Philadelphia’s Other Hall of Famers

This article was written by Steven Glassman

This article was published in The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly (Philadelphia, 2013)

Many Baseball Hall of Fame inductees are associated with the American League Philadelphia Athletics and Philadelphia Phillies by way of career accomplishments, or by wearing the team ball cap on their Hall of Fame plaque. Many others in the Hall have connections to the city of Philadelphia and the city’s baseball teams since the 1860s. They fit into any of the following categories:

- Philadelphia-born

- Nineteenth-century professional-league team members (National Association—Athletics and White Stockings; American Association— Athletics; Union Association—Keystones; and/or Players League—Quakers)

- Negro League teams (Big Gorhams, Cuban Giants, Excelsiors, Giants, Pythians, Quaker Giants, Stars, and X-Giants)

- Employed by Athletics and/or Phillies parent club in a non-playing capacity

- Played in Athletics and/or Phillies minor league farm systems

- Ford C. Frick Award, J.G. Taylor Spink Award

- Inducted into other professional sports Halls of Fame (e.g. Basketball, Football, Ice Hockey)

This article expands upon a 2001 oral presentation made by the author at a Connie Mack Chapter meeting. Originally, there were 12 players mentioned in this presentation. Since then, additional names have been inducted and new information has been discovered through further research.

PHILADELPHIA-BORN

PHILADELPHIA-BORN

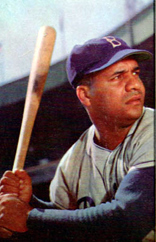

Roy Campanella (1969 Baseball Writers Association of America [BBWAA]): Campanella is the only Philadelphia-born player to be voted into the Baseball of Hall of Fame by the BBWAA. He was born on November 19, 1921, in the Germantown section of the city, and later moved to Nicetown.

According to his SABR BioProject article by Rick Swaine, “he attended Gillespie Junior High and Simon Gratz High School.”* Campanella briefly tried Golden Gloves boxing. He also played baseball, basketball, and football during his public school years. The Phillies invited Campanella for a tryout while he was in high school, but “the invitation was rescinded when the Phils discovered he was black.”

* He did not finish high school. The Bacharach Giants, a semi-pro team, offered Campanella his first professional contract when he was 15. He was later signed by the Baltimore Elite Giants of the Negro National League “to spell veteran receiver and manager Biz Mackey on weekends.”

Joseph “Joe” McCarthy (1957 Veterans Committee): “McCarthy was born in Philadelphia on April 21, 1887,” according to his SABR BioProject article. He grew up in Germantown and played baseball for “his grammar school team as well as a local team in Germantown.” McCarthy did not go to high school, but he “was productive enough to be offered a scholarship to Niagara University to play baseball in the fall of 1905.”

Effa Manley (2006 Negro Leagues Committee): Manley was born in Philadelphia on March 27, 1897, and grew up in the Germantown section of the city.

NINETEENTH CENTURY MAJOR-LEAGUE TEAM MEMBERS

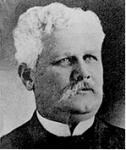

Adrian “Cap” Anson (1939 Veterans Committee): Anson was signed by the Athletics of the National Association after the last-place Forest City team disbanded following the 1871 season. He played every position except pitcher. Before the Chicago White Stockings signed Anson after the 1875 season, he was the franchise leader in batting average (.363), hits (384), singles (327), runs scored (248), and walks (29). According to David Fleitz, who wrote about Anson for the SABR BioProject, “The hard-hitting utility man quickly became one of Philadelphia’s most popular athletes. While he was playing for the Athletics, he dated Virginia Fiegal. The daughter of a saloon owner, she was about 13 or 14, and Anson was 20 years old. Despite some obstacles, he got Virginia’s father’s approval to marry. Virginia and ‘Cap’ Anson had seven children (four daughters and three sons). Co-authors William E. McMahon and Robert L. Tiemann wrote about Anson in SABR’s Baseball’s First Stars: “A salary offer of $2,000 induced Anson to sign with Chicago in 1876, a move his new bride, a Philadelphia girl, objected to. Adrian offered $1,000 to buy out his contract, but White Stockings owner William Hulbert held him to his commitment, and Anson began a 22-year tenure in Chicago.”*

William “Candy” Cummings (1939 Old Timers Committee as a Pioneer): Cummings became a member of the Philadelphia Whites of the National Association in 1874 after leaving the New York Mutuals. He pitched nearly every inning for the Whites, throwing 483 of the team’s 522 innings, registering a 28–26 won-lost record in his only season for the Whites. He struck out six straight Chicago White Stockings on June 15, 1874.

