The Chicago Cubs’ College of Coaches: A Management Innovation That Failed

This article was written by Rich Puerzer

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 26, 2006)

P.K. Wrigley and the Chicago Cubs’ “College of Coaches” in 1961. (ASSOCIATED PRESS)

In any business venture, management often seeks to make changes in everyday operations in order to bring about improvements in overall performance. These changes may range from minor tweaks in normal operating procedures to overhauls of the conventional methods in place.

The same is true in professional baseball. Minor management changes may include rearranging the batting order or perhaps the reapportionment of playing time. When a major change in team direction is desired, it often involves the replacement of the manager.

Following the 1960 baseball season, Chicago Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley wished to make a significant change in how his team operated. Team performance warranted such a change, as the Cubs finished in seventh place, having won 60 and lost 94 games, ending up 35 games out of first place. Wrigley wished to change the direction of his team while also expediting the development of players in the Cubs’ minor league system. The method he developed and implemented for bringing about this change was revolutionary and radical, defying all previous baseball convention. His idea was to essentially do away with the position of manager, a position which had existed on virtually all professional baseball teams for nearly a century, while increasing the number and changing the roles of his coaches.

On January 12, 1961, at the annual hot stove press luncheon of the Chicago Cubs, Wrigley made several announcements that grabbed the attention of the baseball world. He stated that in 1961 the Cubs would operate without a manager “as that position is generally understood;’ that the eight-man coaching staff would take turns directing the major league team, and that those same coaches would also rotate through the Cubs’ minor league system.1 Thus began what became known as the Chicago Cubs’ college of coaches.

The Cubs would operate using the college of coaches scheme for the 1961 and 1962 seasons, and continued to utilize aspects of it through 1964. These tumultuous years would prove that the primary idea behind the college of coaches, to operate without an individual manager on the major league level and to regularly rotate the responsibilities of coaches throughout all levels of the organization, was a failure. However, there were also positive outcomes resulting from this innovative approach to baseball management. The following is an examination of the ideas behind, and the implementation and the results of, the Chicago Cubs’ college of coaches.

Philip K. Wrigley

Philip K. Wrigley assumed ownership of the Cubs in 1932 when, upon the death of his father William Wrigley, he inherited the team. He retained owner ship of the team until his own death in 1977.2 During his long tenure as owner, Philip Wrigley’s enigmatic leadership approach wavered between innovation and a rigid adherence to the status quo.

Although Philip Wrigley is best known for success fully continuing the business ventures started by his father, he was an extremely successful, ambitious, and often innovative businessman in his own right. He was one of the forefathers of commercial aviation in the United States, helping to start the company that would become United Airlines.3 He was also success fully involved in the banking and hotel industries. And of course he led the Wrigley Company, synonymous with chewing gum, following in the footsteps of his father. He continued his father’s success in the chewing gum business, aided greatly by his own ground breaking ventures at the forefront of radio, and later advertising.

During World War II, Wrigley appealed to patriotic efforts by utilizing advertising relating the chewing of gum to increased efficiency on the job. He also worked closely with the government while still promoting his product. Wrigley’s gum was included in army rations, which themselves were packed in Wrigley plants.4 Efforts such as these made Wrigley’s gum ubiquitous throughout the world and allowed the company to not only survive but to flour ish in these economically difficult times. Innovative thinking such as this was also evident on occasion in Wrigley’s approach to the management of the Cubs.

At times Wrigley was quite revolutionary in his approach to baseball management. In 1938, he hired Coleman R. Griffith, a pioneer in the nascent field of sports psychology, as a consultant to the team. Griffith stayed with the team for two years and pursued many new methods for the analysis of the game in an attempt to build a scientific training program for the team. His work included such techniques as filming players, recommending improved training regimes, the documentation of player progress through charts and diagrams, and changes in batting and pitching practice in order to make the practice sessions more closely resemble game conditions.

However, Griffith suffered through rancorous relationships with the two Cub managers he worked with, Charlie Grimm and Gabby Hartnett, and had much of his work undermined by these men. In the end, although he produced over 400 pages of reports, including documentation on the use of novel methods and measures later used throughout professional baseball, his work was for naught.5

At other times Wrigley was very traditional in his approach to the management of the team. He was often inclined to loyalty, hiring former Cub players to be manager, including Gabby Hartnett, Charlie Grimm, Stan Hack, and Phil Cavarretta.

Although he participated in the operations of the team, including personnel decisions, he claimed to defer to the judgments of his baseball men in the evaluation of talent.6 Still, he was often criticized for not attending many games and instead focusing his attention on the operations of the chewing gum company.7

The one decision which drew the most fire of critics, and arguably had a deleterious effect on the performance of his team, was his refusal to install lights at Wrigley Field. Unlike every other team in major league base ball after 1948, the Cubs played only day games at home. Whether or not playing day games exclusively provided the Cubs with a home field advantage or hurt the team, clearly it was an indication of Wrigley’s often inscrutable approach to the management of his baseball team.

Despite the quote attributed to Wrigley, “Baseball is too much of a sport to be a business and too much of a business to be a sport,” he made considerable efforts in trying to apply a business approach to the management of the Cubs.8 The college of coaches system was clearly inspired by the business world and was certainly innovative in baseball. No team had gone without a field manager, a single leader with the authority over, responsibility for, and the accountability for his team’s performance in the history of professional baseball.

The Performance of the Cubs: 1945-1960

During the early years of Wrigley’s tenure as owner, the Cubs had experienced a fair amount of success, winning the National League pennant in 1932, 1935, and 1938. In 1945, the team won 98 games and the National League pennant, but lost the World Series to the Detroit Tigers. In 1946, the Cubs won 82 games and finished third in the National League. Following 1946, however, the Cubs would not finish over .500 for 14 straight years, including nine seasons when they would finish in last or second to last place in the National League.9

In these 14 years of futility, the Cubs employed six managers. All but one of these managers was given at least one full season to improve the play of the team. The lone manager that was given less than a full season to manage was Lou Boudreau, who managed only a part of the 1960 season.

The Cubs’ managerial situation immediately prior to 1961 foreshadowed the emergence of the college of coaches. Bob Scheffing managed the team through the 1957, 1958, and 1959 seasons. Despite improvements in the number of wins each season and a good relationship with his players, Scheffing was replaced prior to the 1960 season by Charlie Grimm. He had served as Cub manager twice previously, leading the team to the 1945 pennant. A favorite of Philip Wrigley, Grimm managed only the first 17 games of the season, with the team going 6-11, before he traded jobs with then Cub radio broadcaster Lou Boudreau. Although Boudreau was certainly a seasoned manager, with 15 years of experience under his belt, this switching of roles of broadcaster and manager was unprecedented and certainly unorthodox.

In 1960, the Cubs finished with a record of 60 wins and 94 losses, good for seventh place in the National League, 35 games behind the league-leading Pittsburgh Pirates. Following the season, Wrigley denied Boudreau’s request for a two-year contract and supported his return to the radio booth.10 Thus, the position of manager was once again open.

Clearly the poor performance of the Cubs in the years leading up to the implementation of the college of coaches was strong motivation for the development of the system. The failings of the Cubs during this time were limited to neither the managers nor the many players filling the roster. The problems were systemic; including failures in scouting players, training players at the minor league level, and in organizational decision making. So, in seeking to change team performance, Wrigley decided to not just hire a new manager but to devise a plan to change the club’s system of management, and approach to player development, on all levels of the organization.

