Babe Ruth and Eiji Sawamura

This article was written by Rob Fitts

This article was published in Spring 2012 Baseball Research Journal

This article was selected for inclusion in SABR 50 at 50: The Society for American Baseball Research’s Fifty Most Essential Contributions to the Game.

Babe Ruth was presented with flowers before a game during the 1934 baseball tour of Japan.

November 20, 1934; Shizuoka, Japan

With a flick of his wrist, the boy received the ball from the catcher. He felt confident as if his opponents were the fellow high schoolers he had shut out just a few months before. The one o’clock sun came directly over Kusanagi Stadium’s right field bleachers, blinding the batters. He knew this. It had enabled him to retire the leadoff batter, Eric McNair, on a pop fly and to strike out Charlie Gehringer. The batters saw his silhouette windup, then a white ball exploded in on them just a few feet away. It was nearly unhittable. Fanning Gehringer thrilled the boy as he saw no flaws in his swing. When facing the Mechanical Man, the pitcher imagined them as samurai dueling to the death with glittering swords. It was a spiritual battle, who could outlast the other—who could will the other to submit. Gehringer, alone among the Americans, showed the spirit of a samurai.

The third batter strode to the plate. He was old—more than twice the boy’s 17 years—and with a sizable paunch, he outweighed the boy by some 100 pounds. His broad face usually bore a smile, accentuating his puffy cheeks and broad nose. His twinkling eyes and boyish, infectious good humor forced smiles even from opponents. Instinctively, the boy looked at his face…this time, a mistake.

There was no friendly smile. The Sultan of Swat glared back like an oni—those large red demons that guard temple gates. The boy’s heart fluttered, his composure lost. Babe Ruth dug in.

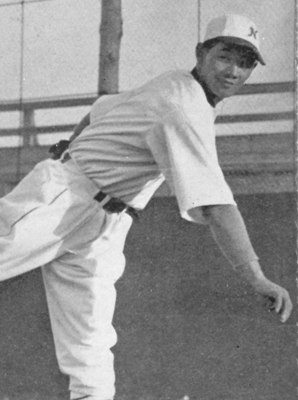

Eiji Sawamura breathed deeply, steadying himself. This was, after all, why he had left high school early and forfeited a chance to attend prestigious Keio University—an opportunity to face Babe Ruth.

Just three months ago, Sawamura had been pitching for Kyoto Commerce High School when Tadao Ichioka, the head of the Yomiuri Shimbun’s sports department, approached his grandfather. Ichioka explained that the newspaper was sponsoring a team of major-league stars, including Babe Ruth, to play in Japan that fall. There were no professional teams in Japan, so Yomiuri was bringing together Japan’s best to challenge the Americans. Ichioka wanted the 17-year-old pitcher on the staff. The newspaper would pay 120 yen ($36) per month, more money than most skilled artisans made. The Sawamura family needed the extra income to support Eiji’s siblings, but the invitation carried a price. The Ministry of Education had just passed an edict forbidding both high school and college students from playing on the same field as professionals. If Sawamura joined the All-Nippon team, he would be expelled from high school and would forfeit his chance to attend Keio University the following semester.

But to pitch against major leaguers! To pitch against Babe Ruth! The boy accepted.1

Sawamura wound up, turning his body toward third base before slinging the ball toward the plate. The blinded Ruth lunged forward, his hips and great chest twisting until they nearly faced the wrong direction. The fastball pounded in catcher Jiro Kuji’s mitt. Strike one.

Sawamura wound up, turning his body toward third base before slinging the ball toward the plate. The blinded Ruth lunged forward, his hips and great chest twisting until they nearly faced the wrong direction. The fastball pounded in catcher Jiro Kuji’s mitt. Strike one.

