The Bucs in San Berdoo

This article was written by Fred R. Peltz

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

Although the arrival of Major League Baseball in Southern California is usually dated to 1958, when the Brooklyn Dodgers moved to Los Angeles, big league clubs had roots in the area going back several decades. The Chicago Cubs began training in L.A. in the spring of 1903, and the White Sox played an exhibition game in Riverside in 1914. From 1924 to 1934, the Pittsburgh Pirates trained in the central California town of Paso Robles. The club then got a pitch from a San Bernardino civic group led by Harrison Sporting Goods, the regional supplier of Spalding Sporting Goods, the chief provider of equipment to the big leagues.

As longtime resident Bill Harrison told the San Bernardino Sun in 1999, his parents, William and Laura Harrison, owned Harrison Sporting Goods and put the request to the Spalding Company, which relayed it to the Pirates. The invitation had merit for several reasons. San Bernardino, a citrus-growing center of a region known as the Inland Empire, enjoyed a benign climate. Located 50 miles east of L.A. and the Pacific Ocean, the city had grown in prominence as the gateway to Southern California, given its intersecting highways—including the marvelous Route 66—and railroads. The city’s transportation hub made it convenient to play the other big-league clubs who trained at that time in Southern California: the Chicago White Sox in Pasadena, and the Chicago Cubs on Catalina Island. The St. Louis Browns trained in San Bernardino in 1948, then several years in Burbank (1949–52), and returned to San Bernardino in 1953. The Philadelphia Athletics trained in Anaheim in 1940–42 and the Cleveland Indians in Tucson, Arizona, 1947–1992, adding to the competition, as did the New York Giants, who trained in Phoenix 1947–50 and 1952. The Triple-A teams of the Pacific Coast League provided further opportunities for games.

As longtime resident Bill Harrison told the San Bernardino Sun in 1999, his parents, William and Laura Harrison, owned Harrison Sporting Goods and put the request to the Spalding Company, which relayed it to the Pirates. The invitation had merit for several reasons. San Bernardino, a citrus-growing center of a region known as the Inland Empire, enjoyed a benign climate. Located 50 miles east of L.A. and the Pacific Ocean, the city had grown in prominence as the gateway to Southern California, given its intersecting highways—including the marvelous Route 66—and railroads. The city’s transportation hub made it convenient to play the other big-league clubs who trained at that time in Southern California: the Chicago White Sox in Pasadena, and the Chicago Cubs on Catalina Island. The St. Louis Browns trained in San Bernardino in 1948, then several years in Burbank (1949–52), and returned to San Bernardino in 1953. The Philadelphia Athletics trained in Anaheim in 1940–42 and the Cleveland Indians in Tucson, Arizona, 1947–1992, adding to the competition, as did the New York Giants, who trained in Phoenix 1947–50 and 1952. The Triple-A teams of the Pacific Coast League provided further opportunities for games.

The Pirates agreed to make San Bernardino’s Perris Hill Park their spring training home in 1935, playing there off and on until the end of the 1952 exhibition season. San Berdoo, as it is popularly known, was an attractive spring training site for other reasons. The city had a population of about 40,000 in 1935 and sits at the base of the towering San Bernardino Mountains, where for a few years the Pirates stayed at the Arrowhead Springs Hotel, five miles from the city below. With its 36 springs, the hotel was a well-known spa frequented by Hollywood celebrities. The hotel was devastated by a forest fire in 1938 but was soon rebuilt. When it re-opened in December 1939 entertainers Judy Garland, Al Jolson, and Rudy Vallee were there to celebrate the occasion. Each spring the Pirates rubbed shoulders with radio and film celebrities.

A few years later the club moved its headquarters downtown to the California Hotel, another favorite stop for Hollywood stars and other notables, as it was located across the street from the West Coast Theater, which hosted several movie premieres. Charlie Chaplin, Bette Davis, and John Wayne were among those who signed the hotel’s guestbook. Some Pirates dabbled in the Hollywood scene, such as Pirates manager Frankie Frisch, who used an off-day in 1941 to make the short drive to Palm Springs to appear on Jack Benny’s radio show.