Wilbert Robinson (1945 Old Timers Committee as a Manager): Robinson, a catcher, played 372 games for the Athletics of the American Association from 1886–90. He came to the Athletics on the recommendation of Arthur Irwin to Bill Sharsig after Irwin saw Robinson play at Haverhill of the Eastern New England League in 1885. In the book Uncle Robbie, Irwin “was impressed by the young catcher’s ability to handle his pitchers and direct his infielders during a game.”* Robinson stole a career-best 33 bases as a rookie in 1886 and hit as high as .244 in 1888. While playing for the Athletics, he married Mary O’Rourke, a widow with two daughters. After they were married, Wilbert Jr. was born on June 20, 1890, in Philadelphia. Wilbert Sr. signed as a free agent with the Baltimore Orioles late in the 1890 season.

George Wright (1937 Centennial Committee as a Pioneer): Wright moved to Philadelphia from New York in 1865. The teenage Wright, according to his biography in Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia, “was both a pro for the Philadelphia Cricket Club and shortstop for the Philadelphia Olympians.”* His “amateur” status was not affected by his job with the cricket club because it was considered a teaching position. Wright returned to New York in 1866.

NEGRO LEAGUES

Oscar Charleston (1976 Negro Leagues Committee): Charleston was a member of the Philadelphia Stars of the Negro National League (1941–44, 1947–50). He was a first baseman-manager during his first two seasons with the Stars and then was primarily a coach under manager Homer “Goose” Curry during his next two campaigns. In his final four seasons, he was the manager. Two of his players, James “Bus” Clarkson (1952) and Harry “Suitcase” Simpson (1951–53, 1955–59), became major leaguers. He also managed future Hall of Fame pitcher Leroy “Satchel” Paige in 1950. Charleston died on October 5, 1954, in Philadelphia following a stroke, making him one of four Hall of Fame inductees to pass away in Philadelphia. The other three are pitcher “Chief ” Bender (Class of 1953) on May 22, 1954, shortstop George Davis (Class of 1998) on October 17, 1940, and manager Connie Mack (Class of 1937) on February 8, 1956.

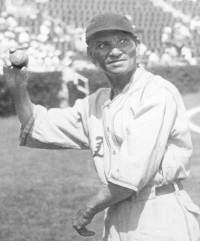

Andrew “Rube” Foster (1981 Veterans Committee): Foster was an outfielder and right-handed pitcher for the Philadelphia Giants from 1904 through 1906. Foster came to the Giants from the Cuban X-Giants following the 1903 season and was paid $90.00 per month. During the 1904 regular season, he struck out 18 batters in a game against the Trenton Y.M.C.A. Foster also defeated another “Rube,” Rube Waddell of the Philadelphia Athletics, and threw some no-hitters. In a 1904 postseason series versus his former team, Foster won two games and hit over .400 in the three-game affair. On September 1, at Inlet Park in Atlantic City, New Jersey, he struck out 18 hitters and contributed three hits in the 8–4 Game 1 win. In the third and deciding game, on September 3, Foster struck out five in the 4–2 victory. He also contributed toward the Giants’ repeat in 1905, and third straight in 1906. During the winter of 1906, Foster won nine games in Cuba, but in 1907 he became a player-manager for the Leland Giants in Chicago after a salary dispute.

Ulysses “Frank” Grant (2006 Negro Leagues Committee): Grant played his final two baseball seasons in Philadelphia for the 1902 and 1903 Giants, batting right and playing second base. He hit .222 in the 1903 playoffs versus the Cuban X-Giants.

John “Pete” Hill (2006 Negro Leagues Committee): The left-handed hitting outfielder came with Foster from the Cuban X-Giants. He was contributing member of the Giants’ 1904–06 championship teams, and was a leading batter in 1906. He hit over .300 in Cuba in the winter of 1905 and joined Foster in 1907 with the Leland Giants.

Raleigh “Biz” Mackey (2006 Negro Leagues Committee): Mackey’s first stint in Philadelphia was as a shortstop third baseman-catcher for the Philadelphia Royal Giants in the winter of 1925. He returned to Philadelphia as a catcher for three seasons in his mid-thirties (1933–35) for the Stars of the Negro National League. In the 1934 playoffs versus the Chicago American Giants, Mackey hit .368 to help the Stars to their only championship during their 20-year run (1933–52).

