‘Their Throws Were Like Arrows’: How a Black Team Spurred Pro Ball in Japan

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in the 1987 SABR Baseball Research Journal.

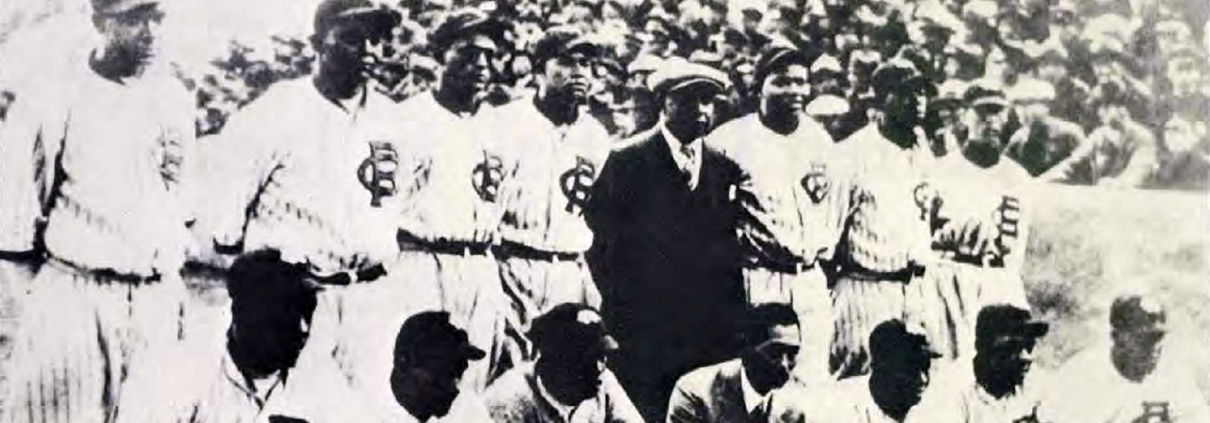

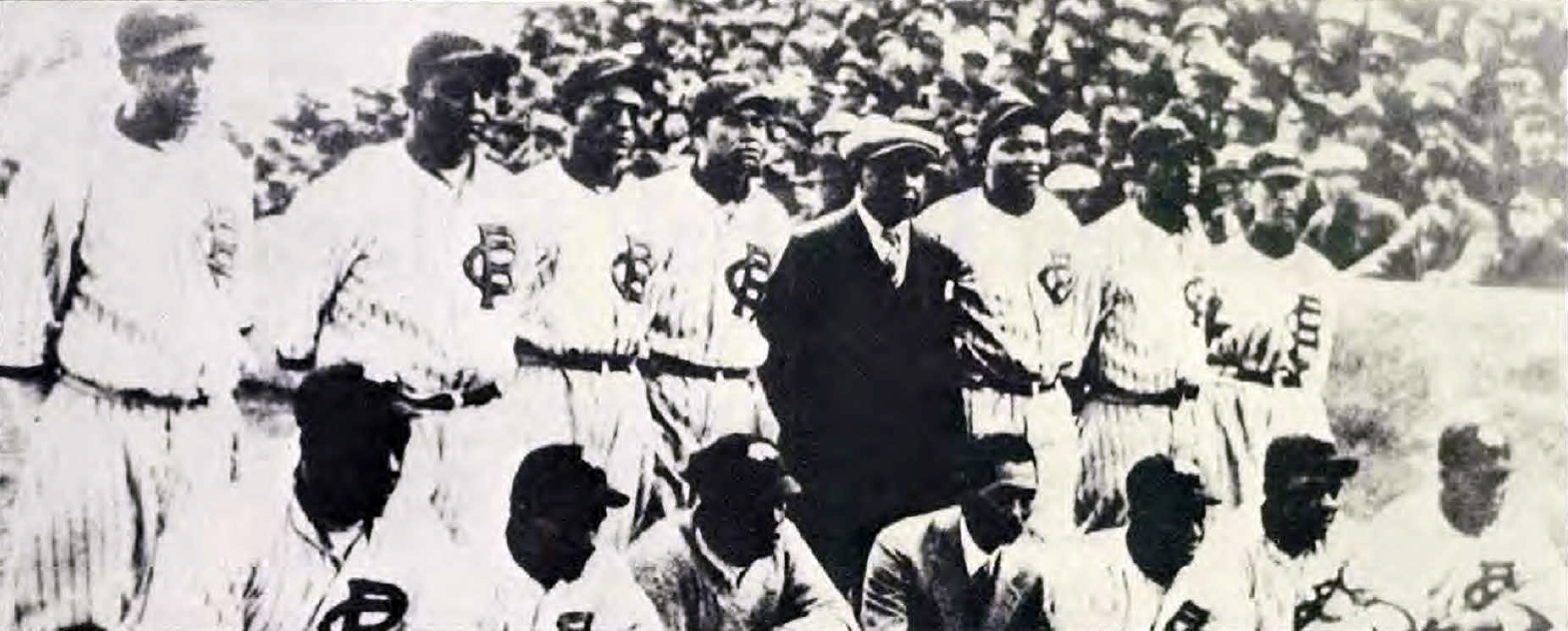

1927 Philadelphia Royal Giants in Japan (COURTESY OF JOHN THORN)

There were no professional baseball teams in Japan before 1935. Baseball had been introduced into this country long before that, but our teams were all amateur. Why were professional teams born in quick succession in 1936?

Quite simply, the visits of major leaguers. In 1931 an all-star team including Lefty Grove, Mickey Cochrane, Lou Gehrig, Rabbit Maranville, Lefty O’Doul, and Al Simmons visited Japan. Baseball fans were astounded at their overwhelming superiority: They played seventeen games, and won all of them.

Three years later, another American team arrived with Babe Ruth on it. Streets were crowded with people welcoming them. They won all eighteen games, and created a strong enthusiasm for baseball in Japan.

But these visits alone did not create professional baseball in Japan. Another professional team — a black club called the Philadelphia Royal Giants — had visited in 1927 and then again in 1932. It seems quite strange that this team has scarcely been mentioned in Japanese baseball books. The reason may be that the white Americans’ visits were sponsored by the Yomiuri newspaper, which had one of the biggest circulations in Japan. Yomiuri was already thinking of having the first professional team in Japan. They gave the tour nationwide publicity, with the result that all Japanese knew about the visits and adored the team’s stars.

On the other hand, the Philadelphia Royal Giants were not sponsored by any newspaper. They seem co have arrived through the efforts of a Japanese promoter named Irie, who lived in America, and he must have done little publicity work.

