, “Racial Segregation in American Sport,” International Review of Sport Sociology 5, no. 1 (1970): 5-23.

- Loy and Elvogue, “Racial Segregation in American Sport.”

- Satya R. Pattnayak and John Leonard, “Racial Segregation in Major League Baseball, 1989,” Sociology and Social Research 76, no. 1 (1991): 3-9.

- G. Leticia Gonzalez, “The Stacking of Latinos in Major League Baseball: A Forgotten Minority?,” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 20, no. 2 (1996): 134-160.

- Robert Arthur and Daniel R. Epstein, “Why are there no Black catchers?” Baseball Prospectus, July 31, 2020, https://www.baseballprospectus.com/news/article/60634/moonshot-why-are-there-no-black-catchers/; Claire Smith, “What happened to the African American catcher?” The Undefeated, April 15, 2020, https://theundefeated.com/features/what-happened-to-the-african-american-catcher/.

- Curtis and Loy, “Race/Ethnicity and Relative Centrality.”

- Earl Smith and Wilbert M. Leonard II, “Twenty-Five Years of Stacking Research in Major League Baseball: An Attempt at Explaining this Re-Occurring Phenomenon,” Sociological Focus 30, no. 4, (1997): 321-331.

- Marshall H. Medoff, “Positional Segregation and Professional Baseball,” International Review of Sport Sociology 12, no. 1 (1977): 49-54.

- Allen L. Sack, Parbudyal Singh, and Robert Thiel, “Occupational Segregation on the Playing Field: The Case of Major League Baseball,” Journal of Sport Management 19, no. 3 (2005): 300-318.

- Curtis and Loy, “Race/Ethnicity and Relative Centrality.”

- Gerald W. Scully, “Discrimination: The Case of Baseball,” in Government and the Sports Business, ed. Roger G. Noll (Washington, DC: Brookings Institute, 1974): 221-273).

- N. Guppy, “Positional Centrality and Racial Segregation in Professional Baseball,” International Review of Sport Sociology 18, no. 4 (1983): 95-109.

- Marc Lavoie and Wilbert M. Leonard II, “In Search of an Alternative Explanation of Stacking in Baseball: The Uncertainty Hypothesis,” Sociology of Sport Journal 11, no. 2 (1994): 140-154.

- Guppy, “Positional Centrality and Racial Segregation.”

- Pattnayak and Leonard, “Racial Segregation in Major League Baseball.”

- Gonzalez, “The Stacking of Latinos in Major League Baseball.”

- Benjamin Margolis and Jane Allyn Piliavin, “Stacking in Major League Baseball: A Multivariate Analysis,” Sociology of Sport Journal 16, no. 1 (1999): 16-34.

- Sack, Singh, and Thiel, “Occupational Segregation on the Playing Field.”

- Arthur and Epstein, “Why are there no Black catchers?”