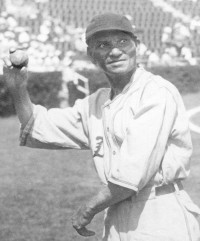

Sol White

This article was written by Jay Hurd

This article was published in From Rube to Robinson: SABR’s Best Articles on Black Baseball

Racial discrimination did not miraculously disappear in 1863 with the Emancipation Proclamation, nor did it cease with Civil War’s end in 1865. However, even as race relations remain a topic in 2011, the process for dealing with race faced an evolution. Speaking to this evolution, Jerry Malloy, in his Introduction to Sol White’s History of Colored Baseball, states that:

Racial discrimination did not miraculously disappear in 1863 with the Emancipation Proclamation, nor did it cease with Civil War’s end in 1865. However, even as race relations remain a topic in 2011, the process for dealing with race faced an evolution. Speaking to this evolution, Jerry Malloy, in his Introduction to Sol White’s History of Colored Baseball, states that:

Sol White was a member of a tragic generation of African Americans, born within a few years of the Civil War. He and his contemporaries reached adulthood at a time, in the mid-1880s, when the brutal protocols of racial discrimination that soon would follow seemed by no means inevitable.1

Solomon White — also known as King Solomon White, or Sol White — was born in Bellaire, Ohio on June 12, 1868, 3 years and 2 months after Lee met Grant in Appomattox Court House. One of baseball’s early historians, White was born in a northern state very near West Virginia, a state which had been accepted into the Union in 1863, only five years before his birth, and where much of his early career in baseball would occur.

Very little is known of Sol White’s early years — his parents/family, his education, his social life — according to sources, including Jerry Malloy, Negro League historian. However, it is known that while in his teens, he began, in 1883, what would become a 40-year career in professional baseball. In a newspaper piece in the Pittsburgh Courier of March 12, 1927, Floyd J. Calvin states that:

Bellaire, Ohio, where Sol was born, had three white teams, the Lillies, the Browns, and the Globes. As a boy Sol hung around the Globes and then came the time when the Globes had an engagement with the Marietta team. One of the Globe players got his finger smashed, and since they all knew Sol, the captain pushed him into the game.2

The captain of the Marietta team was Ban Johnson who would later become president of the American League. Floyd Calvin adds, “Sol takes pride in having played against Ban when he was an obscure captain of a hick town club.”3

Sol White’s professional career began in 1886 after 3 years with the barnstorming Bellaire Globes. In 1886, Sol played with the integrated Wheeling (West Virginia) Green Stockings of the Ohio State League. While with the Green Stockings he played third base, and hit .370 in 52 games. At this time, his presence on a white team, in a predominantly white league, was not problematic. Indeed, African American ballplayers — John W. “Bud” Fowler, George Stovey, Frank Grant, Jack Frye, and Robert Higgins — played regularly in barnstorming and professional leagues, including the minor leagues of major league baseball. By 1887, however, white player fomented anti-black sentiment led to opposition integrated teams. Change was clearly in the offing. Sol left Wheeling, in 1887, to play with the Pittsburgh (Pennsylvania) Keystones. After a mere 13 games, he left the Keystones as that team and a newly formed League of Colored Baseball Players (or National Colored Baseball League) folded. He continued to play baseball, however, when he returned to Wheeling.

In 1888 Sol returned to the Keystones — at this time not a professional team – who were playing in a 4-team tournament with the Gorhams (New York), the Red Sox (Norfolk, Virginia), and the Cuban Giants (Trenton, New Jersey). The Keystones played well, losing only to the powerful Cuban Giants. The other teams, surprised by the Keystone’s success, did note the presence of one man “other than home talent [i.e., professional caliber].” That man was Sol White.4

Having established himself as a talented ballplayer, Sol spent the 1889 season with the Gorhams, of New York City. Despite the New York City component of the team’s name, the Gorhams represented Easton, Pensylvania, in the Middle States League.5 The Gorhams did not fare well that season, and left the league before the championship would be won by the Cuban Giants of Trenton, NJ. In 1890, feeding what would become a regular occurrence, not without legal and personal battles, players left the Cuban Giants. The players fled the miserly ways of John M. Bright to glean the generosity of J. Monroe Kreiter of York, Pennsylvania. Bright maintained a Cuban Giants team, but Sol White joined the Monarchs of York.

