The Night Elrod Hendricks Pitched

This article was written by Norman Macht

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 27, 2007)

If Earl Weaver’s retirement repose is ever disturbed by nightmares, chances are a recurring one bears the dateline: Toronto – June 26, 1978.

If Earl Weaver’s retirement repose is ever disturbed by nightmares, chances are a recurring one bears the dateline: Toronto – June 26, 1978.

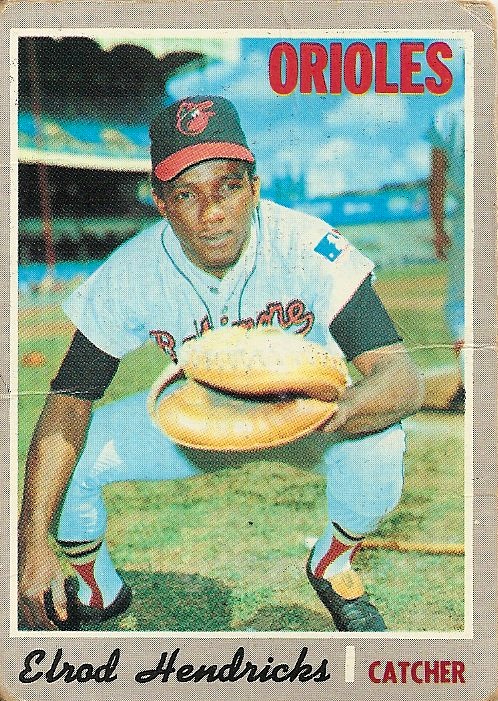

That night the fledgling Blue Jays, losers of 102 games in their second year of existence, handed Weaver the most humiliating loss of his career. The 24-10 rout also inscribed the late Orioles bullpen catcher Elrod Hendricks and outfielder Larry Harlow in the pitching ledgers of the record books.

Playing before 16,184 in Exhibition Stadium on a balmy Monday night, Weaver confidently sent southpaw Mike Flanagan (11-4) to the mound against the last-place Blue Jays, who had won 22 and lost 47.

Eddie Murray doubled Rich Dauer to third in the top of the first and Lee May’s single gave the O’s a quick 1-0 lead off lefty Tom Underwood. In the bottom of the first Flanagan fanned leadoff batter Willie Upshaw, which must have made the superstitious Weaver squirm, for it is common knowledge among those attuned to the baseball occult that striking out the first batter of the game is an omen of ill tidings to follow.

It didn’t take long for the tide to turn. Flanagan faced six in the second and retired none. By the time reliever Joe Kerrigan could stop the flood, nine runs had scored. The Birds scratched back with one in the third, but Kerrigan was roughed up for four runs on five hits in the last of the third before Tippy Martinez bailed him out.

Down 13-2 after three, the O’s battled back with three in the fourth, but Martinez continued to throw batting practice for the Jays. It was man overboard for Tippy, who gave up six runs on five hits and two walks.

With the score 19-6 in the fifth, Weaver contemplated his rapidly depleting bullpen, the need for at least two rested arms to pitch a doubleheader in Toronto the next day, and the relative merits of a different line of work.

Meanwhile, to make sure there would be at least one survivor, bullpen catcher Elrod Hendricks had sent closer Don Stanhouse to the clubhouse, reasoning that if Earl saw him, he would use him. When Earl saw nobody in the bullpen but Elrod, he looked behind him in the dugout and saw his regular center fielder, Larry Harlow. Benched against a left-handed starter, Harlow hadn’t pitched since his rookie pro-season at Key West in the Florida State League.

Weaver asked if he would go in and pitch. Harlow said okay. He walked out to the mound and began warming up with catcher Rick Dempsey, while Toronto manager Roy Hartsfield engaged in a discussion with the quartet of umpires over how many warmup pitches are allowed for an outfielder coming off the bench to pitch. By the time the matter was peaceably resolved, Harlow’s left arm was limber.