Leroy “Satchel” Paige (1971 Negro Leagues Committee): Paige was the first player inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Negro Leagues Committee. He had two brief stints with the Philadelphia Stars in 1946 and 1950, was signing a one-month contract in his second stint. He “pitched four innings and allowed three hits as the Stars beat the Brooklyn Bushwicks in an exhibition game in his first game back with the Stars.”* Paige also played three seasons (1956–58) for the International League Marlins, the Philadelphia Phillies’ top minor-league affiliate, in Miami, Florida. The Marlins were owned by Bill Veeck and Paige proved to draw quite a crowd—he was paid $15,000 to play for Miami. In one of his appearances, on August 7, 1956, 57,213 Miami Stadium patrons (then a minor league record) saw the 50-year-old hit a double and beat the Columbus Jets 6–2. He was 31–22 in 105 appearances (33 starts) in three seasons with the Marlins, with a 2.41 ERA in 340 innings. He led the Marlins in appearances with 37 in 1956, and his 27 relief appearances and 11 victories were third on the team. In 1957, Paige was second on the team with 32 relief appearances and third with 10 wins. Despite his three-year success with Miami, the Phillies never called him up to the parent club or purchased his contract.

D. Louis Santop (2006 Negro Leagues Committee): Santop, who played catcher, was a member of the 1909 and 1910 Philadelphia Giants. He died in Philadelphia on January 6, 1942.

Norman “Turkey” Stearnes (2000 Veterans Committee): Stearnes played outfield for the 1936 Philadelphia Stars. In his only season for the team, according to Baseball-Reference.com, he led the Stars in many hitting categories. After one season in Philadelphia, he returned to the Chicago American Giants in 1937.

Solomon “Sol” White (2006 Negro Leagues Committee): White wrote the book Sol White’s Official Base Ball Guide in 1907 while he was a member of the Philadelphia Giants. His SABR BioProject article notes, “This is the work which helps to define White the ball player, the historian and the man.” In addition to the Giants (1902–09), he was also a member of the Big Gorhams (1891) and the Quakers (1909). White had his best success with the Giants, winning three consecutive championships with teams that featured future Hall of Famers “Rube” Foster, Charlie Grant, Pete Hill, “Pop” Lloyd, and Louis Santop. White, along with Harry Smith and Philadelphia Item sports editor H. Walter Schlichter, formed the Giants. In his first five seasons, he was a player-manager, then was strictly a manager in his final two. He was also a player-manager for the Quakers before the team disbanded during the 1909 season. By 1903, he began paying his players $60–90 per month. Following the 1909 season, White was “fed up with Schlichter’s penny-pinching and seeing Foster steal so many of his players.”* He returned to New York, accepting an offer to manage the Brooklyn Royal Giants in 1910.

Solomon “Sol” White (2006 Negro Leagues Committee): White wrote the book Sol White’s Official Base Ball Guide in 1907 while he was a member of the Philadelphia Giants. His SABR BioProject article notes, “This is the work which helps to define White the ball player, the historian and the man.” In addition to the Giants (1902–09), he was also a member of the Big Gorhams (1891) and the Quakers (1909). White had his best success with the Giants, winning three consecutive championships with teams that featured future Hall of Famers “Rube” Foster, Charlie Grant, Pete Hill, “Pop” Lloyd, and Louis Santop. White, along with Harry Smith and Philadelphia Item sports editor H. Walter Schlichter, formed the Giants. In his first five seasons, he was a player-manager, then was strictly a manager in his final two. He was also a player-manager for the Quakers before the team disbanded during the 1909 season. By 1903, he began paying his players $60–90 per month. Following the 1909 season, White was “fed up with Schlichter’s penny-pinching and seeing Foster steal so many of his players.”* He returned to New York, accepting an offer to manage the Brooklyn Royal Giants in 1910.

Ernest “Jud” Wilson (2006 Negro Leagues Committee): Wilson played for the Philadelphia Tigers in 1928 and the Stars from 1933 through 1939. He led the Stars with a .400 average in the 1934 playoffs versus the Chicago American Giants, and became the team’s player-manager for one season in 1937. Wilson made multiple appearances in the East-West All-Star Game. He returned to the Homestead Grays for the 1940 season and spent the remainder of his career there.

