More Whimpers Than Bangs: How Batters Perform When “It’s the World Series and they’re down to their final out”

This article was written by Steve Gietschier

This article was published in Fall 2013 Baseball Research Journal

How did the 2012 World Series end? It was Game Four in Detroit. The San Francisco Giants, up three games to none, scored a run in the top of the tenth on a single by Marco Scutaro to take a 4–3 lead. In the bottom of the tenth, closer Sergio Romo entered the game to face the Tigers. Austin Jackson struck out, pinch-hitter Don Kelly struck out, and then Miguel Cabrera came to the plate: strike one, ball one, strike two, ball two, foul, and then strike three looking. It was over. Cabrera, arguably the best player in the American League last year, made the final out.

Now, go back to the beginning. How did the World Series in 1903 end? It was Game Eight in Boston. Remember, this Series was best-of-nine. The Americans led the Pittsburgh Pirates, four games to three, and 3–0 after eight innings. In the top of the ninth, Bill Dinneen was on the mound. Fred Clarke flied to left, Tommy Leach flied to right, and then Honus Wagner struck out, swinging or looking, we do not know. (Sources disagree.) It, too, was over. The best player in the National League had made the final out.

We all know that baseball games lack an arbitrary end. No clock means that the participants determine not only when the game will end but also when it will not end. Sabermetrics recognizes this: “Don’t squander outs.” Kids know it, too: “Save me a time at bat.” Roger Angell perhaps put it best in The Summer Game, “Since baseball is measured in outs, all you have to do is succeed utterly; keep hitting, keep the rally alive, and you have defeated time. You remain forever young.”

We all remember that some of baseball’s greatest moments have come with one swing of the bat. Indeed, the term “walk-off” has fast become a cliché, having been applied not only to homers but also to singles, sacrifice flies, and even walks. Conversely, there are obviously thousands of instances when the offense fails and the game ends, maybe dramatically and maybe not, with a strikeout, a fly ball, a line drive, or a mesmerizing fielder’s choice at second.

But what about those times when the game doesn’t end, when the guy in the on-deck circle yells “Save me a lick,” and the batter does just that, when the announcer says, “They’re down to their final out,” and yet the game goes on? What about those at-bats that might end the entire World Series, but don’t? Cabrera could have tied Game Seven last year with one swing of the bat. Wagner’s task was more prosaic—keep the game going—and that’s what we’re studying here, those at-bats when one more out would be the final out of the World Series. Just how often have batters succeeded when failure would usher in the start of the off-season?

This essay was inspired not by the quick and surprising triumph of the Giants last fall—the only time that the final half-inning of the World Series included three straight strikeouts—but by the performance of the St. Louis Cardinals in 2011. They were down to their final out three times over two innings in Game Six against the Texas Rangers, and yet they survived and ultimately prevailed. In the ninth, they were down two runs with two on and two out when David Freese tripled to tie the score, 7–7. In the tenth, again down two runs, there were two on and two out before Texas walked Albert Pujols intentionally, and Lance Berkman singled to tie the score again. And, then, of course, Freese led off the eleventh with a walk-off home run. In fact, the Cards were not only down to their final out three times; they were down to their final strike three times, once in the ninth and twice in the tenth. And then they went on to win Game Seven, 6–2, making it look comparatively easy.

This essay was inspired not by the quick and surprising triumph of the Giants last fall—the only time that the final half-inning of the World Series included three straight strikeouts—but by the performance of the St. Louis Cardinals in 2011. They were down to their final out three times over two innings in Game Six against the Texas Rangers, and yet they survived and ultimately prevailed. In the ninth, they were down two runs with two on and two out when David Freese tripled to tie the score, 7–7. In the tenth, again down two runs, there were two on and two out before Texas walked Albert Pujols intentionally, and Lance Berkman singled to tie the score again. And, then, of course, Freese led off the eleventh with a walk-off home run. In fact, the Cards were not only down to their final out three times; they were down to their final strike three times, once in the ninth and twice in the tenth. And then they went on to win Game Seven, 6–2, making it look comparatively easy.