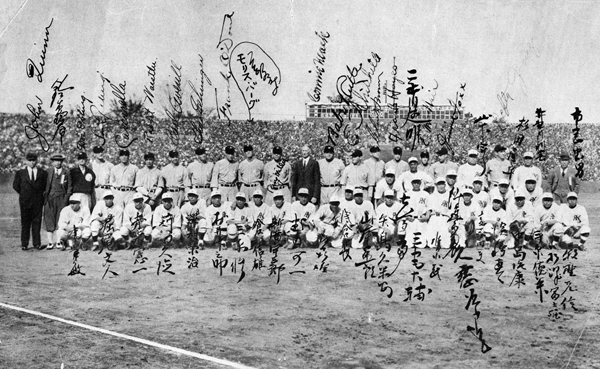

The All-Americans were even better than Ichioka had promised—one of the greatest squads ever assembled. The infield of Lou Gehrig, Gehringer, Jimmie Foxx, and defensive wizard Rabbit Warstler at short would be tough to top. The outfield contained Bing Miller in center, flanked by sluggers Earl Averill and Ruth. Only at catcher was the team weak. Star Rick Ferrell cancelled at the last minute, his spot filled by Philadelphia A’s rookie Frankie Hayes and an amusing fellow named Moe Berg, who did his best to address Sawamura in Japanese. Lefty Gomez led a staff that also included the intense Earl Whitehill and Cleveland hurler Clint Brown. Connie Mack, the grand old man of American baseball, led the team with lovable Lefty O’Doul as his coach.

Baseball exchanges between Japan and the United States had become common by this time. Between 1905 and 1934, more than 35 collegiate, semipro, and professional teams crossed the Pacific. The Chicago White Sox and New York Giants had come to promote the game in 1913; teams that included major leaguers barnstormed in Japan in 1920 and ’22; and a Negro league team known as the Philadelphia Royal Giants played top collegiate teams in 1927 and ’32. In 1931, the Yomiuri newspaper decided to bring over a team of true stars. A squad that included Gehrig and O’Doul, as well as Lefty Grove, Al Simmons, Mickey Cochrane, and Frankie Frisch, had played 17 games against Japan’s best, winning each contest. Although these exchanges created close friendships among Japanese and American players, relations between the nations’ governments were becoming increasingly tense.

After emerging from isolation in 1853, Japan modernized with dizzying speed and began its own policy of colonialism in the 1890s. The bellicose nation defeated China in 1894-95 and Russia in 1904-05 and annexed Korea in 1910. Throughout the 1920s, Japan increased its interests in Manchuria before seizing control of the province in 1931 and creating the puppet state of Manchukuo. Faced with international condemnation, Japan withdrew from the League of Nations in February 1933 and threatened the following year to withdraw from the Washington and London Naval Treaties which limited the size of their navy. As the United States and Japan vied for control over China and naval supremacy in the Pacific, it was apparent that the countries were drifting towards war.

Politicians on both sides of the Pacific hoped that the goodwill generated by Babe Ruth and the two nations’ shared love of baseball could help heal these growing political differences. Many observers, therefore, rejoiced when nearly 500,000 Japanese lined the streets of Ginza to welcome the American ballplayers on November 2, 1934. As the ballplayers traveled by motorcade from Tokyo Station to the Imperial Hotel, rows of fans—often 10 to 20 deep—surged to catch a glimpse of Ruth and his teammates. The pressing crowd reduced the broad streets to narrow paths just wide enough for the limousines to pass. Confetti and streamers fluttered down from well-wishers leaning out of windows and over the wrought-iron balconies of the avenues’ multi-storied office buildings. Cries of “Banzai! Banzai, Babe Ruth!” echoed through the neighborhood as thousands waved Japanese and American flags and cheered wildly. Reveling in the attention, the Bambino plucked flags from the crowd and stood in the back of the car waving a Japanese flag in his left hand and an American in his right.

Finally, the crowd couldn’t contain itself and rushed into the street to be closer to the Babe. Downtown traffic stood still for hours as Ruth shook hands with the multitude. The following day, the New York Times proclaimed: “The Babe’s big bulk today blotted out such unimportant things as international squabbles over oil and navies.” Umpire John Quinn added “on the day the tourists arrived there was war talk, but that disappeared after they had been in the empire twenty-four hours.”2

The All-Americans won each of the first nine games. At first the fans divided their loyalty. Many reveled in seeing former Japanese collegiate stars play on the same team and believed, or maybe just hoped, that they could match the major leaguers. Others came to see the American stars, especially Ruth. Yakyukai, Japan’s top baseball magazine, reported “the fans went crazy each time Ruth did anything—smiled, sneezed, or dropped a ball.” Once the crowds realized their hometown heroes were unlikely to win, most switched allegiance to the visitors—clamoring for home runs. The fans’ enthusiasm impressed and flattered the Americans, helping them overcome cultural differences to develop a deep appreciation for their host country.3

