Jackie Robinson, Republican

This article was written by Jeff English

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

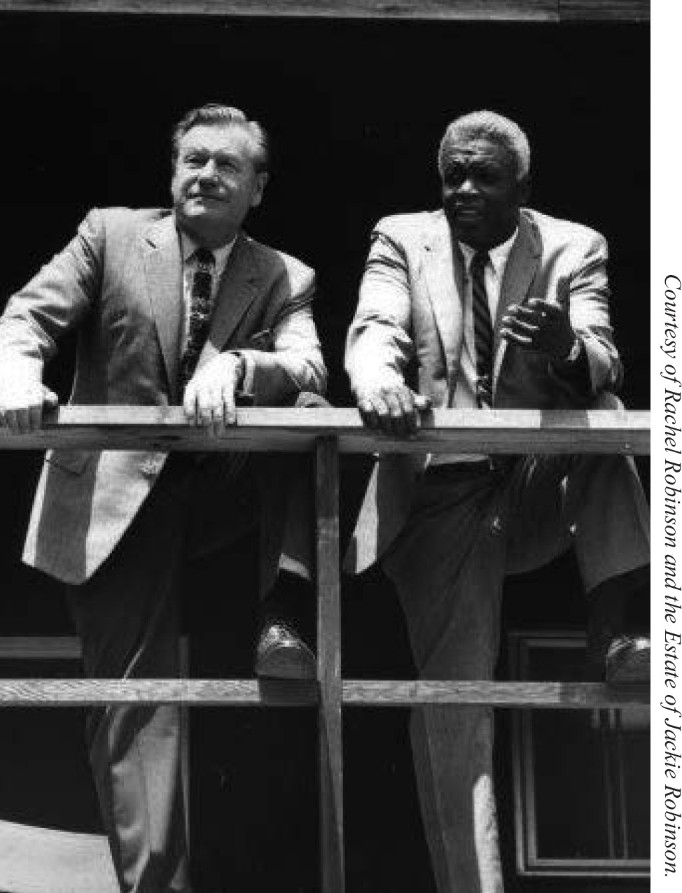

Nelson Rockefeller stands with Jackie Robinson, who served as a special assistant on community affairs for the New York Governor in the 1960s.

Between 1960 and 1968, Jackie Robinson was widely regarded as the most famous Black Republican in the country. Following his announced retirement from baseball in January 1957, and in remarkably short fashion, he dived head-first into the world of corporate America and the civil-rights movement, with equal gusto. He spent the next three years polishing old skills and developing new ones while demonstrating a knack for fundraising on behalf of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Splitting his time as a vice president at the Chock Full o’ Nuts restaurant chain in New York, and as an active member of the NAACP, he maintained a relentless travel schedule that carried him from one side of the country to the other. By the time he began hosting a radio show and publishing a nationally syndicated newspaper column in 1959, his reach had grown extensive. Thus, when the time came for the nation to turn its eyes to the 1960 race to succeed Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower as president, Robinson’s political support was deemed a valuable commodity.

Prior to his retirement from baseball, Robinson’s political involvement was minimal, occasionally taking the form of soliciting funds for socially conscious projects such as repairs for a community center.1 When he was hired in the spring of 1959 by the New York Post to write the newspaper column, editor James Wechsler described Robinson as, “an intelligent, independent, and articulate human being who follows no party line.”2 In one of his first columns for the Post, Robinson explained to his readers his approach to political participation:

I guess you’d call me an Independent, since I’ve never identified myself with one party or another in politics. As a Negro, I’ve been wooed by the Democrats with the memory of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, and cultivated by the Republicans with the memory of Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War. But, like more and more people nowadays, I always decide my vote by taking as careful a look as I can at the actual candidates and issues themselves, no matter what the party label or the ancestral ghost.3

Robinson was in fact registered as an independent dating at least as far back as his decision to buy a home in Stamford, Connecticut, in 1956.4 Although his time as an operative and influence in American politics lasted from his retirement in 1957 until his untimely death in October 1972, it was during the period from 1960 through 1968 that he exerted his greatest impact. Robinson often lent his considerable support nationwide to Republican and Democratic candidates alike, at all levels of government, who opposed Jim Crow and desired equality for all Americans. He held a sincere desire for a robust two-party system, honest and open debate, and for the success of neither party to hinge on a maintenance of the status quo. But set against the backdrop of a rapidly changing American political landscape, Robinson somehow became not only the most prominent Black Republican in America but also one of the party’s sharpest and most damning critics, often at the same time. In a 2019 assessment of what he deemed a kind of “radical legacy,” author David Naze described Robinson’s political identity as manifesting itself “in his attempt to publicly articulate his critical insights regarding the contemporary American racial landscape, a version that runs counter to the neat, obedient version to which most Americans have become accustomed.”5 In its proper context, Jackie Robinson’s political life, like so much else about the man, defies convenient labels.

