Working to Play, Playing to Work: The Northwest Georgia Textile League

This article was written by Heather S. Shores

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State (Atlanta, 2010)

Floyd County, Georgia, in the northwest corner of the state, once supported eight different textile mills, each with a baseball team composed of mill workers. These teams became the formally organized Northwest Georgia Textile League and flourished between the 1930s and 1950s, providing Floyd County with three decades of industrialized community recreation that has not been rivaled since.The popularity of baseball over the years has given rise to countless teams and leagues at all levels of society and in virtually every corner of the nation. One form of the game that developed in the United States by 1900 was industrial baseball.[fn]Benjamin G. Rader, American Sports: From the Age of Folk Games to the Age of Televised Sports (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1996), 62.[/fn] Historical evidence of company-sponsored baseball can be found in many areas of the country; however, in the early twentieth century it was in the textile-mill villages across the southeastern region of the United States that industrial baseball caught on and settled into the roots of the community. One area with strong ties to textile mill–sponsored baseball is Floyd County, Georgia, which lies in the northwest corner of the state, along the Alabama state line. A region saturated with baseball traditions, the Floyd County area at one time supported eight different textile mills, each with a baseball team composed of mill workers. These teams became the formally organized Northwest Georgia Textile League in 1931. This league reached its pinnacle of success during the years of the Great Depression before its demise in the 1950s, providing Floyd County with three decades of industrialized community recreation that has not been rivaled since. The Northwest Georgia Textile League both serves as an example of highly organized industrial baseball in the southeast and demonstrates how recreational activities such as baseball can become an integral part of the social structure of a community.

The origins of industrial baseball lie in the aftermath of the Civil War. In the decades following that conflict, Southern entrepreneurs, funded by Northern investors, sought to create a “New South” by transforming the existing agrarian economy into one grounded in industry and cash-crop capitalism. Beginning in the 1880s, industry in the South grew at an exponential rate, with textile mills as the keystone in the region’s industrial base.[fn]Douglas Flamming, Creating the Modern South: Millhands and Managers in Dalton, Georgia, 1884–1984 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992), xxvii; Pete Daniel, Standing at the Crossroads: Southern Life in the Twentieth Century (New York: Hill and Wang, 1986), 42.[/fn] To attract rural people to work, mill owners constructed mill villages soon after they established each business. These villages evolved into self-sustaining communities, providing workers with places to live, eat, and shop. As with the mill villages, the mill-sponsored baseball teams extended the influence of the company into the personal lives of the workers.

Historians offer two very different interpretations for the motives behind mill baseball. Many support the idea that company management created baseball teams in order to promote teamwork, to keep workers away from labor unions, and to teach immigrant workers how to be “real Americans.” In addition, these scholars argue that organized sports such as baseball helped workers fresh from the fields become more dependent on and accustomed to mill and village life as opposed to the often nomadic, seasonal schedule of the agrarian worker. These historians believe that mills organized baseball teams “in an effort to transform sandlot games into a sport sponsored by and identified with the company.” The same authors contend that baseball kept workers from being “idle” outside of business hours, encouraged them to stay at the mill for longer periods of employment, and, according to one manager from a South Carolina mill in 1910, taught employees from rural areas the “rules” of mill life.[fn]Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns, Baseball: An Illustrated History (New York: Knopf, 1994), 124; Daniel, Standing at the Crossroads, 42; Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, James Leloudis, Robert Korstad, Mary Murphy, Lu Ann Jones, and Christopher B. Daly, Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World (New York: Norton, 1987), 135–37.[/fn]

Other scholars argue that mill baseball was not an advantage for the company alone. They believe mill baseball was more worker oriented than some people have realized, at least for the players. Many mill baseball managers and players in South Carolina had the bargaining power to secure good financial support for the team each season. In Dalton, Georgia, players seemed to have more control over their situation in the mill, using their talents on the field to alter the “rules” of their lives off the field. For example, the best players enjoyed some opportunities for mobility within the mill network as different companies sought to recruit them from competitors.[fn]Thomas Perry, Textile League Baseball/South Carolina’s Mill Teams 1880– 1955 (Jefferson, Mo.: McFarland, 1993), 50; Flamming, Creating the Modern South, 163–64.[/fn]

While there is little debate that mill baseball teams in Floyd County were started in order to bond workers even more strongly with the company, by the time these teams were formed into an organized league in 1931, the players were able to exert some control over their relationship with the mill. Even with the economic stresses of the Great Depression, mill baseball players earned extra pay for their abilities on the field and could even be granted less arduous jobs in the mill.[fn]Beth Gibbons, Videotaped interview by Heather Bostwick, 19 September 2000, Special Collections Department, Rome–Floyd County Library, Rome, Ga.; Harry Boss, videotaped interview by Beth Gibbons, 1995, Special Collections Department, Rome–Floyd County Library, Rome, Ga.[/fn]

As an industrial area, Floyd County illustrates the traditional ideals that appear to be common to many areas that supported industrial teams because of the shared values that often emerged in mill communities. The situation in Floyd County closely mimics, in terms of structure and community function, the textile-mill baseball teams and communities in South Carolina described by Thomas Perry in Textile League Baseball: South Carolina’s Mill Teams, 1880–1955. However, certain factors—the unusually high concentration of teams in the area, the participation of those teams in an official league, and the fact that the region was considered the best in the country for fierce competition among industrial teams—made the Rome–Floyd County area of northwest Georgia an atypical but significant example of Southern industrial baseball. Thus, the community of Floyd County offers an excellent case study to examine the relationship between mill teams and the people they represented from the 1920s to the 1950s.[fn]Flamming, Creating the Modern South, 167. Douglas Flamming suggests that mill communities, because of the close proximity of the families and similar backgrounds of the workers, create their own system of values and social standards not unlike those of rural communities. At Crown Mill in Dalton, Georgia, some of these behavioral “rules” included no drinking and keeping both house and yard clean. Flamming asserts, however, that these social norms were by no means followed by everyone in the mill village but did serve as a set of basic guidelines for mill families to judge one another in the community. In many cases, this set of behavioral rules is reinforced by mill regulations as well. The mill villages of Floyd County created their own set of social rules not unlike those of Crown Mill in Dalton. Also, see Rhonda Sonnenburg, “When Textile Mill Athletes Were Champs,” Fiberarts 25, no. 5 (March/April 1999): 8.[/fn]