The College of Coaches

The original concept of the college of coaches was probably an assemblage of several ideas. Elvin Tappe, who had served as a backup catcher for the Cubs in the late 1950s and early ’60s, claims to have approached Wrigley with the idea of rotating coaches on the minor league level. His suggestion was to have hitting, pitching, and fielding instructors who would rotate around the minor league teams so as to provide uniform instruction to developing players. Tappe pointed out that minor league teams were often managed and/or coached by former pitchers who might not be able to understand the needs of position players or provide the requisite instruction in batting. Tappe’s rotating-coach idea would solve this problem by providing specialized instruction to all players.

However, Tappe stated, “I never intended it to be used on the big league level,” and that “Mr. Wrigley got all carried away.”11 Tappe’s scheme would later become commonplace in professional baseball, with specialized roving instructors working throughout the minor league systems of every major league team.12

There was clearly a business aspect implicit in the implementation of the college of coaches as well. At the press conference in which Wrigley made his initial justification of the system, he discussed in detail his discomfort with the word “manager.” He equated the meaning of the word with that of the word “dictator” and made it clear that “he did not want a dictator.”13

Wrigley illustrated the manner by which managers were, and essentially still are, employed in the major leagues. He pointed out that when a team performs poorly, the manager is made the scapegoat and is often fired. This led him to question the importance of managers given the rate with which they were replaced. He pointed out that managers must be relatively interchangeable given that in the period from 1946 to 1960, 103 managers had been replaced on the major league level.14

Additionally, he equivocated that the job of managing a baseball team, like that of the presidency of the United States, is too much for one man. Wrigley also pointed out that this team-based approach to leading a ball club was similar to the methods employed by his gum company, and that no one manager was too important to be replaced either due to necessity or preference. In the end, however, Wrigley clarified the essence of the motivation for the change in stating, “We certainly cannot do much worse trying a new system than we have done for many years under the old.”15

As time passed after Wrigley’s initial announcement, it became clear that the college of coaches approach was designed not just to change how the management of the major league team would be accomplished. Wrigley also planned to rotate all of the coaches through the minor league system in hopes of improving and expediting the development of minor league players. This would be accomplished through the training and instruction of players by major league-caliber coaches.

Wrigley pointed out that in football, a cadre of specialized coaches was utilized to improve team performance. He believed that this approach could be just as applicable in baseball.16 He was also seeking to make uniform the instruction that minor league players received as they ascended through the farm system. Wrigley pointed out that in the current system, minor leaguers “have been transients through several farm clubs and at each new place they receive conflicting advice and coaching.”

Wrigley announced that eight to 14 coaches would make up the system, and that all of the coaches would be considered equal, and would receive similar salaries of $12,000 to $15,000 a year.17 Overall, the many changes brought about by the college of coaches were designed to improve the Cubs on the major league level and to make them a competitive ball club. Wrigley termed his approach “business efficiency applied to baseball.”18

Computerization

Another pioneering approach that Wrigley sought to use in concert with the college of coaches was the use of computers for statistical analysis. Wrigley brought several IBM computer cards with him to display at the press conference used to introduce the idea of the college of coaches. The initial application of the technology was to calculate and track the batting averages of Cub hitters against individual opposing pitchers and likewise monitor Cub pitchers’ performance against hitters.

Wrigley stated that the data the team would track was not new, but that the availability of the information would be expedited through the use of the computer allowing for it to be used in a more timely fashion.19 In doing this, the Cubs were most likely the first major league team to utilize computer technology.20

The utilization of computers was met with skepticism by the press. One writer described it as a tool for providing “modern, if slightly mad, decisions.”21 Another marveled at the possibility of turning to a computer in the dugout and querying the machine as to what strategies to employ. Overall, the Cubs’ use of computers was generally scoffed at, although in retrospect they were clearly on the leading edge of data analysis in the baseball world.

Reaction to the College of Coaches Concept

Initial reaction to the college of coaches approach ranged from curiosity to derisive criticism. The press developed a number of names mocking the group of rotating coaches including: the college of coaches, the braintruster bloc, the knights of the Cubs’ roundtable, the enigmatic eight, the double-domed thinkers, and the nine-headed manager. Although the approach generally became known as the Cubs’ college of coaches, Wrigley usually referred to it as the “management team”

John Carmichael of the Chicago Daily News, a longtime critic of Wrigley, saw the college of coaches idea as an ulterior motive and means for reviving both Wrigley’s and the fans’ interest in the Cubs.22 Meanwhile, a writer for the Los Angeles Times belittled Wrigley’s efforts, comparing him to “the scientists who are trying to put a man on the moon when they could benefit humanity a whole lot more by discovering a preventative for hangovers.”23

The Cubs’ coaching situation even drew the attention of President John F. Kennedy. In a speech on the introduction of automation and the potential problems it presented in terms of unemployment, Kennedy observed, “Chicago, I might add, also provides the exception to this pattern — since it now takes ten men to manage the Cubs instead of one!”24

One voice in support of Wrigley’s innovative approach was found on The Sporting News’ editorial page, applauding his “refusal to conform” and stating that they were eager to see how the “experiment” progressed.25 Another supportive, although anonymous, voice was found at the Chicago Tribune, expressing that Wrigley deserved “great credit for trying to overcome his baseball problems in the same calm spirit that he applies to chewing gum problems” and that perhaps he would prove to be the “Einstein of the game.”26

Overall, however, the press was quite critical. Or, as Wrigley would put it: “Newspapers from coast to coast were filled with columns and columns of misinformation, cockeyed speculation, derision, and outright condemnation, none of which is based on a shred of information to what our plan was, but only on the fact that we were going to try something new.”27

Former major leaguer Fred Lindstrom was so moved by the news of Wrigley’s idea that he wrote to New York Times sportswriter Arthur Daley stating that it was clear to him that Wrigley “had never been exposed to the value of a truly great leader like John McGraw.” Daley, in reflecting on the idea of the college of coaches, remarked rather presciently that the Cubs “may be the most coached and least managed team in baseball.”28

Cub players were initially positive, at least to the press. Richie Ashburn was quoted as saying that the “plan for the minors is really good,” although he also admitted to some confusion regarding the overall idea.29 An interesting, although cynical, perspective on the college of coaches was offered by an opposing player. Jim Brosnan, Cincinnati Reds relief pitcher and author of Pennant Race, a diary of sorts of the Reds’ 1961 season, remarked that “the psychological aspects of Chicago-style management were admirable” and that “any player who did not like his manager at the start of the year could wait patiently, aware that a change, maybe for the better, was just around the next losing streak.”30

The First Year of the College of Coaches

The initial cadre of nine coaches selected to lead the Cubs were Bobby Adams, Rip Collins, Harry Craft, Vedie Himsl, Charlie Grimm, Goldie Holt, Fred Martin, Elvin Tappe, and Rube Walker. Tappe, Craft, and Himsl had all served the Cubs as coaches the previous year; Grimm had just served as Cubs’ manager and announcer; Walker had worked in the Cub farm system for several years; and Collins, Holt, Martin, and Adams were new to the organization. Also, veteran player Richie Ashburn was assigned as the player representative working with the coaches. During spring training, the initial scheme was for each of the coaches to serve as head coach in the squad games using an alphabetical-order rotation.31

After the team was at spring training and media scrutiny continued, Wrigley continued to defend the new system. On March 17, the team issued a 21-page booklet, titled The Basic Thinking That Led to the New Baseball Set-Up of the Chicago National League Ball Club, to the baseball writers covering the team.32 Each booklet was numbered so as to ensure that all copies would be returned to the team. Sadly, no copies of this booklet appear to still exist. However, a great deal of its contents was included in the newspaper stories on the Cubs.