In those years, clubs tended to shift spring training sites often, and Pittsburgh was no exception. After initially training in San Bernardino in 1935, the Pirates spent the next spring in San Antonio, Texas, before returning to San Bernardino through 1942. Pittsburgh then trained in Muncie, Indiana, during the rest of World War II (1943-45), spent 1946 back in San Bernardino, then trained in Miami, Florida in 1947, and in Hollywood in 1948. The Pirates’ springtime returns to town were always cause for civic celebration. The arrival time of the team’s train at the Santa Fe railroad depot downtown was announced in the San Bernardino Sun, players were greeted with music by the San Bernardino High School band, and the city’s mayor and the queen of San Bernardino County’s National Orange Show joined the reception committee.

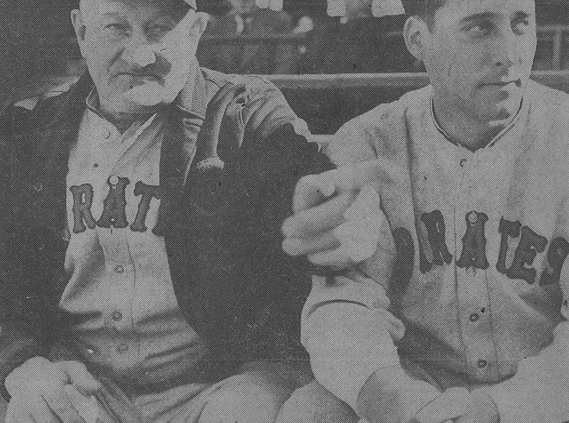

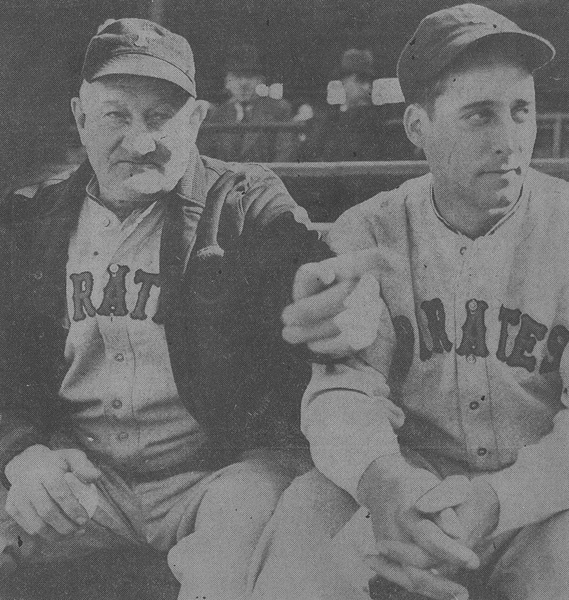

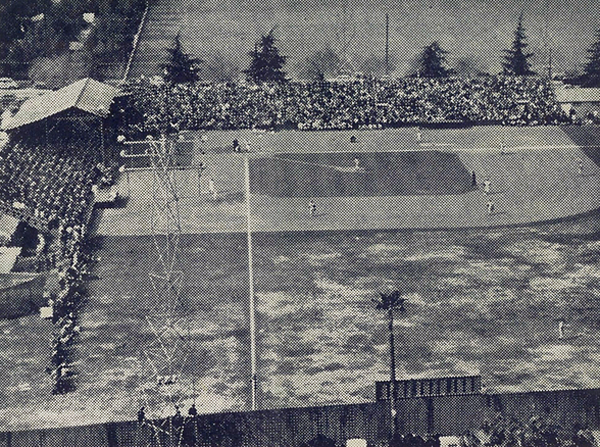

For most Inland Empire residents, Perris Hill Park provided their only means of seeing a major-league ballplayer up close. The expansion of big-league teams west of the Mississippi River was still decades away, as were televised games, and local baseball fans’ visual impressions of their favorite players were limited to snippets on movie newsreels, magazine photos, newspaper reproductions, and images on Wheaties boxes. The Pirates may have often experienced lean seasons after training in San Bernardino—Pittsburgh’s best finish in those years was second in 1938 and 1944—but local fans were treated to an array of stellar ballplayers and managers when the Pirates were in town. At Perris Hill, fans not only could watch big-league players in person, they could see several who were among the best in the game’s history. The 1935 Bucs, for instance, were led by Honus Wagner (by then a coach and mentor), manager Pie Traynor, Arky Vaughan, and the Waner brothers, Paul and Lloyd, known as “Big and Little Poison.” The Pirates also had Truett “Rip” Sewell, the right-hander known for his looping “eephus” pitch. Harry “Cookie” Lavagetto played for Pittsburgh 1934–36 before moving to the Brooklyn Dodgers. And Albert “Al” Gionfriddo—forever remembered for robbing the Yankees’ Joe DiMaggio of a double in the 1947 World Series when Gionfriddo was playing his last major-league game as a member of the Dodgers—spent most of his four seasons with the Pirates. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, fans always thrilled to see the Bucs’ left fielder Ralph Kiner, who won or shared the National League home-run title in all seven of his seasons with the club. Kiner frequently commuted to Perris Hill from Alhambra, where he had grown up.