Floyd County’s long tradition of baseball laid a solid groundwork for the Northwest Georgia Textile League. By 1868, organized baseball was in full swing in the area, with early clubs like the “Constellation Base Ball Club” meeting other local teams for games in the city of Rome. In 1910, Rome became a charter member of the newly formed Southeastern League; the “Romans” (later the “Hillites”) played against teams from Gadsden, Alabama; Knoxville, Johnson City, and Morristown, Tennessee; and Asheville, North Carolina. That team folded along with the league during the 1912 season, but the city had professional baseball again in 1913 when the Morristown (Tennessee) Jobbers of the Class D Appalachian League relocated to Rome and became the “Romans.” That relationship was short-lived, as the team moved again after one season, but Rome switched over to the Georgia Alabama League (also Class D) in 1914 and maintained membership until the league folded early in the 1917 season, like many other minor leagues affected by manpower shortages, travel restrictions, and reduced fan interest brought on by World War I.[fn]Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, N.C.: Baseball America, 1993), 137.[/fn] During that final season, the team represented both Rome and nearby Lindale but retained the nickname Romans.

The area was without professional baseball for a few years, but in 1920 both Rome and Lindale became charter members of the Class D Georgia State League, which had been resurrected following two earlier incarnations (1906 and 1914). [EDITORS’ NOTE: The latter version of this league was a “continuation” of the Empire State League discussed elsewhere in this journal.] This time, the league and the two teams from the Rome area (and a team from Cedartown in neighboring Polk County) lasted for two years, but after the 1921 season, the area’s baseball fans once again had to rely on semiprofessional and amateur versions of the game.

Professional baseball returned to the area in 1928, when a revitalized Georgia–Alabama League fielded six teams from northeastern Alabama and northwest Georgia, including teams from Lindale and Cedartown—but not Rome, the area’s largest city. These teams testified to continued local interest in the sport, and when the league folded following the 1930 season, the crowds of spectators migrated to the Northwest Georgia Textile League.[fn]Rome (Ga.) News Tribune, 27 March 1868: 1, 19 May 1868: 19 July 1895: 4 July 1901: 1902 Industrial edition: 28 May 1912: 9 April, 4, 10–11 May, 7 June, 21 July 1910; Michael McCann, “Minor League Baseball,” Michael McCann Minor League Baseball History, www.geocities.com/big_bunko/total.htm, 2000; Polly Gammon, A History of Lindale (Rome, Ga.: The Art Department of Rome, 1997), 28–29; Baseball Reference, www.baseballreference.com.[/fn]

Over the years, various industries in the Floyd County area, from local divisions of well-known companies such as Coca-Cola to smaller institutions such as Battey Hospital, had sponsored baseball teams, but it was the textile mills that created the most organized and most popular teams. By 1900, the first textile mill–sponsored teams appeared in the Rome area, beginning a traditional mix of baseball and business that eventually culminated in the formation of the Northwest Georgia Textile League.

By 1931, many of the local mills had been established long enough to support fully organized athletic programs. With so many area mills sponsoring baseball teams and with professional ball no longer conveniently available for the fan base, organizers saw an opportunity and took advantage of it. The Northwest Georgia Textile League was born, and (after its original Opening Day was rained out) the six-team league began play on April 11. From then until August 28, 1954 (except for a three-year hiatus during World War II), textile-mill teams dominated the baseball scene in the northwestern corner of Georgia.[fn]Gammon, A History of Lindale, 28–29; Harry Boss, audiotaped interview by Rome Braves Historical Research Team, 14 February 2003, Rome Area History Museum, Rome, Ga.; Rome News Tribune, 18 June 1976.[/fn]

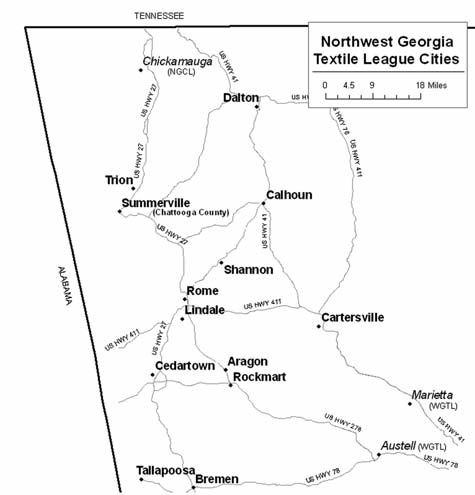

The six charter members of the league included the Tubize–Chatillion (Celanese) and Anchor Duck mills in Rome, Pepperell Mill in Lindale, and three Goodyear teams located in Rockmart, Cedartown, and Cartersville, the latter also being known as Atco Mill. Each team featured a roster of seventeen players, and the 30-game schedule was equally divided between home and away games all played on Saturdays. After that first year, Brighton Mills in Shannon, Georgia, which had reluctantly dropped out of the inaugural season to create a balanced six-team league, replaced Anchor Duck, and the league composition did not change for four years, until Aragon Mills joined in 1936, bringing membership to seven teams. The odd number of teams allowed each club to have an occasional “off weekend . . . to play games outside the league.”[fn]Rome News Tribune, 10 March 1936.[/fn] The opportunity for “outside” games was enhanced further by reducing the schedule from 50 [fn]In 1933, the league had authorized Sunday games and had expanded the schedule to 50 games.[/fn] games to 36. After two years, Anchor Duck returned, creating an eight-team league and a 42-game schedule for one year. When Aragon dropped out after the 1938 season, the league again had a 36-game schedule for seven teams, who stayed together for three years, until World War II. Chart 1 lists league membership over its entire life span; the accompanying map shows the proximity of the teams to each other.[fn]Klenc, Tom. Northwest Georgia Textile League (1931-1954): Research Guide, June, 2007. Unpublished document in Rome-Floyd County Public Library. Map courtesy of Magnolia SABR member Bill Ross.[/fn]

Over the years, NWGTL officials made a few other changes that affected the way the game was played. In 1935, the league eliminated the umpiring system that had hometown umpires travel with their teams and work games with a local umpire for the home team. Understandably, this system had generated criticism from fans and players alike. Under the new system, the league designated six umpires (each nominated by one of the league’s teams) who would work games in pairs but would never call a game in which their hometown team was involved. Since this system required that the umpires travel separately from the teams, their pay was doubled—to $4.00 per game. In 1938, the league introduced a mid-season All-Star Game, pitting the league-leading team against a team composed of the best players from the other league teams. The players split the gate receipts (after expenses were deducted), each earning some eight or nine dollars [fn]Rome News Tribune, 27 July, 1939.[/fn] in addition to the honor of being recognized as an elite player. Starting in 1939, the league used a Shaughnessy-style four-team playoff to select the league champion rather than a series between the champions of the first and second halves of the season.