EMPLOYED BY ATHLETICS OR PHILLIES PARENT CLUB IN A NON-PLAYING CAPACITY

William “Judy” Johnson (1975 Negro Leagues Committee): Prior to the 1951 season, Johnson became the first African American scout hired by the Philadelphia Athletics, and was assigned to scout major-league ready Negro League players. One of his recommendations was to hire Indianapolis Clowns second baseman Hank Aaron for $3,500. The recommendation was rejected because the Athletics felt signing him was too expensive, and it wasn’t the only one Connie Mack rejected. In 1954, the Athletics hired Johnson as the first African American coach for the Athletics. This came with a new responsibility: “Helping these players adjust to the major leagues on the field and the trials off the field.”* Two of these players were pitcher Bob Trice and infielder Vic Power. Johnson left the team before it moved to Kansas City. The Phillies hired him in 1961 and one his signees, Richie Allen, reached the major leagues. According to his biography in Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia, “Johnson’s understanding of the game was utilized every year in spring training as the Phillies brought him south to coach the young players.”* He scouted for the team through the 1974 season.

Paul Waner (1952 BBWAA): In the early 1950s, Waner published a pamphlet entitled, Paul Waner’s Batting Secrets. He was hired by the Milwaukee Braves in 1954 as the hitting instructor for the parent club and its minor-league affiliates. Poor health forced him to leave the Braves in July of 1958. The St. Louis Cardinals hired him as a hitting advisor on July 26, 1958 and he held that position through the 1959 season, working with the organization’s minor-league hitters. The Phillies hired him on January 7, 1960, and again on May 30, 1965 in the same capacity he served with the Braves. On August 29, 1965, he died in his home in Sarasota, Florida due to pulmonary emphysema and pneumonia.

PLAYED IN ATHLETICS OR PHILLIES MINOR LEAGUE FARM SYSTEMS

Thomas “Tommy” Lasorda (1997 Veterans Committee as a Manager): Lasorda, a left-handed pitcher, was signed out of Norristown High School as an amateur free agent by the Phillies in January 1945 and began his professional career with the Concord Weavers of the Class D North Carolina State League. Lasorda appeared in 27 games (13 starts), won three times, and compiled a 4.09 ERA. However, as a hitter he batted .274 in 67 games. Pitching for the Schenectady Blue Jays of the Class C Canadian-American League, he appeared in 32 games (18 starts), striking out a career-best 195 batters in 192 innings and winning nine games, but he walked a career-worst 153 batters (tied for second in the league) and led the league with 20 wild pitches. Lasorda set a league record with 25 strikeouts in a 15-inning game versus the Amsterdam Rugmakers on May 31, 1948. He also broke Earl Jones’ league-record 22 strikeouts (in nine innings).

Anthony “Tony” Lazzeri (1991 Veterans Committee): Lazzeri became the manager of the Class AA Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League in June 1939 after he was released by the New York Giants. The Maple Leafs played as an unaffiliated team during the 1939 season before becoming an affiliate of the Philadelphia Athletics for the 1940 season. Among the notable players who played for Lazzeri in 1940 were pitchers Dick Fowler and Phil Marchildon. Lazzeri was released by Toronto following the 1940 season after the Maple Leafs finished in last place with a 57–101 record, 38 1/2 games behind the Rochester Red Wings.

Henry “Heinie” Manush (1964 Veterans Committee): Following a 56–83 season for the Class A Eastern League Scranton Miners in 1944, the team announced in November that Manush would not be back for the 1945 season. Manush spent five seasons in the Boston Red Sox farm system. He managed the Class C Martinsville Athletics of the Carolina League to a 69–67 record, a third place finish, and a playoff berth—the Athletics lost to the Danville-Schoolfield Leafs in the best-of-seven semifinals four games to two. Before Game 6, according to The Sporting News (September 21, 1945), “Martinsville fans presented Manager Heinie Manush with a gold watch and his players gave him a pen and pencil set.”* Two of Manush’s players, first baseman Jerome Gutt and outfielder Rudolph Adkins, were named to the Carolina League All- Star team. Outfielder and native Philadelphian Tom Kirk, who shared the league lead with three other players with a dozen home runs, made a pinch-hit appearance for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1947. Manush became a Boston Braves scout in 1946.

FORD C. FRICK AWARD (BROADCASTING)

Timothy “Tim” McCarver (2012 Ford C. Frick Award): McCarver was acquired by the Phillies on October 7, 1969, from the St. Louis Cardinals with outfielders Byron Browne and Curt Flood and pitcher Joe Hoerner for infielders Dick Allen and “Cookie” Rojas and pitcher Jerry Johnson. McCarver started the season as the Phillies regular catcher until May 2, 1970, when a Willie McCovey foul sent him to the disabled list until September 1, causing him to miss 110 games. McCarver continued as the Phillies regular catcher for 1971 and the beginning of 1972. He was traded to the Montreal Expos for another catcher, John Bateman, on June 14, 1972. More than a week after he was released by the Boston Red Sox, the Phillies signed him as a free agent on July 1, 1975. He spent the remainder of his Phillies (and major-league) career as a backup to Bob Boone. The Phillies released McCarver following the 1979 season and he entered the broadcast booth. McCarver came out of the booth and was signed by the Phillies as a free agent on September 1, 1980, for the pennant drive, mostly as a pinch-hitter. He was released after the Phillies won the World Series and went back to broadcasting. McCarver was also best known as Steve Carlton’s personal catcher, working with him in 137 out of 168 games between July 12, 1975, and September 30, 1979.

