August 1921: New York Giants sweep the Pirates in a crucial 5-game series

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in 2021 as part of the SABR Century 1921 Project.

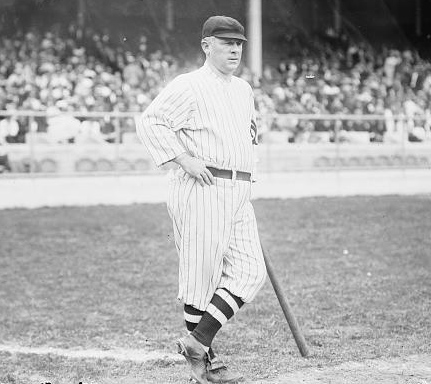

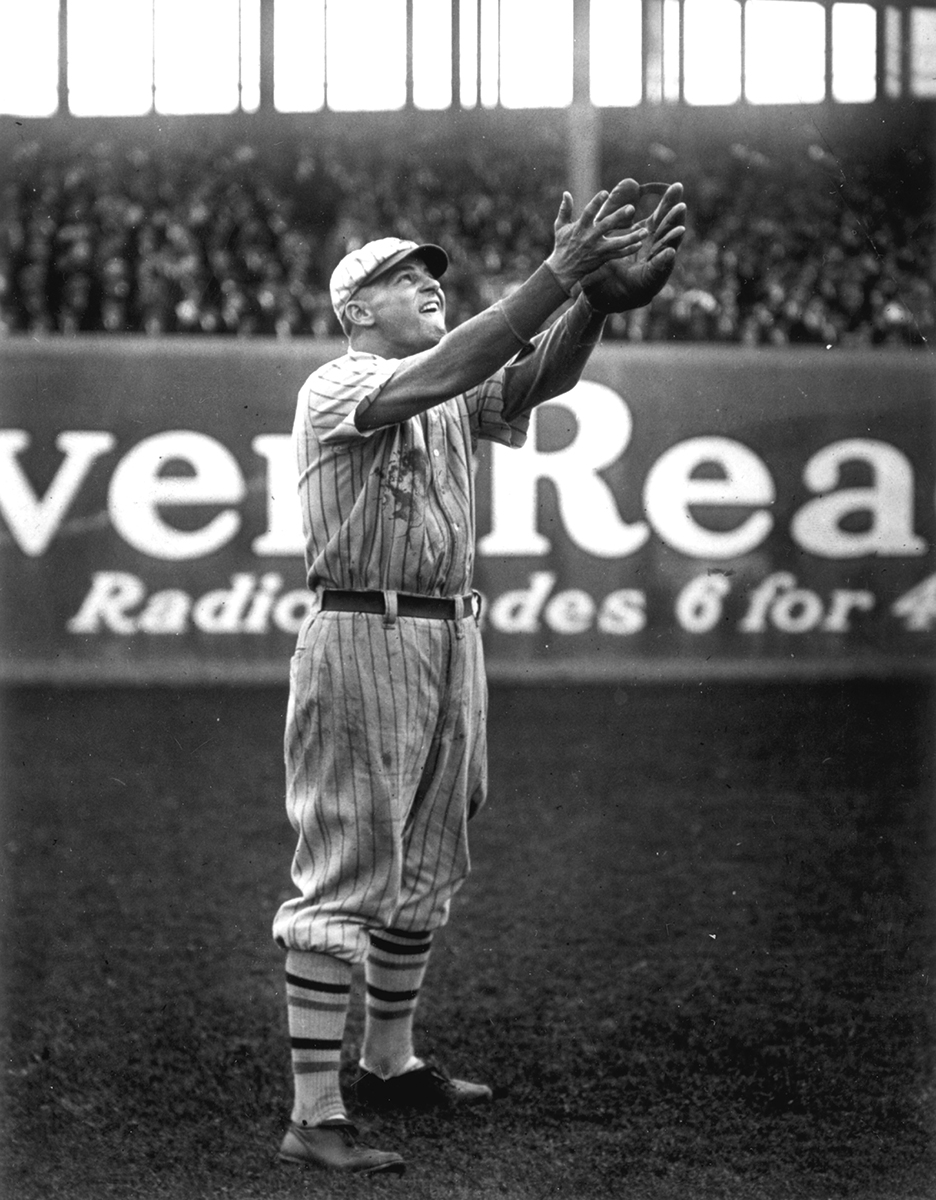

1921 New York Giants team photo (SABR-RUCKER ARCHIVE)

On the morning of July 31, 1921, the New York Giants and the Pittsburgh Pirates were tied for first place in the National League, each with a record of 60-35. The teams had eight games remaining between them – five at New York’s Polo Grounds in late August and three at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field in mid-September. Those games figured to be the major factor in deciding the National League pennant winner.