Throughout these refinements, all teams in the textile league followed one ground rule: all players were white men employed by the mill. Starting in 1935, each team’s roster could include up to three young players whose parents worked for the mill that sponsored the team.[fn]Ibid., 31 March, 1935.[/fn] Jobs for players varied from mill to mill, the type of job depending upon which mill and mill manager the players worked under. In some cases, players like “Powerhouse” Jim Hammonds had intense jobs such as welding, working regular eight-hour shifts each day, with regular practice and occasional weekday afternoon games following work. However, it was not uncommon for the players to be assigned to lighter tasks on game days to make sure that they would be well rested for the game. The granddaughter of one industrial-league player remembers hearing her grandfather explain how his team would be given the task of painting a house in the mill village on game days, which really meant, according to her memories, “a day full of relaxation and plenty of beer.”[fn]Stacy McCain, ed. PastTimes: Hometown Heroes of the Playing Fields (Rome, Ga.: Rome News Publishing Company, 1996), 31; Hall et al., Like a Family, 135; Beth Gibbons interview, 19 September 2000.[/fn]

Textile-league players were compensated for their time on the field in addition to their regular salary. During the Depression era, players would make anywhere from $12 to $14 per week from their mill job, with an extra $4 to $7 per week for playing baseball. This extra pay added an incentive for mill workers to play well and make the team each year. These stipends also illustrate both the value placed on players by the mills and the dual strategies of both encouraging talent and imposing an economic control over the players in the league.[fn]Harry Boss interview, 14 February 2003; James C. McClanahan, audiotaped interview by Rome Braves Historical Research Team, 14 February 2003, Rome Area History Museum, Rome, Ga.; William Primm, Videotaped interview by Rome Braves Historical Research Team, 14 February 2003, Rome Area History Museum, Rome, Ga.[/fn]

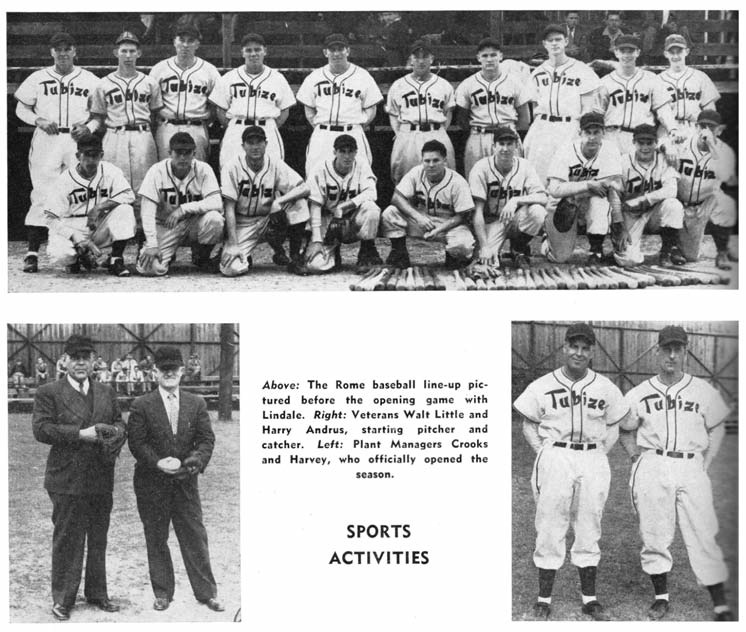

Textile-league events were literally at the center of the industrial communities and mill life in the Floyd County area. Initially games took place on Saturdays and Sundays, but once the Tubize Mill added lights at its park in 1938, night games during the week became fairly common. Games were not allowed to interfere with the work day, since production was the top priority for the mills. Scheduling games after working hours and on weekends ensured that workers would not be encouraged to shirk their job duties. Most mills had their own baseball fields, all located near the mill building itself, at the heart of the mill village. Many of these playing fields were large enough to support bleachers, full grandstands, and concessions and could be examples of community pride, as was the case with the Tubize Mill field, where mill workers raised funds for building materials and then supplied the labor themselves. Some of the mill fields were known for special characteristics such as trees in the outfield or a particularly deep center field that made it next to impossible for a ball to clear the fence. At least one field had a canvas fence built around it to keep fans who did not pay for a ticket from witnessing the game for free. The field at Anchor Duck Mill was known for having an outfield full of “cow patties,” since the land was also used for mill workers to graze their own livestock. Concessions such as popcorn and peanuts were sold at games, and many families would often bring picnic lunches to the ball park.[fn]Harry Boss interview, 1995; William Primm interview, 14 February 2003; Kenneth Forbus, letter to Heather Bostwick, personal collection of Heather Bostwick, Silver Creek, Georgia, 25 April 2001; Margaret Brannon, letter to Heather Fincher, Rome News Tribune archives, Rome, Ga., 2003; Tubize-Chatillion Mill, Tubize Yarns (April 1945): 12–13.[/fn]

Play was intense and rivalries ran deep in the Northwest Georgia Textile League. Each season culminated in a league championship, and winning it not only signified the athletic achievement of that team, but it also assured “bragging rights” for that particular mill community as a whole and secured the place of players on the winning team for the following season. Champions of the Northwest Georgia region would often go on to play industrial and minor-league teams from other states. On occasion, teams from the minor leagues, such as the Atlanta Crackers, or college teams from schools such as Oglethorpe University would come to Rome and play a textile-league team, offering fans another variety of play.[fn]Robert Gregory, “Diz”: The Story of Dizzy Dean and Baseball during the Great Depression (New York: Penguin Books, 1992),42; Harry Boss interview, 14 February 2003; Tubize-Chatillion Mill, Tubize Yarns (Rome, Georgia; March 1946); James C. McClanahan interview, 14 February 2003; Rome News Tribune (Rome, Georgia; 8 May 1940).[/fn]