In the booklet Wrigley continued to assert, “To achieve more and better instruction, we need coaching specialists in the various baseball skills and we can’t have them dominated by somebody with a one-track mind, which is what a man with the title of manager usually turns out to be.” Likewise, Wrigley wrote, ”Analyzing our own situation and the failure of every type of manager, from the hard bitten slave-driver to the inspirational leader, to move the team into a contending position in the last 14 years, we can conclude that individually and collectively the problem is the same for everyone-namely a lack of sufficient amount of quality talent.”

He also pointed out that expansion in baseball makes these issues all the more critical, as the pool of talent will be spread more thinly among a larger number of teams. After expansion, Wrigley clarified, the number of major league players will increase from 400 to 500 players. Wrigley then pointed out, “It is obvious an accelerated program of development is an absolute necessity to meet our commitments and that it is essential to have more instruction of big league quality in order to turn raw material into the finished product at the fastest rate possible.” Wrigley closed by making it clear that the Cubs’ goal was to “take the major league club and loosely knit organization of minor league clubs and weld the whole thing into one compact organization, where everyone is of equal importance to our ultimate goal.”33

Towards the end of spring training, the initial assignment of coaches was determined. Bobby Adams, Harry Craft, El Tappe, and Vedie Himsl were to serve as the initial rotating group of head coaches with the major league team. Meanwhile, Charlie Grimm, Gordie Holt, and Fred Martin would serve as roving instructors throughout the farm system; and Rip Collins, Lou Klein, and Rube Walker were assigned to manage in the farm system. The season began with the naming of Vedie Himsl as the first head coach of the Cubs. Avitus ”Vedie” Himsl, 44, was a career minor league pitcher, and had been with the Cubs since 1952. However, his only managerial experience was two years at the helm of the Cubs’ Class D League team.34 It was announced that Himsl would remain head coach for two weeks.

The 1961 Cubs were not a bad lot of players. In fact, the opening day lineup featured three future Hall of Fame players in Richie Ashburn (although he was nearing the end of his career), Ernie Banks, and Billy Williams. That year was Banks’ ninth season with the Cubs. At 30 years old, he was the heart of the team, coming off of four consecutive seasons with 40 or more homeruns and 100 or more runs batted in.

The 1961 season was Billy Williams’ first full season in the majors, and his performance would win him the National League Rookie of the Year award. Also in the starting lineup was Ron Santo, who many argue is deserving of Hall of Fame status. Santo was beginning his second year with the Cubs, and was considered a very promising player. Other prominent players on the team included George Altman, Frank Thomas, and Don Zimmer. However, the Cubs’ pitching corps was weak, and this would be a primary reason for the failings of the team.

The Cubs started the season on April 11 with a 7-1 loss to the Cincinnati Reds. Reds starter Jimmy O’Toole tossed a complete-game four-hitter while Reds’ sluggers Frank Robinson and Wally Post hit home runs.35 Following this first game of the season, Wrigley seemed pleased with the initial implementation of the system. Still, he claimed that he did not foresee any immediate returns from the program, stating, “This is a long-range plan” and that “it may take several years to bear fruits.” He went on to state, “The plan was designed primarily to help our lower-classification clubs and speed our farm products to the Cubs.”36

Vedie Himsl served as head coach for the initial 11games of the season, leading the team to a 5-6 record.Although it was predetermined that Himsl would be replaced as head coach and rotate to a role in the minor leagues following the games of April 23, his final two games in this rotation were portentous. The Cubs would surrender a doubleheader sweep to the Phillies by scores of 1-0 and 6-0. In the second game, Phillies pitcher Art Mahaffey struck out 17 Cubs, setting the Phillies’ club record for strikeouts in a game.37

Wrigley’s initial plan for rotation of the coaches was to remove the head coach while he was winning so as to “quit while he was ahead.” Wrigley believed that “this is a common approach, everywhere but in baseball.”38 Unfortunately for the Cubs, this would be difficult to achieve given their performance.

Following his rotation as manager, Himsl departed for San Antonio, where he would serve as a pitching instructor for the Cubs’ AA affiliate. Taking his place as head coach was Harry Craft. The other coaches in the system would remain in their initial roles. As it was with Himsl, it was announced that Craft would also serve as head coach for two weeks.

Harry Craft had managed the Kansas City Athletics from 1957 through 1959. He had joined the Cubs in 1960 as a coach. In taking the head coaching position, Craft announced that he would implement several changes, including rearranging the batting order by moving Ernie Banks from the fifth spot to the third and benching rookie Billy Williams.39 The Cubs won their first game under Craft on a 10th-inning home run by Don Zimmer, defeating the Cincinnati Reds.40 Craft would remain head coach until May 10, leading the Cubs to a record of 4-8, including losses in the final six games while under his leadership. Craft then rotated to the position of head coach of the AA San Antonio team, replacing Rip Collins, who rotated up to the big league team.