The All-Americans had pounded Sawamura in his first start 10 days earlier on November 10. The 17-year-old remembered how nervous he was before taking the field. It didn’t help when Ruth homered in the first inning, delighting the sold-out Meiji Jingu stadium crowd of 60,000. Sawamura had lasted eight innings, giving up 10 runs on 11 hits, including home runs to Ruth, Averill, and weak-hitting Warstler. But the Japan Times noted that he “pitched courageously to the murderers row” as he struck out both Ruth and Gehrig.4

Fanning Ruth and Gehrig helped the boy grasp that even the greatest had weaknesses. Ruth, for example, had difficulty with knee-high inside curves. As Sawamura told a writer for Yakyukai, “I was scared but I realized that the big leaguers were not gods.” He was noticeably calmer and more effective three days later in Toyama when he relieved Shigeru Mizuhara in the fourth after the starter had surrendered 11 runs. The schoolboy ace held the Americans scoreless until Jimmie Foxx belted a three-run homer in the eighth.5

Recalling how he had struck out Ruth before, Sawamura wound up and fired another fastball.

In 1934, Ruth was no longer the American League’s best player. He was 39 years old and had grown rotund. He knew his career was finished, or at least in its twilight. In August, he announced that he would not return as a full-time player in 1935. The reception in Japan, however, had revitalized the Babe. He reveled in the chants of “Banzai Babe Ruth” and the constant attention. His ego bolstered, his bat responded. After 10 games, the Sultan of Swat had belted ten home runs with a .476 average.

Sawamura’s fastball burst through the glare. The Bambino flailed his 36-inch, 44-ounce Louisville Slugger at the ball, but it was too late. The ball smacked into Kuji’s glove. Strike two.

The sellout crowd at Kusanagi Stadium roared. The park was small, by both American and Japanese standards. Only 8,000 spectators could fit into the grandstands ringing the field. The fans, primarily men, wore light wool overcoats with fedoras or wool driving caps in the pleasant 48-degree afternoon. (Once home, they would remove their western garb, bathe, and don the traditional kimono.) Here and there, however, a man dressed in the traditional manner could be seen in the stands. The fans cheered and shouted on every play, making them louder than an average American crowd. But to the Americans, a familiar sound was missing from the din: no vendors were advertising their wares. No “Hot dogs! Get your hot dogs here!” No “Popcorn!” or “Cracker Jack!” or even the heavenly sound of “Beer! Ice cold beer here!” Eating in the stands was not a Japanese tradition. In fact, eating while walking or sometimes even standing was considered rude. Those who wanted to eat would purchase a small bento (boxed lunch) from an outside vendor or a stand just inside the stadium’s entrance, then quietly eat fish or octopus with rice, or maybe fried noodles with chopsticks.

Both the fans and players noticed differences between American and Japanese baseball. The much smaller Japanese were solid fielders and quick runners but weak hitters. Most still hit off their front foot and hadn’t mastered the hip rotation technique that had enabled Ruth to change the way Americans played the game. They played the field with precision acquired from hours of repetition but without flair—seemingly without joy. John Quinn described them as playing with the seriousness of a professor.6

The Japanese also approached the game differently. They believed that it took more than just natural ability and good technique to win a ball game; it also took a dedicated spirit. Borrowing from a heavily romanticized version of samurai behavior, Japanese players in the 1880s created a distinctive approach to the game. One that emphasized unquestioning loyalty to the manager and team as well as long hours of grueling practice to improve both players’ skills and mental endurance. This “samurai baseball” offered hope to the All-Nippon team. Infielder Tokio Tominaga explained, “Many fans think that the small Japanese can never compete with the larger Americans, but I disagree. The Japanese are equal to the Americans in strength of spirit.”7

With Ruth in the hole, Sawamura knew just what to do. Like any good warrior, he attacked his adversary’s weakness. As he readied himself, the boy twisted his lips in a peculiar fashion. He then raised his arms, kicked his leg high, and fired.

Ruth brought his bat back, raising his rear elbow to shoulder height before taking a short stride with his front foot and snapping his hips forward. The bat followed along a level plane through the strike zone. Just before contact, the ball “fell off the table.” Fooled by the curve, Ruth’s momentum carried him forward, his body twisting around like a corkscrew.

As Ruth walked back to the dugout, a surge of confidence and hope swelled through Sawamura and the crowd. Maybe today would be the day. The Japanese had improved with each game. Both their fielding and pitching were shaper even if their hitting was still weak. Maybe today their fighting spirit would be strong enough to defeat the Americans.