Textile-league games could draw up to 2,000 or more fans per game during the regular season. It was not unusual for fans of both competing teams to fill the stands, paying 25 or 50 cents per game for adults and 10 cents for children. If seats were full, fans often sat along the baseline in order to see the game. Crowds that witnessed textile-league games appear to have been composed mostly of the textile workers, mill managers and supervisors, and their families, but citizens of the city of Rome, the heart of Floyd County, were also fans of the game. One local businessman, C. J. Wyatt, not only owned a store that sold sporting goods to the mills but also acted as league statistician for several years. It was common for the rural citizens of the county to attend the textile-league games, although exact numbers are not available.[fn]Harry Boss interview, 14 February 2003; William Primm interview, 14 February 2003; C. J. Wyatt, Personal communication with the author, 28 February 2003; Jackie P. Shores interview, 20 October 2000.[/fn]

There is no evidence, however, that the textileleague games drew or allowed any African American fans. Photographs of the stands during a game do not show an African American presence, and interviews with former players revealed no evidence that black citizens of Floyd County were regular attendees of the textile-league games. This does not mean that African Americans never attended the games, but the racial norms of the day would have prohibited black fans from entering into any social interaction with whites. It is more likely that African Americans in the area participated in their own recreational events. The later years of the Depression and the early 1940s saw the first vestiges of organized African American baseball teams in the area, perhaps as an offshoot of the successful professional Negro Leagues, which enjoyed their greatest success between the years 1933 and 1947. While not part of the Northwest Georgia Textile League, African American teams associated with industries and mills did exist in the Floyd County area, including the Black Giants from Tubize and the Fairbanks Eagles. These teams were not fully supported by the mills in the same manner as the white teams; the players were not paid for their efforts, but the mills often donated equipment and material to make uniforms, and photos and news stories would often be included in the mill newsletter.[fn]Harry Boss interview, 14 February 2003; William Primm interview, 14 February 2003; James C. McClanahan interview, 14 February 2003; Harold Bowman, audiotaped interview by Rome Braves Historical Research Team, 14 February 2003, Rome Area History Museum, Rome, Ga.; J. M. Culberson, audiotaped interview by Rome Braves Historical Research Team, 14 February 2003, Rome Area History Museum, Rome, Ga.; James “Slugger” Howren, audiotaped interview by Rome Braves Historical Research Team, 14 February 2003, Rome Area History Museum, Rome, Georgia; Robert Kinney, audiotaped interview by Rome Braves Historical Research Team, 14 February 2003, Rome Area History Museum, Rome, Ga.; Julius Locklear, audiotaped interview by Rome Braves Historical Research Team, 14 February 2003, Rome Area History Museum, Rome, Ga.; Hubert Stepp, audiotaped interview by Rome Braves Historical Research Team, 14 February 2003, Rome Area History Museum, Rome, Ga.; Elliz Z. Woods, audiotaped interview by Rome Braves Historical Research Team, 14 February 2003, Rome Area History Museum, Rome, Ga.; Nathaniel McClinic, Personal communication with Doug Hamil, 4 March 2003, Doug Hamil Advertising, Rome, Ga.; G. Edward White, Creating the National Pastime (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1996), 139.[/fn]

Fans who did not attend the games could still keep up with textile-league play. Games were broadcast on Rome radio station WLAQ, with announcer Lee Mowry behind the microphone. Announcing textile-league games was not easy; to call a game, Mowry would often take a taxi to the park, only to sit on the ground behind the umpire or on a rough platform fenced in by chicken wire. Well known by both players and fans, Mowry was not beyond the reach of pranksters on the field. Pitcher J. M. Culberson was known to throw warm-up pitches against the boards near Mowry’s head to “make sure he was awake.” Through thick and thin, Mowry stayed with the game. During one game between Brighton and Pepperell, Mowry broadcast for four hours and twenty minutes before the game was called because of darkness. Such was the fierce dedication of the players and the announcer to the textile-league games, the broadcasting of which shows how important the textile league and its games were to the communities surrounding Floyd County.[fn]Broadside (Rome, Ga.), 17 February 1977; Lee Mowry, personal communication with the author, 7 February 2003; McCain, PastTimes, 30, 34.[/fn]

In Floyd County, despite radio broadcasts of regional and national baseball, the textile-league teams remained the center of attention. Even in the mills with villages that provided amenities such as electricity and paid workers enough to be able to afford radios, local sporting events like industrial baseball games still held precedent over their national counterparts. “We paid attention when the World Series was on,” one man stated, “but the rest of the time local teams were more important.”[fn]Jackie P. Shores interview, 29 October 2000.[/fn]

Another method for keeping Floyd County fans in touch with the national baseball scene in a time before television was the “Playograph” that the City of Rome installed in the City Auditorium. This device was composed of a three-dimensional rendering of a baseball diamond, with individually moving pieces representing the players on a ballfield. When a play was made, a person controlling the device would move the corresponding pieces to represent what had happened during the game, while an “announcer” relayed a play-by-play commentary. Used primarily during the World Series, the excitement inspired by the mechanical action of the “Playograph” paled in comparison to the thrilling live games of local teams.[fn]Jackie P. Shores interview, 29 October 2000; McCain, 29.[/fn]

The press also emphasized local teams and provided another way that local citizens could keep up with the action in the Northwest Georgia Textile League. Industrial-league teams received prominent placement in the local newspaper, the Rome NewsTribune, garnering big headlines and even comic strips devoted to the games. National teams, on the other hand, were often given scant coverage in the press, even such prominent events as the opening celebration of the National Hall of Fame in 1939. In addition, the paper sponsored a local All-Star ballot that encouraged Floyd County residents to recognize their favorite industrial-league players. The annual league championship was also a highly publicized event for the area, its popularity placing it on the same level as the Dixie Series in the South and the Major League’s World Series.[fn]Rome News Tribune (Rome, Georgia), 11-13 June 1939: 30 June 1947: 6 September 1947.[/fn]