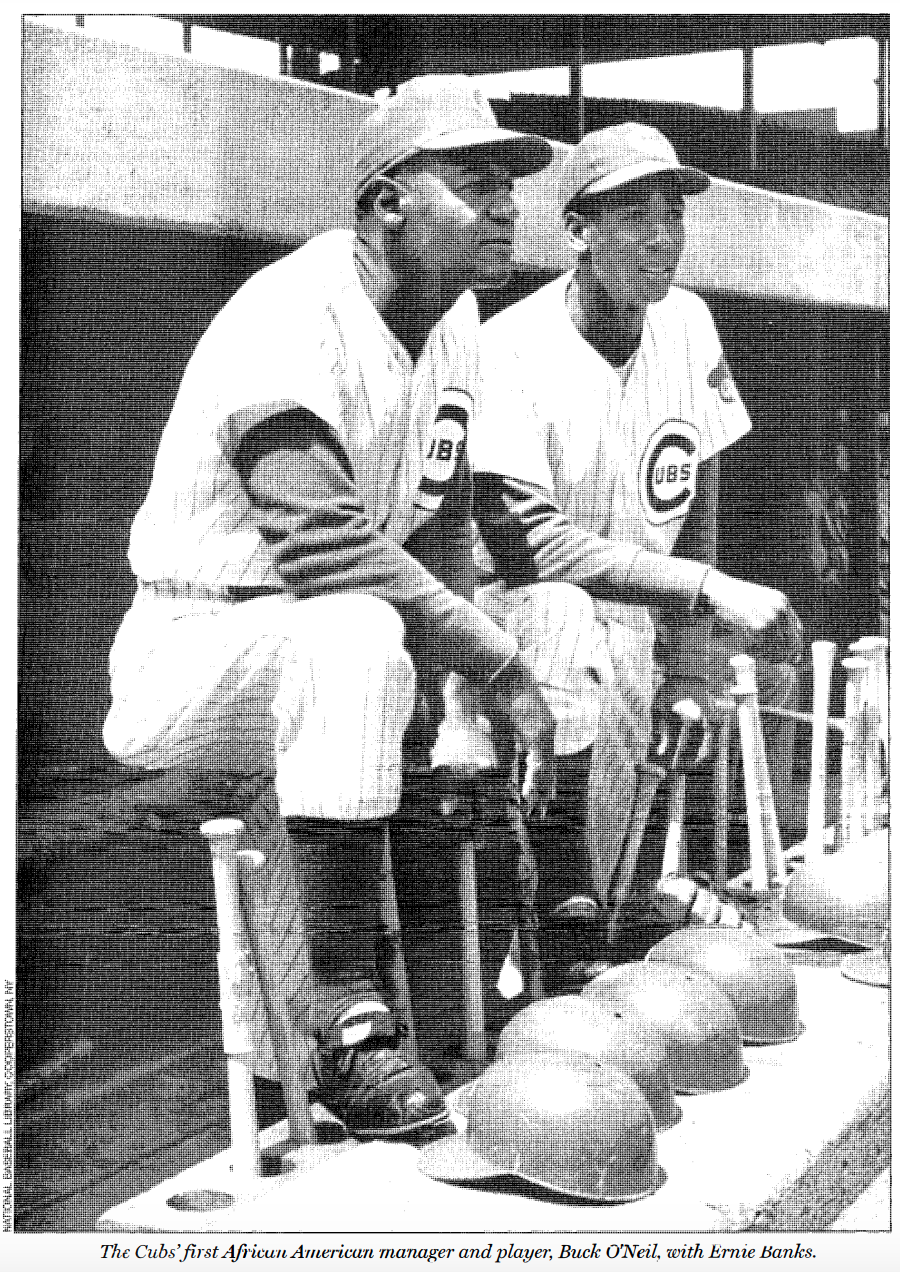

The Cubs’ first African American manager and player, Buck O’Neil, with Ernie Banks. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

In a surprising move, Vedie Himsl was reappointed as head coach following Craft’s rotation to the farm system. It was reported that because of his success in his first rotation and his relationship with the players, the two other holdover Cubs coaches, El Tappe and Bobby Adams, had recommended that Himsl regain the head coaching position.41

In personally making the announcement that Himsl would return as head coach, Wrigley stressed that “comparative records had nothing at all to do with Himsl’s return,” but he failed to indicate if there was any predefined limit to Himsl’s time as head coach.42 This move was seen by some as a possible end to the rotating-coach plan, as it had initially called for all of the coaches to take their turn as head coach. It was also speculated that the coaches were not making any recommendations, and that Wrigley and vice-president John Holland had decided that Himsl was in fact a good manager and not in need of replacement.43 Such speculation on the decision-making processes within the Cubs organization would be the norm for the season.

The team’s performance under Himsl’s second rotation as head coach would not be nearly as successful as its relatively mediocre record under his first go-round. They hegan by losing on May 12 to Sandy Koufax and the Los Angeles Dodgers and would go on to but five wins against 12 losses in his rotation, which lasted until May 30.

Some of the deficiencies in team management caused by the rotating coaches system were evidenced in the early season handling of Ernie Banks and Billy Williams. Many of these manipulations were plainly due to the lack of consistency and long-term responsibility in team management by the coaches.

Banks was of course regarded as the premier player on the Cubs, but was having a difficult season in 1961. He had aggravated an old knee injury during spring training, and was slowed considerably in the early season. Banks began the season at shortstop, the position he had held down for the previous seven seasons, but played poorly. On May 23, despite considerable pressure from the press to have him move to first base, Banks was shifted to left field, a position he had never played. Still hobbled by the bad knee, Banks had little range or agility in the outfield and likewise did not have the arm strength necessary to throw out runners.

On June 16, Banks was moved to first base, another new position. The Cubs had considerable difficulty filling the first base position in 1961, using a total of eight men at the position.44 Although he did not require much range at first, he was still no better than adequate. After only seven games at first and a brief time on the bench, Banks was moved back to shortstop.45 Despite all of these moves, Banks was still a threat at the plate, hitting two home runs in a game on four different occasions during the season.

Billy Williams, on the other hand, had a fabulous spring training, and was perched to become a star with the Cubs. However, he was also was shifted about considerably in the early season. Despite the fact that he had played primarily as a left fielder in the minors, he began the 1961 season in right field. After 18 games in right, Billy was moved to left field, albeit temporarily. He was shifted between left and right, and was benched for a time, until June 16, when it was passed down from the office of John Holland that Billy was to start and be stationed permanently in left field.46

Upon his permanent installation in left, Williams went on a tear, hitting a grand slam in his first game and then going on to collect 10 hits in 19 at-bats in the subsequent few games. It was here that he was most comfortable, and went on to field and hit at the level worthy of a Rookie of the Year.

Following Himsl’s second rotation, the Cubs would experiment with rotating coaches on an extremely short-term basis. Three separate men would serve as head coach over the course of the next nine days. First up was Elvin Tappe, who was named head coach prior to the game on May 30. Tappe, only 32 years old, had also served as a coach for the previous three seasons. Wrigley stated that he was reluctant to appoint Tappe as head coach until he had some experience. Tappe, however, took full advantage of the opportunity, leading the Cubs to wins over the Phillies in both the games he served as head coach.

Tappe then handed the reins back to Harry Craft. Craft was head coach for three days, from June 2 to June 4, and led the Cubs to three wins and a loss to the Reds. Vedie Himsl was then renamed head coach on June 5. He could not maintain the luck of his two predecessors, as the Cubs were 0-3-1 against the Cardinals in the games he served as head coach.

At this point in the season the Cubs were in seventh place in the National League, ahead of only the lowly Phillies, and their record stood at 19 wins and 30 losses. Rip Collins was scheduled to next assume the role of head coach but begged out of the position, preferring instead to work as a coach with the younger players. So, on June 9 El Tappe was once again named head coach.47

Four days later, it was announced that the Cubs’ head-coaching merry-go-round would come to a halt, and that Tappe would remain head coach for the foreseeable future. However, it was also stated that the organization was definitely not giving up on the rotation plan and that it could begin again at any time.48 Tappe would remain head coach for the next 79 games. During this time the Cubs would continue to rotate their coaches, other than Tappe, throughout the organization. During the 1961 season their AAA team at Houston, AA team at San Antonio, and Class B team at Wenatchee, Washington, all had four men serve as head coaches, including either Harry Craft or Vedie Himsl, who of course also managed the major league team.

El Tappe remained head coach until September 1, when he surrendered the duties to Lou Klein. Tappe was now assigned to begin a trip through the Cubs’ farm system and scout the talent. Klein was yet another member of the management team who did not have any major league managerial experience prior to 1961, although he had played in the majors, and was most renowned for being one of the players who had jumped to the Mexican League in the 1940s.49 Klein had started the season in Carlsbad, coaching the Cubs’ Class D team in the Sophomore League-quite a change from the big leagues. From Carlsbad, Klein then went to coach at Houston for a time, and had been with the Cubs since July 18.

Klein would direct the team for 11 games in nine days, with the Cubs tallying a record of 5-6 while under his direction. On September 12, he turned over head coaching responsibilities to El Tappe, who now entered into his third rotation as head coach. Tappe directed the team for the remainder of the season, during which time the Cubs won only five games while losing 11.