Although the news was leaked beforehand, the January 22, 1957, issue of Look magazine published an exclusive Robinson-penned essay announcing his retirement from baseball. In the essay, he told readers he had accepted an offer from William Black, founder and owner of the Chock Full o’ Nuts restaurant chain in New York, to become the company’s vice president for personnel. He described his excitement over the prospect of spending more time with his family. And he offered no regrets, crediting his time in baseball for opportunities ranging from meeting Branch Rickey and breaking the game’s color line, to his 1949 testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee rebuking entertainer Paul Robeson’s purported statement that Black Americans were unwilling to fight in a war against the Soviet Union. Robinson’s position at Chock Full o’ Nuts included a March starting date, and made him the first Black US vice president of a national corporation.

On January 6, 1957, at the behest of Roy Wilkins, executive secretary of the NAACP, Robinson assumed the role of national chairman for the organization’s 1957 Freedom Fund drive with the stated goal of raising one million dollars.6 In his 1972 autobiography, I Never Had it Made, Robinson credits his new boss for encouraging his involvement, writing that Black “approved wholeheartedly of my participation, and if it didn’t interfere with my work at Chock, I was free to use company time to travel, work, and speak for the NAACP.”7 On Sunday, April 14, Robinson appeared on NBC’s Meet the Press and fielded questions about the Freedom Fund drive and baseball’s reserve clause. In response to a question concerning people claiming the NAACP was moving too fast, Robinson responded, “I think if we go back and check our record, the Negro has proven beyond a doubt that we have been more than patient in seeking our rights as American citizens.”8 On June 8, 1957, Connecticut’s Democratic Governor Abraham Ribicoff appointed Robinson to a newly created three-man board of parole as part of a broader effort to reform the state’s prison system. Biographer Arnold Rampersad has written that by the time the 48th Annual NAACP Convention was held in Detroit, in June, Robinson had been transformed by his experience working for the organization. “I sometimes find it hard to remember what my life was like just a brief year ago,” he told the convention crowd on June 30.9

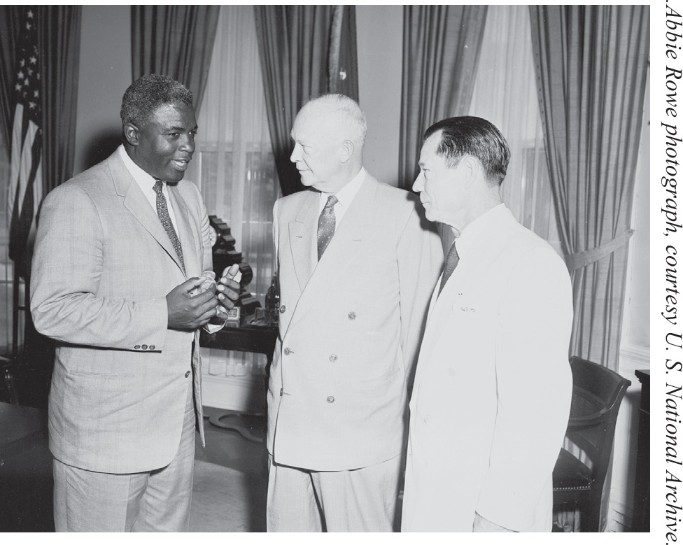

Jackie Robinson at the White House, with U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower and comedian Joe E. Brown on November 5, 1957.

