Roland Hemond: If You Can’t Take Part in a Sport, Be One Anyway, Will You?

This article was written by Mort Bloomberg

This article was published in 2008 Baseball Research Journal

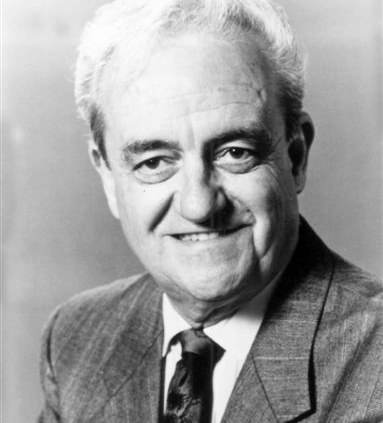

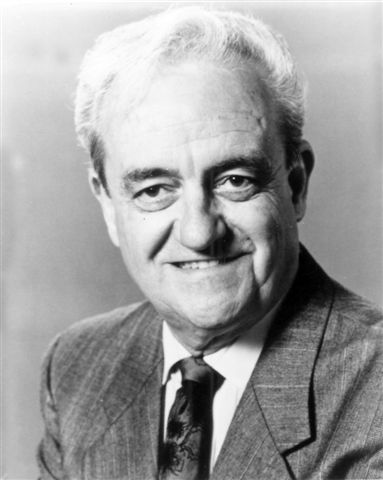

Roland Hemond has made lasting and unprecedented contributions to professional baseball with seven major-league teams. Born in 1929 to parents of French-Canadian heritage in Central Falls, Rhode Island, Hemond is one of the industry’s most respected and experienced executives.

Roland Hemond has made lasting and unprecedented contributions to professional baseball with seven major-league teams. Born in 1929 to parents of French-Canadian heritage in Central Falls, Rhode Island, Hemond is one of the industry’s most respected and experienced executives.

Hemond is also a member of one of baseball’s most distinguished multigenerational families. His wife, Margo, is the daughter of John Quinn, who as general manager for 28 years with the Braves and 13 with the Phillies won three National League pennants—including the flag atop the pole in right center field throughout the 1949 season next to Braves Field’s Jury Box—and one World Series championship in 1957.

Margo’s grandfather was Bob Quinn, a baseball magnate with four major-league teams, who during his playing days in the 1890s caught for several minor league clubs, some of whom he managed. As president and part owner of the Red Sox from 1923 to 1932, Bob Quinn was the bridge between owners Harry Frazee and Tom Yawkey (see article by Levitt et al. at page 35), and from 1936 to 1941 he served in the Braves’ front office. When his son John, the Braves farm director, became the general manager in 1945, his father took over as farm director for a year before his appointment as director of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Roland and Margo’s son Bob is part owner of the Sacramento River Cats, one of the great success stories in minor-league baseball. Two other children, Susan and Jay, have also worked in baseball. Additionally, Margo’s brother Bob had stints as general manager for the New York Yankees, Cincinnati Reds, and San Francisco Giants and spent fourteen years in the Cleveland Indians’ and Milwaukee Brewers’ front offices; her brother Jack was general manager of six minor-league teams.

ROLAND HEMOND’S CAREER IN MLB

Roland’s extraordinary career at the major-league level began when he joined the Boston Braves late in the year in 1951, after an apprenticeship with their Eastern League affiliate, the Hartford Chiefs. He worked as assistant secretary to John Mullen, who ran the Braves’ farm system (and would continue in that capacity after the franchise was transplanted to Milwaukee, remaining with the organization through 1960).

Fred Haney, the Braves’ manager, worked with Hemond during the club’s 1957 and 1958 championship seasons and later, as first general manager of the Los Angeles Angels, hired him as scouting and farm director in 1961. After a successful career there, Hemond was named general manager of the Chicago White Sox on September 14, 1970, and charged with the responsibility of rebuilding a franchise in decline. Hemond was named Major League Baseball’s Executive of the Year in 1972 by The Sporting News and again, this time by United Press International, in 1983, when he was the architect of a White Sox team that won the American League Western Division title (99—63) by a margin of 20 games (setting a record, now broken, for the era since divisions were introduced in 1969) over the second-place Kansas City Royals.

On departing the White Sox in 1986, after fifteen years there, he worked in New York in the commissioner’s office, as Peter Ueberroth’s special assistant. His next stop was as general manager of the Baltimore Orioles (1988—95). The 1989 team improved 32½ games in the standings from the previous season, and again Hemond was named Executive of the Year by The Sporting News. He left Baltimore after the 1995 campaign to work for the next five seasons as senior vice president of the Arizona Diamondbacks.