By the next morning, as readers unfurled their newspapers and scanned the headlines, Sawamura had become a national hero. He held the All-Americans hitless into the fourth and scoreless into the seventh, when Gehrig belted a solo home run to win the game 1-0. Although the Japanese had not won, they showed that they were capable of conquering their opponents. Many Japanese felt that with enough fighting spirit their countrymen could surpass the major leaguers, just as they believed their military would surpass the Western powers. As years passed, the duel between Sawamura and Ruth took on greater meaning as the nations battled in the Pacific.

The All-Americans stayed in Japan for a month, winning all 18 of their games. Many declared the tour a diplomatic coup and marveled over Ruth’s success as an ambassador. “Ruth Makes Japan Go American” proclaimed The Sporting News.8 Connie Mack summed up the consensus that the trip did “more for the better understanding between Japanese and Americans than all the diplomatic exchanges ever accomplished.” Soon after the All-Americans returned, Mack told reporters, “When we landed in Japan the American residents seemed pretty blue. The parley on the naval treaty was on, with America blocking Japan’s demand for parity. There was strong anti-American feeling throughout Japan over this country’s stand. Things didn’t look good at all and then Babe Ruth smacked a home run, and all the ill feeling and underground war sentiment vanished just like that!”9

A month later at the 12th Annual New York Baseball Writers’ Association meeting, Mack told the assembly, “that there would be no war between the United States and Japan, pointing out that war talk died out after his All-Star team reached Nippon.”10 Many Americans wanted to believe Mack. With the isolationist movement dominating foreign policy and national sentiment, Americans eagerly seized on signs of peace, turning a blind eye to Japan’s increasingly aggressive military.

Of course, the war that could never be eventually came. Babe Ruth was in his 15th-floor Manhattan apartment on December 7, 1941 when he heard the news. For the Babe, Pearl Harbor was a personal betrayal. Cursing the double-crossing SOBs, he heaved open the living room window. His wife Claire had decorated the room with souvenirs from the Asian tour—porcelain vases, plates, exquisite dolls. The Babe stormed to the mantle, grabbed a vase and heaved it out the window. It crashed on the street below. Other souvenirs followed as Ruth kept up a tirade about the Japanese. Claire rushed around the room, gathering up the most valuable items before they joined the pile on Riverside Drive.11

The Sultan of Swat knew how to take revenge. Using the same charisma that made him an idol in Japan, he threw himself into the war effort, raising money to defeat the Japanese and their allies. Ruth worked closely with the Red Cross, making celebrity appearances, playing in old-timers games, visiting hospitals, and even going door-to-door seeking donations. He became a spokesman for war bonds, doing radio commercials, print advertisements, and public appearances to boost sales, and even bought $100,000 worth himself.

Perhaps the Babe’s most publicized event came on August 23, 1942, when 69,136 fans packed Yankee Stadium to watch Ruth play ball for the first time in seven years. The 47-year-old Babe faced 54-year-old Walter Johnson in a demonstration before an old-timers game. Johnson threw 15-20 pitches and the Bambino hit the fifth one into the right-field stands. In the hyperbolic style of the time, sports columnist James Dawson wrote, “Babe Ruth hit one of his greatest home runs yesterday in the interest of freedom and the democratic way of living.”12 The event raised $80,000 for the Army-Navy relief fund. Ruth’s biographer Marshall Smelser concluded that “Ruth … had become a patriotic symbol, ranking not far below the flag and the bald eagle.”13

*****

The attack on Pearl Harbor did not surprise or upset Eiji Sawamura. On December 7, 1941, Sawamura sat in a staging area on the Micronesian island of Palau awaiting orders. Soon, he would board a crowded transport as part of a massive assault group. He did not know where he would land, but he hoped that he would get to fight the Americans, whom at this point he considered to be little more than animals.14

After the tour, Sawamura and most of the All-Nippon players signed pro contracts with the newly-created Yomiuri Giants. The Giants toured the U. S. before participating in the inaugural season of the Nippon Professional Baseball League in the Fall of ’36. Sawamura was the circuit’s top pitcher, leading the league in wins that year, then capturing the MVP award in ‘37. On July 7, 1937, after Eiji finished a one-run complete game, Japanese troops provoked a skirmish at the Marco Polo Bridge, setting off the Second Sino-Japanese War. The conflict would last eight years, cause over 22 million casualties, and spiral into World War II.