On September 4, 1957, Arkansas’s Democratic Governor Orval Faubus, in opposition to the federally mandated desegregation of public schools, utilized the Arkansas National Guard to block nine African American students from integrating Little Rock Central High School. Six days later, Eisenhower drew Robinson’s ire when he preached “patience” on integration in an address to a group of Rhode Island Republicans.10 In a pointed September 13 response to the president, Robinson wondered to whom Eisenhower was referring when he urged patience, while drawing attention to the fact that the events in Little Rock were useful “material” for America’s enemies abroad.11 When on September 24 Eisenhower finally ordered the deployment of the Army’s 101st Airborne Division to quell the harassment and violence, Robinson, who was often just as quick to offer praise as he was criticism, responded the following day with a letter congratulating the president on the “positive position” he took.12

The stick-and-carrot criticism and praise of Eisenhower over the crisis in Little Rock was emblematic of an approach that, with few exceptions, Robinson maintained throughout his political life. Disagreements were seldom personal, and he often reserved his harshest criticism for those on whom he placed his highest expectations. For Robinson, personal relationships usually trumped party, and if he believed a candidate or elected official was right or wrong, particularly on matters pertaining to civil rights and American security, he had few qualms in saying so.

The year 1957 was a transformative one for Jackie Robinson. In his role as national chairman for the NAACP’s Freedom Fund drive, he achieved the organization’s million-dollar fundraising goal while also attracting a record number of life memberships.13 Recognition of his success came on January 6, 1958, when he was selected as one of three new members to the organization’s board of directors.14 Twelve days later, and not for the last time, he issued a denial to the press that he planned to seek political office himself, stating, “There is just not one kernel of truth to any such report. I have a job to do; but not in affiliation with a political party.”15 Robinson immersed himself in his work, and continued to maintain a relentless travel schedule that included an NAACP-sponsored speaking tour through the South in February. In the fall, he led 10,000 students on an October 25 march to the Lincoln Memorial in protest of the violence endured by African American children attempting integration in the South. When the Eisenhower administration refused a request to meet with some of the youth marchers, a thoroughly displeased Robinson asked, “How can you support these people when they treat you this way?”16 In one of his most publicly overt statements to date, he told a reporter that he had never considered himself a Democrat until October 25.17

Whereas professional baseball had a reserve clause, no such thing existed in politics and when Robinson turned his attention to the coming 1960 race to succeed Eisenhower, he was essentially a free agent. In January 1959 he began hosting an interview show on a small New York-based radio station, where his guests included such political luminaries as Governor Abraham Ribicoff of Connecticut, New York City Mayor Robert Wagner, and Eleanor Roosevelt. On May 25, 1959, he attended the Harlem YMCA Century Club Dinner to honor Elston Howard of the New York Yankees, and professional football player Jim Brown of the Cleveland Browns.18 The keynote speaker at the event was Democratic Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota. The senator’s progressive bona fides on issues of race dated back to his time as mayor of Minneapolis, when he helped procure enactment of the first municipal Fair Employment Practices Act in the United States.19 And his rousing, 10-minute speech demanding adoption of a civil-rights plank in the Democratic Party platform at the national convention in 1948 made him a hero to many progressives.20 In his autobiography, Robinson recounts having strongly admired Humphrey, calling him “a man who would rather be right morally than achieve the Presidency.”21 When 1959 drew to a close, Robinson had found his candidate in Humphrey. But perhaps because he was not entirely convinced of the senator’s overall electability, he kept a watchful eye on another expected contender to succeed Eisenhower: Vice President Richard Nixon.

By all accounts, Robinson was rather charmed by Richard Nixon at their first meeting, in Chicago in 1952. Introduced by Harrison McCall, president of the California Republican Assembly, Nixon recounted to Robinson in granular detail an unusual play Robinson was involved in during a 1939 football contest between UCLA and the University of Oregon. Recalling the introduction years later, McCall noted that “while Robinson had undoubtedly met a lot of notables in his career, nevertheless (McCall) was sure there was one person he would never forget.”22 In fact, Robinson and Nixon had struck up a friendship of sorts, and corresponded multiple times in the following years. By 1960, Robinson had come to view Nixon’s civil-rights rhetoric as notably more forward-leaning than the administration as a whole. Robinson was particularly drawn to the vice president’s penchant for framing America’s racial divide in international terms, noting that Nixon had “returned from a trip around the world, and he came back saying that America would lose the confidence and trust of the darker nations if she didn’t clear her own backyard of racial prejudice. Mr. Nixon made those statements for the television cameras and other media for all the world to hear.”23 Robinson, himself a staunch anti-communist, often employed similar arguments in his many speeches advocating for the benefits of equality.