On November 30, 2000, Roland rejoined the White Sox to serve as executive advisor to newly appointed general manager Ken Williams, and with all of Chicagoland he celebrated the team’s World Series victory in 2005. He continued to advise and assist Williams until July 2007, when the Diamondbacks brought Hemond back to Phoenix, his family’s home for the past twelve years, and named him special assistant to team president Derrick Hall.

In 1992, Hemond, the chief architect of the Arizona Fall League (AFL), saw his work on that project come to fruition. The AFL serves as a graduate school for professional baseball’s top prospects. Now in its seventeenth season, the AFL has clearly paid dividends, as alumni of the league have collected Rookie of the Year honors in fourteen of the past seventeen seasons through 2008. In 2008 both winners, Geovany Soto of the Cubs and Evan Longoria of the Rays, had played in the AFL.

Hemond is president of the Association of Professional Ballplayers of America, a nonprofit organization that assists former and current players who are in need. He helped found the Professional Baseball Scouts Foundation, which assists longtime scouts in need of special support. In recent years he has worked to help players pursue their education online. At last count, more than 150 professional ballplayers have taken this path, for which Hemond was awarded an honorary degree by the University of Phoenix in 2006.

NATIONAL RECOGNITION

A nationally recognized ambassador of the game, Hemond was crowned “King of Baseball” by Minor League Baseball at their Winter Meetings banquet in 2001. In 2003 he became the first off-the-field recipient of the prestigious Branch Rickey Award, given to baseball people who contribute selflessly to their community and serve as strong role models for others.

In addition, four annual awards from four different organizations are named in his honor:

- from SABR, for meritorious service in scouting or in working with scouts (established 2001)

- from the Arizona Fall League, for longstanding service to professional baseball and a leadership role within the AFL (established 2001)

- from the Chicago White Sox, for dedication to helping others through notable self-sacrifice (established 2003)

- from Baseball America, for contributions to scouting and player development (established 2003)

And by way of saying Welcome Home to a man who got his start in baseball when the Braves were still in Boston and whose accomplishments off the field can be said to rival those of Spahn and Sain on it, the Boston Braves Historical Association inducted Hemond into its Hall of Fame in October 2007.

Fortunately for those who would like to enhance their store of baseball knowledge with some insight into this genuinely humble man, who is inclined not to talk about himself, many who have known him well over the years have been quick to describe his achievements and virtues. “I’ve known Roland for over fifty years,” Commissioner Bud Selig says of him, “and he is the classic baseball man. Nobody loves the game more.”

HEMOND RECALLS

Roland Hemond joined the Boston Braves at the majorleague level in 1951. In an interview in 2006, he recounted what it was like to be a baseball fan when there was no television and no sports coverage to the point of oversaturation.

The backdrop for the interview was Encanto Park, a few miles west of downtown Phoenix. It’s a public park, old and sprawling and in some ways spartan. It was quiet on the morning we sat down to chat at a picnic table. The locale was ideal, affording a flashback to Braves Field in its final year of occupancy before Lou Perini moved the team to Milwaukee.

Here are some warm, engaging glimpses into when Hemond’s lifelong love affair with baseball and baseball people began.

My buddies and I would hang around the corner drugstore talking baseball and couldn’t wait for the latest edition of the Boston Daily Record to be delivered. I remember spreading the paper on the floor at home and lying face-down, just devouring the box scores. The stories in those days were so much more descriptive of the plays—the description of a game-saving play by Dom DiMaggio, for instance. It was almost like listening to the games on radio, as you picture everything that’s taking place. The stories today don’t go into as much depth because it’s assumed that people saw them on TV. But in those days, you had to picture plays in your mind. Since the writers back then didn’t necessarily go to the clubhouse for postgame comments, they would go into great detail about, let’s say, a game-ending double play. How it went from Eddie Miller deep in the hole at shortstop to Bama Rowell at second and over to Buddy Hassett at first base. It was also great reading about the trades that were made and why—as it is today. You became engulfed in it.

Radio added a new dimension to Hemond’s love for baseball. In those days games generally began at 3 P.M., and as soon as school let out he would rush home to listen to the latter part of the game. Of all the announcers he heard as a youngster, Jim Britt made the most lasting impression.

He would end the broadcast saying, “If you can’t take part in a sport, be one anyway, will you?” That was his closing comment. He had a great, melodious-type voice and actually announced the home games of both the Braves and the Red Sox. You became attached to him as well, and the fact that he was the voice of both helped to create a strong interest in the two clubs. Another announcer, Bump Hadley, I remember because I saw him pitch on opening day at McCoy Stadium in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, when the park opened in 1942, the year after his major-league career was over.