By 1891, amidst additional controversy, owner Ambrose Davis renamed his Gorhams the Big Gorhams. Players, including Sol White, again leapt at an opportunity for more money and became members of Davis’s new team. The team was successful, but, as did other African American teams, struggled financially. White found it necessary to play, in 1892, for the Pittsburgh Keystones and for a team formed at the Hotel Champlain, Bluff Point, New York (while with the Hotel team he also waited on tables). In 1893 and 1894 he played for J.M. Bright’s “revived Cuban Giants, the only black professional team in the country in either season.”6

Although primarily an infielder, at 5’9”, 170 pounds, he could play nearly any position. He clearly exhibited a high caliber — major league level – of play.

Although Adrian “Cap” Anson would be afforded much credit for forcing “Negroes out of organized baseball”7, it was evident “that a majority of white baseball players in 1887, both Northerners and Southerners, opposed integration in the game.”8 White players now regularly refused to play with African-Americans. By the turn of the century, segregation in baseball became the norm. Sol did play in the white minor leagues, on African American teams, and would soon join others in the not-uncommon movement from one all-black team to another. During his five years in white baseball. He never hit lower than .324; and in 159 minor league games he hit .356, scored 174 runs, and stole 54 bases. 9

In spite of the many obstacles Sol continued to play into 1895 when he played 10 games for a team in the integrated Western Tri-State League, in Fort Wayne, Indiana. In that same year, he joined the Page Fence Giants of Adrian, Michigan. This team, funded by the Page Woven Wire Fence Company, did not have a home field and travelled by private rail coach. Experiences with this team would continue to feed Sol information to be recorded later in his life, when Sol White baseball historian would emerge. Sol remained with the Page Fence Giants for one season, batting a healthy .404. In 1896, White joined the Cuban X-Giants, and would be defeated by the Page Fence Giants.

In 1896, Sol enrolled in Wilberforce University in Xenia, Ohio, as a theology major.10 Wilberforce University, founded in 1856, was named after an English abolitionist and supported by the African Methodist Episcopal Church. As with much of Sol White’s life, little is known about his academic experience at Wilberforce, and it is not clear if he graduated. However, he did attend a university and studied at that level for a number of years. Jerry Malloy states that:

He received high grades in a curriculum that included reading, grammar, arithmetic, physiology, history, elocution, spelling, and U.S. history. Meanwhile, he developed the innate interest in history that ultimately made him the Livy [ancient Roman historian] of African American baseball.11

While at Wilberforce, White began to form friendships and partnerships which would guide him into positions of management and ownership of African American baseball teams. Preparation for his role as historian of African American baseball was nearly complete.

In 1897, Sol returned to the Cuban X-Giants where he remained for 3 seasons. By 1899, the X-Giants held enough talent to defeat the Chicago Columbia Giants — formerly the Page Fence Giants – 9 out of 14 games. After the 1899 season, manager John Patterson of the Chicago Columbia Giants, aware of White’s talent, signed him for the 1900 season. Although White noted that the Columbia Giants was “the finest and best equipped colored team that was ever in the business”,12 he remained with the team for only one season. After another brief stint with the Cuban X-Giants in 1901, Sol stepped into a partnership with H. Walter Schlichter and Harry Smith — white sports writers from Philadelphia — to form the Philadelphia Giants. White served as player-manager the Philadelphia club until 1909.

From 1902 to 1907, White and his Philadelphia Giants were quite successful due, in large part, to a pitcher named Rube Foster. In 1907, however, Rube Foster left the team to become a member of the Leland Giants of Chicago. Foster would soon compete for talent, assuming control of Frank Leland’s Giants, and thus begin his movement toward the founding of the Negro National League in 1920.

White saw his Philadelphia Giants win numerous regular season games, as well as black championships. Additionally, his Giants posted many wins over white teams, such as those in the New England League. He even issued challenges to National and American League champions — notably a 1906 challenge to the winner of the major league World Series between the Chicago Cubs and the Chicago White Sox (a challenge unanswered). However, it was while with the Philadelphia Giants that White published his Sol White’s Official Base Ball Guide. Copyrighted in 1907 by Sol and H. Walter Schlichter, sports writer and sports editor of the white newspaper, the Philadelphia Item, and White’s Philadelphia giants partner13. This is the work which helps to define Sol White, the ball player, the historian and the man.

White’s playing career would not end until 1911. His final active roles in baseball included: managing of the Boston Giants in 1912; serving as secretary for a Columbus team of the Negro National League in 1920; managing the Fear’s Giants of Cleveland (a black minor league team) in 1922; managing the Cleveland Browns of the Negro National League in 1924; and managing the Newark Stars (or Browns) of the Eastern Colored League in 1926.

