Jeane Hoffman: California Girl Makes Good in Press Box

This article was written by Jean Ardell

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

The experiences of 17-year-old Jeane Hoffman as she worked out of the press box at Wrigley Field, home of the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League.

The experiences of 17-year-old Jeane Hoffman as she worked out of the press box at Wrigley Field, home of the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League.

The battle women have faced to gain access to Organized Baseball’s locker rooms is, by now, well documented. Throughout the 1970s, many ballplayers were shocked, shocked, when increasing numbers of female sportswriters breached the privacy of that sanctum, with some declaring it merely an excuse to ogle athletes in a state of undress. Less known—and less understandable—are the obstacles such women faced to gain access to the press box, where presumably their male colleagues were fully and decently clothed.

Indicative of the era was the experience of the Cleveland News’ award-winning investigative reporter Doris O’Donnell, whom an editor sent to cover the Cleveland Indians’ eastern road trip in May 1957. O’Donnell’s presence as a female sportswriter became the story, with much analysis of her figure, and she was excluded from the Yankee Stadium press box. (O’Donnell, incidentally, was a role model for a local teenager named Dorothy Jane Zander, known later to SABRen as Dorothy Seymour.)

Indicative of the era was the experience of the Cleveland News’ award-winning investigative reporter Doris O’Donnell, whom an editor sent to cover the Cleveland Indians’ eastern road trip in May 1957. O’Donnell’s presence as a female sportswriter became the story, with much analysis of her figure, and she was excluded from the Yankee Stadium press box. (O’Donnell, incidentally, was a role model for a local teenager named Dorothy Jane Zander, known later to SABRen as Dorothy Seymour.)

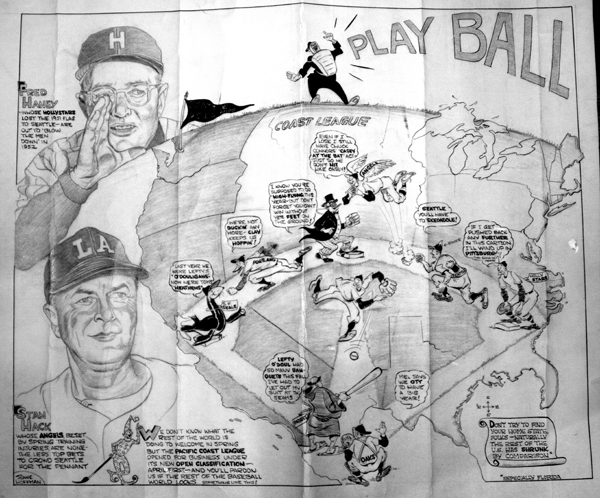

Twenty years before O’Donnell, however, 17-year-old Jeane Hoffman worked out of the press box at Wrigley Field, home of the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League.[fn]The spelling of Hoffman’s name appears in some by-lines and publications as “Hofmann.” [/fn] Despite her youth, Hoffman already had sportswriting experience. At Los Angeles High School she had studied journalism and cartooning, served as girls sports editor for the school’s semi-annual publication, and at age 15 was publishing sports cartoons in the Hollywood Citizen-News. Covering baseball, football, and hockey for that publication, she became the youngest regular writer in the history of the Pacific Coast League.

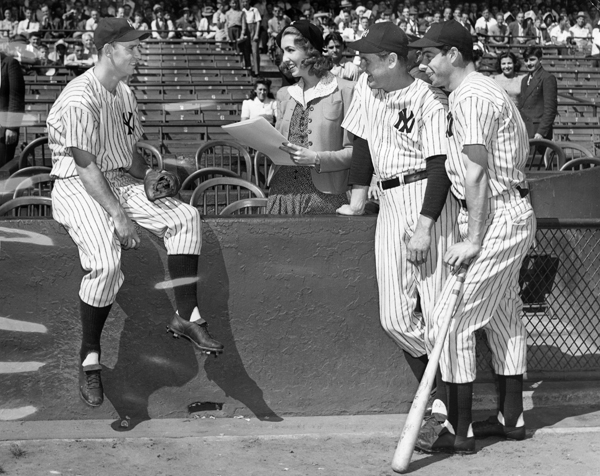

But Hoffman had her eye on major-league markets. In 1940, having learned of an opportunity at the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Hoffman and her mother, Ada, drove across the country at the rate of 600 miles a day. She got the job. As a writer-cartoonist, she was a regular in the Shibe Park press box, reporting games and drawing three-column sports cartoons. In 1942, Hoffman became the “first girl scribe” to cover spring training in Florida. She took advantage of her roving assignment to interview Bob Feller and Sam Chapman, then stationed at the Roanoke (Virginia) Naval Training Station, before continuing to Florida to cover the Cardinals, Tigers, Yankees, Reds, Phillies, Giants, and Red Sox.[fn]“Draws As She Writes,” 3 December 1942. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.) [/fn] By then, she had a job in the heart of the major-league baseball universe, New York City, with a by-line under her column “From the Feminine Viewpoint,” in the New York Journal-American.