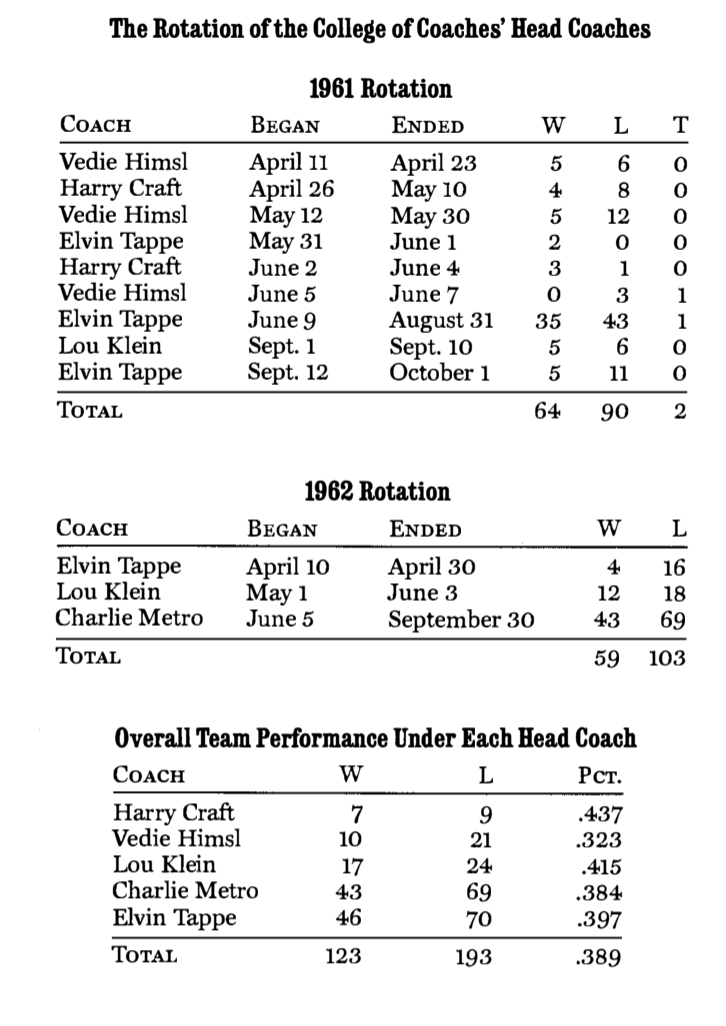

Overall, the Cubs would finish the 1961 season in seventh place (ahead of the Phillies), with a record of 64 wins and 90 losses. On the bright side, they did improve upon their 1960 record by four games, and were the only team in the National League to finish with a winning record against the pennant-winning Cincinnati Reds. In looking at the final National League statistics, clearly the pitching and defense were the weak links. They led the league in both errors and runs allowed.50

Despite his many ailments, Ernie Banks still slugged 29 home runs. Ron Santo had a very good sophomore season, hitting 23 home runs and establishing himself as an excellent.third baseman. Billy Williams hit 25 home runs and had 86 runs batted in, earning him the National League Rookie of the Year award. Still, the Cubs had a long way to go to become a pennant contender. Immediately following the season, Wrigley stated that the Cubs would “definitely use the same coaching system next year although there will certainly be some changes in the personnel of the panel.”51

Reaction of the Players to the First Year

Although there were no complaints printed in the media from the players during the 1961 season, it is apparent that there was some dissension. When it was suggested to Wrigley that the lack of a single authority affected team discipline, Wrigley admitted, “There were older veterans who did not think much of the coaching system,” but “they were fined and brought into line.”52

The first published criticism from the players, albeit not very strong, came from pitchers Moe Drabowsky and Seth Morehead after they were traded to the Milwaukee Braves just before the start of the regular season. They said that “the system is okay for spring training,” but they doubted its merits during the regular season.53

The most vocal critic of the coaching system was Cub infielder and team captain Don Zimmer. He ripped into the coaching system in a newspaper article following the 1961 season. He was quoted as saying that it was only natural that the nine coaches would have nine different approaches to baseball He called the college of coaches idea “a joke and that it was doomed to failure the moment it was created.” He explained that he felt the coaches all preferred various players and “treated the players as chessmen, not thinking breathing players.”54 Zimmer did not return to the Cubs after the 1961 season, as he was exposed to the expansion draft and selected by the New York Mets.55

The Second Year of the College of Coaches

Prior to the 1962 season, Wrigley continued to reiterate that he intended to keep the rotating-coach system in place. Showing his devotion to the system, he expressed that he believed that the rotating-coach system was working and that the Cubs should have finished in the first division in 1961. However, Wrigley did indicate that in 1962 there would be less shifting around of coaches.56

The Cubs started the 1962 season in much the same way they started 1961, with four coaches at the major league level and six additional coaches dispersed throughout the farm system. Taking the place of Harry Craft, who left the Cubs when he was named manager of the expansion Houston Colt .45’s, was Charlie Metro. He had never managed on the major-league level, but had managed the previous five seasons at AAA, most recently with the Denver Bears of the American Association, a farm team of the Detroit Tigers. He had been quite successful in those five seasons, leading each team to a top three finish in their league.

In looking at the five primary candidates to serve in the head coaching job in 1962, it is clear that the Cubs were experimenting with various approaches to player management. El Tappe, Rube Walker, and Bobby Adams were known as laid-back leaders with a teaching approach, while Lou Klein and Charlie Metro were more authoritarian and known as disciplinarians. In describing his managerial approach, Metro said, “I’ll never win any popularity contests.”57 Just as teams are often inclined to hire a disciplinarian after the tenure of a soft-stanced manager, the Cubs could rotate men with these disparate management styles without the bother of hiring and firing.

The 1962 Cubs were quite similar to the team fielded in 1961. To start the season, Banks was shifted to first base, but,was now more experienced and comfortable at the position. Santo, Williams, and Altman held down their respective positions of third base, left field, and right field respectively. After excellent minor league performances the previous season, rookie Ken Hubbs was given second base and rookie Lou Brock was stationed in center field. Offensively, the team looked strong. Pitching, however, continued to be a problem. The rotation of Bob Buhl, Don Cardwell, Dick Ellsworth, and Glen Hobbie held little more promise than the previous season’s staff. Charlie Metro described the team and its mediocre pitching as “a car missing a wheel.”58

The 1962 Cubs coaches did shift around far less than in 1961. On the farm level, all of the clubs, save for the D-level club at Palatka of the Florida State League, had only one head coach for the entire season.59 Coaches were still rotated about the minor league clubs, but served as instructors instead of in a lead role. Likewise, there was considerably less shifting of the coaches on the major league level, as only three men served as head coach.

El Tappe, who had served three rotations as head coach the previous year, started the season in the lead role. The team got off to a rocky start, losing nine of their first 10 and winning only four of the 20 games played under Tappe. Lou Klein then was assigned as head coach on May 1. The team’s performance would improve under Klein, but not to the point of anything resembling success. Klein was replaced on June 3, after leading the team to 12 wins and 18 losses.

The final head coach for 1962 was Charlie Metro. It was thought inevitable by many that Metro be given ample opportunity to replicate his minor league managerial success with the Cubs. After a month as head coach, Metro approached Wrigley to discuss his rotation to the minor leagues. When asked by Wrigley if he would rotate, Metro said he would go, ”but he sure as hell won’t like it.”60

It was decided to keep Metro on as head coach, effectively ending the rotation of head coaches on the big league team. He would go on to lead the Cubs for the final 112 games of the season. The Cubs still played poorly, winning only 43 games while losing 69. At season’s end, the Cubs finished with a record of 59 wins and 103 losses. They ended up in ninth place, ahead of only the legendarily bad New York Mets, playing in their inaugural season. To their embarrassment, the Cubs finished behind the other new expansion team in the National League, the Houston Colt .45’s. On a historic basis, the Cubs’ .364 winning percentage in 1962 represented the worst performance in the 87-year history of the club.