The front-runner for the Democratic Party’s nomination heading into the Wisconsin primary was Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts. For a host of reasons, Robinson vehemently opposed his candidacy. He resented Kennedy’s decision to vote against the 1957 Civil Rights Act, which he considered a naked political attempt on the senator’s part to court Southern Democratic votes for an eventual Oval Office run. He was also particularly dismayed at the Massachusetts senator for having previously hosted segregationist Alabama Governor John Patterson and Sam Englehardt, president of the Alabama White Citizens Councils, to a June breakfast at his home in Georgetown. Commenting on the meeting, Robinson wrote, “Would you have me support a Kennedy who met with one of the worst segregationists in private, and then this man, the Governor of Alabama, comes out with strong support of Senator Kennedy?”24 But the Massachusetts senator won the Wisconsin primary by a comfortable margin over Hubert Humphrey. Better financed than his rival from Minnesota, Kennedy all but wrapped up the nomination with a commanding victory in the West Virginia primary on May 10. With Humphrey’s path no longer viable, Robinson turned his attention and support to the Nixon campaign.

During the Republican National Convention in Chicago in July 1960, Robinson applauded both an effort by Nixon to insert an aggressive civil-rights plank into the party’s platform that explicitly supported the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision, and his selection of progressive running mate Henry Cabot Lodge. In September Robinson was granted a leave of absence from Chock Full o’ Nuts to campaign full-time for Nixon. Like most everything he involved himself with, Robinson threw himself head-first into his support for the Republican candidate.

On October 19 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was one of 52 people arrested in downtown Atlanta for holding a sit-in at the lunch counters in the Magnolia Room of Rich’s department store. As author Steven Levingston has written, “Neither Kennedy nor Nixon wanted to risk alienating white Southern voters just weeks before the election by speaking out on behalf of King and the protesters.”25 Robinson, a close friend and frequent collaborator of King’s, desperately urged Nixon to issue a show of support for the jailed civil-rights leader, even providing the campaign with the phone number to the jail where his friend was being held.26 After a direct confrontation with Nixon on the matter, Robinson emerged with tears in his eyes to say, “He thinks calling Martin would be ‘grandstanding.’ Nixon doesn’t deserve to win.”27

For his part, John Kennedy found a way. On October 26 he placed a phone call to the governor of Georgia, Ernest Vandiver, to advocate for King’s release in a move Levingston describes as “so delicate that Kennedy told few, if any, of his advisors about his efforts.”28 The next day, under pressure from several close aides, he agreed to reach out to Coretta Scott King in order to express consternation over her husband’s predicament. In a call that lasted less than 90 seconds, Kennedy conveyed his concern over Dr. King’s confinement, and concluded by telling her, “If there is anything I can do to help, please feel free to call me.”29 The following day, on a $2,000 bond, her husband was released from the maximum-security state prison in Reidsville, where he had been recently transferred. Hours later at Peachtree-Dekalb Airport, a newly free Dr. King paid Kennedy a high compliment when he told gathered reporters, “For him to be that courageous shows that he is really acting upon principle and not expediency.”30 King’s father, a lifelong Republican and a Nixon backer, rescinded his endorsement while declaring, “I’ve got a suitcase full of votes, and I’m going to take them to Mr. Kennedy and dump them in his lap.”31

In the historically close 1960 race between Kennedy and Nixon, few can doubt that Kennedy’s intervention in King’s arrest aided his winning cause. In a race ultimately decided by fewer than 120,000 votes and two-tenths of a percentage point, the Democrats gained a seven-point swing among Black voters over their totals from four years earlier, and in several of the largest metropolitan areas, increased Black voter turnout proved decisive.32

While many of Robinson’s closest friends and family members were still struggling to understand his avid support for candidate Nixon, Robinson kept a skeptical eye trained on the words and deeds emanating from the new administration.33 Although he remained a consistent critic, in a manner commensurate with his critiques of the Eisenhower administration, when he found something to applaud, he applauded loudly. Robinson lauded Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy’s May 6, 1961, Law Day address at the University of Georgia in a letter, telling him, “I find it a pleasure to be proven wrong. May you continue to give your demonstrated leadership, which is so necessary at this time.”34 Likewise, when President Kennedy delivered his televised Report to the American People on Civil Rights, on June 11, 1963, where he laid out his administration’s intention to pursue legislation that ultimately comprised significant portions of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Robinson telegraphed the White House to declare the address “not the speech of a politician. It was the pronouncement of a stateman.”35