However, much had changed in the fortunes of both teams before the August 24 doubleheader that opened the five-game series in New York; so much so that the series at the Polo Grounds now appeared likely to be simply a coronation for the Pirates. Since July 30, manager George Gibson’s Pirates had won 16 of 22, while John McGraw’s stumbling Giants had lost 15 of 25. Pittsburgh held a 7½-game lead over the Giants, their largest of the season, and one many in the press thought close to insurmountable.

The Giants had won 9 of the 14 games already played between the two teams this season, which now meant nothing. They had to win all five games to get back in the race. The teams would play a doubleheader on Wednesday, August 24, and single games on each of the next three days.

While discussing the Pirates pitching staff, sportswriter Walter Trumbull wrote: “If the Pittsburgh team gets into the world’s series, and there appears to be small doubt that it will, it will be interesting to watch the work of the veteran and the youngster.”1

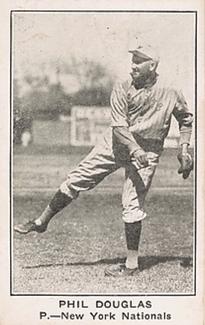

The “youngster” was Whitey Glazner, a rookie who would go 14-5 for the season. The “veteran” was Babe Adams (12-3), who would pitch the opening game of the doubleheader. Wilbur Cooper (20-8), the league’s top winner at this date, would be Gibson’s starter in the second game. John McGraw would counter with Art Nehf (14-8) and Phil Douglas (10-8). The Pirates arrived in New York supremely confident that the city of Pittsburgh would be returning to the World Series for the first time in 12 years. Owner Barney Dreyfuss had even begun the process of adding more bleacher and grandstand seats to Forbes Field for the World Series games he expected to host.

Dreyfuss’s longtime antagonist, Giants manager John McGraw, was in a much different situation. McGraw’s floundering team appeared on the verge of completing its fourth consecutive season without a pennant. The New York press that had mostly fawned on him for so many years now seemed more interested in the exploits of Yankee slugger Babe Ruth. Moreover, McGraw had begun hearing criticism from the fans and from certain segments of the press that it was he who was mainly responsible for the Giants’ poor play. Even some of his players had been complaining about his managerial style. Though he was still in uniform, McGraw had taken to running the club from the bench, with Hughie Jennings replacing him as the third-base coach. Some players disagreed with the move. Hugh Fullerton wrote, “Some of the Giants think McGraw ought to be on the coaching lines actively directing the club.”2

McGraw, in turn, was unhappy with the way his team had been playing. Inspired by his displeasure, he prepared his players for the season’s biggest series in his own inimitable way. Following a 10-7 loss to St. Louis, the day before the opening of the Pittsburgh series, McGraw called a team meeting, at which he unleashed a brutal tirade directed against his players. He told them that despite having the potential to be one of the best clubs he had ever managed, they were now becoming one of the worst. Pointing to the success of the pennant-contending Yankees in the American League, he said that a Giants-Yankees World Series would put a lot of money in all their pockets.

McGraw, in turn, was unhappy with the way his team had been playing. Inspired by his displeasure, he prepared his players for the season’s biggest series in his own inimitable way. Following a 10-7 loss to St. Louis, the day before the opening of the Pittsburgh series, McGraw called a team meeting, at which he unleashed a brutal tirade directed against his players. He told them that despite having the potential to be one of the best clubs he had ever managed, they were now becoming one of the worst. Pointing to the success of the pennant-contending Yankees in the American League, he said that a Giants-Yankees World Series would put a lot of money in all their pockets.