Eiji received a draft notice in January 1938 and was assigned to the 33rd Infantry Regiment of the 16th Division. Most of the regiment was currently in Nanking, becoming notorious as “the most savage killing machine among the Japanese military units.”15 Sawamura’s 33rd Regiment was at the center of the atrocities against both civilians and prisoners of war during “The Rape of Nanking” and would become one of the perpetrators of the notorious Bataan Death March.

Like most Japanese, Sawamura supported his country’s military expansion and did not question the decision to go to war. Since 1890, when the Meiji government announced the Imperial Rescript on Education, all Japanese school children had been trained to obey the Emperor and state. American Ambassador to Japan Joseph Grew told readers in his 1942 book Report from Tokyo, “In Japan the training of youth for war is not simply military training. It is a shaping…of the mind of youth from the earliest years. Every Japanese school child on national holidays … takes part in a ritual intended to impress on him his duties to the state and to the Emperor. Several times each year every child in taken with the rest of his schoolmates to a place where the spirits of dead soldiers are enshrined. … Of his obligation to serve the state, especially through military service, he hears every day. … The whole concept of Japanese education has been built upon the military formula of obeying commands.”16

As a result of this education, most Japanese believed that the Western powers were not only thwarting Japan’s right to control Asia through the so-called Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere but were also unfairly strangling the nation through oil and material embargoes. When Japanese radio announced the attack on Pearl Harbor, “the attitudes of the ordinary people,” according to literary critic Takao Okuan “was a sense of euphoria that we’d done it at last; we’d landed a punch on those arrogant great powers Britain and America, on those white fellows. … All the feelings of inferiority of a colored people from a backward country, towards white people from the developed world, disappeared in that one blow… Never in our history had we Japanese felt such pride in ourselves as a race as we did then.”17

Whereas most of the All Americans finished the 1934 goodwill tour with warm feelings toward Japan, Sawamura had grown to hate Americans. His loathing began during the Yomiuri Giants’ first visit to the United States in 1935. Just before returning to America in 1936, a piece by Sawamura entitled “My Worry” appeared in the January issue of Shinnseinen. He wrote: “As a professional baseball player, I would love to pitch against the Major Leaguers, not just in an exhibition game like I pitched against Babe Ruth, but in a serious game. However, what I am concerned about is that I hate America, and I cannot possibly like American people, so I cannot live in America. Firstly, I would have a language problem. Secondly, American food does not include much rice so it does not satisfy me, so I cannot pitch as powerfully as I do in Japan. Last time I went to America, I could not pitch as well as I do in Japan. I cannot stand to be where formal customs exist, such as a man is not allowed to tie a shoelace when a woman is around. American women are arrogant.”18

Eiji completed his basic training and joined his regiment in Shanghai. Soon after his arrival, the 33rd joined an offensive against Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist army. Relying on his baseball skills, Sawamura became renowned for his grenade throwing and was often given the task of cleaning out strong Chinese positions with a difficult toss. But in September 1938 he took a bullet in his left hand. He spent an undisclosed amount of time in a military hospital before being discharged in October 1939.19

Sawamura took the mound again for the Yomiuri Giants during the 1940 season, but throwing heavy grenades had damaged his arm, limiting him to a sidearm motion. He no longer had the velocity of his pre-service years but he remained crafty, tossing a no-hitter against the Nagoya team on July 6. It was the third no-hitter of his career, but it lacked the luster of his first two as the war in China had depleted the pro baseball rosters. Five no-hitters were thrown in 1940, more than any other season in Japanese pro baseball. Eiji finished the 1940 season with a seemingly strong 2.59 ERA, but in truth, his mark fell well above the league ERA of 2.12.

As the military furthered their control of Japan in the late 1930s, the movement to cleanse Japan of Western influence and trappings strengthened. Pulitzer-prize winning historian John Dower has shown that Japanese of the 1930s and 40s did not necessarily see themselves as physically or intellectually superior, but they did view themselves as more spiritually virtuous than others.20 Propaganda of the time focused on the development of a pure Japanese spirit, Yamato Damashii.