In 1962, the college of coaches approach was far more contentious both on the player and the management levels than in 1961. This was especially true during Charlie Metro’s tenure. Metro banned golf clubs from the clubhouse after learning that some of the players were playing on the morning of day games.61 He later criticized several unnamed players and coaches through the press for being “happy losers.” This caused clear dissension in the coaching ranks. Metro tried to ban shaving in the clubhouse, but was outvoted by his fellow coaches. He also established a daily 10:00 A.M. coaches meeting, which was poorly received by the other coaches, who had been meeting at night after games. It reached the press that both El Tappe and Lou Klein were very critical of Metro and his approach to team management.62 At the time, the Cubs had a record of nine wins and nine losses under Metro.

Despite the discord among the coaches, Metro received an endorsement from Wrigley, who made it clear that Metro would likely remain as head coach for the entire season.63 In a later show of support for Metro, all of the other Cubs coaches, except for Metro, were at some point rotated to positions within the farm system.64 It is interesting that Wrigley, who claimed his disdain for the use of the term “manager” due to an association with the word “dictator,” saw fit to support some of the more disciplinarian efforts of Metro.

Wrigley continued to support Metro, however, following the season Metro was fired. He was the only coach from the 1962 season to be relieved of his position. In retrospect, Metro was glad for the opportunity to serve as head coach with the Cubs. However, he came to believe that the college of coaches approach “would never work” most especially due to the rotation of pitching coaches, a position he believed that required stability.65 Despite all of this turbulence, Wrigley remained unmoved in his belief in the college of coaches system, and announced at season’s end that it would continue on.66

Although the players held their tongues and did not publicly criticize the coaching methods at the time, almost all of the players did disparage it years later. Lou Brock stated, “Fourteen chiefs is an awful lot of brass for just 25 Indians, only eight of whom play every day anyhow. The system was not good for morale, and there was plenty of tendency toward insubordination on the team. The trouble was, how could you know who to insubordinate to?”67

Pitcher Dick Ellsworth, who finished with a record of 9 wins and 20 losses in 1962, believed that the college of coaches offered “no leadership” and that “the lack of leadership was reflected in how we did on the field.”68 Catcher Dick Bertell remembered the system as “horrible,” recalling, “We would go from a manager who would like to bunt and hit-and-run one week to a guy who didn’t do any of that the next week.” Bertell also thought that “the problem with the Cubs was Phil Wrigley.”69 At the end of the 1962 season, pitcher Don Cardwell went to John Holland and told him that he did not like the system. A week later, he was traded. 70

Buck O’Neil’s Experiences in the College of Coaches

One positive outcome of the college of coaches experiment was the hiring of the first African American coach in the major leagues. John “Buck” O’Neil, who had served the Cubs for seven seasons as a scout and spring training instructor, was named a coach on May 29, 1962.71 O’Neil had played for and/or managed the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues for 17 years. He had distinguished himself as a manager with the Monarchs, and was selected to manage the East-West All-Star game four times. He was responsible for the signing of Ernie Banks and George Altman, who had played under him when he managed the Monarchs. He also signed Lou Brock and was instrumental in the development of Billy Williams. Despite these achievements for the Cubs, O’Neil believes that if it were not for the college of coaches and the additional opportunities it offered, he would not have been named as a coach.72

In an interview soon after he was hired as a coach, O’Neil called the college of coaches a “wonderful innovation.”73 Years later, however, O’Neil admitted that he “did not think much of the idea of the college” but he was not going to turn down the opportunity to work as a coach on the major league level.74

When O’Neil was hired, it was announced that he would be an instructor with the Cubs, although he would not be a part of the rotating coaches system. Thus he would not have the opportunity to serve as head coach. Later, Cubs vice-president John Holland did state that it was possible that O’Neil might join the rotation and serve as head coach one day, perhaps as soon as the following season.75

However, it would soon become apparent to O’Neil that this would be unlikely. During one game against the Houston Colt .45’s, Cubs head coach Charlie Metro was thrown out of the game. Soon after, his replacement, El Tappe, who had been coaching third base, was also thrown out. Several of the players on the Cub bench, including Ernie Banks, realized that O’Neil should take over as third base coach. This was not to be however, as Fred Martin, the Cubs pitching coach, trotted all the way in from the bullpen to take over third base coaching responsibilities.

O’Neil would later find out that Charlie Grimm had previously made it clear to the other coaches that O’Neil was not to coach on the base paths. Grimm apparently told Metro that O’Neil would take over someone’s job is he was given the opportunity. Although it was never stated, it is difficult not to assume that O’Neil was kept off the field because of his race. He would never get the chance to serve as a first or third base coach, which he would later describe as one of his few disappointments in baseball.76

Generally, O’Neil’s experiences as the first African-American coach and member of the the college of coaches were positive. He believed that he “didn’t face what Jackie did” with regard to his treatment. O’Neil stated that although he demanded the respect of the players and his peer coaches on the team, he did not face any problems and was on a friendly basis with almost everyone.77

Following the 1962 season and the firing of head coach Charlie Metro, Doc Young of the Chicago Defender promoted the idea that O’Neil be named the next manager of the Cubs.78 But this was not to be.79 Although O’Neil would certainly have liked to manage the team, he returned to scouting and special assignments for the Cubs in 1964, and would eventually sign Oscar Gamble, Lee Smith, and Joe Carter to the Cubs. It would be 13 more years after O’Neil integrated the coaching ranks until Frank Robinson was named the first African American manager in major league baseball, with the Cleveland Indians in 1975.

The End of the Experiment

At his annual January press conference in 1963, Wrigley finally gave up on the college of coached approach. He admitted that the system had failed, stating, “despite our grand plans, each of the head coaches had his own individual ideas,” and “the aim of standardization of play was not achieved because of the various personalities.” He added, “the players did not know where to turn,” and “the goal was not attained.”80

In announcing the end of the college of coaches, however, Wrigley was not ready to return the Cubs to a conventional management system. At the press conference, Wrigley introduced the Cubs’ newly appointed “athletic director,” Robert W. Whitlow. Whitlow, who was 43 years old, was a retired colonel in the United States Air Force. He was a highly decorated World War II fighter pilot.81 His most recent position was as the first athletic director of the United States Air Force Academy. Neither the Cubs nor any other major league team had an athletic director, a position associated with college sports. However, the title of athletic director was a misnomer as it related to the responsibility granted to Whitlow. He was expected to head up the entire organization and answer only to Wrigley.

Whitlow, Wrigley announced was the “type of man we had hoped to get from among the many coaches brought into the organization the past few years.” Whitlow himself announced that his job was to be a centralized director responsible for the playing end of the game.” He also announced that he might sit on the bench in uniform during games.82 Wrigley did state that there would still be no position with the title manager and that the Cubs would still be led by a head coach. He added that the head coach and all of the other coaches would report directly to Whitlow.