“Now it’s gone,” he screamed. “Gone because you’re all a bunch of knuckle-headed fools! Pittsburgh is going to come in here tomorrow laughing at us. Pittsburgh is going to take it all! Pittsburgh! A bunch of banjo-playing, wisecracking humpty-dumpties! You’ve thrown it all away! You haven’t got a chance! And you’ve got only yourselves to blame!”3

The next day while his players sat quietly on the bench watching the Pirates laughing and joking their way through batting and fielding practice before the first game of the doubleheader, McGraw stood quietly in a corner of the dugout. First baseman Charlie Grimm, one of the “banjo-playing, wisecracking humpty-dumpties” McGraw had referred to, sat in the Pittsburgh dugout strumming his ukulele.4 Then, in what seemed a show of disdain toward McGraw and his players, Pirates manager George Gibson ordered all his men to gather for team pictures to be used for the 1921 World Series program. The gesture by Gibson, who had coached under McGraw in 1918-19, also upset one of his own star players, Rabbit Maranville. “Pictures for what?” said the Pirates’ veteran shortstop. “Wait until we win the pennant before we have our pictures taken.”5

Maranville had been a major contributor to the Pirates’ success, both on defense, which they had expected, and on offense, which they had not. He was having the best offensive season of his 10-year career, batting .318, far above his previous high of .267 for the 1919 Boston Braves. Maranville opened the first game by lining a Nehf pitch for a double off the glove of leaping third baseman Frankie Frisch. He eventually scored the first run of the series on a sacrifice fly by Max Carey.

The Nehf-Adams matchup figured to be an excellent one. Nehf had beaten the Pirates four times this season, without a loss. However, Adams had been tough on the Giants too, and he had been pitching very well of late. Runs figured to be hard to come by, so when Irish Meusel smacked a two-run home run in the second, the largest weekday crowd thus far this season rose to its feet to cheer. It was Meusel’s 13th home run of the season, but his first as a Giant since coming over in a very fortuitous July 25 trade with the Phillies.

Nehf allowed another run, in the fifth, reducing New York’s lead to 3-2, but that would be all the Pirates would get. Adams left after the seventh trailing 6-2, before the Giants jumped on Glazner for four eighth-inning runs, to make the final score 10-2. Nehf’s five-hitter raised his record to 15-8, and 5-0 against Pittsburgh. He had been the last pitcher to defeat Adams, back on May 24, and in doing it again, he ended Adams’s nine-game winning-streak.

The second game was much like the first. It too was a low-scoring affair until the Giants broke it open with a big inning, this time a five-run sixth. Phil Douglas was even more effective in the nightcap than Nehf had been in the opener. Making great use of his best pitch, the spitball, he tossed a five-hit, 7-0 shutout. Giants catcher Frank Snyder, who spent 16 seasons in the National League, called Douglas “the best right-handed pitcher I ever caught.”6

Wilbur Cooper matched Douglas’s shutout pitching through four innings, before the Giants pushed across a run in the fifth. George Burns had the big blow an inning later. His three-run inside-the-park home run gave him four runs batted in for the game. Meusel’s fifth hit of the afternoon, a triple in the eighth, drove home the final run. Meusel had begun the day batting a measly .231 since joining the Giants. But beginning with this afternoon’s magnificent performance against the Pirates, and carrying through until the season ended, he was the offensive force the Giants had hoped for when they got him from Philadelphia. He batted .421, to raise his average as a Giant to .329, and his combined average to .343, the fourth highest in the National League.

The New York fans headed for the exits buoyed by the two wins. Their heroes had taken two full games off the Pirates’ lead, cutting it to 5½ games. If they could win the next three, or even two of the three, they would be back in the pennant race. And for those who dreamed of the first all-New York World Series, there was more good news. The Yankees’ 3-2 win at Cleveland had moved them into first place in the American League, a half-game ahead of the Indians.

The New York fans headed for the exits buoyed by the two wins. Their heroes had taken two full games off the Pirates’ lead, cutting it to 5½ games. If they could win the next three, or even two of the three, they would be back in the pennant race. And for those who dreamed of the first all-New York World Series, there was more good news. The Yankees’ 3-2 win at Cleveland had moved them into first place in the American League, a half-game ahead of the Indians.