This entailed a return to traditional Japanese life ways, emphasis on self-denial and self-control, and reverence for the Emperor. Western influences were viewed as corrupting, as they emphasized individuality and undermined Japanese culture and spirit. Army General Sadao Araki, for example, proclaimed, “frivolous thinking is due to foreign thought.”21 Imported amusements fell out of fashion. By the mid-1930s, military marches had replaced jazz as the most popular music. During the war, jazz would be outlawed and even musical instruments used in jazz, such as electric guitars and banjos, were banned.

In the late 30s, the Ministry of Education decreed that scholastic sports should be stripped of “liberal influences” and replaced with traditional Japanese values and physical activities designed to enhance national defense. In 1940, Nippon Professional Baseball’s board of directors followed suit. They declared that all games would be played following “the Japanese spirit” and banned English terms. Henceforth, the game would only be known as yakyu (field ball) and not besuboru. “Strike” would now be “yoshi” (good), and “ball” became “dame” (bad).

Other English terms were also replaced with Japanese equivalents. Team nicknames, such as Giants and Tigers, were abandoned. Yomiuri became known as Kyojin Gun (Giants Troop) and the Hanshin Tigers became Moko Gun (the Fiery Tiger Troop). Two years later (1942), uniforms were changed to khaki, the color of national defense, and baseball caps were replaced with military caps.22

Not surprisingly, Babe Ruth was no longer revered. The jovial, overweight, self-indulgent demi-god of baseball became a symbol of American decadence. In 1944, Japanese troops were screaming, “To hell with Babe Ruth!” as they charged to their deaths across the jungles of the South Pacific. The Babe’s response to the insult was classic Ruth, “I hope every Jap that mentions my name gets shot—and to hell with all Japs anyway!” He then took to the streets to raise money for the Red Cross telling reporters that he was spurred on by the Japanese war cry.23

Although still hampered by his damaged arm, a continuing bout with malaria, and difficulty sleeping, Sawamura threw 153 innings for Yomiuri during the 1941 season. He was no longer a top pitcher. His 2.05 ERA was the highest of the team’s five regular pitchers and was .19 runs above the league average. Just before the end of the season, Eiji married his long-time girlfriend Ryoko, but marital bliss was short-lived. Only three days later, Sawamura received a second draft notice. He was to report immediately to the 33rd Regimental headquarters. Units across Japan were being mobilized on the double.24

The 33rd left Nagoya on November 20, 1941 (the seventh anniversary of his near-win against the All-Americans) and headed by transport to the island of Palau in Micronesia, where they joined a 130,000-strong invasion force. In early December, the 33rd split. The second and third Battalions left with the majority of the assembled troops, while Sawamura and his first Battalion remained on Palau. On the night of December 16, Sawamura and his comrades boarded a transport and set sail for the Philippines.

As the main body of the invasion force attacked the island of Luzon and pushed toward Manila, Sawamura’s force invaded the city of Davao on the island of Mindanao. They occupied the city without a fight as the outnumbered American/Filipino garrison withdrew. Davao was the only area in the Philippines with a significant Japanese population; nearly 20,000 had immigrated to work on the nearby hemp plantations. With Davao secured, the Japanese pushed into the surrounding jungles in pursuit of the American and Filipino troops. The Allies retreated before the superior Japanese force, only to mount swift counter-attacks when they spotted a weakness. Sawamura found such behavior dishonorable and cowardly. “When we were strong and solid, the western devils got quiet as a cat. But, when they saw that we were not prepared, they would attack like a cruel evil.” To Sawamura’s shock, the outnumbered Americans soon surrendered. “They surrendered immediately even if they had enough bullets and guns,” he later wrote with disgust. “While Japanese put their hands up in the sky in a banzai cheer at victory, Americans put their hands up in a halfway manner shamelessly as soon as they realized that they could not win and there was no way out.”25

As Sawamura’s First Battalion fought in Mindanao, the rest of his regiment and division had just defeated the main American force at the Battle of Bataan. The Japanese took 75,000 American and Filipino prisoners and force-marched them 60 miles through tropical jungles without water or food. Stragglers were killed. Escorting Japanese, including members of Sawamura’s regiment, beat, shot, and beheaded prisoners for sport as they traveled by the winding column. Over a quarter of the prisoners died before they reached an internment camp at Capas. Known as the Bataan Death March, the incident became one of the most famous atrocities committed by the Japanese army.

Sawamura stayed in the Philippines for just over a year, returning to Japan with his regiment in January 1943. He rejoined the Yomiuri Giants for the 1943 season, but three years in the Imperial Army had taken its toll. His famous control was gone. Eiji pitched just 11 innings, giving up 17 hits and walking 12. He finished out the season as a pinch-hitter.