Practical matters may also have contributed to the popularity of the Northwest Georgia Textile League, particularly during the Depression era. A lack of transportation was one factor that kept people close to home. Baseball fans typically were limited to watching the games played in close proximity to their homes or workplaces, although it was not unheard of for a mill family to travel to Atlanta for a sporting event or entertainment. Before the Atlanta Braves existed, there were few professional baseball teams near northwest Georgia; Birmingham, Chattanooga, and Atlanta were the closest cities with minor-league teams. However, major-league teams including the Cincinnati Reds, Washington Senators, Cleveland Indians, and New York Giants played exhibition games at the Tubize Mill baseball field, giving Floyd County residents a chance to see national teams close to home.[fn]25. Tubize-Chatillion Mill, Tubize Yarns (Rome, Ga.) October 1946; Rome News Tribune (Rome, Ga.), 4 April 1940); Flamming, Creating the Modern South, 163; Sonnenburg, “When Textile Mill Athletes Were Champs,” 8; Gammon, A History of Lindale, 29.[/fn]

Textile-league games were popular not only because of the athletic spectacle they presented; they served other community functions, too. The nature and frequency of the ballgames gave Floyd County industrial communities a recreational activity through which they could pursue other social interests. Games were played in the heart of the mill village, offering employees a chance to visit with neighbors and friends, exchange local gossip, or court a favorite sweetheart. Games were important community occasions where the village could come together. The ladies dressed up, hoping to catch a player’s eye. “My grandmother and her sisters wouldn’t think of going to a game without dresses, hats, and gloves,” one woman remembers. “In that community, you only dated ball players.” Clearly, textile-league players enjoyed advantages beyond the extra cash.[fn]Hall et al., Like a Family, 139; Beth Gibbons interview, 19 September 2000.[/fn]

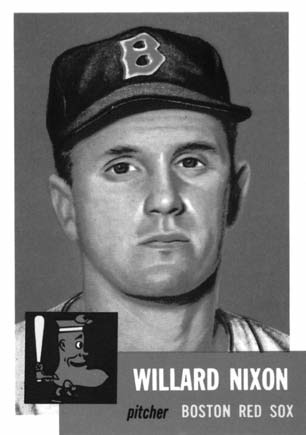

At the heart of every textile-league game were the players themselves. The fiercely competitive league fostered talented players and entertained northwest Georgia with a brand of baseball still remembered today. Most players came from the local area and ranged in age from eighteen to thirty-six, although mills would recruit college players to work and play for the company each summer. “College boys” were usually recruited from Southern schools such as Vanderbilt, Auburn, and Oglethorpe. Most of these players became aware of the Northwest Georgia Textile League through college teammates with ties to the Floyd County area. A summer job and the chance to play in a popular baseball league were good enough incentives to lure several college players, such as Harry Boss of Vanderbilt and James “Mac” McClanahan from Oglethorpe University, to Floyd County, and many of them returned to the area to settle when their college days were over. The use of college players worked well for both parties—the players had a chance to continue their training away from school, and the mill enjoyed access to fresh talent every baseball season. In turn, the textile league offered local players a chance to hone their athletic skills, which often led to college scholarships and a recurring spot on a college baseball team, as was the case of Willard Nixon, a Floyd County native who used his experience on a textile-league team to earn a scholarship to Auburn University. [EDITORS’ NOTE: See Wynn Montgomery’s article “Georgia’s 1948 Phenoms and the Bonus Rule” in the summer 2010 issue of The Baseball Research Journal.]

At the heart of every textile-league game were the players themselves. The fiercely competitive league fostered talented players and entertained northwest Georgia with a brand of baseball still remembered today. Most players came from the local area and ranged in age from eighteen to thirty-six, although mills would recruit college players to work and play for the company each summer. “College boys” were usually recruited from Southern schools such as Vanderbilt, Auburn, and Oglethorpe. Most of these players became aware of the Northwest Georgia Textile League through college teammates with ties to the Floyd County area. A summer job and the chance to play in a popular baseball league were good enough incentives to lure several college players, such as Harry Boss of Vanderbilt and James “Mac” McClanahan from Oglethorpe University, to Floyd County, and many of them returned to the area to settle when their college days were over. The use of college players worked well for both parties—the players had a chance to continue their training away from school, and the mill enjoyed access to fresh talent every baseball season. In turn, the textile league offered local players a chance to hone their athletic skills, which often led to college scholarships and a recurring spot on a college baseball team, as was the case of Willard Nixon, a Floyd County native who used his experience on a textile-league team to earn a scholarship to Auburn University. [EDITORS’ NOTE: See Wynn Montgomery’s article “Georgia’s 1948 Phenoms and the Bonus Rule” in the summer 2010 issue of The Baseball Research Journal.]

At times, popular players would switch teams in the league in order to make additional money. A winning team was so important that mills would try to out-pay each other for the top players. For example, six supervisors at Brighton Mill in Shannon once pledged a dollar from their salaries each week in an attempt to lure the future major-leaguer Rudy York away from the Atco Mill in Cartersville, Georgia, to play for the Brighton Mill team.[fn]Harry Boss interview, 14 February 2003; James C. McClanahan interview, 14 February 2003. Harry Boss and “Mac” McClanahan were not originally from Floyd County. Mr. Boss’s family moved to Floyd County when his father was transferred to Tubize Mill. Boss played baseball at both Vanderbilt University and for Tubize Mill, eventually returning to Floyd County after college, where he still resides today. “Mac” McClanahan had no ties to the Floyd County area prior to his college years. While on a baseball scholarship at Oglethorpe University, McClanahan was asked to play on the Tubize Mill team for a summer. McClanahan played for the Tubize team for a few seasons, but was so impressed by the people of the area that he moved to Floyd County after his college career and baseball career ended. Also, see McCain, PastTimes, 46–47.[/fn] Having a winning baseball team in such a closely knit and competitive area proved that a particular mill community stood out above the rest and helped raise all those associated with that community above their typical social status. The players represented all of the workers in the mills, helping them overcome the pejorative label of “lint-head.”[fn]Jackie P. Shores interview, 29 October 2000; Beth Gibbons interview, 19 September 2000; McCain, PastTimes, 46–47; Sonnenburg, “When Textile Mill Athletes Were Champs,” 8.[/fn]

Players were popular both on and off the field. These “hometown heroes” lived and worked with their fans, inspiring countless local children to be the new generation of baseball players. “These great players were the people we saw every day,” one community member remembers fondly. “Star” players enjoyed upward social mobility within the community and also helped to raise the status of the community as a whole. Some players from the Floyd County area went beyond the textile league to have careers in both the minor and major leagues, elevating them to a new level of local fame. Yet the status of local hero was enough for at least one player; “Lefty” Sproull turned down a spot on a professional baseball team to remain a mill worker and player for the Goodyear plant in Rockmart, Georgia. Others (including Rudy York, Leon Culberson, Willard Nixon, and Joe Tipton) used their textile-league prowess to follow their dreams to the big leagues.