Weaver looked like a genius when Harlow disposed of catcher Brian Milner (a .444 lifetime hitter in two games) on a groundball to second, and struck out Upshaw. Up stepped Bob Bailor, who had been Harlow’s roommate for a half dozen years in the Baltimore organization. Bailor laughed as he stepped in to bat against his old roomie. Whether there is any connection between that outburst of hilarity and what happened next is left to the psychobabblists to unravel.

Bailor walked. Howell walked. With Rico Carty at the plate, Harlow threw a wild pitch that advanced the runners. A minute later he wished he’d thrown another one. Carty almost took his leg off with a line drive.

“I thought [shortstop] Kiko Garcia would get it,” Harlow said. “When he didn’t, I knew I was in trouble.”

He was right. He walked Otto Velez, and John Mayberry hit a grand slam. The score was 24-6.

While Harlow was handing out his fourth free pass of the inning, to Dave McKay, Earl Weaver was on the phone to the bullpen.

“Can you throw strikes?” he said.

Elrod looked around him; there were no pitchers in the bullpen.

“You know you’re speaking to Elrod,” he said.

“I’m fully aware of that,” Earl said. “Can you throw strikes?”

“Sure, I can throw strikes,” Elrod said, still wondering why Earl was asking the question.

“How long will it take you to get loose?” “For what?”

Weaver said, “As soon as you can get loose, I’m gonna put you in the ball game.”

“Well,” Elrod said, “I warmed up all the pitchers who went into the game. I threw 40 minutes early hitting this afternoon. I like to think I’m pretty loose, as loose as I’m going to get.”

“You’re in the ball game,” Weaver said, then hung up and walked to the mound.

“I knew Weaver was mad at me when he came out,” Harlow recalled. “I told him it was tough to throw strikes when it was so long since the last time I pitched. He was pretty disgusted.”

Elrod stood in the bullpen with his catchers’ mitt and coaching shoes. “You gotta be kidding,” he said to himself as he started “the longest walk of my life. On the way in I was thinking, ‘What’s the major league record for runs scored in a game?’ I knew that after I got out there, unless I got hit with a line drive, they would break the record. I couldn’t pitch with a catcher’s mitt so Jim Palmer came out and threw me his glove and yelled, ‘Hold ’em there, Rex.’ The pitchers used to call each other Rex.

“It was scary. I had never been out there without a screen in front of me for batting practice.”

Elrod told Dempsey there was no need to put down any signs. “Everything was going to be straightforward, slower even than B.P. I didn’t try to mix them up; there was nothing to mix.”

He had so much “stuff” on his first few throws, the ball kept popping out of Dempsey’s mitt. Dempsey took out his chewing gum and stuck it on the ball.

“He was having more fun out of it than I was,” Hendricks said. “It was probably a joke to everybody else but Earl. He didn’t think it was funny.”

Rico Carty was standing near the dugout laughing. Elrod yelled at him, “If you or that big guy at the plate [Tim Johnson] hit one back at me, I’m going to come after one of you. You hit it too hard. I’m going to throw inside. You pull the ball.” He was more concerned with survival than his earned run average.

Johnson hit what looked like a rocket right back at him. Elrod flinched and got out of the way. “But it was really an easy three-hopper I could have barehanded,” he later recalled.

He got Milner on a fly ball to end the inning. He pitched 2.1 innings and retired with a career ERA of 0.00.

“I was surprised that I did as well as I did,” he said later, “but they were probably tired by the time I got there.”

Stanhouse volunteered to pitch the eighth to get some work.

“Nice going, way to go,” Weaver told Hendricks. But he never asked Elrod to pitch again.

The Orioles scored three in the seventh and one in the eighth to pull within 14. That’s how it ended, 24-10. The Blue Jays had 24 hits and eight walks. At least the Orioles made no errors, except for showing up that night.

NORMAN MACHT’s biography of Connie Mack (through 1914) was published in July. Now a resident of San Marcos, Texas, he has begun writing “the rest of the story,” which he hopes will not take another 22 years.

Author’s Note

This is slightly revised from its appearance July 22, 1994, in the now-defunct Orioles Gazette.