The 2011 Series was so dramatic that fans were forced to look back to 1986 when the New York Mets were also down to their final out three times in Game Six against the Boston Red Sox and to their final strike once. And they won, too. In that fateful Game Six, the Red Sox scored twice in the top of the tenth to take a 5–3 lead. In the bottom half of the inning, Wally Backman and Keith Hernandez made out before Gary Carter staved off elimination with a single. Kevin Mitchell, pinch-hitting for Rick Aguilera, also singled. Ray Knight singled, too, scoring Carter and sending Mitchell to third. Bob Stanley then threw a wild pitch that scored Mitchell and sent Knight to second. And then Mookie Wilson’s grounder got past Bill Buckner, and Knight scampered home with the winning run.

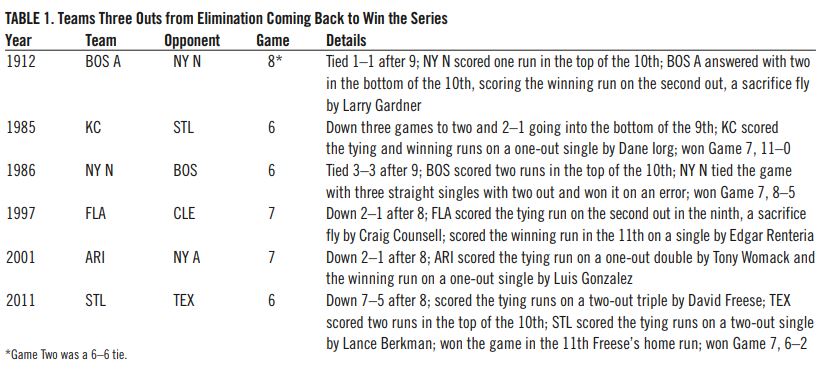

No other team has matched this brinkmanship. In fact, only four other teams have been three outs from elimination and come back to win the Series, but none went down to the final out. In Game Eight of the 1912 Series (Game Two was a 6–6 tie), the Red Sox scored two runs in the bottom of the tenth to defeat the New York Giants. In 1985 (the infamous Denkinger game), the Kansas City Royals scored twice in the bottom of the ninth against the Cardinals to win Game Six, 3–2, and went on to win Game Seven, 11–0. In 1997, the Florida Marlins tied the Cleveland Indians in the bottom of the ninth of Game Seven and won the Series with a run in the bottom of the eleventh. And in Game Seven in 2001, the Arizona Diamondbacks scored the tying run and the winning run in the bottom of the ninth against the New York Yankees. (See Table 1 for details.)

Those are the heroics, the “bangs,” if you will. Much more prevalent, naturally, are the “whimpers.” The composite batting average for all players in all World Series is .242, but faced with elimination, batters have hit only .211. Yogi Berra, fount of wisdom that he is, is a bit off: when a World Series elimination game reaches the ninth inning, it is almost always over before it’s over.

GAME FOUR

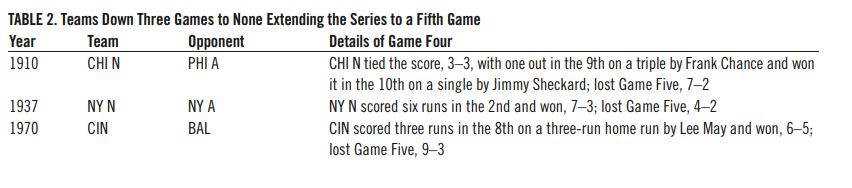

The first chance a batter has to confront the possibility that he might make the final out in the World Series is, of course, in Game Four when his team has already lost the first three games. There have been 24 Game Fours that have been elimination games. In three of them, the team on the short end managed to extend the Series just one more game before losing, but none of these three (the 1910 Chicago Cubs, the 1937 Giants, and the 1970 Cincinnati Reds) went down to the final out. (See Table 2.) The other outlier is 1927 when Game Four was tied, 3–3, after eight. The Pirates were scoreless in the top of the ninth, and the Yankees won the game and the Series in the bottom of the ninth. This was Murderers’ Row, so how did they win? A walk, a bunt single, a wild pitch, an intentional walk, and a second wild pitch that scored Earle Combs.