It was only by chance that I became interested in the team. Negro League historian John Holway wrote me a letter, asking for information on Biz Mackey’s hitting the first home run ever in Jingu Stadium, Tokyo. I was surprised to hear about this, because we have often been told that the first home run in the stadium was hit by the premier college slugger of the time, Saburo Miyatake of Keio University. After doing some research, l found that Holway was accurate. This was the beginning of my probe into the visits of the black team.

It was lucky for me that I was able to meet some people who had games with the Giants more than fifty years ago. It was fortunate, too, that the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame still preserves some of the news articles about their games, though they are not detailed.

The Philadelphia Royal Giants were a big surprise to the Japanese players. Saburo Yokozawa, who played second base on a Japanese team, says, “I still remember how surprised we all were. I can even call back some faces of the Giants. I can’t forget the big hit by Rap Dixon at Koshien Stadium. It flew well over the center fielder and hit the fence on the fly. The park was far bigger then than it is now, and you must bear in mind that the balls used then were still dead balls.”

No Japanese player could expect to hit that far. In Dixon’s honor, a white mark was painted on the point of the fence, with his name on it. This mark remained there for a long time before the fence was torn down to make a bleacher.

Biz Mackey’s home run, the first in Jingu Stadium, should be even more celebrated. The stadium had been completed in October of 1926, and no one had hit one over the fence. Mackey did it in a game against the Fresno, California team, which happened to be here at that time. It was a semipro team, made of Japanese players who lived in Fresno. The hit flew over the fence, bounced off the grass bleacher, and disappeared beyond it. Altogether, Mackey hit three over the fences in Jingu during the 1927 tour.

Dixon’s drive to the Koshien fence and Mackey’s home runs established the power of the black players, since these were the biggest parks in Japan. The Giants’ fielding and throwing also astonished the Japanese. In the words of old Japanese, “Their throws were like arrows.”