“I don’t know how she managed to get that job,” said her friend Rosalind Massow, who worked at the newspaper as a copygirl. “The Journal-American was not notable for its women reporters. She must have been very convincing. I do know that the guys at the sports desk liked her—they were not competitive with her.”[fn]Rosalind Massow, telephone interview, 25 February 2011. [/fn] In an article that year entitled “No ‘End’ to Jokes, Girl Finds, in Yankee Stadium Press Box,” Hoffman took on the issue of access, writing with humor but nevertheless making her point:[fn]Jeane Hofmann, “No ‘End’ to Jokes, Girl Finds, in Yankee Stadium Press Box,” New York Journal-American, no date. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.) [/fn]

“I don’t know how she managed to get that job,” said her friend Rosalind Massow, who worked at the newspaper as a copygirl. “The Journal-American was not notable for its women reporters. She must have been very convincing. I do know that the guys at the sports desk liked her—they were not competitive with her.”[fn]Rosalind Massow, telephone interview, 25 February 2011. [/fn] In an article that year entitled “No ‘End’ to Jokes, Girl Finds, in Yankee Stadium Press Box,” Hoffman took on the issue of access, writing with humor but nevertheless making her point:[fn]Jeane Hofmann, “No ‘End’ to Jokes, Girl Finds, in Yankee Stadium Press Box,” New York Journal-American, no date. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.) [/fn]

We note that The Sporting News has been running a handy guide service on “How to Crash the Press Box,” alias “No Women or Dogs Allowed.”… We would like to add our two-bits’ worth (Confederate coin). But prepare yourself; this one’s gonna be different! To begin with, we haven’t a complaint in the world against the Gentlemen of the Press.…The boys have been darn nice to us. When we toured Florida last spring, we didn’t have more than 250 jokes played on us, and no more than 50 jesters tried to steer us into the players’ un-dressing room.

In an article syndicated in the Associated Press, she had accurately predicted a Cardinals-Yankees World Series; she closed out the season writing features on the World Series.

“Famous Woman Sports Writer Begins Series in Times Today” – Los Angeles Times, September 16, 1951

In January 1944, Hoffman became engaged to Thomas Allen McIntosh, a first officer in the British Merchant Marine, and they married in Portsmouth, Virginia, on February 15 of that year. Hoffman and her husband remained on the East Coast for several years before returning to Los Angeles in 1951, whereupon the Los Angeles Times hired her to write a weekly feature on sports. That November she gave birth to Joan Margaret, the first of three daughters. In September 1957, as Brooklyn Dodger fans faced the unthinkable, Hoffman published an 11-point analysis of the benefits attached to L.A. becoming a major-league city. The Times found it necessary to insert the following explanation at the beginning of the essay:[fn]Jeane Hoffman, “Big Boon”. [/fn]

(Jeane Hofmann, authoress of the following story, is qualified to discuss the importance of major league baseball to Los Angeles. She spent 12 years in Philadelphia and New York at major newspapers there, covering all sports, before she came to The Times. She knows the baseball picture there and here thoroughly.)

Hoffman laughed or shrugged off the patronizing comments and attitudes that attended her presence as a sportswriter. “Mom had a way about her…. She always seemed to have a very good knack for getting her story,” recalls her middle daughter, Valerie McIntosh, who thinks Jeane found support and encouragement from her own mother.[fn]Valerie McIntosh, telephone interview, 13 February 2011. [/fn] Valerie’s younger sister, Diane McIntosh, agrees. “Grandma had gotten a divorce and owned a number of rental properties. Our grandmother was very independent, so I can only imagine… that she fully supported her daughter. They were both women ahead of their time.”[fn]Diane McIntosh, e-mail to the author, 13 February 2011. [/fn]

Hoffman continued to cover the Dodgers’ move west, and their plans for a new stadium in Chavez Ravine. She profiled Vin Scully and the Dodgers’ front office executives, including Buzzie Bavasi. In May 1965 Dodgers’ owner Walter O’Malley circulated a memo to the front office: “Jeane Hoffman (McIntosh) has been retained by me ‘on special assignment.’ She will be furnished an office and will have Department Head courtesies. Calling cards will read ‘Assistant to the President.’”[fn]3 May 1965, Memo, Walter F. O’Malley to All Department Heads. (Courtesy Peter O’Malley.) [/fn] Her job entailed filling Dodger Stadium when the team was out of town and during the offseason, and she took on the assignment with enthusiasm, booking events from R.V. shows and bull fights to the National Football Foundation and Hall of Fame Scholar-Athlete Awards banquet in the Stadium Club and the filming of an Elvis Presley movie, Spinout.