The Giants players were in the clubhouse after the sweep, celebrating their refutation of McGraw’s words with their deeds, when the manager walked in. “I told you fellows last night that you didn’t have a chance,” he said. “Well, I was wrong. You have a chance, a bare chance. … if my brains hold out.”7 Recalling the incident years later, George Kelly said, “It’s a good thing he got out then or he might have been skulled by a shower of bats.”8

Had the tongue-lashing McGraw inflicted on his players before the doubleheader played a part in the Giants’ turnaround? Perhaps it had resonated with Meusel, who had been underperforming and may have needed this kind of spark. Yet it is difficult to imagine that McGraw’s harangue had much effect on any of the other regulars, all of whom were veterans and knew how important this series was.

Sixty-three years later, Kelly, whose memory at age 88 may have dimmed, claimed he did not remember the speech. “We didn’t have that pep talk and all that kind of baloney,” he said. “That was a lot of baloney in my days. I never heard McGraw come out and get on a speech to fire people up. You had to come out there and be fired up to win the ball game.”9

As for the two pitchers, Nehf was a serious professional who did not need a “pep” talk, and Douglas, detesting McGraw as he did, probably paid no attention. Still, part of a manager’s role is to address his players en masse, either negatively and sarcastically, as McGraw had done, or positively, as Gibson did before the game the next day. “All right, we looked lousy yesterday and lost two games, but we’re still 5½ games in front and finishing the season at home,” said the usually easygoing Gibson in an attempt to cheer his players. “Now let’s go out there and win today.”10

Not content to trust in words alone, Gibson shook up his batting order. But the moves proved futile. Fred Toney held the revamped Pirates lineup to single runs in the fourth and ninth innings as the Giants won again, 5-2. Toney’s sixth consecutive win was his 15th of the season and again tied him with Nehf for the team lead. He also had the game’s biggest hit, a second-inning home run into the right-field upper deck that accounted for three of the Giants’ five runs against Pirates starter Johnny Morrison.

After defeating them three times in two days, the Giants players suspected that the strain of leading the race for so long was beginning to tell on the Pirates. “Let’s go get ’em while the getting’s good,” said reserve outfielder Casey Stengel.11 Moreover, that specter of doubt settling over the Pirates was now being echoed in the Pittsburgh newspapers, like this item in the Pittsburgh Press: “It had been confidently hoped that when the team arrived here that a couple of battles would settle the little matter of which is the best team in the National League beyond a doubt. But the doubt still lingers, in fact is more evident than for some time.”12

That doubt grew even stronger the next day when, despite an outstanding performance by Earl Hamilton, the Pirates lost again. Hamilton allowed only five hits, but ended up a 2-1 loser to Phil Douglas in a game that featured outstanding defensive plays for both sides. Douglas, pitching with one day’s rest, got out of more tight scrapes than Harry Houdini. This was only fitting, as Houdini, the world’s best-known escape artist, was among the Friday crowd of 18,000, above normal for a weekday.

Unlike the previous three games, won relatively easily by the Giants, this one was tense and nerve-wracking. Douglas allowed 10 hits, but only the one run, thanks to a sensational sixth-inning double play started by shortstop Dave Bancroft. The Giants had far more trouble with Hamilton than they had experienced with Adams, Cooper, or Morrison. Their two fourth-inning runs came on a one-out walk to Bancroft, a triple by Frisch (the game’s only extra-base hit) that sailed over Dave Robertson’s head in right-center, and Ross Youngs’ infield single.

McGraw had told his players after the doubleheader that they had a chance if his brains held out. In truth, his brains, or maybe more correctly his baseball instinct, were a big part of this 2-1 win. The pre-series plan was for Rosy Ryan to start this game, but Ryan had hurt his arm in his last outing, and he was unable to pitch. That left Jesse Barnes and Pat Shea. McGraw was reluctant to start either one: Barnes, because he had not pitched well recently, and Shea, who he felt was too inexperienced. But before he could make a decision, Phil Douglas spoke up. “Let me go in there this afternoon, and I’ll beat those fellows.”13 Aware that Douglas had already beaten Pittsburgh four times this season, McGraw played a hunch that he could do it again.