Their running was another phenomenon. They stole bases every time they needed to. The records show that they won all but 1 of their 48 games.

As the days passed, black players attracted much respect from Japanese players and fans for their gentle behavior. They never even complained about their one loss — a controversial 1-0 victory for the Japanese team. In fact, it should have been at least a draw. As Jyukichi Koshiba, who played on the Japanese team, explained:

“The record might read that the Daimai team won in the game, but it was a win unlawfully acquired. There was one out. Runners were on third base and first base. The next batter hit a big fly to right field. We got two outs. But after the catch, the runner on third base scored. And the other runner was still running. He tried to go back to first. The ball was thrown by the right fielder to the base before he reached it [but after the runner on third had scored]. Three outs. As you know, one run should have been given to the Giants. Nevertheless, the umpires admitted no score. Their assertion was that it was a double play. But the judgment was wrong.”

Said second baseman Yokozawa, “The black players well knew that it was a misjudgment. A runner reached home before the third out was called. Double play? It was out of the question. They knew it. But no black player got angry at this, and soon allowed that wrong call. They seemed to be saying, ‘It’s okay. If you say it’s a double play, it is a double play.’ We Japanese players, too, knew it was the umpires’ fault. But the Giants were too clean-cut. We lost the chance to make it correct.”

In checking the record of the game, I found that the third base runner was Rap Dixon, and the other was Pullen. The batter was Cade.

This is not the only example of the Giants’ gentle attitude. In the game against the Tomon club of Waseda University, Mackey was hit by pitcher Wakahara. Mackey made a face. The pitcher felt small, and, caking his cap off his head, bowed politely to Biz Mackey. In turn, Mackey made a Japanese bow in the same polite way. A happy mood prevailed.

The Giants were gentle and kind-hearted, both on and off the playing field. After expressing surprise at the Giants’ size, Takeshi Miwna wrote in the June 1927 issue of Baseball World:

But their behavior is quite gentle. In the hotel, they keep quiet. The voices they use with each ocher are calm, and hardly audible. You would hardly know of their existence. When I asked them about the games in this country, they gave me some comments but in a very humble way. They are modesty itself. You’d think the voices of housewives in the back street of the hotel are far noisier. When there is no game, they enjoy billiards, or walking in the neighborhood. They show great love for children and play with them happily. I heard that they sometimes go to cafes where young girls serve tea or alcoholic drinks, but they never become rude. Not even a quarrel has arisen between them in these long months of travelling, I heard. I asked them about their impressions of Japan. Their first answer was they are really happy, and appreciated Japanese hospitality. In Kyoto, they enjoyed watching Miyako-Odori, traditional dances by geishas. In Tokyo, too, they visited the Shinbashi-Enbujyo Theater, and enjoyed Azuma-Odori dancing. They seem to be entranced by their beauty. One of them said, ‘I feel very happy. I am fortunate. We came here to play games, and had the chance to see many beautiful things. I wish I could tell my family and friends how happy we are. I wish they all could see this country of Japan.’

The Giants sent a message to Japanese baseball fans. I found a Japanese translation of it in Asahi Sports of April 1927. Having no way to find the original, I’ve tried to put it in English again. This is not the exact message by them, but it should give you an idea of what they wanted to say.

After playing some games against Japanese baseball teams, we felt our respect growing. The biggest surprise we had here was the fact that Japanese baseball has already got the very essence of the game. Before we came over here, we often wondered, and talked between ourselves about baseball in Japan. Our conclusion was that Japanese basehall would still be immature. But when we had games against teams here, we could not help being stricken dumb by the wide difference between our surmise and reality.

While at sea, we dreamt of the country of Japan, which we were approaching, and talked about it many a time. One of our greatest concerns was — what kind of parks do the Japanese have? We were unanimous in deciding that Japanese ballparks would surely be very small, poorly equipped ones. They would be no bigger than Class D ballparks in the States. When we found ourselves in the magnificent Jingu Stadium, which is situated in the outer garden of solemn Meiji Shrine, and in the grand and imposing Koshien Stadium, we had to admit that we had had a double misunderstanding. Particularly, Koshien Stadium is grandeur itself. It has a capacity of more than 50,000 people, and is as big as any in the United States.