Robert “Bob” Uecker (2003 Ford C. Frick Award): On October 27, 1965, the Phillies acquired Uecker from St. Louis Cardinals. Half of his 14 major-league home runs and 74 RBIs came as a member of the Phillies. In 1966, as a catcher he set career bests with 62 starts, 542 1/3 innings caught, while throwing out 21 baserunners attempting to steal, and recording five pickoffs. Uecker also threw out a career-best 40 percent of baserunners attempting to steal on him in 1966. However, he got off to a very slow start in 1967, batting .100 in 20 at-bats over nine games through early May. After appearing in nine of the Phillies’ first 17 games, Uecker played nine of the next 31. He “improved” his batting average to .171 and was traded to the Atlanta Braves on June 6, 1967, for another catcher, Gene Oliver. Uecker finished the season with Braves and was released on October 6, 1967.

J.G. TAYLOR SPINK AWARD (JOURNALISM)

Timothy “Tim” Murnane (1978 J.G. Taylor Spink Award): Murnane joined the Athletics in 1873 after the Mansfield (Middletown, Connecticut) club folded the previous season. In his first season with the Athletics, Murnane did not hit well, as his .222 average and 13 strikeouts in 41 games were the worst among Athletics regulars. However, the center fielder walked eight times which tied fellow outfielder John McMullin for the team lead and was second to McMullin with eight steals. The right fielder-second baseman did not play as much (21 games) or hit as well (.207) for the Athletics in 1874, but he was part of the Athletics’ midseason European trip with the Red Stockings. According to his SABR BioProject article by Charlie Bevis, “For the 1875 season Murnane took advantage of the league’s mobility principle to negotiate with other clubs after fulfilling his one-year contract.” Murnane had a career season for the 1875 Philadelphia Whites, leading the team with 313 at-bats, posting a National Association best 30 stolen bases, and walking seven times. Murnane also shared the team lead with 69 games played and 71 runs scored, and was second on the club with 79 singles. Murnane played first base, center field, and second base in his only season with the Whites. After the National Association folded, he joined the Boston Red Stockings in the National League’s first season in 1876. After his playing career ended he wrote for the Boston Referee (his own publication), New York Clipper, and Boston Globe.

Timothy “Tim” Murnane (1978 J.G. Taylor Spink Award): Murnane joined the Athletics in 1873 after the Mansfield (Middletown, Connecticut) club folded the previous season. In his first season with the Athletics, Murnane did not hit well, as his .222 average and 13 strikeouts in 41 games were the worst among Athletics regulars. However, the center fielder walked eight times which tied fellow outfielder John McMullin for the team lead and was second to McMullin with eight steals. The right fielder-second baseman did not play as much (21 games) or hit as well (.207) for the Athletics in 1874, but he was part of the Athletics’ midseason European trip with the Red Stockings. According to his SABR BioProject article by Charlie Bevis, “For the 1875 season Murnane took advantage of the league’s mobility principle to negotiate with other clubs after fulfilling his one-year contract.” Murnane had a career season for the 1875 Philadelphia Whites, leading the team with 313 at-bats, posting a National Association best 30 stolen bases, and walking seven times. Murnane also shared the team lead with 69 games played and 71 runs scored, and was second on the club with 79 singles. Murnane played first base, center field, and second base in his only season with the Whites. After the National Association folded, he joined the Boston Red Stockings in the National League’s first season in 1876. After his playing career ended he wrote for the Boston Referee (his own publication), New York Clipper, and Boston Globe.

William “Bill” Conlin (2011 J.G. Taylor Spink Award): Conlin was born on May 15, 1934, in Philadelphia and was a 1961 Temple University graduate. The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin gave him his first journalistic opportunity. In 1965, The Philadelphia Daily News hired Conlin as the Phillies beat writer, a position he held through 1986. He was a Daily News sports columnist from 1987 through 2011 and was also a National League columnist for The Sporting News. Conlin wrote the books, The Rutledge Book of Baseball (Rutledge Press, 1981) and Batting Cleanup, Bill Conlin (Temple University Press, 1997).