For most Inland Empire residents, Perris Hill Park provided their only means of seeing a major-league ballplayer up close. The expansion of big-league teams west of the Mississippi River was still decades away, as were televised games, and local baseball fans’ visual impressions of their favorite players were limited to snippets on movie newsreels, magazine photos, newspaper reproductions, and images on Wheaties boxes. The Pirates may have often experienced lean seasons after training in San Bernardino—Pittsburgh’s best finish in those years was second in 1938 and 1944—but local fans were treated to an array of stellar ballplayers and managers when the Pirates were in town. At Perris Hill, fans not only could watch big-league players in person, they could see several who were among the best in the game’s history. The 1935 Bucs, for instance, were led by Honus Wagner (by then a coach and mentor), manager Pie Traynor, Arky Vaughan, and the Waner brothers, Paul and Lloyd, known as “Big and Little Poison.” The Pirates also had Truett “Rip” Sewell, the right-hander known for his looping “eephus” pitch. Harry “Cookie” Lavagetto played for Pittsburgh 1934–36 before moving to the Brooklyn Dodgers. And Albert “Al” Gionfriddo—forever remembered for robbing the Yankees’ Joe DiMaggio of a double in the 1947 World Series when Gionfriddo was playing his last major-league game as a member of the Dodgers—spent most of his four seasons with the Pirates. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, fans always thrilled to see the Bucs’ left fielder Ralph Kiner, who won or shared the National League home-run title in all seven of his seasons with the club. Kiner frequently commuted to Perris Hill from Alhambra, where he had grown up.

Through the years, local fans also got to see other stars come to Perris Hill to play against Pittsburgh, such as Gabby Hartnett and Billy Herman of the Chicago Cubs, Luke Appling and Jimmy Dykes of the Chicago White Sox, and Philadelphia Athletics owner-manager Connie Mack. Even the lowly Browns offered future star power with Los Angeles-born infielder Johnny Berardino, who later would become a TV soap-opera star on General Hospital.

Through it all the Pittsburgh players remained “fun-loving guys and [were] having a good time” during the spring, attorney Ron Skipper told the Sun, adding that “they signed balls and they didn’t swat you away.” Skipper, whose family lived a few blocks from the California Hotel, had an especially keen interest in the team because his uncle was Bob Elliott, the seven-time All-Star outfielder and third baseman. His career included playing for the Pirates from 1939 to 1946 and winning an NL Most Valuable Player award after he moved to the Boston Braves.

San Bernardino was still growing but retained its small-town flavor, and ballplayers could easily be spotted when they weren’t on the diamond. Jack Brown, who later became chairman of the Stater Brothers supermarket chain, recalled how he and his friends watched games at Perris Hill and then scouted other locations to see their heroes. “When we got done with the game, we’d come back to downtown San Bernardino on our bikes and park them at the California Hotel and wait for the team to come down and go to dinner,” Brown told the Riverside (CA) Press- Enterprise in 2005.