Sol White played baseball with talent and drive; he supported and valued his fellow players. White took great pride in his play, and in the African-American teams. He also played for the money, although salaries for him and his fellow ball players were substantially lower than salaries for white major leaguers (he noted that “the average major leaguer made $2,000.00 in 1906, while the average black netted only $466.00).14

History shows that Sol White, with Rube Foster, and others, “had held black baseball together throughout 60 years of apartheid, making Jackie] Robinson’s debut possible”,15 Sol White’s many contributions to baseball became more evident by the 1920s. In 1922, when he briefly managed a black minor league team, the Giants of Cleveland, Catcher William “Big C” Johnson, whose experience included a stint on a U.S. Army baseball team which fielded, among others, Wilbur “Bullet” Rogan, said that Sol White is “the best educated man I ever played with. Sol wanted what they never were able to get — a reporter to keep records. They never had enough money to hire a man like that.”16

John Holway refers to Sol White as “an infielder who would go on to become the most influential figure in the first decades of Negro baseball.”17 Today, referred to as a Renaissance Man, Sol White is remembered for his great contributions to the recording of baseball history. White stated that:

Baseball is a legitimate profession. It should be taken seriously by the colored player. An honest effort of his great ability will open the avenue in the near future wherein he may walk hand in hand with the opposite race in the greatest of all American games — baseball.18

When no longer directly involved with the game, White maintained baseball connections through writing columns for the New York Amsterdam News and the New York Age. It is apparent that Sol hoped to update, even on an annual basis, his Base Ball Guide. He did maintain correspondence with H. Walter Schlichter, and in a letter of 1936, Schlichter suggests:

Why not see the Editor of your colored paper and try to sell him a history of colored baseball which you could write either as a single article or as a series. Except for recent years you have all the data in the book and I would be glad to furnish the cuts and pictures. It looks to me to be worth trying.19

Sadly, the resources were not available for him to continue publishing his Guide.

White died, penniless20, at the age of 87 on August 26, 1955. The American National Biography states that he died in Harlem, New York City where he lived for a number of years, although the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum notes that he died in Central Islip, New York. Sol White is buried in Frederick Douglass Cemetery in the Oakwood neighborhood of Staten Island, NY.21 In 2012, the Negro Leagues Baseball Grave Marker Project, whose mission is to identify the final resting place of Negro League Baseball players and mark the graves of those found unmarked, delivered the granite marker for King Solomon “Sol” White to the Frederick Douglass Memorial Park of Staten Island, New York.22

Sol was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, via a special Negro Leagues Committee, in 2006. His plaque in the Hall identifies him as an “outstanding player and manager” of the “Pre-Negro Leagues, 1887-1912” and the “Negro Leagues, 1920-1926”. The plaque also recognizes “Sol White’s Official Base Ball Guide of early black baseball teams, players, and playing conditions.”

Perhaps it is his Base Ball Guide which best exemplifies Sol White the man. In his Guide he writes candidly and “as accurately as possible”23 to describe the makeup and history of African-American teams. In dedicating his work “To the players and managers of the past and present and the patrons of colored base ball”24 Sol demonstrates his real admiration for the game. He also reveals a desire to recognize baseball’s past, acknowledge its present, and step into its future. Sol lived to see Jackie Robinson play with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. As Frank Ceresi and Carol McMains note in their May 2006 Baseball Almanac article “Renaissance Man: Sol White”:

What quiet pride Sol [White] must have felt when, as an old man living alone in Harlem, he saw Jackie Robinson break down the blight on the game we now, quite antiseptically, refer to simply as the ‘color barrier.’

Sol White was known to be an intelligent and insightful man, using his mental acuity as well as his physical ability. For this he was respected by fellow players, owners, managers, promoters, rooters, and newspaper men. It is also for this that Sol White is respected and admired today.

Notes

1 Sol White. Sol White’s History of Colored Base Ball: With Other Documents on the Early Black game, 1886-1936. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), li-lii.

2 Calvin, Floyd J. “Sol White”. Pittsburgh Courier, March 12, 1927. White, 143.

3 Calvin, Floyd J. “Sol White”. Pittsburgh Courier, March 12, 1927. White, 144.

4 White, xxiv.

5 White, xxvi.

6 White, xxxi.

7 Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White: A History of Legendary Black Players and All Black Professional Teams before Black Men Played in the Major Leagues (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1970), 30.

8 Peterson, 30.

9 White, xxv.

10 Bernstein, David. “Solomon White,” American National Biography (New York: Oxford University Press), v.23, 239.

11 White, xlvii.

14 David Pietrusza, David, Matthew Silverman, and Michael Gershman, eds. Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia. (New York: Total/SPORTS ILLUSTRATED, 2000), 1221.

15 John B. Holway, Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers. (Westport, CT: Meckler Books, 1988), 7.

16 Holway, 7.

17 John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History. (Fern Park, FL: Hastings House Publishers, 2001), 21.

18 Pietrusza, 1221.

19 White, 157-158.