For some citizens in the Floyd County area, textile league baseball provided not only a source of community pride but also a way to survive. Especially during the Depression, a number of unemployed Georgians used their baseball talents to try to win a spot on a mill baseball team and thereby secure a job in the mill itself. As one former player recalls, “If you could play, you got a job.” Reflecting on that time, the same player added, “Today players get paid millions of dollars. Back then, we were just lucky to have a job.”[fn]Harry Boss interview, 1995.[/fn]

Even with all of the opportunities it afforded to both the players and the community, the Northwest Georgia Textile League was not impervious to the economic turmoil of the Depression. The General Textile Strike of 1934 reached the South in early September with 200,000 mill workers eventually participating in it. Although Floyd County was never at the center of activity during the revolt, the “Strike of ’34” did cause snags in the fabric of mill life and mill baseball in that area of northwest Georgia.[fn]Michelle Brattain, The Politics of Whiteness: Race, Workers, and Culture in the Modern South (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 53.[/fn]

Floyd County textile mills and their baseball teams were unaccustomed to the nuances of organized labor when the General Textile Strike began. Labor unions had never been a strong force in the community. The two earlier strikes that had affected the textile mills in Floyd County had been brief and disorganized. The first strike had taken place at the Lindale Mill in 1896, when white workers had protested management’s decision to let a black worker fill in as a machinery operator. The other strike had occurred in 1933, when several workers at Anchor Duck Mill organized a walkout in protest of increased workloads and a decrease in shift hours.[fn]Ibid., 37–38, 64–65.[/fn]

The widespread organization of the textile strike in 1934 caused a ripple effect in Floyd County mill life. The workers, according to the historian Michelle Brattain, were generally confused and disorganized by the strike—if they bothered to participate in it at all. Both Brighton Mill and Anchor Duck Mill employed significant numbers of workers who supported the strike. However, Brattain maintains that only 40 percent of the total textile workforce in Floyd County participated in strike activities, and most of those workers became involved only after the strike had already begun. For those Floyd County mills that had striking workers, production halted briefly, if at all. Most workers were indifferent to the strike. Floyd County experienced no real conflict as a result of the strike, and the only violence stemmed from a clash between a mill guard and a drunken deputy at Lindale Mill. Even when that story appeared in the local newspaper, millhands in Floyd County still reported to work.[fn]Ibid., 53, 68–71, 78–84.[/fn]

The General Textile Strike of 1934 did affect the Northwest Georgia Textile League in two major ways. When managers at Lindale Mill feared that a “flying squadron” of union organizers might arrive at the mill, they deputized the baseball players as mill guards. The squadron never appeared, suggesting that the players were respected enough by the community that their presence alone could dissuade union violence during the strike. When the strike began, league officials decided to cut the 1934 season short and to cancel the annual championship series, declaring Shannon and Lindale co-champions. By the following spring, play resumed for the Northwest Georgia Textile League, and it again was baseball as usual in Floyd County.[fn]Ibid., 68–69.[/fn]

Throughout the Great Depression, Northwest Georgia Textile League baseball proved to be the most popular form of organized recreation in the Floyd County area. In an era when helplessness and poverty were everyday occurrences, the game provided a medium through which textile-league players and the community of workers they represented could survive the rough economic conditions of the time and maintain a sense of social pride. However, by the beginning of the 1940s, world events were set in motion that would forever change the face of mill life and textile league baseball in Floyd County and elsewhere.

As America entered World War II, focus shifted from the economic troubles at home to the fighting in Europe and the Pacific. With many players trading baseball uniforms for military gear, professional baseball in the United States faced a precarious situation. In Floyd County, the stresses of the war took their toll on mill baseball. In 1941, league officials shortened the NWGTL season by six weeks, creating a 24-game schedule for each of the seven teams, to accommodate the Goodyear mills’ increased production requirements.[fn]Rome News Tribune, 12 March 1941.[/fn] As the war intensified, the league rosters lost more and more players as the citizens of Floyd County answered the call to arms. In March 1942, the NWGTL announced that it would not operate that year “due to local as well as general wartime conditions.” At the same time, the Rome News Tribune announced the creation of a new league, the Floyd County Textile League, which would “provide the local fans some enjoyment of their favorite local pastime”[fn]Ibid., 29 March 1942.[/fn] and would play with “retreaded” baseballs—used balls with new covers.[fn]Ibid., 12 April 1942.[/fn] This new league had only four teams, all of which had been members of the NWGTL: Tubize, Lindale, Anchor Duck, and the Orphans.[fn]C. J. Wyatt, personal communication with the author, 28 February 2003.[/fn]

The Orphans were a team unique to the time. Composed mostly of players from Brighton Mill or any of the three Goodyear mills who were either too old or too young for military service, the Orphans were the creation of Rome businessman and league statistician C. J. Wyatt. A baseball fan, Wyatt provided uniforms and equipment to the “orphaned” players, allowing them to split whatever profits they earned from playing baseball games. According to C. J. Wyatt’s son, the Orphans were the only team in the history of the area’s textile leagues for which players who did not work in the mill were allowed to compete.

At the end of the abbreviated season, the Anchor Duck team collected its first championship trophy— and the only Floyd County Textile League trophy ever, as the league did not return in 1943. Some of the larger mills (notably Pepperell, Tubize, and Brighton) continued to support teams made up of veteran players too old for military service and high-school athletes, allowing teenagers like Willard Nixon, who later pitched for the Boston Red Sox, to get an earlier-thanusual start by filling the ranks of the textile teams.[fn]Wyatt, 28 February 2003; McCain, PastTimes, 46–47.[/fn] These “independent” teams gave local fans some baseball, but no organized league existed in the area until the war ended.