On September 9, 1962, two African-American churches in southwest Georgia were set ablaze in a racially motivated act of hatred. Robinson had only recently spoken at a voter registration drive in the area, and quickly traveled south to visit the sites. Telling reporters, “It really makes you want to cry deep down in your heart,” he agreed, at the behest of Dr. King, to chair a drive to raise funds to rebuild both churches. Robinson himself contributed $100, and reached out to other prominent African Americans such as Archie Moore and Floyd Patterson to solicit their support. In no time at all, donations began to arrive from the likes of William Black and Nelson Rockefeller, New York’s progressive Republican governor, who gave $10,000.

Nelson Rockefeller occupied a prominent position on the Republican Party’s left flank, particularly where civil rights were concerned. His great-grandparents were involved in the Underground Railroad, Rockefeller money had long flowed to Black higher education, he held an endorsement from the National Urban League, and he carried a third of New York’s overall African American vote to get elected governor in 1958. Robinson campaigned with Rockefeller in Harlem on behalf of the Nixon campaign in October 1960 and the governor later confided to Robinson his effort to persuade Nixon to intercede on Dr. King’s behalf, late in the campaign.36

Robinson spent a great deal of time in the fall of 1962 campaigning on behalf of candidates running in a host of state and local elections, which included multiple telethons for Richard Nixon’s failed race for California governor.37 He reserved his greatest effort for Nelson Rockefeller’s bid for re-election as New York’s governor. He attended multiple receptions and conducted campaign walks with the governor throughout Harlem and Brooklyn to generate support in African American communities.38 In November, Rockefeller comfortably defeated Democrat Robert M. Morgenthau by over 9 percentage points while also acquiring a dedicated ally in Jackie Robinson.39

President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas on November 22, 1963. Although Robinson had often been highly critical of the administration, he called the fallen president “a noble man,” in a December 7 column in the New York Amsterdam News. But in just a few short paragraphs, he quickly turned from sorrowful American to pragmatic politico, citing his own support for Rockefeller before asking his readers, “(W)here will the Negro stand?” if Lyndon Johnson and Barry Goldwater emerged as their party’s standard-bearers.40 As he looked to 1964, Robinson now viewed Rockefeller as the only man who offered a way forward for Black participation in the Republican Party.

On January 31, 1964, Robinson announced his resignation from Chock Full O’ Nuts, effective February 28. Four days later, Governor Nelson Rockefeller announced Robinson’s hire as one of six deputy directors for his presidential campaign team, calling him a “constructive competitor” with “the drive of a winner.”41 Rockefeller’s chief rival for the nomination was Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater, whose brand of states-rights conservatism found few takers among Black Republicans. Author Leah Wright Rigueur wrote in The Loneliness of the Black Republican that Goldwater’s detractors frequently cited the senator’s tendency to “vote with the southern political bloc 67 percent of the time, his popularity with southern segregationists, and his vote against the 1964 Civil Rights Act.”42 For his part, Robinson thought Goldwater a bigot, insisting that any leader in the Black community who supported the conservative senator would be ostracized, since “(t)he Negro is not going to tolerate any Uncle Toms in 1964.”43

Goldwater secured the nomination at the party’s national convention held July 13-16, 1964, at the Cow Palace in Daly City, California, just south of San Francisco. Robinson attended as a special delegate for Rockefeller, but with only 15 delegates and 28 alternates, African Americans comprised less than one percent of the total convention body.44 The convention was marred by violence and numerous displays of racial intolerance. In his description of the scene in a column in August, Robinson told his readers, “I would say that I now believe I know how it felt to be a Jew in Hitler’s Germany.”45 Robinson’s response was to co-found the National Negro Republican Assembly, an organization “characterized by a demand that the party recognize and address racial equality, integrate the mainstream machine, promote black advancement, and champion liberal and moderate Republican philosophies.”46 On August 14, Robinson wrote a letter to Democratic vice presidential candidate Hubert Humphrey volunteering his services for the ticket, an effort he believed necessary to “save the country.”47

Lyndon Johnson won 44 states and cleared 60 percent of the popular vote in a landslide win over Goldwater. He did so with a full 94 percent of the Black vote, as Goldwater managed victories in just six states, most of which had not gone Republican since Reconstruction. While the Arizona senator had failed to win the presidency, his campaign would serve as a template of sorts in the coming years for Republican outreach to white Southern voters long the provenance of the Democratic Party. For his part, Robinson’s defection made him the brunt of some criticism on the right, particularly from noted conservative columnist William F. Buckley.48 Nevertheless, Robinson remained hopeful. If he could help Rockefeller get re-elected in 1966, it would place the governor in good standing to once again pursue the Republican nomination in 1968 and perhaps rescue the party from the most extreme elements.

