Bennett Park (Detroit)

This article was written by Scott Ferkovich

Mention the corner of Michigan and Trumbull to baseball fans in the Motor City, and they will immediately think of Tiger Stadium. While it is true that the Detroit Tigers played in that storied park, at that location, from 1912 to 1999, the history of professional baseball at “The Corner” actually dates back to 1896. Back then, Detroit was still largely a city of lumber barons, not automobile magnates. That was the year that the Detroit Tigers, then a minor-league outfit in Ban Johnson’s Western League, opened Bennett Park. The team had previously been known as the Wolverines, but in 1895, manager George Stallings outfitted the team in spiffy new black and yellow striped stockings. Fans and sportswriters alike started referring to the team as the Tigers. Thus, it was only fitting that the following year the team move into new digs to go along with the new nickname.

Mention the corner of Michigan and Trumbull to baseball fans in the Motor City, and they will immediately think of Tiger Stadium. While it is true that the Detroit Tigers played in that storied park, at that location, from 1912 to 1999, the history of professional baseball at “The Corner” actually dates back to 1896. Back then, Detroit was still largely a city of lumber barons, not automobile magnates. That was the year that the Detroit Tigers, then a minor-league outfit in Ban Johnson’s Western League, opened Bennett Park. The team had previously been known as the Wolverines, but in 1895, manager George Stallings outfitted the team in spiffy new black and yellow striped stockings. Fans and sportswriters alike started referring to the team as the Tigers. Thus, it was only fitting that the following year the team move into new digs to go along with the new nickname.

Built at a cost of $10,000 by club owner George Arthur Vanderbeck, Bennett Park was situated in Detroit’s Corktown neighborhood. Originally an Irish enclave of Federal-style homes and row houses, its name was derived from County Cork, where many of its first settlers had come from. The site on which the park was constructed had previously been a combination hay market and dog pound. Before that, it was a public picnic park called Woodbridge Grove, after William Woodbridge, who had once owned a farm at the location. When Vanderbeck began construction, he first had to deal with the nearly thirty giant oak and elm trees that towered over the plot of land. Some of the trees dated back to before the American Revolution. On Cherry Street, beyond where right field would be, was a lumber yard owned by the DeMan brothers. Vanderbeck hired the company to cut down the trees and make them into the lumber that would be used to build his new baseball grounds. For reasons unknown, Vanderbeck decided to spare eight of the trees, several of which stood gracefully in center field, until they were finally felled in 1900.

The park was named after Charlie Bennett, a former catcher for the National League Detroit Wolverines of the 1880s. He has been credited as being the first catcher to don an inside chest protector, and to crouch close behind the batter. Tragically, Bennett had lost both legs while stepping off a train in Wellsville, Kansas. Other names that were suggested for the park were American Beauty, Fairview, Oakdale, Olympia, and Vanderbeck. A couple of the more uninspiring ones were simply Arena and Diamond. With a seating capacity of 5,000, Bennett Park was the smallest in the league.

The first contest played at the new park was an exhibition, on April 13, 1896. The Tigers walloped the Athletics, a local sandlot team, by the score of 30-3. The Detroit Tribune proclaimed that Bennett Park was “vastly superior” to League Park, the Tigers’ former home. The first official game was played on April 28. Charlie Bennett threw out the ceremonial first ball — which he continued to do each Opening Day in Detroit until he died in February 1927. An overflow crowd estimated at 8,000 shoehorned their way into the park. The spectators thoroughly enjoyed the afternoon’s proceedings, as the Tigers defeated the Columbus Senators, 17-2. The first home run at Michigan and Trumbull was hit by Tigers player-manager George Stallings.

The typical parks of this era were hastily constructed, rickety wooden firetraps, and Bennett Park was no exception. It was never really intended to be a permanent facility, and it showed. Bennett Park’s playing surface was inadequate at best, and downright dangerous at worst. This was due to the fact that the former hay market had a cobblestone surface; when the park was built, not enough dirt had been put on top, and as a result the stones sometimes protruded through the grass and dirt, making for a treacherous field. The park’s groundskeepers only raked the field once a week, which certainly didn’t help matters.