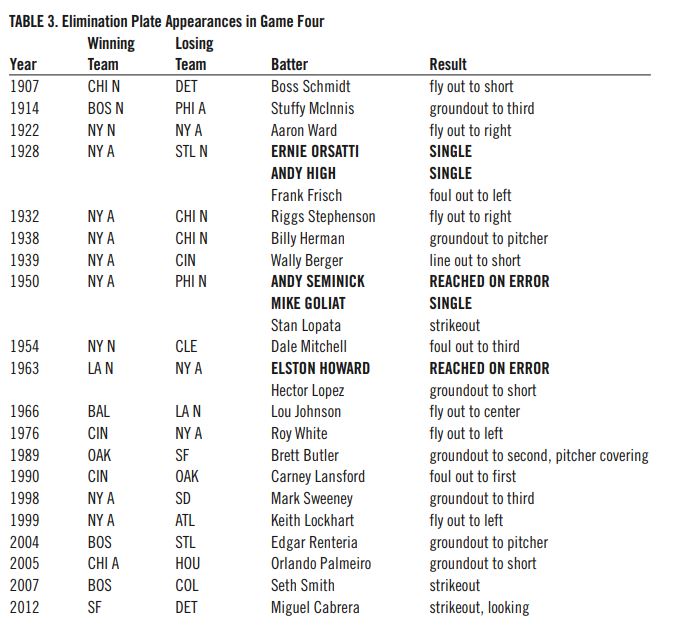

In the other 20 Series that started with three victories for one team, a sweep was the result every time. So in these 20 Game Fours, how many times did a batter facing the prospect of making the last out extend the game for even one more batter? Five times in only three Series. Ernie Orsatti and Andy High both singled for the 1928 Cardinals. Andy Seminick reached on an error, and Mike Goliat singled for the 1950 Philadelphia Phillies. Elston Howard reached on an error for the 1963 Yankees. Five at-bats extended the game, two errors, just three hits.

Every other time, the guy who came up with two out, desperate to keep the game going, made the third out. In all, 25 plate appearances, 25 at-bats, three hits, no walks, three strikeouts, for a batting average of .120. (See Table 3.)

Points of interest. None of these Game Fours ended with a double play and none with a fielder’s choice. Only three ended with a strikeout, 1950, 2007, and 2012. And only one of these ninth innings featured a sacrifice as a way to prolong the game. In 2005, the Chicago White Sox led the Houston Astros, 1–0, going into the ninth inning. Jason Lane singled, Brad Ausmus was out on a sacrifice bunt that moved Lane to second, and the next two batters, both pinch hitters, made out. One may ask if giving up the twenty-fifth out to gain one base was worth it.

Perhaps the most interesting game-ending at-bat occurred in 1963 with Sandy Koufax on the mound for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Bobby Richardson of the Yankees singled. Tom Tresh struck out. Mickey Mantle struck out. Elston Howard hit a ground ball to Maury Wills who flipped to second baseman Dick Tracewski to force Richardson, but Tracewski dropped the ball. Hector Lopez then also grounded to Wills, who this time threw to first to end it.

GAME FIVE

There have been 42 Series that stood at three-games-to-one and thus 42 elimination Game Fives. Eighteen times, the team trailing three-to-one won Game Five and pushed the Series to either six or seven games. But in only one of these 18 Game Fives did the team on the verge of elimination go down to its final out before winning. That happened in 1911. The Giants were down, 3–1, to the Philadelphia Athletics with two out in the ninth. Doc Crandall, a pitcher batting for himself, doubled to score a run, and Josh Devore singled to score Crandall. Devore was then caught stealing. The Giants won the game in the tenth on Fred Merkle’s sacrifice fly, only to lose Game Six the next day, 13–2.

In the other 24 Series that had one team ahead three-games-to-one, that team won Game Five and ended the Series. That gives us 25 Game Fives to look at. But there is one outlier here, too. In 1929, the Athletics led the Cubs, three games to one, but the Cubs led in Game Five, 2–0, going to the bottom of the ninth. Philadelphia scored three times to win the game and the Series.

So again we ask the basic question: how many times in these 24 Game Fives did the batter facing elimination prolong the Series? Eight times in six Series. The year before Crandall and Devore, Jimmy Archer singled. Joe Cronin singled, and Fred Schulte walked in 1933. Gene Hermanski walked in 1949. Carney Lansford singled in 1988, and Placido Polanco walked in 2006.

All in all in these 24 Game Fives, there were 31 plate appearances, 28 at-bats, three walks, five hits. That’s .179. Six Series ended with strikeouts, and there was one game-ending fielder’s choice. (See Table 4.)