No longer a soldier, Sawamura capitalized on his baseball fame to support the war effort. In November 1943, he published a nine-page article about his combat experiences in the baseball magazine Yakyukai.26 Articles supporting the war effort were common in Japanese magazines. Unlike the Nazis or Soviets, who had centralized bureaus responsible for propaganda, in both Japan and the United States private enterprises willingly created propaganda to boost morale on the home front.27

The piece includes themes common in most Japanese propaganda. Sawamura depicts both the suffering and daily toil of military life to remind readers that self-sacrifice was the moral obligation of all Japanese to support the war effort. Civilians were expected to bear their difficulties without complaint as the military faced the true hardships. He praises the uniqueness of the Japanese spirit, emphasizing the virtues of self-sacrifice, respect, and duty. Following a universal theme of wartime propaganda, Sawamura depicts the enemy as cruel, demonic savages.

One particularly unbelievable story has the American garrison of Davao gathering the entire Japanese population of 20,000 in basements rigged with mines. The Americans, according to Sawamura, were planning on blowing up the prisoners before the Imperial Army entered the city but the speed of the Japanese advance startled the Americans and caused them to retreat before setting off the explosives.

Another story, which Sawamura admits he did not witness, has American soldiers executing prisoners by pouring boiling water over their heads. With Sawamura’s popularity and Yakyukai’s wide circulation, thousands, if not millions, read the article. Just as Babe Ruth was using his popularity to support the America war effort, Japan’s great diamond hero did what he could to support his nation. Sawamura, however, would ultimately give more than the Bambino.

Before the start of the ‘44 season, the Giants decided not to renew Sawamura’s contract. Devastated, Eiji announced his retirement. In October, another letter arrived from the Imperial Army. The 33rd was being reactivated and sent into combat. By the fall of 1944, the tide of the war had turned against the Japanese. The Battle of Midway in June 1942 had crippled the Japanese Navy allowing the Allies to begin their offensive. In the spring and summer of ’44, Americans captured Saipan, Guam, and Palau and readied to retake the Philippines. On October 20, 1944, 200,000 American forces, commanded by General Douglas MacArthur, landed on Leyte to begin the campaign. The Imperial Army’s 16th Division, Sawamura’s old combat group, defended the area. Heavily outnumbered, the Japanese rushed reinforcements to the area.

The 33rd left Japan on November 27 and steamed toward the Philippines, but Sawamura never reached his destination. On December 2, an American submarine incepted his transport off the coast of Taiwan and sank it. The hero of the 1934 goodwill tour was dead, killed by the creators of the game he loved.

After his death, Eiji Sawamura became an icon of Japanese baseball. In 1947, the magazine Nekkyo created the Sawamura Award to honor the best pitcher in Nippon Professional baseball. Twelve years later, he became one of nine initial members of the Japan Baseball Hall of Fame. Later, statues of the pitcher would be raised outside Shizuoka Kusanagi Stadium and his old high school in Kyoto. Sawamura’s image would also be placed on a Japanese postal stamp. Many consider him to be the country’s greatest pitcher. But in truth, he was only a standout pitcher for two years. Why then, was he elevated to the pantheon of immortals?

In his short life, Sawamura personified the trials of his country. In 1934, as Japan strove to be recognized as an equal to the United States and Britain, he nearly overcame the more powerful American ballclub. Many viewed his performance as an analogy of Japan’s struggles against the west—with the proper fighting spirit Japan could overcome their rivals. In late 1930s and early 1940s, Japan and Sawamura went to war. Eiji wholeheartedly supported the war effort, both as a soldier and spokesman. The press updated fans on his life at the front and upheld him as a patriot who sacrificed his career and endured hardships to serve his Emperor and country.

After the war, Sawamura’s life took on a different meaning. Many Japanese felt betrayed by their leaders for initiating a futile war that destroyed their country and lives. To help reconcile the two nations, American occupational forces propagated the myth that a cadre of military extremists had pushed Japan into an unwanted conflict. This enabled the Japanese populace to view themselves as victims of wanton militarism and a repressive government.28 Sawamura came to symbolize an entire generation whose dreams and lives were shattered by evils of war.

Eiji Sawamura had become more than a ballplayer. Like Babe Ruth, he had become a national symbol.