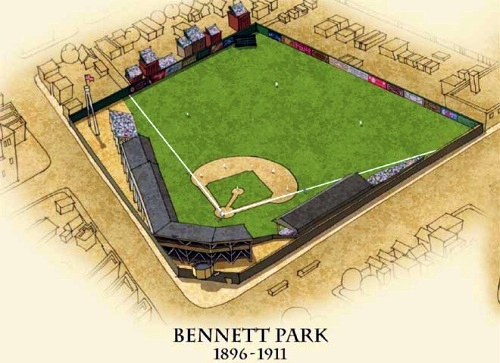

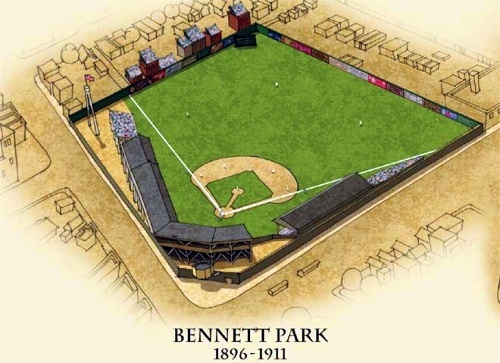

Although situated on the same plot of land as the future Tiger Stadium, the field was positioned differently: Bennett Park’s home plate was actually where right field (the sun field) would be at Tiger Stadium. This caused a problem: The starting time for games was 3:30, which meant the rays from the late-afternoon sun nearly blinded hitters. The park featured an L-shaped wooden grandstand behind home plate and the third base line. The main entrance, along with the ticket booth, was located at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull.

Although situated on the same plot of land as the future Tiger Stadium, the field was positioned differently: Bennett Park’s home plate was actually where right field (the sun field) would be at Tiger Stadium. This caused a problem: The starting time for games was 3:30, which meant the rays from the late-afternoon sun nearly blinded hitters. The park featured an L-shaped wooden grandstand behind home plate and the third base line. The main entrance, along with the ticket booth, was located at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull.

September 24, 1896, was an eventful date in the history of the corner of Michigan and Trumbull. For the first time at that location, a baseball game was played under electric lights. It was club owner Vanderbeck who came up with the idea. He scheduled a doubleheader exhibition against the Cincinnati Reds; the first game was played in the sunshine. Before the start of the second game, hired workers quickly strung up the lights. They were not bright enough to illuminate the field, however, and the experiment quickly fizzled without much fanfare. It would be the last night game played at “The Corner” until the Tigers did it again 52 years later, at Briggs Stadium. One local paper reported that the game was “an amusing and financial success.”

One of the more notable players who wore a Tigers uniform during the club’s minor league days at Bennett Park was George “Rube” Waddell. He holds the Western League record for strikeouts in a single game, with eleven, in a game pitched on May 17, 1898, in Detroit. Waddell later jumped to a league in Canada before going on to have a Hall of Fame career with Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics.

Despite the inadequacies of Bennett Park, Tigers fans mostly supported their team and hungered for a return to major league status. Vanderbeck decided to sell the club on March 6, 1900, to a group of investors headed by James D. Burns, a local saloon owner and former sheriff of Wayne County, which includes Detroit. That same year, Ban Johnson, president of the Western League (of which the Tigers were a member), had assembled a group of club owners to form a separate league, to be known as the American League. Johnson’s ultimate goal was for his new league to become a second major league to compete with the entrenched National League. Initially, Burns was not among the group of owners whom Johnson had selected. Very likely the domineering Johnson viewed the fiery and independent Burns as a threat to his having complete control. Not helping matters for the Tigers was the fact that Detroit’s population at the time was only 296,000, the smallest among potential American League cities. Ultimately, however, Burns and his Tigers were invited to join the new circuit. The team played its first American League game on April 20, 1900. A festive crowd of five thousand fans had little to cheer about, as Buffalo pitcher Doc Amole held the Tigers hitless. The Detroit club went on to finish fourth in the new eight-team American League. It was to be its first and only year as a minor league.

In 1901, Ban Johnson’s heretofore minor-league AL declared itself to be a major league. For the first time in twelve years, Detroit was a major-league baseball town. Bennett Park would need an upgrade, and before the start of the season bleachers were added in right and left field, bringing the park’s capacity to about 8,500, still the smallest in the majors. Regardless of its tiny size, Bennett Park enjoyed the distinction of being one of the American League’s original eight ballparks.

Nevertheless, Opening Day, April 25, 1901, was a time for celebration in the city of Detroit. That day, 10,023 fans were lucky enough to jam their way inside Bennett Park; still others tried to climb over (or crawl under) the wooden fences. The players of both teams, along with a marching band, and thousands of happy citizens, were part of a parade that made its way up Michigan Avenue to the ballpark. Once the game started, however, the Tigers played like they were still a bunch of minor leaguers. Having committed seven errors, they found themselves behind the Milwaukee Brewers 13-4 after eight innings. They battled back to win 14-13, in a comeback for the ages. By season’s end, the Tigers had won 74 games, while losing 61, to finish third. Kid Elberfeld (“The Tabasco Kid”) led the hitting attack with a .308 batting average, while the pitching star was 24-year-old Roscoe Miller, who had the season of his life at 23-13 (he went 16-32 the rest of his career). The team drew 280,184 fans to Bennett Park.