Hoffman continued to cover the Dodgers’ move west, and their plans for a new stadium in Chavez Ravine. She profiled Vin Scully and the Dodgers’ front office executives, including Buzzie Bavasi. In May 1965 Dodgers’ owner Walter O’Malley circulated a memo to the front office: “Jeane Hoffman (McIntosh) has been retained by me ‘on special assignment.’ She will be furnished an office and will have Department Head courtesies. Calling cards will read ‘Assistant to the President.’”[fn]3 May 1965, Memo, Walter F. O’Malley to All Department Heads. (Courtesy Peter O’Malley.) [/fn] Her job entailed filling Dodger Stadium when the team was out of town and during the offseason, and she took on the assignment with enthusiasm, booking events from R.V. shows and bull fights to the National Football Foundation and Hall of Fame Scholar-Athlete Awards banquet in the Stadium Club and the filming of an Elvis Presley movie, Spinout.

In an undated letter sent to O’Malley during spring training 1966, Hoffman began, “Dear Walter, Well, how are all the heroes down in Vero?” and went on to alert him about the prospect of the Beatles performing at Dodger Stadium that August.[fn]Jeane Hoffman, letter to Walter O’Malley, undated, 1966. [/fn]

Her daughters often accompanied their mother to the ballpark. Valerie McIntosh, whose godmother was Eleanor Gehrig, recalls, “being bounced on the knees of Drysdale and Koufax…. We saw lots of games—we always sat up on the club level by the offices. Mom covered everything in L.A., from the Rams, to John Wooden’s UCLA basketball team, to Santa Anita Race Track, and lots of tennis. At the Christmas party she always held, all the sports people in town came.”[fn]McIntosh, telephone interview. [/fn]

By the mid-1960s the women’s liberation movement was gaining momentum; American women were beginning to act upon their professional dreams. Within a few years, increasing numbers of women began covering baseball, and the press box signs forbidding women access came down. But in 1966 Jeane Hoffman had already had it all—marriage, family, and a successful career in a man’s field—for two decades. Her success can be attributed to talent, a healthy sense of humor, the support of a strong mother, and, perhaps, starting out in sportswriting so young that she simply did not accept the status quo. In late spring of 1966 an award was established in her name: The Theta Sigma Phi-Jeane Hoffman Unique Coverage Award. Several months later, however, on September 29, 1966, she was at home recovering from a virus when she was stricken with a pulmonary embolism. She died at age 47, leaving her husband and three daughters aged 15, 13, and 11. As that year’s World Series got under way, her former colleague at the Times, Sid Ziff, recalled her career:[fn]Sid Ziff, “Series Fever,” Los Angeles Times, 4 October 1966. [/fn]

Jeane could have made the newspaper in any department but she had her mind made up to write sports and nothing would discourage her. We used to remind her it was too tough for a girl to make it in sports. There was a rule against allowing them in the press boxes. They couldn’t get into the dressing rooms. She was invading a man’s world. With her talent why not go to the city side? Nope, Jeane loved sports and the people in it. It was her world. She conquered it. She put on the gloves with prize fighters and caught the pitches of Bob Feller.

As this article neared completion, Hoffman’s two surviving daughters revisited her legacy. Diane McIntosh’s nine-year-old son was preparing a school report on his grandmother’s career, and Valerie McIntosh, who studied journalism at San Diego State University and later worked in radio, reported finding among her mother’s files a manuscript entitled “No Place for a Lady”—an ironic title given Hoffman’s ability to maintain her feminine identity while thriving in the press boxes, newsrooms, and business offices of the sports media.

JEAN HASTINGS ARDELL lives in Corona Del Mar, California, where she works as a writer, editor, and teacher, with baseball a continuing subject of interest. She is author of “Breaking into Baseball: Women and the National Pastime” (Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), and received the Baseball Weekly/SABR award in 1999.