At the end of the abbreviated season, the Anchor Duck team collected its first championship trophy— and the only Floyd County Textile League trophy ever, as the league did not return in 1943. Some of the larger mills (notably Pepperell, Tubize, and Brighton) continued to support teams made up of veteran players too old for military service and high-school athletes, allowing teenagers like Willard Nixon, who later pitched for the Boston Red Sox, to get an earlier-thanusual start by filling the ranks of the textile teams.[fn]Wyatt, 28 February 2003; McCain, PastTimes, 46–47.[/fn] These “independent” teams gave local fans some baseball, but no organized league existed in the area until the war ended.

On the front lines of the war, ball players from the Northwest Georgia Textile League acted as ambassadors of the sport. One example is Jack Gaston, a textile player turned enlisted man who helped organize baseball games while stationed in England. Another Rome native, Nath McClinic, played on an African American military team that won the “Island Championship” in Iwo Jima.[fn]Max Gaston, letter to Heather Fincher, Rome News Tribune archives, Rome, Ga., 2003; Nathaniel McClinic, Personal communication with Doug Hamil, 4 March 2003.[/fn]

While local textile mills proudly supported players and workers serving their country, the U.S. government’s demand for increased production breathed new life into the industry and called for an increased focus on matters at home. Floyd County mills competed for the coveted Army-Navy “E” Award for production records. Mill baseball parks became venues for commemorating the community war effort in addition to hosting games. Parades of local military groups, ceremonies surrounding the Army-Navy “E” Award, and patriotic celebrations were held on mill baseball fields for the duration of the war.[fn]Gammon, p. LXVII, LIII.[/fn]

With the end of the war, baseball in Floyd County shifted roles once again. As players came home from active duty and returned to the mills, interest in the Northwest Georgia Textile League revived. By 1946, the league had regrouped, with five of the seven 1941 teams back in the fold. The Rome News Tribune predicted that it would “be rated as one of the strongest and oldest ‘loops’ in Georgia.”[fn]Rome News Tribune, April 14, 1946.[/fn] The teams played 32 of the scheduled 40 games, with weather canceling the others, and Pepperell (Lindale) won the first of two consecutive league championships.

Despite a successful season, only Lindale, Shannon, and Tubize were willing to commit to the league for the 1947 season. The teams that withdrew cited “fulltime working conditions” and their inability to attract the players needed to field competitive teams.[fn]Ibid., March 7, 1947.[/fn] League officials considered postponing the start of the season but avoided that prospect by adding a mill team from Bremen, Georgia. The league entered the 1947 season with only four teams, the fewest ever, and by mid-June the newest of those teams had withdrawn. Summerville replaced Bremen, and the league was able to finish its season.

The NWGTL was back to six teams for the 1948 season, but four of the teams were new. Lindale and Shannon were back, but the other stalwart league member, Tubize, was now part of a new league in the northwest Georgia area. The West Georgia Textile League also fielded six teams, including three other teams (Aragon and the Goodyear teams from Cartersville and Rockmart) that had been members of the NWGTL at some point in the past. Thus, northwestern Georgia was now asked to support two organized leagues totaling twelve teams.

The instability of the various leagues and the mobility of the teams continued in 1949. The Northwest Georgia Textile League again had six teams, but only three (Lindale, Shannon, and Trion) were returnees from the previous year. The other three transferred back from the West Georgia Textile League. Once again, however, the NWGTL did not offer the only games around. Rome, the geographic and population center of northwest Georgia, fielded a team (the Red Sox) in the North Georgia City League, which sported teams in four other nearby towns—Calhoun, Chickamauga, Dalton, and Summerville. Rome left this league in June to play “independent, semi-pro ball.”[fn]Ibid., 8 June 1949.[/fn]

| TEAM | YRS | ’31 | ’32 | ’33 | ’34 | ’35 | ’36 | ’37 | ’38 | ’39 | ’40 | ’41 | ’46 | ’47 | ’48 | ’49 | ’50 | ’51 | ’52 | ’53 | ’54 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anchor Duck[fn value=”44″]Located in Rome; Anchor Duck later called Anchor Rome[/fn] | 8 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | C | ||||||||||||

| Aragon | 6 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Bremen | 1/2 | X[fn value=”45″]Summerville replaced Bremen on 18 June 1947[/fn] | |||||||||||||||||||

| Calhoun | 1 | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Cartersville[fn value=”46″]Goodyear Mills; Cartersville [Bartow County] Mill, called Atco[/fn] | 14 | X | C | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Cedartown[fn value=”46″][/fn] | 13 | C | X | C | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Chattooga Co. | 2 | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dalton | 1 | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lindale[fn value=”47″]Pepperell Mills[/fn] | 20 | X | X | X | C2 | X | X | X | X | X | C | X | C | C | X | C | X | X | X | X | X |

| Rockmart[fn value=”46″][/fn] | 12 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Shannon[fn value=”48″]Brighton Mills[/fn] | 19 | X | X | C1 | C | C | C | X | X | X | X | X | X | C | X | C | C | C | C | X | |

| Summerville | 1/2 | X[fn value=”45″][/fn] | |||||||||||||||||||

| Tallapoosa | 4 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Trion | 4 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Tubize[fn value=”49″]Tubize-Chatillon (Celanese) Mill located in Rome[/fn] | 13 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | C | C | X | C | X | X | |||||||

| TOTAL TEAMS | 20 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

- C=League champion

- C1=Champion, first half

- C2=Champion, second half

During the eleven years that the league existed before disbanding during World War II, five teams were part of the league every year, and another joined in the second year and remained for the next ten years. Only two other teams participated before the war, and they played for three and four consecutive years, respectively. Following the war, only two teams were in the league for all nine years, while thirteen other teams came and went, with only two being league members for as many as four years. Two others lasted less than a full season. These fluctuations in league membership reflect the changing times and the many reasons that the Northwest Georgia Textile League was never able to recapture the popularity it had held for local citizens prior to the war. According to the announcer Lee Mowry, factors such as the growth of community youth baseball and the loss of friends and family to the war kept the league from reclaiming its special role in the area.[fn]Broadside (Rome, Ga.), 17 February 1977; Rome News Tribune, 20 February 1947, 23 February 1947, 30 June 1947, 2 July 1947, 6 September 1947, 4 April 1951, 23 April 1951, 26 April 1951, 4 June 1952, 22 November 1953, 4 June 1954.[/fn]

A change in perception by returning players also fed the decline of the Northwest Georgia Textile League in the Floyd County area. Their war experiences had changed their perspective of the game. Former player Billy Primm explained his mindset after the war: “After what I had seen overseas, baseball just didn’t seem that important anymore.”[fn]William Primm interview, 14 February 2003; personal recollections of Heather Bostwick. The author lived in Floyd County for twenty-eight years, attended Pepperell High School in the Lindale community between August 1989 and May 1993, and witnessed a shift in focus from highschool baseball to high-school football in the area.[/fn]

Another factor to consider in the decline of the Northwest Georgia Textile League is the shifting role of the mills themselves by the late 1940s. The boom in demand for textile goods during the war decreased sharply when the conflict ended, creating a slump for some textile mills, many of which changed ownership in the years following the war. In turn, the economic losses for textile mills decreased their dominance of the economy in many areas of Georgia, including Floyd County.