On February 20, Bob Kennedy was named as the new head coach for the Cubs. It was also announced that the 43-year-old Kennedy was expected to remain as head coach for the entirety of the season. Kennedy had served as the general and field manager for the Cubs’ AAA club in Salt Lake City the previous year. Kennedy’s coaching staff consisted of Lou Klein, Fred Martin, and Rube Walker. El Tappe was assigned as manager at the AAA level, and the other six members of the college of coaches were dispersed throughout the Cubs’ farm system.83

1963 and 1964 to Durocher

The Cubs responded to the new stability in the coaching ranks and finished the 1963 season with a record of 82-80, their first winning record in 17 years. Tragedy struck the Cubs in February 1964, when their second baseman Ken Hubbs was killed in a plane crash. In 1964, the team slipped a bit, finishing with a record of 76 wins and 86 losses. Bob Kennedy and the rest of the Cubs coaches remained intact. The year 1965 however, saw team performance slide further. After 56 games, Kennedy was replaced by Lou Klein. The team finished in eight place with a record of 72-90.

Wrigley’s experiment with Whitlow as athletic director was nearly as disastrous as the college of coaches. On one hand, Whitlow was rather forward thinking in his approach. He proposed to study and implement systems of conditioning and “applied psychology.” He had a fence erected in center field in Wrigley Field, dubbed “Whitlow’s Wall,” to serve as a better hitter’s background.84 He also championed Lou Brock as a future star with the Cubs.

However, his influence within the Cub organization slowly dwindled. He lost a power struggle with head coach Bob Kennedy toward the end of the 1963 season, when Kennedy essentially told Whitlow to keep away from the players.85 He developed exercise regimens and purchased special exercise equipment and designed special diets, including powered nutritional supplements, for the players. All of these schemes were soundly avoided and rejected by the players. Finally, following the 1964 season, Whitlow resigned from the Cubs, stating that he “wasn’t earning his salary.” In commenting on Whitlow’s lack of success, Wrigley suggested that Whitlow “was too far ahead of his time” and that ”baseball people are slow to accept anyone with new ideas.”86

A final disaster which is often attributed to the college of coaches was the trade which sent Lou Brock to the St. Louis Cardinals. On June 15, 1964, the Cubs traded Lou Brock, along with pitchers Jack Spring and Paul Toth, for Cardinal pitchers Ernie Broglio and Bobby Shantz and outfielder Doug Clemens. At the time the Cubs had a .500 record and were 1 1⁄2 games ahead of the Cardinals in the standings.

The Cubs, hoping to build on their success in 1963, were seeking more pitching in Broglio, who had won 18 games the previous season, and the veteran reliever Shantz. The trade was well received in Chicago, where the press was happy to be rid of what they perceived as an underachieving Brock.87

Following the trade, the fortunes of the two teams reversed, with the Cardinals winning the National League pennant and the World Series, and the Cubs finishing in eighth place. Likewise, Brock went on to a Hall of Fame career, collecting 3,023 hits and stealing a then-major league record 938 bases. Broglio hurt his shoulder after joining the Cubs and lost his effectiveness. Although it is clear that Brock suffered in the early part of his career under the college of coaches, he did play more than a full season for the Cubs under a stable management arrangement. The Cubs had simply failed to recognize Brock’s potential and gave up on him too soon.

The true end of the college of coaches came on October 25, 1965, with the hiring of Leo Durocher as Cubs manager. In announcing his hiring, a representative of the Cubs stated that the title of the team leader did not matter as long as he had the ability to take charge. Responding to this statement, Durocher, in no uncertain terms, expressed his opinion. He stated, ”I’m not the head coach here. I am the manager.”88

Durocher, after a terrible 1966 season, did lead the Cubs to contention in 1967, 1968, and famously in 1969, when the Cubs lost a substantial lead and subsequently the National League East division title to the New York Mets. It has been suggested that the success of Durocher’s Cub teams, and the 1969 team in particular, was due at least in part to the development of such players as Don Kessinger and Glenn Beckert by the rotating-coach system. El Tappe, for one, has stated, “The 1969 team was a team the coaching plan developed.”89 However, this likely overstates the influence of the college of coaches as the vast majority of impact players on that team were with the Cubs before or came to the Cubs after the system was used.

Conclusions

Clearly, the college of coaches, as it was employed, was a fiasco. The system was difficult for both the coaches and the players. The coaches were expected to be familiar and work with not just one but three or four teams over the course of a season. This must have been overwhelming. Likewise, the players were given conflicting orders and advice, and were expected to perform equally under various leadership personalities. Arthur Daley’s quote, that the Cubs would be “the most coached and least managed team in baseball.” was certainly true.

There were several positive outcomes as a result of the innovative thinking that was behind the college of coaches concept. The more unified approach to player development through the use of roving instructors, consistent teaching, and coaching methods, and a general organizational approach to player development did become the norm in baseball. The use of computer technology, albeit at a very basic level, was certainly prescient. Likewise, the hiring of Buck O’Neil and an interest in the integration of coaches was also, relative to the rest of major league baseball, ahead of its time. In all, the college of coaches experiment was an innovative, tumultuous, frustrating, and, in the end, disappointing time in the history of the Chicago Cubs.

RICHARD J. PUERZER is an associate professor of Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management at Hofstra University and a member of SABR’s Elysian Fields Chapter. This paper was presented first at the Seventeenth Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 2005.

Notes

1. Edward Prell. “No Manager for Cubs in ’61-Wrigley,:’ Chicago Daily Tribune, January 13, 1961, CI.

2. John C. Skipper. Take Me Out to the Cubs Game: 35 Former Ballplayers Speak of Losing at Wrigley. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2000, 219.

3. Paul M. Angle, Philip K. Wrigley: A Memoir of a Modest Man, New York: Rand McNally, 1975, 42-44.

4. Angle, 69-76.

5. For an in-depth description of Griffith’s work with the Cubs, see: Christoper Green. “Psychology Strikes Out: Coleman Griffith and the Chicago Cubs:’ History of Psychology, vol. 6, no. 3 (2003): 267-283.

6. Angle, 59.

7, Skipper, Take Me Out to the Cubs Game, 220.

8. Jonathan Fraser Light. The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1997, 129.

9- Derek Gentile. The Complete Chicago Cubs. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal, 2002. The Cubs did finish at .500, with a record of 77-77 in 1952, good enough for fifth place in the National League.

10. James Enright, “P.K. Defies Critics of ‘Coaching College’:’ The Sporting News, January 25, 1961, 3.

11. John C. Skipper. Inside Pitch: Classic Baseball Moments. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1996, 42-43.

12. Skipper, Inside Pitch, 44.

13. “Confused Cubs Will Start Without Manager:’ The Washington Post, January 13, 1961, A23.

14. “Managers? They Aren’t Important:’ Los Angeles Times, January 14, 1961,A2.

15. Prell. “No Manager for Cubs in ’61-WrigleY:’ CI.

16. Jerome Holtzman. “Cubs Concoct ‘Coach of Month’ Plan to Speed Title Time-Table:’ The Sporting News, January 18, 1961, 9 and 12.

17. Jerome Holtzman. “Inside Story: The Cubs’ Curious Experiment:’ Sport, Vol 32 No 2, August 1961, 79.

18. Frank Gianelli. “P. K. Junks ‘Minor Leaguer’ Tag for Kids.” The Sporting News, March 8, 1961, 3.

19. Prell, “No Manager for Cubs in ’61 – Wrigley;’ CI.

20. Alan Schwarz. The Numbers Game: Baseball’s Lifelong Fascination with Statistics. New York: Thomas Dunne, 2004, 136. Although Schwarz writes that the Cubs did not use computers until about 1963.

21. “Confused Cubs Will Start Without Manager.” The Washington Post, January 13, 1961, A23.