In the games, we marveled at the dauntless plays by Japanese players. The offense was not only brave but also understood inside baseball. Our team has so far lost one precious game against the Daimai Club. It was the game in which ace pitchers of both teams — Ono of Japan and Mackey of the Giants — showed a keen competition. Though we were defeated in the game, we feel proud that we played baseball of the highest level. We feel admiration for the crafty pitching Ono showed. But more than that, the team play shown in the game by the Japanese called forth our unbounded admiration.

We do believe that baseball will have prosperity here. And our admiration should not be confined to the techniques Japanese players have. Their sportsmanship, too, was worthy to be praised. Frankly speaking, no ocher people in the world play the game so joyously, disregarding the result of the game. Fans, too, we find sportsmanlike and gentlemanly. We would like to say true enjoyment of sports is to be gotten only by people like the Japanese. We do hope that Japanese baseball will have permanent prosperity. And at the same time, through Asahi Sports, we would like to extend our hearty thanks for many kindnesses shown us since we arrived here.

April 8, 1927, Philadelphia Royal Giants

Has any other team left such a courteous message to the baseball fans here? I don’t think so. A member of the Giants, Frank Duncan, told John Holway; “We sailed out of San Pedro, California, to Yokohama, Japan. Went on La Plata Maru boat. Took us nineteen days going over. The people were wonderful over there. I loved them. I hated to see them go to war. Wonderful people, the most wonderful people I’ve come in contact with. We played all over — Osaka, Kobe, and into Nagasaki. They had some nice teams over there in Japan, but they weren’t strong hitters. Pretty good fielders, fast, good baserunners. … “

A former Japanese player, Yasuo Shimazu, writes: “Several baseball teams visited Japan in those days from abroad. College teams, semi-pros and professionals. Each impressed us. We could hardly expect to defeat any one of them. So it would have been too much expectation to hope for their uttermost sincerity in all games. To be sure, one team showed quite strange sights. All the players, except the battery and first baseman, took off their gloves when they were on defense. Some infielders turned the backs to batters, and showed their faces between their legs. These kinds of deeds might have been intended for the enjoyment of spectators. But we could not feel happy at them. In this respect, the Royal Giants played in a right way. They, too, might have felt nothing of Japanese competency inwardly, but they showed no sign of it. They kept on playing in a sincere manner. One of the examples was the case of Mackey’s throwing. While they were practicing before the games, he threw from home to second base in a sitting position. We were simply surprised at his hard throwing. But once the games began, he didn’t do that. After catching balls, he stood up and threw in quite a fundamental way. They had no signs of negligence.

“Some players of other teams made several kinds of funny shows. Some danced around before the spectators, and made strange sounds like those made by fowls. The players themselves! Those were the last acts we expected of players. The Royal Giants didn’t display these kinds of deeds. Nor did they play pranks outside the park, which players of other teams often did. A member of the Giants, whose name I forget, said to me, ‘I like Japan and the Japanese people. There is no racial barrier here. What a good country! I’d like to come back here again.’ I believe that this was the manifestation of his true heart. Putting this and that together, I’d like to emphasize that the players of the Royal Giants were real Gentlemen.”

Shimazu reminds us of the visits by major-league teams. In a game held in the rain at Kokura in 1934, Babe Ruth took to the field as a first baseman with a Japanese umbrella over his head, and Lou Gehrig, who was playing as a left fielder, had rubber rain shoes on. In another game, when Lefty Grove was pitching, left fielder Al Simmons laid himself on the field to show he had nothing to do but lie down and watch what Lefty was doing. They may have been intended their actions to be a show, but many Japanese fans weren’t altogether happy.

The Royal Giants did put on a show one time. It was at Jingu Stadium after their last game in Tokyo in 1927. The Giants performed not in a mocking, but in a sincere way. Everything they did had something to do with baseball itself. No singing, no dancing, Rap Dixon threw a “straight” ball directly to the bleacher from home plate. Biz Mackey knocked balls into the bleacher from home. Rap ran around the diamond in fourteen and one-fifth seconds, and Frank Duncan in fifteen seconds. These displays helped Japanese fans gain additional respect for the black team.