McGraw had told his players after the doubleheader that they had a chance if his brains held out. In truth, his brains, or maybe more correctly his baseball instinct, were a big part of this 2-1 win. The pre-series plan was for Rosy Ryan to start this game, but Ryan had hurt his arm in his last outing, and he was unable to pitch. That left Jesse Barnes and Pat Shea. McGraw was reluctant to start either one: Barnes, because he had not pitched well recently, and Shea, who he felt was too inexperienced. But before he could make a decision, Phil Douglas spoke up. “Let me go in there this afternoon, and I’ll beat those fellows.”13 Aware that Douglas had already beaten Pittsburgh four times this season, McGraw played a hunch that he could do it again.

Another version of the story had McGraw approaching Douglas in the clubhouse 30 minutes before game time and saying, “Douglas, you work.” “But Mac, I worked day before yesterday. Are you sure I can go in there and lick ’em again?” responded Douglas, clearly not as confident of victory in this version. “Phil, you work,” replied McGraw, ending the discussion.14

In whatever way McGraw came to choose Douglas, obviously he had made the right choice. Rabbit Maranville summed up the feelings of the Pirates players after their fifth loss to Douglas this season. “We have seen too much of The Shuffler,” Maranville grumbled. “There ought to be a law against a fellow as big and as smart as that having all that stuff.”15

For the fifth and final game of the series, McGraw came back with his ace, Art Nehf. With Pittsburgh’s lead now down to 3½ games, Gibson might have come back with Cooper or Adams on short rest, but evidently did not wish to show any sign of panic to his players. Instead, he chose Hal Carlson, a spot starter with a 2-4 record this season. Yet, it was unlikely that Carlson, a veteran of the Battle of the Argonne Forest, would feel any undue pressure in pitching a baseball game.

Changes in momentum are often subtle and cannot be measured, but the 36,000 at the Polo Grounds that Saturday had a sense that it had shifted sharply in favor of the Giants.16 That sense was correct and was reinforced that afternoon, when Nehf, who had pitched a five-hitter in the first game of the series, pitched a four-hitter in this one. Supported by a large, enthusiastic crowd, whose deafening roars lent a World Series-like atmosphere to the game, the Giants came away with a 3-1 victory and a stunning sweep of the five-game series. Nehf’s win raised his record against Pittsburgh to 6-0, the only such record by any pitcher against any team in the National League at that point in the season.

Giants pitching, suspect for much of the season, was spectacular throughout this series. Nehf and Douglas, twice each, and Toney had thrown five complete games and allowed the league-leading Pirates only six runs. In beating the Pirates for the eighth consecutive time, the Giants raised their season’s record against them to 14-5. Pittsburgh’s lead, which had been 7½ games on August 23, was now just 2½ games on August 27. “Not bad,” said McGraw after the sweep. “But Pittsburgh is still in first place.”17

It remained to be seen how much psychological damage the Giants had inflicted on the Pirates in these five games. And the numbers still favored the Pirates. With a record of 76-46, they still had four fewer losses than the 75-50 Giants. That meant the Giants would need Pittsburgh to lose five more games than they would over the remaining month of the season to finish first. As New York sportswriter Arthur Robinson reminded his readers after the sweep, “Take nothing for granted in baseball.”18

New York’s spectacular comeback and Pittsburgh’s woeful collapse were not without repercussions. Manager Gibson’s defense of his team, and of himself, had not satisfied Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss, who blamed the downfall on having too many fun-loving spirits on the club. Dreyfuss was furious that his team had allowed itself to be humiliated by McGraw and the Giants. The enmity between the two men had an extensive history. In one memorable incident during a game at the Polo Grounds, back in May 1904, McGraw had shouted such gross obscenities at Dreyfuss that the Pirates’ owner felt compelled to report it to National League President Harry Pulliam. In June of that year, Pittsburgh fans attacked the Giants players as they returned to their hotel from Exposition Park, the Pirates’ home field.

