Risqué Business

This article was written by Richard McBane

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State (Atlanta, 2010)

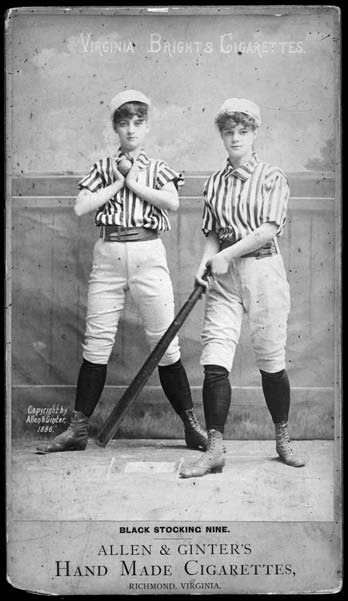

For about two weeks in July 1886, crowds gathered around a window on the Pryor Street side of the Kimball House in downtown Atlanta. The attraction was a set of cigarette-advertising cards that purported to represent what the Atlanta Constitution called “nine handsome female baseball players in attitudes common in that popular game.”1

According to the Constitution, “it has been a daily occurrence for crowds to gather around the window and gaze admiringly upon the graceful forms depicted by the photographer’s art. All sorts of people have been there, from the ragged boot black to the merchant prince.”

According to the Constitution, “it has been a daily occurrence for crowds to gather around the window and gaze admiringly upon the graceful forms depicted by the photographer’s art. All sorts of people have been there, from the ragged boot black to the merchant prince.”

A captain in the Atlanta police department examined the pictures but lodged no charges. The Constitution, however, was determined to make the most of this small sensation, reporting that “a number of staid citizens have expressed themselves as being opposed to the exhibition of the pictures, and have declared their intention to request Mayor Hillyer to interfere. It is claimed by these citizens that the pictures are indecent.”

The Constitution also reported that New York City newspapers, aided by Anthony Comstock, an agent for the Society for the Suppression of Vice, had joined in a crusade in that city against the photographs, while the cigarette dealers responded that the pictures were no more immoral or indecent than the pictures of wellknown actresses exhibited in the bars of leading hotels. Atlanta cigarette dealers followed the same line of argument, declaring that “several of the Atlanta photographers exhibit pictures similar to those of the female baseball players, and that if the latter should be suppressed, so should the former.”

The Constitution also reported that an unidentified but prominent lawyer from a Georgia community had attempted to buy a set of the pictures. When he was told that they were not for sale but were given to tobacco dealers to be used as advertisements, he represented himself as a tobacco dealer who wanted a few sets for advertising purposes. “All right,” said the agent, “buy five or ten thousand cigarettes and I’ll give you half a dozen sets.” Away went the lawyer under a cloud.

That tale was but a puff of smoke compared to widely circulated rumors, again picked up from New York newspapers and repeated by the Constitution, that rich old bachelors who had sought out the girls (who had been portrayed in another set of advertisements as “cigarette makers” rather than female ball players) had suffered disappointments leading to suicides.

The Constitution reporter, at least, finished with a note of realism, writing: “For the benefit of the dudes, it may be said that the cigarette pictures in no instance represent real cigarette makers. They are all taken in New York, from young women specially employed to sit for them.” Or, in the case of the supposed female ball players, to stand for them.

RICHARD MCBANE, a retired newspaperman, is the author of “Glory Days: The Akron Yankees of the Middle Atlantic League, 1935–1941” (Summit County Historical Society, 1997), and “A Fine-Looking Lot of Ball Tossers: The Remarkable Akrons of 1881” (McFarland, 2005).

Notes

1 Atlanta Constitution, 16 July 1886, 7. This is the sole source for this account.