On February 7, 1966, Rockefeller hired Robinson to serve as a special assistant to the governor for community affairs. In media reports announcing the hiring, Robinson described his anticipated duties as “bringing the remarkable Rockefeller record to the attention of minority groups throughout the state.”49 That same month, he declined an offer from New York Mayor John Lindsay to serve on a commission on athletics, calling himself a “Rockefeller Republican” and the 1966 elections “(t)he most important in the history of the Negro people.”50

When the campaign got underway, Robinson worked tirelessly, describing, the “day to day, almost around the clock” effort as one of the “most rewarding experiences” of his life.51 His efforts paid off on Election Day when Rockefeller defeated Democrat Frank D. O’Connor by a margin of nearly 400,000 votes. Robinson biographer Arnold Rampersad has called Robinson’s involvement the “crowning moment of his career as a political operative.”52 Robinson also took heart in the victory of moderate Massachusetts Republican Edward Brooke, the first African American elected to the United States Senate by popular vote. He hoped the victories of Rockefeller and Brooke were evidence that the Republican Party could remain a viable option for Black voter participation. Nevertheless, he remained wary, noting rising conservative star Ronald Reagan’s election as governor in California by remarking, “In my book, Ronald Reagan is as bad news for minority people as Governor Rockefeller is good news.”53

While Robinson certainly had ambitious plans for Nelson Rockefeller in 1968, the first half of the year began on a somber note when his son, Jack Jr., was arrested on drug-possession charges in early March. Jack Jr. had enlisted in the US Army in March 1964, and earned a Purple Heart when he was wounded in an ambush in Vietnam on November 19, 1965. Honorably discharged the next year, he found life difficult in his return home. In a response to reporters’ questions before posting bail for his son, Robinson gloomily remarked, “He fought in Vietnam and was wounded. I’ve had more effect on other people’s kids than on my own.”54 On April 4 tragedy struck not only the Robinson family, but also the rest of the nation when the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. For Robinson, it was a tremendous personal loss, as he considered King a dear friend, mentor, and ally. Calling it “the most disturbing and distressing thing we’ve had to face in a long time,” he expressed grave concerns over the prospect of violent repercussions.55

President Lyndon Johnson, mired in a seemingly unwinnable war in Vietnam, shocked the nation when on March 31 he announced he would not seek another term in November. On April 5 his vice president and expected contender Hubert Humphrey wrote Robinson to offer his condolences for Dr. King’s passing and to solicit support for his campaign. Robinson responded the following month that while he considered the vice president “one of the best qualified men” he knew, he would only offer an endorsement if Nelson Rockefeller failed to capture the Republican nomination.56 On June 23 Robinson invited Black newspaper publishers and editors to his home in Stamford, Connecticut, to preach African American support for Rockefeller against Richard Nixon. In the ensuing years following his loss in the 1962 California governor’s race, Nixon had worked tirelessly raising money and campaigning on behalf of the Republican Party in dozens of races across the country. By 1968 there was a sense among many Republicans that he had earned another opportunity to claim the nomination. But Robinson considered Nixon’s failure to denounce Goldwater four years earlier as a personal betrayal, and, reading the tea leaves, saw clearly that a Nixon candidacy would no doubt benefit from Goldwater’s supporters.

