Fernandomania

This article was written by Vic Wilson

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

Jaime Jarrin, the Dodgers Hall of Fame Spanish-language broadcaster, tells the story that Walter O’Malley wanted to tap the growing Latino market in Southern California by finding a Mexican Sandy Koufax. O’Malley was not alive to see his dream realized when Fernando Valenzuela broke in with the Dodgers in late 1980.1 Valenzuela’s two wins, one save, and 17 2/3 scoreless innings gave a glimpse of what the future was to bring.

April 9, 1981 saw the birth of Fernandomania. Valenzuela, at the time the No. 3 starter, was moved up to pitch the opener due to an injury to Jerry Reuss. His five-hit shutout of the defending division champion Houston Astros caught everybody’s attention. What Fernando did in his first 8 starts was a streak for the ages: 8 wins, 7 complete games, 5 shutouts and 4 earned runs surrendered in his first 72 innings. In streaks of over 80 innings, only Bob Gibson’s 3 earned runs in 103 innings In 1968 was better than Fernando’s 4 earned runs in 89 2/3 innings dating back to 1980.2

He was to become the biggest story in baseball on the field in the first half of the 1980s.

In the 1981 strike-shortened season, Fernando became the first player ever to win the Rookie of the Year and Cy Young awards in the same season. Valenzuela beat out Tom Seaver in a close race (70 to 67 votes). Numbers that undoubtedly swayed the judges included more innings (192 to 166), shutouts (8 to 1), complete games (11 to 6), strikeouts (180 to 87), and a slightly better earned run average than Seaver (2.48 to 2.54). He also won the Silver Slugger award as the best hitter at his position.

Fernando’s reputation was enhanced with wins in both the 1981 division and league championship series. His Game Three win in the World Series—a gut-wrenching 147-pitch, 5–4 victory—was the turning point as the Dodgers began a four-game win streak to beat the Yankees.

Upon receipt of the Cy Young Award in November 1981, Fernando was asked by the press if he knew who Cy Young was. His answer: “I do not know who he was, but a trophy carries his name so he must be someone very special to baseball.”3

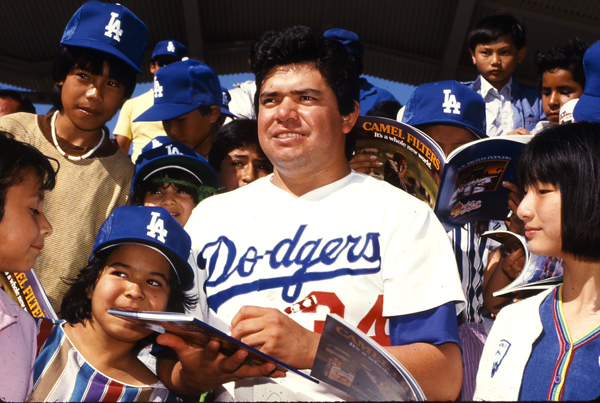

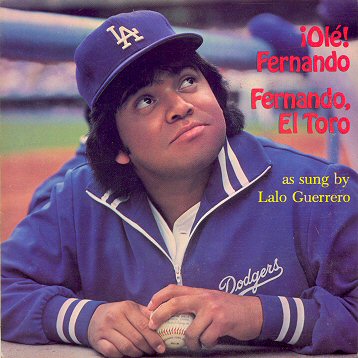

Fernando’s journey from the barren, dry lands of northern Mexico to the heights of baseball royalty made him the toast of two countries. Meeting with presidents, dealing with the press and a multitude of fans, Fernando always kept his bearings, saying, “I knew I was representing Mexico to many people.”4 Fernando had become a cultural icon, much larger than his performance on the field.

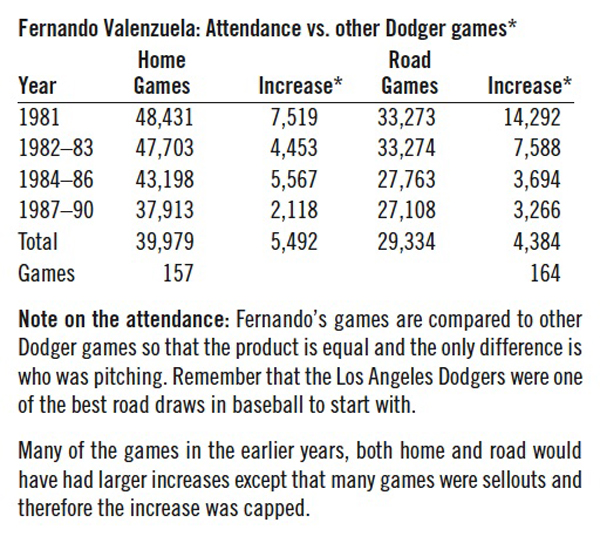

Fans flocked to Dodgers games at home and on the road. Eleven of Fernando’s 12 starts at Dodger Stadium in 1981 were sellouts. On the road during his first two years, Valenzuela’s starts drew more than 13,000 more people than other Dodger starters. Prior to 1981, the Dodgers had only broken the 3 million mark in attendance twice. From 1982 to 1986, home attendance was over 3 million every season. The Dodgers broke the major league attendance record in 1982 with 3.6 million fans and slipped only slightly to 3.5 million in 1983.