Barnstorming black teams often sang and danced. Why didn’t the Giants? I think the reason is quite simple. They had no need to act like clowns. Japan has had no segregation. We have had a practice of welcoming every visitor from abroad as an honored guest — even if he is here for commercial reasons. The Royal Giants were guests, and they could act quite naturally. They felt no stress. So … “Was it a double play? Oh, yes, if you think so, it’s a double play.”

I think this relaxed mood was very important to the history of Japanese baseball. The major leaguers played like textbooks, but they were too much for the Japanese players. Japanese baseball was only a baby, delicate and fragile. Everything the big leaguers had was too big for the baby. Every play, every show the major leaguers made could not help making the Japanese player recognize how small he still was. If he had seen, at that time, this big textbook alone, he might have been killed by the weight. David Voigt makes a similar point when he speaks of the attempts to plant baseball in Great Britain in America Through Baseball:

… the three great baseball missions were all undertaken under the mistaken notion that baseball could best be spread by professional advocacy in the form of a spectacular display of the game as played by skilled professionals. While by no means a total failure, the results of these displays were disappointing and sometimes even counterproductive … the very polish of the American professionals hurt the spread of baseball in Britain.

It goes without saying that Japan had quite a different sporting and historical background from that of England, and the relationship between Japan and America is not the same as that between Britain and the United States. Nonetheless, Voigt’s point is well taken.

Why did the transplanting of baseball succeed in Japan? In my opinion, the reason was that the Japanese had a good shock absorber. “Spectacular display” by a “great baseball mission” could have been counterproductive here, too. But we were lucky enough co have the chance to neutralize the shock. The Royal Giants’ visits were the shock absorber. Baseball has in it many elements that appeal to the Japanese mind, and it may safely be said that professional baseball would have been born in the course of time. Without the visits of the gentlemanly and accessible Royal Giants, however, I don’t think it would have seen the light of day as early as 1936.

Another letter from Shimazu includes these very sentiments: “We heard that, though they [the Royal Giants] were not major leaguers, they were as strong as, or stronger than, the majors. I myself played in some games against them, and saw many of their games here. I know it was true. But I’m still in wonder. I have been thinking of it in my sickbed since I got your letter. Why was it that we felt we could nearly win? We had the feeling after the game against the Giants that if we had tried a little harder, we could have won. In the games against the major leaguers, we were treated like children. We were at their mercy. We could do nothing. Babies against grownups — that was the impression we had. But in the games against the Giants, the whole impression is quite different. Of course, the All-American team was a star-packed team, and the Royal Giants wasn’t. But as a whole, they could not have been so far away from the major leaguers. Then why was it that we almost always had close games? Was their batting not so good? Look, they blasted long hits when they were needed. They seemed to be able to hit as they wished.

“Here I’d like a jump up to a bold conclusion. Didn’t they have abundant showmanship? In games they could have scored many more runs. But they took — or tried to take — the least runs needed. They never tried to take too much score. In so doing, they attracted the interest from the spectators, as well as from the opponent players. Even if a Japanese team didn’t win, the hope remained. More spectators visited the next day …”

Regretfully, not all games were reported in detail. In the scarce records we have, we can see proof of Shimazu’s remark. When the Giants scored many runs, the Japanese team scored some runs, too. When the Japanese didn’t score, the Giants often didn’t score many, either. (To be sure, wide margins occurred in some games in small towns. The Giants were probably unable to keep the score close against really inferior opposition.)

The Giants seem to have let Japanese teams score some runs in the last inning if it didn’t affect the result. This reminds us of the attitude of Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and other Negro League players in games against the Marine Corps; they deliberately gave the opponents a run to save face.

The Giants didn’t push their powers too far. They were reserved, and their reserve might be said to have been for commercial purposes. But even so, how fortunate it was for Japanese baseball.

There is no denying that the major leaguers’ visits were the far bigger incitement to the birth of our professional league. We yearned for better skill in the game. But if we had seen only the major leaguers, we might have been discouraged and disillusioned by our poor showing. What saved us was the tours of the Philadelphia Royal Giants, whose visits gave Japanese players confidence and hope. It is unfair that no words of gratitude have been spoken by the Japanese to this team.

KAZUO SAYAMA, a SABR member since 1983, is the author of more than 40 books on Japanese baseball history. He was elected to the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame in 2021.