INDUCTED INTO OTHER PROFESSIONAL SPORTS HALLS OF FAME

Edward “Eddie” Gottlieb (1972 Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame): Gottlieb, who was born in Kiev, Ukraine, grew up in Philadelphia, attending South Philadelphia High School and a Philadelphia teacher’s college. Gottlieb was heavily involved in African America baseball, booking and promoting games and selling equipment. In 1931, Pittsburgh Crawfords owner Gus Greenlee named Gottlieb as the Negro National League (NNL) booking agent. Gottlieb also formed a partnership with Ed Bolden to establish the Philadelphia Stars before the 1933 season, with most of the money invested coming from Gottlieb, not Bolden. In 1934, the Stars won their only Negro National League championship, led by future Hall of Famers Raleigh “Biz” Mackey and Ernest “Jud” Wilson. Gottlieb had multiple positions with the Stars (and the NNL): booking agent, owner, promoter, officer, and secretary. When major-league baseball was integrated in 1947, it affected Negro League baseball. Two majorleague and multiple minor-league teams in the tri-state area cut into the Stars’ attendance figures. Also, African- Americans playing for all-white semipro teams made black semipro teams an endangered species. This, and a number of factors, led to the end of the NNL in 1948. The Stars’ home ballpark, Parkside Park, was torn down and Gottlieb sold off some of his best players to organized baseball to help keep the Stars financially afloat. Gottlieb’s partner, Ed Bolden, died in December 1949. By 1950, Gottlieb had settled with Bolden’s daughter, Dr. Hilda Bolden Shorter, to purchase most of Ed’s shares, which were valued at $1,000 according to his will. Oscar Charleston was really running the team at that point, and attendance and gate receipts were dwindling badly by 1952. The Stars had the worst record and eventually dropped out of the Negro American League after the 1952 season ended. Hilda wanted to revive her father’s position with the Stars and bring the team back to the point where they could still financially succeed in Negro League baseball. However, the plans fell through and Gottlieb put the Stars up for sale for $10,000. No one wanted to buy the Stars, and Gottlieb announced the team was folding and its players could sign with anyone.

Gottlieb established, and was the coach for, the South Philadelphia Hebrew Associations (SPHAS) in 1918. They won multiple Eastern and American Basketball League Championships from the late 1920s through the 1940s. He also helped found the Basketball Association of America (BAA) in 1946, and his Philadelphia Warriors won the Association’s first championship in 1947. Gottlieb held multiple positions with the Warriors—owner, coach, general manager, and ticket seller. The NBA was merged out of the National Basketball League and the BAA, coming together through Gottlieb’s efforts. He remained the Warriors coach through 1955, winning two divisional titles, and the owner through 1956 when the team won its second title. Gottlieb was the NBA’s Rules Committee chairman for 25 years and the Association’s schedule maker for 30.

Alfred “Greasy” Neale (1969 Professional Football Hall of Fame): Neale was acquired by the Phillies in an offseason trade with the Cincinnati Reds. On November 22, 1920, he was acquired with pitcher Jimmy Ring for pitcher Eppa Rixey. The right fielder played 22 games for the Phillies, but hit .211 with one RBI. He was put on waivers by the Phillies and claimed by the Reds, his original team, on June 2, 1921, and finished his career with them in 1924. Neale coached the Philadelphia Eagles from 1941 through 1950. He changed the team’s offensive and defensive schemes, turning it around and winning three straight NFL Eastern Division Titles (1947–49), including the franchise’s first two league championships in 1948 and 1949. Some of the future NFL Hall of Fame players he coached included Chuck Bednarik, Pete Pihos, and Steve Van Buren. Altogether, Neale won 63 games and compiled a .594 winning percentage.

Clarence “Ace” Parker (1972 Professional Football Hall of Fame): Parker played football and baseball at Duke University. His head baseball coach at Duke was former Athletics pitcher Jack Coombs, and it was the Philadelphia Athletics that signed him. On April 30, 1937, in a 15–5 road loss to the Boston Red Sox, Parker hit a ninth-inning, pinchhit home run off Wes Ferrell in his first major-league atbat. He became the 12th major leaguer, and third in the American League, to accomplish that feat. Parker was also the first of two Philadelphia Athletics hitters to hit a home run in his first major league at-bat. His two best games were a pair of three-hit, four-RBI games (July 28, 1937, versus Cleveland and August 16, 1938, at Boston). Parker, who played mostly in the infield, played parts of two seasons with the Athletics, hitting .179 in 94 games. Parker was a 1936 All-American tailback at Duke and finished sixth in the Heisman Trophy voting before becoming the second-round draft choice of football’s Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1937 NFL Draft. He was either a first or second All-NFL from 1937 through 1940. He led the league with 865 passing yards in 1938, then in 1940, Parker paced the league with six interceptions and 146 interception return yards, 9 extra points, and 22 attempts, while placing second with 10 passing touchdowns. As a punter, he was third in the league with 49 punts and 1,875 yards. Not surprisingly, Parker was given the Joe F. Carr Trophy as the league’s 1940 Most Valuable Player.