ROBERT K. FITTS graduated from the University of Pennsylvania and received a Ph.D. from Brown University. Originally trained as an archeologist of colonial America, Fitts left that field to focus on his passion, Japanese baseball. He founded the SABR Asian Baseball Research Committee. He is also the author of “Remembering Japanese Baseball: An Oral History of the Game” (winner of the 2005 Sporting News-SABR Baseball Research Award), “Wally Yonamine: The Man Who Changed Japanese Baseball,” and “Banzai Babe Ruth: Baseball, Espionage & Assassination during the 1934 Tour of Japan.”

Sources

This narrative on the November 20, 1934 game is based on Japan Times November 21, 1934;5; Osaka Mainichi November 21, 1934; Sotaro Suzuki, Sawamura Eiji: The Eternal Great Pitcher in Japanese] (Tokyo: Kobunsha, 1982):75-7; Yakyukai 25, no. 1 (1935): 160-1; Yomiuri Shimbun November 20, 1934:5.

Notes

1 Sotaro Suzuki, Sawamura Eiji: The Eternal Great Pitcher in Japanese] (Tokyo: Kobunsha, 1982): 65-75.

2 New York Times, November 3, 1934; Spalding, Spalding Official Base Ball Guide 1935, 264.

3 Yakyukai 25, no. 3 (1935): 184.

4 Japan Times, November 11, 1934: 1.

5 Yakyukai 25, no. 1 (1935): 160-1.

6 John Quinn, “Radio Address on NBC November 9, 1934.” John Quinn Scrapbook, private collection.

7 Yakyukai 25, no. 1 (1935): 138.

8 The Sporting News, November 15, 1934: 3.

9 Daily News (New York) January 7, 1935: 34.

10 The Sporting News, February 7, 1935:1.

11 Interview with Julia Ruth Stevens, November 7, 2007.

12 Dawson quoted in Robert Elias, The Empire Strikes Out (New York: The New Press, 2010). 137.

13 Marshall Smelser, The Life that Ruth Built (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1975): 525-7; Gary Bedingfield, “Babe Ruth in World War II,” Baseball in Wartime (www.baseballinwartime.com, accessed March 17, 2010).

14 Eiji Sawamura, “Memoirs of Fighting Baseball Player [in Japanese],” Yakyukai 33, no 11 (1943): 92-100.

15 Masahiro Yamamoto, Nanking (New York: Praeger, 2000), 92.

16 Joseph Grew, Report from Tokyo (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1942), 51.

17 Quoted in Ian Buruma, Inventing Japan, 1853-1964 (New York: The Modern Library, 2003), 111.

18 Eiji Sawamura, “My Worry [in Japanese],” Shinnseinen (January 11, 1936): 258-9.

19 Sotaro Suzuki, Sawamura Eiji: The Eternal Great Pitcher in Japanese] (Tokyo: Kobunsha, 1982).

20 John Dower, War Without Mercy (New York: Pantheon Books, 1986): 203-233.

21 Harry Emerson Wilde, Japan in Crisis (New York: Macmillan, 1934): 52.

22 The Sporting News, November 7, 1940: 10; Joseph Reaves, Taking in a Game: a History of Baseball in Asia (Lincoln: Bison Books, 2004), 78-9; Ian Buruma, Inventing Japan, 1853-1964 (New York: The Modern Library, 2003), 93; Ikuo Abe, Yasuharu Kiyohara, and Ken Nakajima, “Sport and Physical Education Under Fascism in Japan,” Yo: Journal of Alternative Perspectives (June 2000); Masaru Ikei, White Ball Over the Pacific in Japanese] (Tokyo: Chuokoron, 1976); Ben-Ami Shillony, Politics and Culture in Wartime Japan (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981), 144.

23 New York Times, March 3, 1944:2; New York Times, March 5, 1944: 37.

24 Sotaro Suzuki, Sawamura Eiji: The Eternal Great Pitcher in Japanese] (Tokyo: Kobunsha, 1982).

25 Eiji Sawamura, “Memoirs of Fighting Baseball Player [in Japanese],” Yakyukai 33, no 11 (1943): 92-100.

26 Ibid.

27 For discussion of Japanese wartime propaganda see Barak Kushner, The Thought War (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007) and John Dower, War Without Mercy (New York: Pantheon Books, 1986).

28 James J. Orr, The Victim as Hero (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2001).