Points of interest. Charles (Boss) Schmidt, the Tigers catcher, played in three World Series and made the final out in two of them, 1907 and 1908.

Bill Killefer ended the 1915 Series as a pinch hitter. He grounded to short. It was his only Series at-bat.

The 1949 Series provided the closest parallel to 2012. Duke Snider and Jackie Robinson struck out before Hermanski walked. Gil Hodges then struck out.

GAME SIX

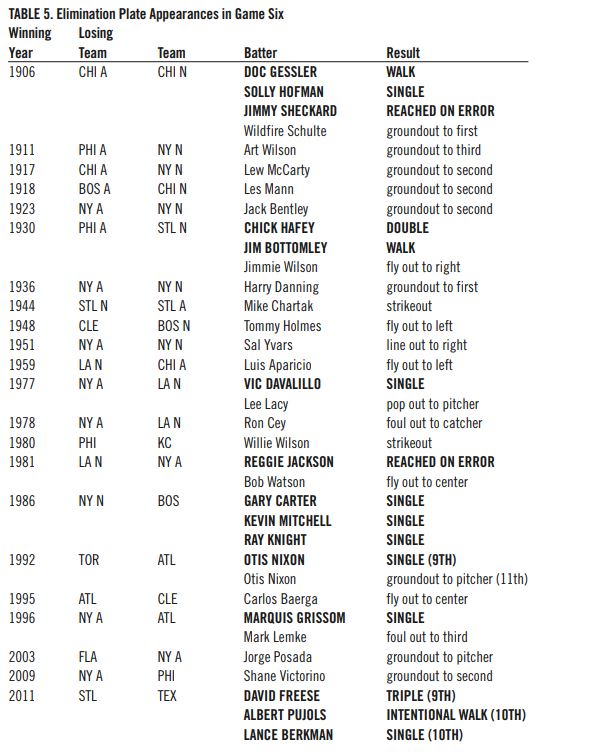

There have been 59 Game Sixes, each of them, of course, an elimination game. Thirty-six have seen the team down three games to two win Game Six, but only twice, in 1986 and 2011, did the team that won go down to its final out.

In the other 23 Series that stood at three games to two, the team with three wins won Game Six and ended the Series. That would give us 25 games to look at. But there are three outliers here. The 1935 Tigers, the 1953 Yankees, and the 1993 Toronto Blue Jays all won Game Six in the bottom of the ninth.

So we have 22 Game Sixes. How many times did the batter keep the Series going? Fifteen times in only eight Series. There were three walks, ten hits, and two batters reaching on errors. Who walked? Besides Pujols in 2011, it was Jim Bottomley in 1930 and pinch-hitter Doc Gessler for the Cubs in 1906. He was followed by Solly Hofman, who singled. Jimmy Sheckard then reached on an error—he was 0-for-21 in the Series—before Wildfire Schulte grounded to first to end it all.

Who got the ten hits? Well, Hofman was one. Carter, Mitchell, and Knight all singled for the ’86 Mets. Freese tripled and Berkman singled in 2011. Besides these, Chick Hafey got a two-out double before Bottomley’s walk in 1930, Vic Davalillo singled in 1977, Otis Nixon singled in 1992, and Marquis Grissom singled in 1996.

In all, these 22 Game Sixes produced 35 plate appearances, 32 at-bats, three walks and 10 hits for a batting average of .313. (See Table 5.)

Points of interest. The weirdest single? It happened in 1977. With runners on first and third and two out, Dodgers pinch hitter Vic Davalillo bunted down the third base line. Graig Nettles of the Yankees came home with the throw, too late to nip Steve Garvey at the plate. Davalillo was credited with single. That made the score 8–4, New York, and then Lee Lacy, also a pinch hitter, popped up a bunt to pitcher Mike Torrez.

The 1992 Atlanta Braves staved off elimination with two out in the bottom of the ninth when Otis Nixon drove in Jeff Blauser to tie the score against Toronto. The Blue Jays scored a pair in the top of the eleventh, but the Braves answered with only one in the bottom of the eleventh, and Nixon made the final out with the tying run on third.