Now, 17 years later, the mutual distrust between the two teams was as great as ever. Charges had surfaced that the Pirates had somehow been drugged during their late August series in New York. A Sporting News editorial discussed the rumor that friends of McGraw had enticed Pirates players to speakeasies during their visit to the big city and plied them with alcohol. Yet that very column noted that there was little substance to the report, as was also the case with the drugging story.19

Several years later, Pittsburgh sportswriter Ralph S. Davis blamed what he called “the joy riding Bucs of that year” for the loss of the pennant. “It was a failure of Dreyfuss’ athletes to tread the straight and narrow pathway and keep themselves in playing condition,” Davis wrote. “Joy rides were numerous, and the Pirates were a dandy bunch of .500 hitters in the Midnight League,” he added. “On the other hand, the eyes that shone brightest at night were sometimes dim in the afternoon, and rival pitchers had little difficulty in putting over the fooler on Pittsburgh batters.”20

Dreyfuss would later say, “After the Pirates lost those five games in a row, there were rumors that something was wrong. It is generally understood that some of the Pittsburgh players broke training rules at that time and their actions in a large part were blamed for the collapse of the team and the loss of the pennant.”21

A much more serious allegation had appeared late in the 1921 season. An article appeared in the September 3, 1921, issue of Henry Ford’s anti-Semitic newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, entitled “Jewish Gamblers Corrupt American Baseball.” The Independent had been blaming all of America’s and the world’s problems on the Jews, and this time it was baseball’s turn. Painting with a broad brush, and including everyone with a Jewish-sounding name connected to baseball in any way, the article claimed that Jewish gamblers and Jewish owners had corrupted the game. In doing so, it made no distinction between a known gambler, such as Arnold Rothstein, and a respected owner, such as Barney Dreyfuss.

From that, the story evolved into the Jewish owner, Dreyfuss, having his team deliberately lose the pennant to the Giants in exchange for money from Jewish gambling interests. But even the Sporting News, whose own editorial page was not immune from anti-Semitic remarks, balked at this allegation.22 Under a headline that read “Pirates Were Just Not of High Class,” it editorialized, “The stuff is ridiculous on the face of it, and none but the most evil mind could imagine, none but the most perverted sporting editor give space to such guff.”23

Notes

1 Walter Trumbull, “The Listening Post,” New York Herald, August 24, 1921: 12.

2 Hugh S. Fullerton, “On the Screen of Sport,” Evening Mail (New York), August 27, 1921.

3 Noel Hynd, The Giants of the Polo Grounds (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 222.

4 Hynd, 222.

5 Walter “Rabbit” Maranville, Run, Rabbit, Run (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2011), 48.

6 John Lardner, “That Was Baseball: The Crime of Shufflin’ Phil Douglas” New Yorker, May 12, 1956, 142.

7 Hynd, 222.

8 Hynd, 222.

9 From an April 10, 1984, interview Kelly did with Norman Macht, chairman of the Society for American Baseball Research’s Oral History Committee.

10 Fred Lieb, The Pittsburgh Pirates (New York: G.P. Putnam’s, 1948), 190.

11 Arthur Robinson, “McGraw Men Close to Leaders,” New York American, August 26, 1921.

12 “Hamilton Hope in Fourth Game,” Pittsburgh Press, August 26, 1921: 24.

13 Daniel, “Douglas Returns to Beat Pirates,” New York Herald, August 27, 1921.

14 Arthur Robinson, “‘Shufflin’ Phil Turns Trick; Works After Only a Day’s Rest,” New York American, August 27, 1921.

15 Tom Clark, One Last Round for the Shuffler (New York: Truck Books, 1979), 51.

16 For the second time at a Giants’ home game this year, it was necessary to lift the screens in center field to allow for more patrons.

17 Hynd, 223.

18 Arthur Robinson, New York American, August 28, 1921.

19 “In Earnest, at Any Rate,” The Sporting News, September 29, 1921: 4.

20 Ralph S. Davis, “Pirates Refused to Bear Down in 1921,” The Sporting News, January 13, 1927: 6.

21 “Giants and Robins Named in Scandal,” New York Times, January 4, 1927: 1.

22 A relatively recent example was the weekly’s coverage of the Black Sox Scandal, as noted in Daniel A. Nathan, Saying It’s So: A Cultural History of the Black Sox (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2005), 32-36.

23 “Pirates Were Just Not of High Class,” The Sporting News, December 8, 1921: 5.