The mill workers in Floyd County were also changing in post–World War II Georgia. Workers could now find better pay and improved working conditions in places other than a mill village. In addition, the GI Bill allowed workers who could not afford an education before the war to go beyond the mill village and find other occupations. These circumstances served not only to end the Northwest Georgia Textile League but spelled the beginning of the end for traditional millvillage life in Floyd County.[fn]Brattain, The Politics of Whiteness, 165.[/fn]

As the strength of the textile league continued to wane, professional baseball returned to northwest Georgia. The city of Rome entered a team, the Red Sox, in the Class D Georgia-Alabama League in 1950. That team, which included some veterans of textile ball, lasted only two years; the textile league itself continued to operate through 1954, fielding four teams some years and six teams in others. The Pepperell (Lindale) and Brighton (Shannon) Mills were the only constants, and league membership was never the same from one year to the next.

Even after the league was no more, the last few mill-sponsored baseball teams in the area played their games against other community teams. With the arrival of the former Milwaukee Braves in Atlanta in 1966, the major leagues no longer just visited northern Georgia. Now they had a permanent home in the hearts and minds of fans with a new “home team” to rally behind. On a local level, the Floyd County community’s focus shifted from mill teams to high-school baseball, which enjoyed several years of popularity before eventually being replaced as the top sport by high-school football. Although many of the mills in the Floyd County area continued production well past World War II, beginning in the 1950s and 1960s, mill villages became less cohesive as worker houses and businesses were sold off to individuals. By the turn of the twenty-first century, the mills had become only parts of larger communities rather than the communities themselves. As of 2009, the former Brighton Mill at Shannon, Georgia, is the only one of the original buildings that remains in use as a textile company, now Gayley & Lord.[fn]Floyd County Heritage Book Committee, 134; Rome News Tribune, 22 November 1953, 26 February 1982; Senior Times (Rome, Ga.), October 1989.[/fn]

The Northwest Georgia Textile League lives on in the collective memory of the community. The Floyd County area houses a network of folklore and folklife traditions surrounding baseball, from the years of the Great Depression up to the present day. Floyd County now boasts its own Hall of Fame, founded in the late 1960s to showcase the achievements of local athletes, many of whom were textile-league players.[fn]Rome News Tribune, 22 January 1971, 4 March 1975, 2 March 1976, 21 September 1989, 23 February 1996), Baseball Reference, www.baseball-reference.com.[/fn]

Although no formal history of the Northwest Georgia Textile League has been written, oral traditions perpetuate the stories and legends of the teams and players throughout the Floyd County community. Often the players themselves relate their own stories to younger fans through reunions and community interaction, thus contributing and adding to their legendary status. Former player Harry Boss stated, “When we get together and start talking, we seem to become much better players than we really were back then.”[fn]Harry Boss, interview, 1995; Rome News Tribune, 13 March 1983.[/fn] The stories associated with the Northwest Georgia Textile League also help remind the community of its industrial ties, since many of the mills are no longer in business and the mill villages were divided into private lots long ago.

During the years that the Northwest Georgia Textile League was active, the customs surrounding the players, the teams, and their fans served to unite the members of the Floyd County community and bolster the community spirit of the industrial families within the area. The All-Star players, the game rivalries, the community social patterns, the mill owners, the fans—the many elements that created and supported this baseball league—each represents a different tradition in the historical collage of northwest Georgia. Their interaction created an outlet that allowed the people of that region to persevere during times of economic hardship, especially when faced with the Great Depression, when pay was low and chances of advancement were few.

Overall, the traditions and activities of the Northwest Georgia Textile Baseball League demonstrate a dynamic baseball tradition in the Floyd County area and paint a picture of a close-knit community that found that baseball played close to home gave a more personal face to the game, a face that was not unlike their own. Community itself was an important element from the tough times of the 1930s through World War II, giving mill workers in the area a medium for bonding with neighbors who shared similar backgrounds and experiences. For the Floyd County area, the traditions that surrounded local baseball during this time instilled a sense of community pride while elevating the importance of baseball to which members of the community still bear witness today.

The three decades of the Northwest Georgia Textile League represent the ultimate combination of business and baseball. For the mill owners and managers, baseball represented a “safe” leisure activity that tied workers to their jobs and communities and granted “bragging rights” to mill administrators who produced winning teams. For the players, the league served as an economic buffer against the hardships of the Depression, a method for securing an elevated place within their community, and a chance for a few to use their athleticism to propel them out of the mill village and into the big leagues. For the mill villagers as a whole, baseball provided a break from the monotony of the work week, a social outlet for the community, and a way to enjoy improved social status vicariously through winning teams and famous players.

This symbiotic relationship served to elevate mill baseball to an unprecedented height within the Floyd County area, resulting in almost thirty years of league activity that even the labor unrest of the Depression could only minimally affect. The bond forged between textile-league baseball and the Floyd County area was so strong that the memories of this brand of baseball still live on, decades after the last inning has ended and the last fan has left the stands. Player reunions, newspaper articles, and the stories handed down through the generations have helped preserve the memory and importance of mill baseball in the collective consciousness of the Floyd County community.

HEATHER S. SHORES is assistant director of the Bandy Heritage Center for Northwest Georgia at Dalton State College. Her research on baseball in Northwest Georgia is on display in the exhibition “Homefield Advantage: Memories of Professional Baseball in Northwest Georgia” at State Mutual Stadium in Rome, Georgia.