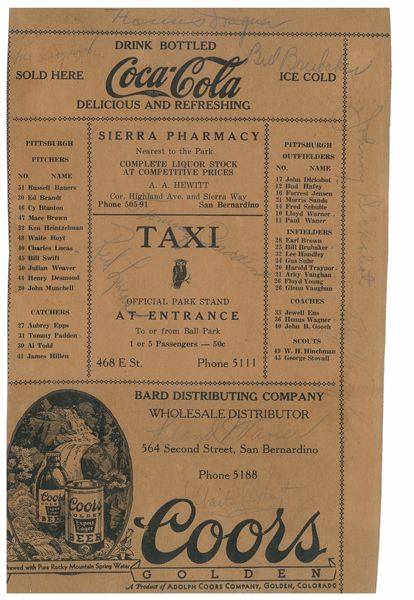

Built in 1927, Perris Hill was a diamond in the truest sense, with no rounding off of the center-field fence. It was 354 feet down the lines and 451 feet to dead center field. The ballpark later had a $10,000 overhaul that turned it into a facility that could host pro baseball. Perris Hill was one of the few parks that had lights for night play, courtesy of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration (WPA). Only a belt-high wooden fence down the third base line separated the players’ bench from the fans. A kid could easily walk up to Honus Wagner, tap him on the shoulder, and walk away with an autograph by the man many consider the best shortstop ever. Tickets ranged from 50 cents to $1.50, and one could even see big-league ball for as little as 25 cents when the Pirates played an intra-squad game at Perris Hill.

Built in 1927, Perris Hill was a diamond in the truest sense, with no rounding off of the center-field fence. It was 354 feet down the lines and 451 feet to dead center field. The ballpark later had a $10,000 overhaul that turned it into a facility that could host pro baseball. Perris Hill was one of the few parks that had lights for night play, courtesy of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration (WPA). Only a belt-high wooden fence down the third base line separated the players’ bench from the fans. A kid could easily walk up to Honus Wagner, tap him on the shoulder, and walk away with an autograph by the man many consider the best shortstop ever. Tickets ranged from 50 cents to $1.50, and one could even see big-league ball for as little as 25 cents when the Pirates played an intra-squad game at Perris Hill.

For some local residents, Perris Hill offered employment. George Beck, who read meters for the local gas company, supplemented his income by serving as the public address announcer at Perris Hill and other venues. For $15 a day, Beck would announce the line-ups from each manager and read advertisements to the crowd “so that the Pirates could pay for the lights.”

There was one other star-crossed Pirate of note who briefly played at Perris Hill in 1950: 19-year-old Paul Pettit. After a remarkable high school career in Harbor City, California, where Pettit threw six no-hitters and struck out 27 batters in one 12-inning game—the most since Walter Johnson in 1905—movie producer Frederich Stephani signed the young pitcher to a 10-year personal services contract for $85,000. Stephani wanted to film the life story of an athlete but couldn’t afford an established star, so he bet on Pettit’s future. Three months later, Stephani—in effect acting as Pettit’s agent while retaining the movie rights to his life—sold Pettit’s contract to the Pirates for $100,000. The St. Louis Cardinals and other teams cried foul, but Commissioner Happy Chandler’s subsequent investigation found no wrongdoing.

Pettit had become the first $100,000 “bonus baby,” and he spent two weeks at Pirates rookie camp at Perris Hill in 1950. Then he was assigned to the Double-A New Orleans Pelicans where he worked hard to merit his bonus. But, “for all the money the Pirates spent, there was no pitching coach in New Orleans to monitor him,” John Klima wrote in his book Deal of the Century. “Pettit was not trained. He was simply handed the ball. It was baseball in the dark ages.” In the third week of the season, Pettit hurt his elbow and, while favoring the injury, his shoulder. He finished the season 2–7 and had only two short stays with the Pirates, in 1951 and 1953. He reinvented himself as a power-hitting position player in the Pacific Coast League and in Mexico, but was never given another shot in the major leagues.

The end of World War II brought new ownership for the Pirates, who were purchased in 1946 by a syndicate that included actor-singer Bing Crosby. Also coming on board that year was Ralph Kiner, who recalled how Crosby, his kids in tow, often showed up at Perris Hill for Pirates’ practice and to take part in pepper games. He said Crosby treated the players well. When the Pirates went to Los Angeles for a game, he would take the team to Chasen’s for dinner. But Crosby’s charity and Kiner’s slugging success on the field didn’t mean much at contract time. In late 1950, the Pirates hired Branch Rickey, famous for his years running the Brooklyn Dodgers, as their general manager. Kiner, coming off one of his best seasons, expected a raise, but Rickey responded, “We finished last with you, we can finish last without you.” Largely due to continued salary disputes, Kiner eventually was sent to the Cubs in June 1953 as part of a 10-player trade.