The 1968 Republican National Convention was held in Miami Beach, Florida, August 5-8. Robinson, still partially recovering from a small heart attack suffered in June, did not attend. With little drama, Nixon secured the nomination while selecting Maryland Governor Spiro T. Agnew as his running mate. The selection of Agnew only served to further infuriate Robinson, as reports had surfaced that Nixon had allowed segregationist Southern Senator Strom Thurmond veto power over his selection.57 On August 11, appearing on the NBC television program Searchlight, Robinson announced that he was resigning from Governor Rockefeller’s staff to campaign full-time for the Democratic nominee. He accused Nixon of “prostituting himself to the bigots in the south” and declared, “I’m a black man first, an American second, and then I will support a political party-third.”58 On October 7 Robinson made an appearance with Democratic Governor Richard Hughes in Newark, New Jersey, and accused Nixon of competing for the same votes as segregationist Alabama Governor George Wallace, running as an independent. In the closing weeks of the contest, Robinson campaigned relentlessly throughout the Midwest.

On November 5, 1968, Richard Nixon defeated Hubert Humphrey by more than half a million votes to become America’s 37th president. His election was the continuation of a seismic shift in American politics as the Republican Southern strategy,” which sought to appeal to the racial grievances of White Southerners finally culminated in Ronald Reagan’s election as president in 1980. For Robinson, the 1968 campaign served as a bookend of sorts. His sharp turn against the Republican Party, his deteriorating health, and a number of significant personal setbacks rendered him largely a nonfactor politically for the remainder of his life. In 1970 he offered his support to Democrat Charles Rangel, who managed a primary defeat of longtime Robinson rival Adam Clayton Powell Jr. for the opportunity to represent New York’s 18th Congressional District in Harlem. Robinson died on October 24, 1972, just two weeks before Richard Nixon won re-election in a landslide over Democrat George McGovern.

The story of Jackie Robinson’s political odyssey is not only his story. It is also the story of an America undergoing a series of rapid-fire changes amid a seismic shift in its political tectonics. Any assessment of his political life practically demands that it be filtered through his extensive work in the civil-rights movement. He reserved his endorsements for candidates he sincerely believed counted the best interests of Black America, and by extension, all of America, high among their priorities. Although he held a reputation as a Republican, he did not wield party affiliation as a disqualifier. He was willing to work with anyone who was willing to work with him for the benefit of the country, and for his people. Modern-day attempts to frame Robinson’s politics in ultra-contemporary terms miss the point entirely. Robinson’s brand of politics, as well as the goals it aimed to achieve, were almost entirely relationship-based, from his early friendship with Nixon to his enduring professional and personal friendship with Nelson Rockefeller. If Robinson were still alive today, it seems an almost certainty that he would still be working tirelessly for racial equality. Whether or not he would find today’s Republican Party the ideal vehicle for that work is highly questionable. In a very real sense, Jackie Robinson never endorsed Nixon or Rockefeller because he was a Republican. Rather, it is more accurate to say that Robinson was a Republican because he endorsed Nixon and Rockefeller.

JEFF ENGLISH is a graduate of Florida State University and a lifelong Chicago Cubs fan. He lives in Tallahassee, Florida, with his lovely wife, Allison, and their twin boys, Elliott and Oscar. He has contributed to multiple SABR books including Mustaches and Mayhem: 1972-74 Oakland A’s, The 1986 Boston Red Sox: There Was More Than Game Six, and A Pennant for the Twin Cities: The 1965 Minnesota Twins.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the following:

Books

Tygiel, Jules. Extra Bases: Reflections on Jackie Robinson, Race, and Baseball History (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002)

Articles

Farrington, Joshua D. “Evicted from the Party: Black Republicans and the 1964 Election,” Journal of Arizona History 61, no. 1 (2020): 127-148.

Khan, Abraham. “Jackie Robinson, Civic Republicanism, and Black Political Culture,” Sports and Identity (2013): 83-105.

Rutkoff, Peter M. “Introduction – Jackie Robinson: Baseball, Brooklyn, and Beyond,” in Peter M. Rutkoff, ed., The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 1997 (Jackie Robinson) (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2015), 3.

Wisensale, Steven. “The Black Knight: A Political Portrait of Jackie Robinson.” In Peter M. Rutkoff, ed., The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 1997 (Jackie Robinson) (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2015), 189.

Notes

1 “Political Vacuum,” Hartford Courant, February 3, 1953: 10.

2 Michael Long, Beyond Home Plate (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2013), xxiii.

3 Long, Beyond Home Plate, 127.

4 William F. Buckley, “Robinson’s GOP Bolt Is Nothing Original,” Tennessean (Nashville), August 19, 1969: 12; Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson (New York: Ballantine, 1997), 340.