Harry Stovey: Nineteenth-century player Harry Stovey, originally born with the last name Stowe, was born in Philadelphia on December 20, 1856. He made his amateur (Defiance Club) and professional baseball (Athletics of the League Alliance) debuts in Philadelphia in 1877. Stovey came to the Athletics of the American Association in 1883 after the Worcester club of the National League folded following the 1882 season. He played seven seasons for the Athletics (1883–89), including the 1883 championship campaign. Before he went on to play for the Boston Reds of the newly formed Players League in 1890, Stovey was the Athletics franchise leader in every offensive category, except for batting average.

He finished his American Association career as the all-time leader in homers (76) and runs scored (883), was second in total bases (1,654), and third in slugging (.483). He was also in the top 10 in games played (824), batting average, and hits (1,035). Stovey led the Association in runs scored four times, homers three times, and triples, total bases, and slugging twice each. He also averaged more than one run scored per game (1.07).

In his career as a whole, he led his league in home runs five times (10 times in the top five), runs scored four times (nine times in the top five), triples four times (five times in the top five), total bases three times (seven times in the top five), slugging three times (seven times in the top five), and stolen bases at least twice (at least four times in the top five). Stovey also led his league in doubles once, but was in the top five on five occasions. He never led in walks, but was in the top five four times. Unofficially, Stovey led his league in RBIs once, but was also in the top five on five occasions.

When Stovey retired, he was major-league baseball’s all-time home run leader with 122. He was also among all-time leaders in slugging percentage (.461), total bases (2,832), runs scored (1,492), doubles (347), and triples (174). Over his career Stovey averaged more than one run scored per game (1,492 runs in 1,486 games).

Stovey appeared on the BBWAA Veterans ballot once, in 1936, with other nineteenth century players, receiving six votes (7.7%) and tying for 14th on the ballot. Out of the 60 players who appeared, 31 are now in the Hall of Fame, including 15 of the 19 players who received six or more votes. Stovey did not appear on any more ballots.

Stovey is no stranger to SABR. On December 20, 1971, he finished 12th out of 66 pre-1952 eligible players in a survey of SABR Members (The results appeared in the 1974 Baseball Research Journal). Stovey and Pitcher Carl Mays, who finished eight votes ahead of Stovey, are the only players left on this ballot who are not in the Hall. In the 1977 Baseball Research Journal, players from the 1871–1911 were ranked in a survey of Hall of Fame candidates and Stovey finished fifth ahead of Vic Willis (sixth), Deacon White (ninth), and “Bid” McPhee (15th).

At the 2011 SABR convention in Long Beach, California, Stovey was selected by the Nineteenth Century Committee members as its Overlooked 19th Century Legend.

STEVEN GLASSMAN has been a SABR member since 1994 and regularly makes presentations for the Connie Mack Chapter. His previous SABR convention oral presentation was “Thank You for Your (Non-)Support” (SABR 42), and he’s also making his fourth poster presentation in the past five years. The Temple University graduate in Sport and Recreation Management has worked in the Sports Information field for Temple University, West Chester University, Albright College, and Rutgers University-Newark. He currently works as a full-time scoreboard operator for The Sports Network in Hatboro, PA. Steven is also a part-time volunteer Director of Sports Information for Manor College in Jenkintown, PA. Born in Philadelphia, Steven currently resides in Warminster, PA.

SOURCES

Books

Carter, Craig, Editor. Daguerreotypes, Eighth Edition. St. Louis: The Sporting News Publishing Co., 1990.

Clark, Dick and Lester, Larry, Editors. The Negro Leagues Book. Cleveland: The Society for American Baseball Research, 1994.

Dewey, Donald and Acocella, Nicholas. The New Biographical History of Baseball. Chicago: Triumph Books, 2002.

Gillette, Gary and Palmer, Pete, Editors. The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2008.