By 1902, it had become increasingly clear that club owner Burns and manager Stallings did not see eye to eye. The bickering mostly involved gate receipts; each man accused the other of secretly pocketing portions of the proceeds. Ban Johnson, tiring of the black mark that the constant war of words was giving his league, decided to take matters into his own hands. He forced both Burns and Stallings out, and handed the reins of the club to Samuel Angus, an insurance agent. Angus brought along his bookkeeper, Frank Navin, who later owned the Tigers for 27 years. By the end of the 1903 season, however, Angus sold his interest in the team to William H. Yawkey, the son of a wealthy lumber baron. (Yawkey’s nephew, Thomas A. Yawkey, would fulfill his own destiny as the longtime owner of the Boston Red Sox.) While all this front-office shuffling was going on, the Tigers struggled both on the field and at the gate. From 1902 to 1904, the team finished no higher than fifth. Attendance fell to 177,796 in 1904, good for next-to-last in the American League in a year in which they lost 90 games. Throughout the rest of the league, doubts swirled as to the viability of small-market Detroit as major league city. In order to increase revenue, Yawkey began selling advertising space on the outfield fences. Stroh’s beer and Bull Durham tobacco were some of the more prominent ads. Batters complained that the colorful ads affected their hitting. During this time of chaos and uncertainty, however, the Tigers landed the player who would define them for the next 22 years.

By 1902, it had become increasingly clear that club owner Burns and manager Stallings did not see eye to eye. The bickering mostly involved gate receipts; each man accused the other of secretly pocketing portions of the proceeds. Ban Johnson, tiring of the black mark that the constant war of words was giving his league, decided to take matters into his own hands. He forced both Burns and Stallings out, and handed the reins of the club to Samuel Angus, an insurance agent. Angus brought along his bookkeeper, Frank Navin, who later owned the Tigers for 27 years. By the end of the 1903 season, however, Angus sold his interest in the team to William H. Yawkey, the son of a wealthy lumber baron. (Yawkey’s nephew, Thomas A. Yawkey, would fulfill his own destiny as the longtime owner of the Boston Red Sox.) While all this front-office shuffling was going on, the Tigers struggled both on the field and at the gate. From 1902 to 1904, the team finished no higher than fifth. Attendance fell to 177,796 in 1904, good for next-to-last in the American League in a year in which they lost 90 games. Throughout the rest of the league, doubts swirled as to the viability of small-market Detroit as major league city. In order to increase revenue, Yawkey began selling advertising space on the outfield fences. Stroh’s beer and Bull Durham tobacco were some of the more prominent ads. Batters complained that the colorful ads affected their hitting. During this time of chaos and uncertainty, however, the Tigers landed the player who would define them for the next 22 years.

On August 30, 1905, a young player just up from Augusta in the Sally League, where he had hit .326, played in his first major-league game for the Detroit Tigers. He batted fifth in the lineup against the New York Highlanders’ Jack Chesbro, a future Hall of Famer who had won 41 games the previous year. About 1,200 people were in the stands at Bennett Park. With a record of 52-60, 15 1/2 games out of first place, the hometown team was simply playing out the string. In the first inning, the young rookie hit a double to left-center field, driving in a run. It was the first of 4,189 hits in his career, a record at the time of his retirement. His name was Ty Cobb. The Tigers still struggled that year, even with the presence of Cobb, who went on to hit .240, the only time in his career he failed to hit .300.

And 1906 was no better. With a 71-78 record and next-to-last again in attendance, at 174,043, the club was in a tailspin. One event worthy of note that year was the longest home run ever hit at Bennett Park. It was a bomb by Sam Crawford on April 29 that sailed over the wall in right field and landed in a yard on the north side of Cherry Street. Club officials estimated that it carried 500 feet.

On the field, the Tigers had reached their nadir, but with young stars like Cobb and Crawford, and pitchers George Mullin and Wild Bill Donovan, Tigers fans could hope for better times at Bennett Park in 1907.

Bennett Park was not without its nuances and charms. Dead center field housed the home team clubhouse. Just like other parks of the time, visitors weren’t provided with facilities. Considering that there was only one showerhead for the entire Tigers team, this may not have exactly constituted a home-field advantage. Laundry facilities were nonexistent; the players merely rolled up their sweaty, smelly woolen uniforms and stored them in metal canisters until the next day’s game. The visiting teams usually stayed at the nearby Cadillac Hotel, where, as was the common practice in those days, they changed into their uniforms, and then were whisked to the park in a horse-drawn trolley. The groundskeeper’s shed was also in dead center. Both the clubhouse and the shed were in play — a mere 490 feet from home plate. The center field scoreboard, which was also in play, featured panels with hand-painted numbers. The operator had to use a ladder to climb up and down the scoreboard in order to hang them up.