5 David Naze. Reclaiming 42: Public Memory and the Reframing of Jackie Robinson’s Radical Legacy (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019), 75.

6 “Jackie Robinson Heads ’57 Drive of Freedom Fund,” Boston Globe, January 7, 1957: 13.

7 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made (New York: Harper Collins, 1995), 126.

8 Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/jackie-robinson-baseball/articles-and-essays/baseball-the-color-line-and-jackie-robinson/meet-the-press, accessed January 14, 2021.

9 Rampersad, 319.

10 “Eisenhower Asks Patience in Integration,” Newport (Rhode Island) Daily News, September 10, 1957: 1.

11 Michael Long, First Class Citizenship: The Civil Rights Letters of Jackie Robinson (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2007), 40.

12 Long, First Class Citizenship, 41.

13 Long, First Class Citizenship, 315.

14 “18 Elected to NASCP???? NAACP? Nat’l Board,” Black Dispatch (Oklahoma City), January 17, 1958: 3.

15 “No Politics for Jackie,” Star Tribune (Minneapolis) February 1, 1958: 9.

16 “Randolph: DC March a Success,” New York Age, November 1, 1958: 35.

17 Rampersad, Jackie Robinson, 336.

18 “Sports Achievers,” Press and Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), May 26, 1959: 30.

19 Rampersad, Jackie Robinson, 341.

20 “Humphrey Sparks Convention,” Minneapolis Star, July 15, 1948: 7.

21 Robinson, I Never Had it Made, 136.

22 Long, First Class Citizenship, 26.

23 Robinson, I Never Had it Made, 135.

24 Steven Levingston, Kennedy and King: The President, the Pastor, and the Battle Over Civil Rights (New York: Hachette Books, 2017), 4.

25 Levingston, Kennedy and King, 75.

26 Rampersad, Jackie Robinson, 351.

27 Rampersad, Jackie Robinson, 351.

28 Levingston, Kennedy and King, 87.

29 Levingston, Kennedy and King, 88.

30 Levingston, Kennedy and King, 91.

31 Joshua D. Farrington, Black Republicans and the Transformation of the GOP (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 111.

32 “Kennedy Reported Winning Bulk of Negro Vote in Big Key Cities,” Minneapolis Star, November 4, 1960: 3.

33 Long, First Class Citizenship, 128.

34 Long, First Class Citizenship, 127.

35 Long, First Class Citizenship, 172.

36 Rampersad, Jackie Robinson, 353.

37 “Tonight, on Channel 11,” Valley Times Today (North Hollywood, California), November 3, 1962: 19.

38 Rampersad, Jackie Robinson, 369.

39 Our Campaigns, https://www.ourcampaigns.com/ContainerHistory.html?ContainerID=258, Accessed January 17, 2021.

40 Long, Beyond Home Plate, 141.

41 “Robinson Named Rockefeller Aide,” The Record (Hackensack, New Jersey), February 5, 1964, 10.

42 Leah Wright Rigueur, The Loneliness of the Black Republican (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 48.

43 Leah M. Wright, “Conscience of a Black Conservative: The 1964 Election and the Rise of the National Negro Republican Assembly,” Federal History. 1 (2009): 33.

44 Wright, “Conscience”: 35.

45 Indianapolis Recorder, July 25, 1964: 2.

46 Wright, “Conscience”: 34.

47 Long, First Class Citizenship, 203.

48 William F. Buckley, “Baseball, Politics Aren’t the Same,” Arizona Republic (Phoenix), November 5, 1965: 6.

49 “Rocky Hires Jackie,” New York Daily News, February 8, 1966: 34.

50 “Robinson Rejected Post,” Ithaca Journal, February 10, 1966: 14.

51 Rampersad, Jackie Robinson, 409.

52 Rampersad, Jackie Robinson, 409.

53 Rampersad, Jackie Robinson, 409.

54 Rampersad, Jackie Robinson, 423.

55 “Robinson Comments,” Quad-City Times (Davenport, Iowa), April 5, 1968: 4.

56 Long, First Class Citizenship, 277.

57 “Jackie Robinson Quits Rocky and Slides to Dems,” New York Daily News, August 12, 1968: 3.

58 “Jackie Robinson Quits Republicans,” News-Palladium (St. Joseph, Michigan), August 12, 1968: 7.