While many excellent pitchers over history had brought extra people to the ball park, Fernandomania was different. What Fernando did that was unique is best summed up by Jaime Jarrin: “I truly believe that there is no other player in major league history who created more new fans than Fernando Valenzuela. Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Joe DiMaggio, even Babe Ruth did not. Fernando turned so many people from Mexico, Central America, South America into fans. He created interest in baseball among people who did not care about baseball.”5

Latinos from California to halfway to Antarctica had found a new hero. Fernando’s games were broadcast on television in Mexico City, a city twice the size of Los Angeles and bigger than New York City. The number of radio stations broadcasting Dodgers games in Mexico jumped from 3 to 17. At the height of Fernandomania, the Spanish broadcasts had more than twice the listening audience of Vin Scully.

The Dodgers had been the first major league team to broadcast in Spanish but Latino attendance remained relatively low — 8 percent of the total in a region where the Spanish-speaking population was growing. Fernandomania brought that percentage up to close to 30 percent in the mid-eighties. More importantly, Fernando had changed the “face of Dodger Stadium” attendance. In 2005, Jaime Jarrin said 42 percent of Dodgers’ attendance was Latinos.6 The legacy of Fernandomania still lives.

Fernando became the most important Mexican player in major league baseball history. Only Bobby Avila, with an American League batting championship in 1954, was of any previous note. Before Fernando, most of the Latino stars had come from the Caribbean, such as Roberto Clemente of Puerto Rico and Juan Marichal of the Dominican Republic.

Fernando Valenzuela went on to pitch 11 years for the Dodgers (1980–1990). He won 141 games (8th in franchise history). He was also a six-time All Star (1981–1986) and third in the Cy Young voting in 1982 with 19 wins and second in 1986 when he led the league in wins with 21. In five appearances in All-Star Games (7 2/3 innings), Fernando did not give up a run. In the 1986 All-Star Game, he struck out 5 batters in a row to tie the record of another screwballer, Carl Hubbell, who did it in the 1934 All-Star Game. His overall postseason record was 5–1 with a 1.98 earned run average. From 1981 to 1987 Fernando won more games than any other National League starter and had the second-best ERA of NL pitchers with 1,000 innings during that period (second to Nolan Ryan). Fernando actually struck out more batters than Ryan during those years, 1448 to 1438. Fernando had six consecutive seasons of over 250 innings and it could have been seven without the strike in 1981. Given current trends in pitcher usage, it’s likely Valenzuela will be the last pitcher who had six consecutive seasons of 250 innings and a season of 20 complete games.

By 1988, however, all those innings had taken their toll, and Fernando missed part of the season due to a dead arm. He would never be as effective again. Valenzuela pitched two more seasons for the Dodgers with his final highlight being a no-hitter in June 1990.

After all the millions of dollars Fernando had made the Dodgers either directly or indirectly, he was let go in a cost-cutting move. Being cut was bad enough, but. the timing was worse. Since it happened late in spring training when most rosters were set, he found it difficult to find a new team. He appeared in two games for the Angels that year. Even though he went on to pitch until 1997, Fernando was angry at the Dodgers for more than a decade, refusing to attend Dodgers games as a spectator, despite living ten minutes from the ballpark, or to participate in Dodger-sponsored events.

But in 2003 the prodigal returned. Valenzuela accepted a color analyst position with the Dodgers Spanish Network, sharing the booth with Jaime Jarrin and Pepe Yniguez. In 2003 Valenzuela was inducted into the Hispanic Heritage Baseball Hall of Fame and in 2005 he was named one of the three starting pitchers on the Major League Baseball’s Latino Legends Team. In addition, Fernando became a coach for Mexico in the World Baseball Classic in 2006 and 2009.

Only the words of Vin Scully can put Fernando Valenzuela and Fernandomania in proper perspective. “But in baseball, Fernando…was a religious experience. You’d see parents, obviously poor, with the little youngsters by the hand, using him as inspiration.”7

VICTOR WILSON, a SABR member since 1984, has been a baseball and Braves fan ever since his fourth grade teacher, Miss Braun (a nun from Milwaukee) “beat it into him” in 1955. His major interests have been adjustment of player statistics (cross era and ballpark adjusted) with major associates being Pete Palmer, Michael Schell, and Ron Selter. His all time favorite players over the years have been Eddie Mathews, Sandy Koufax, Hank Aaron, Fernando Valenzuela, Greg Maddux, and now Tim Lincecum.

Notes

1 Jorge Martin, “25 Years After Fernandomania,” Dodger Magazine, 18 August 2006.

2 Orel Hershiser gave up 4 earned runs in 82 innings and Don Drysdale gave up 4 earned runs in 81 innings.

3 Mark Heisler, “He Came, He Pitched, He Conquered” Sporting News 1982 Baseball Yearbook, 5.

4 Jim Murray, “Fernando Throws Age a Screwball,” The Great Ones, Los Angeles: Los Angeles Times Books, 1999, 74.

5 Martin, op. cit.

6 Martin, op. cit.

7 Curt Smith, Pull Up a Chair, the Vin Scully Story, Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2009. 185.