In an odd twist, given Southern California’s vaunted climate, it was weather that caused the Pirates to abandon San Bernardino for good after the spring of 1952. Branch Rickey praised the field, the hotel accommodations, and the city’s cooperation, but he had soured on the weather after the rains that year were among the worst in Southern California history, with numerous practices and games cancelled. Instead Rickey accepted an offer to move spring training to Havana, Cuba. The following year San Bernardino enjoyed one more big league spring with the Browns, whose 1953 roster included legendary pitcher Satchel Paige, but that marked the end.

Perris Hill Park has remained connected to sports. In 1983 the field was renamed John A. Fiscalini Field, after the San Bernardino high school standout and UC Berkeley All-American outfielder, who later played in the Pirates minor league system from 1948 to 1950. In 1987, the ballpark became home to a single-A team, the San Bernardino Spirit of the California League. The city spent more than $1 million on improvements to the park during that period, increasing the seating capacity to 3,500 by 1996. The Spirit’s roster in 1988 included Ken Griffey Jr., then an 18-year-old Seattle Mariners prospect. In 58 games with the club, he batted .338. Baseball America named him its single-A player of the year.

Actor Mark Harmon, the team’s largest shareholder at the time, also visited Fiscalini Field in 1988, bringing Hollywood with him. The final scenes of Harmon’s movie Stealing Home were filmed at the field, with Harmon wearing a Spirit uniform. After the 1992 season, the Spirit’s ownership changed, and the team moved to a new stadium, the Epicenter, in nearby Rancho Cucamonga.

The city of San Bernardino, in order to meet changing minor league standards and thus keep professional baseball, built a $16.5-million facility, now called Arrowhead Credit Union Park, which opened in 1996. It is currently the home of the Inland Empire 66ers, the Angels’ single-A affiliate in the California League. City Parks superintendent Ed Yelton maintained in 1997 that the old ballpark was “far from dead.” The manicured diamond that once hosted the likes of Honus Wagner, Paul Waner, and Ralph Kiner now is used for youth, high school, and college baseball games, soccer tournaments, and even church revivals. Said Yelton: “I envision Fiscalini Field being here another 50 years.”

FRED R. PELTZ enjoyed his first taste of major league baseball in the late 1930s, watching Pie Traynor’s Pittsburgh Pirates spring training in San Bernardino, California. In 1947 while playing Junior Leagueball, he earned a trip to the World Series in New York and witnessed Jackie Robinson in his debut year. Peltz had a limited career pitching in the Sunset and Pioneer Minor Leagues from 1948–51. In 1954 he played with Dave Bristol on Army’s XVI1 Corps Championship team in Japan. Before retiring from newspaper advertising in Riverside, California, Peltz learned of SABR from co-worker Andy McCue. He credits McCue with introducing him to the wealth of available resources and camaraderie of SABR. Peltz has been married to Sue for 57 years and currently lives in San Clemente, California. They have five children and six grandsons.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge Sue Payne, docent, Arda Haenszel California Room, Norman F. Feldheym Central Library, San Bernardino, California; Sue Peltz; James F. Peltz; Joan Gonzalez; William Swank; and Al Parnis for their assistance.

Sources

Books

- John Thorn, Pete Palmer, Michael Gershman, and David Pietrusza, Total Baseball, Fifth Edition, Viking Penguin, 1997.

Periodicals

- “Spring Memories,” Mark Muckenfuss, Riverside (CA) Press-Enterprise, March 29, 2005.

- “SB’s no stranger to Baseball,” Gregg Patton, San Bernardino County Sun, 21 March 1999.

- “Picture Stars Participate in Full Program,” San Bernardino Daily Sun, 17 December 1939.

- “S.B.’s team, announcer recalls,” Nick Leyva, San Bernardino Sun, 28 July 1984.

- “Fiscalini’s upkeep grounds for concern,” Danny Summers, San Bernardino Sun, 18 March 1997.

Internet

- Klimaink.com, John Klima Baseball Writing, Deal of the Century.

- Ed Burns

- Baseball Reference.com Encyclopedia of Players

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- http://hwof.com/star/television/johnberardino/2354

- Steve Treder, The Hardball Times, “The Branch Rickey Pirates,” 10 March 2009.

- http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/mariners/2012145723, 5 July 2010.

- Geoff Young, The Hardball Times, “Produce great men, the rest follow,” 9 June 2010.