GAME SEVEN

Thirty-six Series have gone the distance. Each one had the potential to create a crucial last at-bat, but six of them did not arrive at this point. Two were decided in the ninth and four were decided in extra innings, all with the home team winning and none with the team in jeopardy reaching its final out.

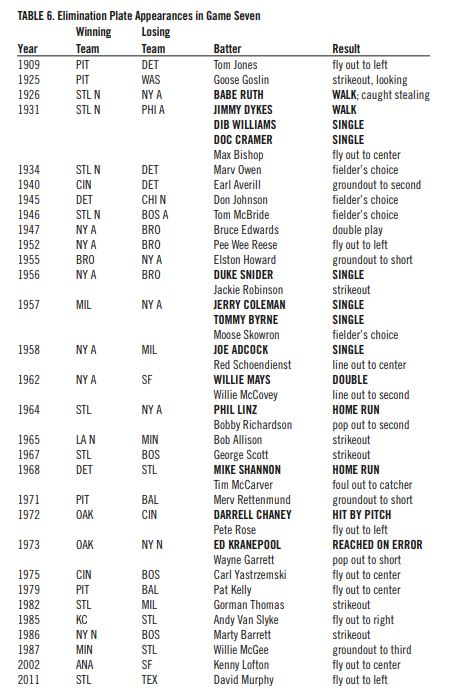

That leaves us with 30 Game Sevens in which a batter on the losing team faced an elimination at-bat. So how many times did these batters succeed? Thirteen times in 10 Series. Nine hits, two walks, one hit batter, and Ed Kranepool reached on an error in 1973.

Who walked? Babe Ruth in 1926 before he was thrown out stealing and Jimmy Dykes in 1931. Darrell Chaney was hit by a pitch in 1972.

Who got the nine hits? There were six singles: Dib Williams and Doc Cramer in 1931, Duke Snider in 1956—before Jackie Robinson struck out in his final at-bat—Jerry Coleman and Tommy Byrne, another pitcher batting for himself, in 1957, and Joe Adcock in 1958. Willie Mays doubled in 1962, and then there were, incredibly, two homers, by Phil Linz in 1964 and Mike Shannon in 1968.

In all, forty-two plate appearances, 39 at-bats, nine hits, six strikeouts, one double play, and four fielder’s choices, all of which ended the game. 9-for-39, that’s .231. (See Table 6.)

Points of interest. The four extra-inning Game Sevens occurred in 1912, the Red Sox over the Giants; 1924, the Washington Nationals over the Giants; 1991, the Minnesota Twins over the Braves; and 1997, the Marlins over the Indians.

The other two games decided in the ninth were played in 1960, the Pirates beating the Yankees, and 2001, Arizona also beating the Yankees.

BEST-OF-NINE

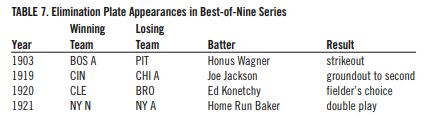

Four Series have been played as best-of-nine: 1903, 1919, 1920, and 1921. There were six elimination games in these Series, but only four games with an elimination at-bat. Four at-bats, one fielder’s choice, one groundout, one double play, and Wagner’s strikeout. Batting average? .000. (See Table 7.)

FINAL THOUGHTS

Since 1903, there have been 108 Series and 167 elimination games. Faced with the chance to make the final out, batters have reached base 42 times, including eight walks and one hit-by-pitch. In 128 at-bats, batters have gotten only 27 hits and have struck out 18 times. But only one batter, for sure, besides Cabrera has been called out on strikes. That was Goose Goslin, Washington, 1925. So Cabrera was not “Beltraned,” as some said at the time, in honor of Adam Wainwright, who struck out Carlos Beltran to end the 2006 National League Championship Series. He was “Goosed.”

STEVEN P. GIETSCHIER has been a SABR member since 1987. He joined the staff of The Sporting News in 1986 to take charge of the company’s archives. He turned a chaotic collection of books, periodicals, photographs, index cards, clippings, and other materials into The Sporting News Research Center and wrote the annual “Year in Review” essay in the Baseball Guide and edited the Complete Baseball Record Book for five years. When TSN moved its editorial offices from St. Louis to Charlotte, North Carolina, in July 2008, the Research Center was dismantled, its holdings boxed up, and its staff discharged. He is now the curator at the Margaret Leggat Butler Library at Lindenwood University.