22. John P. Charmichael. “Cub Minority Stockholder Gives Views on P. K:s Plan:’ The Sporting News, January 25, 1961, 3.

23. Al Wolf. “Cub Pilot Plan Poses Problem:’ Los Angeles Times, February 15, 1961, C2.

24. “‘Cubs Exception to Pattern of Automation; JFK Says:’ The Sporting News, April 20, 1963, 5.

25. “P. K:s Coach Stint May Fool ‘Em:’ The Sporting News, January 18, 1961, 9.

26. “Wrigley’s Reasoning:’ Chicago Daily Tribune, March 22, 1961, 12.

27. Edward Prell. “Wrigley Blasts ‘Obsolete Baseball Policies’:’ Chicago Daily Tribune, March 17, 1961, CI.

28. Arthur Daley. “The Revolving-Door System:’ New York Times, February 1, 1961, 44.

29. “Richie ‘Confused’ by Wrigley Plan.” The Sporting News, January 25, 1961, 10.

30. Jim Brosnan. Pennant Race. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1962, 77 78.

31. Jerry Holtzman. “Drott and Drabowsky Start Comeback Bids:’ The Sporting News, March 8, 1961, 3.

32. “Wrigley Details Cubs’ Philosophy:’ The Washington Post, March 18, 1961,Al3.

33. Prell. “Wrigley Blasts ‘Obsolete Baseball Policies’:’ CI.

34. Angle, 132.

35. Edward Prell. “Reds Rout Cubs, 7-l; Braves Lose, 2-1:’ Chicago Daily Tribune, April 12, 1961, CI.

36. Jerry Holtzman. “Five-Man Board Acts as Bruin Brain Trust.” The Sporting News, April 19, 1961, 21.

37. “Mahaffey Strikes Out 17 Cubs as Phillies Sweep Double-Header:’ New York Times, April 24, 1961, 40 .

38. Frank Gianelli. “P. K. to Shelve Head Coach Before Loss Streak Mounts:’ The Sporting News, March 8, 1961, 3.

39. Edward Prell. “Baseball Spotlight on Chicago:’ Chicago Daily Tribune, April 25, 1961, BL

40. “Cubs Beat Cincy on Zimmer’s Homer in 10th:’ The Washington Post, April 27, 1961, D9.

41. Edward Prell. “Hims! Supplants Craft At Cubs’ Helm:• Chicago Daily Tribune, May 12, 1961, CI.

42. James Enright. “Switch Back by Wrigley in Coach Board:’ The Sporting News, May 17, 1961, I.

43. Edward Prell. “Hims! Recall Indicates End of Cubs’ Multiple Coach Plan:• Chicago Daily Tribune, May 13, 1961, CI.

44. This information and much of the other statistical information was drawn from www.retrosheet.org.

45. Bill Libby. Ernie Banks: Mr. Cub. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1971, 83-85.

46. Billy Williams and Irv Haag. Billy: The Classic Hitter. New York: Rand McNally, 1974, 75-76.

47. “Rip Collins Ducks Tum as Field Boss of Cubs:• The Washington Post, June 9, 1961, C5.

48. “Cubs Shelve Rotating Head Coach System:’ The Washington Post, June 14, 1961, C2.

49. “Lou Klein Named Cubs’ Head Coach:’ The Washington Post, September 1, 1961, DI.

50. Statistics were taken from Official Baseball Guide-1962, Compiled by J. G. Taylor Spink, Paul A. Rickart, and Clifford Kachline. St. Louis, MO: Charles, C. Spink & Son, 1963.

51. Edgar Munzel. “P. K. to Shake Up Cubs’ Board of Tutors, Continue Plan in ’62:’ The Sporting News, October 11, 1961, 20.

52. Munzel. “P. K. to Shake Up Cubs’ Board of Tutors:’ 20.

53. Jerome Holtzman. “Inside Story: The Cubs’ Curious Experiment,” Sport, Vol 32 No 2, August 1961, 78.

54. Edgar Munzel. “Zimmer Rips Cub Coaching Setup as Flop;’ The Sporting News, October 25, 1961, 22.

55. Don Zimmer with Bill Madden. Zim: A Life in Baseball. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001, 53.

56. Edward Prell. “Owner of Cubs Sees the Light! May Illuminate Wrigley Field.” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 12, 1962, CI.

57. Richard Dozer. “Hurling Aids Out of Consideration.” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 28, 1962, CI.

58. Charlie Metro with Tom Altherr. Safe By a Mile. Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press, 2002, 250.

59. Official Baseball Guide-1963, Compiled by J. G. Taylor Spink, Paul A. Rickart, and Clifford Kachline. St. Louis, MO: Charles, C. Spink & Son, 1964.

60. Metro with Altherr, 251.

61. Metro with Altherr, 252.

62. Richard Dozer. “Showdown Near Among Staff of North Siders.” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 23, 1962, CI.

63. David Condon. “Wrigley Indorses Metro as No. 1 Man!” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 23, 1962, CL

64. “Latest Cub Shift Moves 4 Coaches.” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 23, 1962, D3.

65. Charlie Metro, phone interview with Richard J. Puerzer, March 2, 2006.

66. Richard Dozer. “Cubs Fire Metro; Coach Plan Stays:’ Chicago Daily Tribune, November 9, 1962, Cl.

67. Lou Brock and Franz Schulze. Stealing Is My Game. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1976, 53.

68. Skipper, Take Me Out to the Cubs Game, 103.

69. Skipper, Take Me Out to the Cubs Game, 118-119.

70. Skipper, Take Me Out to the Cubs Game, 125.

71. “Cubs Sign Buck O’Neil As First Negro Coach:’ New York Times, May 30, 1962, 12.

72. Sean D. Wheelock. Buck O’Neil: A Baseball Legend. Mattituck, NY: Amereon House, 1994, 82-83.

73. “First Negro Coach In Majors:’ Ebony, Vol. 17 No. 10, August 1962, 29-31.

74. John “Buck” O’Neil, phone interview with Richard J. Puerzer, February 3, 2005.

75. ”Vice Prexy Says O’Neil May Head Cubs Eventually:’ Ebony, Vol. 17 No. 10, August 1962, 32-33.

76. O’Neil interview. A similar account of this situation is found in: Buck O’Neil with Steve Wulf and David Conrad. I Was Right on Time. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996, 213-214.

77- O’Neil interview.

78. A. S. “Doc” Young. ”An Open Letter to Cub Owner Phil Wrigley:’ The Chicago Defender, March 30, 1963, 20.

79. O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrad, 215.

80. Edward Prell. “Col. Whitlow Tukes Over-Cubs Appoint Athletic Director:’ Chicago Daily Tribune, January 11, 1963, CL

81. Jerome Holtzman. ”Whitlow Attacks Cub Defeat Pattern:’ The Sporting News, April 20, 1963, 5.

82. Prell. “Col. Whitlow Takes Over-Cubs Appoint Athletic Director;’ Cl.

83. Edward Prell. “Cub Coaching Staff Stops Revolving!” Chicago Tribune, February 21, 1963, DI.

84. C. C. Johnson Spink. “Cub Colonel Loses Rank to Kennedy:’ The Sporting News,September 7, 1963, 7.

85. Spink, “Cub Colonel Loses Rank to Kennedy,” 7.

86. Jerome Holtzman. ”Whitlow Takes Walk-‘Game Not Ready for Him’:’ The Sporting News, January 23, 1965, n.p.

87. Brock and Schulze, 61.

88. Light, 174.

89. Skipper, Take Me Out to the Cubs Game, 116.