Hogan, Lawrence D. Shades of Glory. Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2006.

Holway, John. The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball’s History. Fern Park: Hastings House Publishers, 2001.

Ivor-Campbell, Frederick; Tiemann, Robert I.; and Rucker, Mark, Editors. Baseball’s First Stars. Cleveland: The Society for American Baseball Research, 1996.

Johnson, Lloyd and Wolff, Miles, et al. Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Third Edition. Durham: Baseball America, 2007.

Jordan, David M. Occasional Glory. Jefferson: McFarland and Company, Inc. Publishers, 2002.

Kavanagh, Jack and Macht, Norman. Uncle Robbie. Cleveland: The Society for American Baseball Research, 1999.

Koszarek, Ed. The Players League: History, Clubs, Ballplayers and Statistics. Jefferson: McFarland and Company, Inc. Publishers, 2006.

MacFarlane, Paul and Siegel, Barry. The Sporting News Hall of Fame Fact Book, St. Louis: The Sporting News Publishing Company, 1983.

Marazzi, Rich and Fiorito, Len. Baseball Players of the 1950s. Jefferson: McFarland and Company, Inc. Publishers, 2004.

Nemec, David. The Beer & Whiskey League: The Illustrated History of the American Association—Baseball’s Renegade Major League. Guilford: The Lyons Press, 2004.

Nemec, David. The Great Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Baseball, Second Edition. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2006.

Parker, Clifton Blue. Big and Little Poison. Jefferson: McFarland and Company, Inc. Publishers, 2004: 237-247, 264-283, 294-299.

Pietrusza, David; Silverman, Matthew; and Gershman, Michael, Editors. Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia. Kingston: Total Sports Publishing, 2000.

Ribosky, Mark. A Complete History of The Negro Leagues 1884-1955. New York: Kensington Publishing Corp., 2002.

Riley, James A. The Biographical Encyclopedia of The Negro Baseball Leagues. New York: Carroll and Graf Publishers, 1994.

Rosin, James. Philly Hoops: The SPAHS and Warriors. Philadelphia: Autumn Road Publishers, 2003.

Shiffert, John. Base Ball in Philadelphia: A History of the Early Game, 1831-1900. Jefferson: McFarland and Company, Inc. Publishers, 2006.

Taylor, Ted. The Ultimate Philadelphia Athletics Reference Book: 1901-1954. Xlibris, 2010.

Threston, Christopher. The Integration of Baseball in Philadelphia. Jefferson: McFarland and Company, Inc. Publishers, 2003.

Tiemann, Robert L. and Rucker, Mark, Editors. Nineteenth Century Stars. Cleveland: The Society for American Baseball Research, 1989.

Westcott, Rich. The Mogul: Eddie Gottlieb—Philadelphia Sports Legend and Pro Basketball Pioneer. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2008, 88-120.

Westcott, Rich and Campbell, Bill. Native Sons: Philadelphia Baseball Players Who Made The Major Leagues. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003.

Westcott, Rich and Bilovsky, Frank. The Phillies Encyclopedia, Third Edition. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004.

White, Sol. Sol White’s History of Colored Baseball. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

Journals

Davids, L. Robert, Editor. “Big Sam Belongs in Hall,” The Baseball Research Journal: Volumes 1 through 3 (1998), 55.

Holway, John B. “Judy Johnson,” The Baseball Research Journal 15 (1986), 62-64.

Lipset, Lew. “‘Grandpa’ was Harry Stovey,” The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History (Winter 1985), 84-85.

“Old Timers Survey for the Hall of Fame,” The Baseball Research Journal (1977), 117-118.

Websites

http://www.baseball-reference.com

http://www.paperofrecord.com

http://www.retrosheet.org

http://sabr.org/bioproject

“Cap Anson,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/9b42f875.

“Chief Bender,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/03e80f4d.

“Roy Campanella,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/a52ccbb5.

“Candy Cummings,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/99fabe5f.

“George S. Davis,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/95403784.

“Rube Foster,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/fcf322f7.

“Frank Grant,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/2f633c50.

“Judy Johnson,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/5c84de56.

“Tony Lazzeri,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/1b3c179c.

“Heinie Manush,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/17088fe1.

“Joe McCarthy,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/2c77f933.

“Tim Murnane,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/b2017f67.

“Satchel Paige,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/c33afddd.

“Wilbert Robinson,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/5536caf5.

“Paul Waner,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/9d598ab8.

“Sol White,” accessed February, 2013, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/2f9d1227.

National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum and Library, Paul Glee Waner Player File

2012 National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum Yearbook