Hemond played one game in high school against Chet Nichols, who as a rookie with the Braves would go on to win the National League ERA crown in 1951. “I always kidded Chet that I hit a line drive off him to the third baseman so hard I never left the box. But to see him pitch in the majors after I played high school against him was a big thrill for me.”

Hemond talks about two individuals from his youth who meant a great deal to him.

When I was playing on Sunday League, Boys Club, and Legion teams, my great friend Bob Brown of Central Falls, Rhode Island [not to be confused with the New York Yankees third baseman and American League president], was the shortstop and I was the second baseman, so I was Bobby Doerr and he was Johnny Pesky. I told Bobby later on that he didn’t have to worry about me taking his job.

In addition to Bob Brown, one of the best friends in my life was Leo Labossiere, who was a great all-around athlete in baseball and basketball at Providence College and had been my high-school coach as well as helping me learn the fundamentals of both sports. It’s amazing how great friends become very successful in their field and the friendships endure throughout one’s life. Both Bob and Leo are very special in my life.

In 1948, Hemond was a storekeeper first class in the Coast Guard, handling pay records at Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn.

I saw more Red Sox games at Yankee Stadium than I did at Ebbets Field seeing the Braves. The Red Sox kept losing in New York. They had a bad record there through the years and some sad memories. It was a pretty good haul for me from Floyd Bennett Field to see the BoSox take on the mighty Yankees. We had to take the bus to the Flatbush Avenue subway and then all the way to the north side in the Bronx to Yankee Stadium, but I made it as often as I possibly could. That vast left field in Yankee Stadium would do the Red Sox in because Doerr and Vern Stephens and right-handed pull hitters like them were victimized by Death Valley, as they called it. Left field was a lot deeper in Yankee Stadium then than it is now. Sox long-ball hitters paid the price of Fenway versus the Stadium because they couldn’t make the necessary adjustments when they played in New York. So the Yankees would pitch around Ted Williams a lot at the House That Ruth Built. And, as much as I loved Doerr and Stephens, they made lots of long outs there.

The Red Sox held a unique place in Hemond’s heart partly because the first major-league game he saw was at Fenway Park in 1938. His first favorite player was Jimmie Foxx, league MVP that year. Ted Williams later became his baseball idol, with two of Williams’s teammates—Doerr and Pesky—close behind. Notwithstanding what was then regarded as a long trip from Central Falls to Boston, he went to three or four games at Fenway every year. By contrast, before joining the Braves, in 1951, he had been to Braves Field a total of maybe six times.

The first time he saw the Braves in person was special, though, because it was

a Pawtucket Boys’ Club day where we went on the bus as a group to Braves Field. George “Highpockets” Kelly flipped a baseball to the top of the dugout that rolled to me. That made an impression—that the Braves coach wanted to give the ball to a fan, and I happened to be the lucky one to get it.

Not one to collect souvenirs, however, Hemond has no idea what happened to Kelly’s ball. “In those days you didn’t necessarily save the balls; you played with them.”

A couple of other times I sat in the right-field Jury Box. Devoted fans of Tommy Holmes were there on a regular basis. I remember Lolly Hopkins; she was from Providence and I used to see her, decked out and with her megaphone, rooting for the Braves, always seated behind their third-base dugout, like a fixture. It wasn’t too difficult to get a good seat, and you could move around and get a better seat as the game progressed. There were too many empty seats, unfortunately, and that’s what led to the Braves moving to Milwaukee. To me, Braves Field had the appearance of an old ballpark, even then. It was like turning back the clock. At that time, I guess it would have been hard for me to imagine it compared with the other major-league parks of the day, but, as you reflect, Braves Field looked like it was in its final stages. It didn’t have much appeal. And the wind blowing in off the Charles River affected the hitters. A lot of times you were disappointed with the long fly ball that you thought might go out, but they seemed to stay in too much for the Braves.

There was more glamour and excitement at Fenway because the crowds were better, with Williams and Doerr and those guys being real attractions. I don’t remember as many spectacular plays at Braves Field as they would have at Fenway. Sam Jethroe suffered some misadventures covering center field because of the wind at the Wigwam, and the arc lights—which I’m sure weren’t as strong as today—hadn’t taken hold yet when games began at twilight. While at Fenway, Dom DiMaggio never seemed to misjudge a fly ball. He could really roam and play shallow and go to the deep parts of Fenway and make excellent plays everywhere.

Always a student of the game, Hemond had this analysis about ballplayers’ gloves.

Today the equipment is different, so there are more diving plays than they made then. A real good running catch by Dominic was applauded and considered like a diving play today. The gloves weren’t as large to make those diving plays, so if they dove it probably didn’t stick in the glove after they had made this gallant attempt. So the players held their feet more often and made shoestring catches without somersaulting or diving. You could see the evolution of the game, the size of the athletes as well—not that they would not have had the ability to do what they’re doing today in defensive plays, but they didn’t have the equipment.

The one game during the 1948 season that stands out the most is when the Red Sox lost that playoff game against Cleveland, 8—3, and by the third or fourth inning Lou Boudreau—who had a big day—and Ken Keltner knocked in a bunch of runs. Gene Bearden pitched a very fine game. Denny Galehouse started for the Sox, which provoked controversy and a lot of second-guessing. The joke was they had picked the wrong man. Even though he was the team’s top pitcher that year, Mel Parnell had been used a lot down the stretch and would have had to come back on two days’ rest. Besides, Joe McCarthy, Hall of Fame manager from the Yankees, certainly had his reasons for doing it. Bernard Hogan, who was a warrant officer [in the Coast Guard] heading the finance department, let me listen to the game while working in my office that afternoon in Brooklyn. He knew I was kind of devastated when the Indians just won handily that day, with no contest. All of us in New England were heartbroken with the end result of it, because we were hoping for an all-Boston World Series.

I have some fine recollections of the Braves because I was rooting for them as well. Bob Elliott was the prominent player. Acquired from the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1947 [he was acquired in 1946 but would not debut with the team until 1947], he was known as “Mr. Team.” They put that tag on him and he won the league’s MVP award that year, as he stood out as the big run producer, power hitter, and RBI man and played very well at third, too. Elliott easily could have been named MVP again in 1948, for he carried the Braves on his shoulders that season with both his offensive and defensive ability. He had an outstanding year. Outfielder Jeff Heath was purchased from the St. Louis Browns and had a real productive year. It was unfortunate that he broke his ankle the last weekend of the season, sliding into home plate against Brooklyn after the National League pennant had been clinched. The Braves could have used his big bat in the World Series. Johnny Sain, Warren Spahn, and Vern Bickford did fine jobs. Lost among the feature stories was Nelson Potter. He had come from the Philadelphia Athletics at pretty much the tail end of his career and had some real clutch relief pitching performances for the ballclub.

When asked whom he would have cheered for had Boston’s teams met in the fall classic, Hemond made his allegiance perfectly clear. “I would have been rooting for the Red Sox. I was more of a Red Sox fan. There’s no doubt about that.”

In later years Hemond became good friends with several members of the 1948 National League championship team—Spahn, Sain, Holmes, Sibby Sisti, Earl Torgeson, and Tommie Ferguson (batboy). No Braves player ever voiced to him any preference for an allBoston World Series. Nor does he have recollection of anyone saying they were rooting for the Red Sox to lose to the Indians. “I never heard them say like, boy, we despised the other club. I don’t think they had that kind of rivalry or intensity.”

The top hitter among all regulars in the pitching dominant 1948 World Series was Torgeson—7 for 18, good for a .389 average. The Braves’ first baseman had other abilities that he put to good use on and off the field. “Earl liked to fight,” Hemond noted.

There was one [game]—it had to be in 1952, because I was there—and I was rooting for the Braves and Torgy got a base hit. Sal Yvars was the catcher for the New York Giants. He evidently didn’t like Torgeson and vice versa. So when Torgeson had circled the bases and scored a run, he got back to the dugout and someone said, “Yvars broke your bat over home plate after you got that hit.” And I remember Earl taking his eyeglasses off and putting them on the top step of the dugout, and he’s charging across the field and Yvars is taking off his equipment for that break in the inning. Bickford was just a couple of steps behind Torgy and all of a sudden Yvars looked up and Torgy pounded him. Knocked him all over off the second step of the Giants dugout. He was getting even for the broken bat. That was Earl. A real character.

As many baseball personnel know firsthand, Hemond’s passion for the game has never left him and probably never will.

By having a passion for it, you have more recollections of things that happened because you lived them for the moment vividly and stored them in your memory bank. Whatever people do in any walk of life, if they don’t have a passion for what they’re doing, then they lack the memories, because they didn’t appreciate or live the moment with excitement and enthusiasm. That’s why every day is an adventure if you make it such, and you can make it more if you make it such. I can’t help but smile when I’m talking with you because of all the pleasurable moments that you enjoy in being part of something that means so much to you, and you find that it means a lot to so many people who follow baseball, and you feel sorry for those who have not had the opportunity to enjoy it as I have and to have lived and met the people that I admired from afar as a fan, and then all of a sudden you find yourself knowing them as human beings and great people.

MORT BLOOMBERG, a SABR member for more than thirty years, has a doctorate in psychology, writes baseball articles that he vows always will include mention of his favorite team, the Boston Braves, and “runs” sausage races for the Milwaukee Brewers during spring training.