At some point, an expansion of Bennett Park included one of its more unusual, if unseen, features: A tunnel was built under the grandstand behind home plate, running to the clubhouse in deepest center field. In the days before the tunnel, a pitcher who had been taken out of the game would have to endure the catcalls of angry fans as he crossed center field to the clubhouse. Now, pitchers could duck into the tunnel for a quick, clandestine getaway.

One noteworthy aspect of Bennett Park was the wildcat bleachers. These towering, tottering and overcrowded wooden stands had been built by property owners just beyond the left field wall along National Avenue (now Kaline Drive). Though the wildcat bleachers were technically not part of the park, their owners nevertheless charged a nickel for seats. More important games brought in the sum of 15 cents. This obviously did not sit well with the Tigers management, who saw the owners of the wildcat bleachers making money off of their product. Using the excuse that the bleachers contributed a rowdy element to the games, team officials decided to hang large strips of canvas atop the outfield fence, thus blocking the view from the wildcat bleachers. Strangely enough, this didn’t stop people from continuing to pay to sit in them. After all, despite the obstructed view, they could still throw rotten vegetables at opposing players. Yawkey and Navin went to court to try to get the bleachers torn down, but to no avail.

For years, Detroit’s strict “blue laws” prohibited baseball from being played on Sundays. To circumvent the issue, club owner Burns had the Tigers play select Sundays at a parcel of land he owned in Springwells Township south of the city but later annexed by Detroit. It was not until 1907 that the first Sunday game was finally played at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull.

The University of Michigan Wolverines football team played three games at Bennett Park. Their first contest at the site was November 4, 1899, as they walloped Virginia by a score of 38-0. On November 10, 1900, they played against Iowa, losing 28-5, before 5,000 fans. Their last game there was November 2, 1901, when they defeated Carlisle 22-0. An estimated 8,000 rooters made their way into the tiny ballpark to watch the contest.

After six years of mediocre baseball, the Tigers won the first of three straight American League pennants in 1907. Led by rookie manager Hughie Jennings, the former Baltimore Orioles star, the Tigers finished 92-58, barely edging Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics. Cobb won his first batting title at .350, while Crawford hit .323. The pitching staff was anchored by Bill Donovan and Ed Killian, both of whom won 25 games. In preparation for Bennett Park’s first World Series, Yawkey built temporary bleachers around the outfield, but to his chagrin they were usually half-empty. The Chicago Cubs rolled over the Tigers in a four-game sweep (plus a Game One tie). On the season, the Tigers drew 297,079. While this was a big improvement over 1906, when only 174,043 passed through the turnstiles, it was still next-to-last in the league. An expansion of Bennett Park after the season resulted in capacity increasing to just over 10,000.

Another tight race in 1908, in which the Tigers prevailed by a half-game over second-place Cleveland, and a game and a half over third-place Chicago, resulted in 436,199 paying customers on the year, a club record. Only Chicago and St. Louis had higher attendance figures. For the Tigers, however, the year ended the same as before, with a World Series loss to the Cubs. The final game of that Series is of historical interest for three reasons. First, only 6,210 fans showed up to Bennett Park for the final Game Five, the lowest attendance for a World Series game before or since. Secondly, the game is the shortest World Series contest ever. Orval Overall mowed down the Tigers by a 2-0 score in a mere 85 minutes. Finally, it would be the last time, to date, in which the Chicago Cubs celebrated a World Series championship.

In 1909, the Tigers again edged the Athletics for the pennant. Ty Cobb won the Triple Crown, leading the American League in batting with a .377 average, home runs with nine, and RBI with 107. No Tiger has won a Triple Crown since. Cobb, already a prolific bunter, was helped by Bennett Park’s grounds crew, which soaked an area in front of home plate to deaden the bunts that he hit. The area became known as Cobb’s Lake. The Tigers set a new club attendance mark at 490,490. They faced off against the Pittsburgh Pirates in the World Series. It was hotly anticipated as a showdown between the two best players in their respective leagues: Ty Cobb and Honus Wagner. The Pirates prevailed in seven games, with Wagner hitting .333 with six RBI, while Cobb could do no better than .231. At only 22 years of age, The Georgia Peach went on to play another 19 years in the majors baseball — 17 with the Tigers — but never again did he play in another World Series. The man with the highest lifetime batting average in baseball, at .367, would finish with an average of .262 in 17 World Series games.

Another offseason expansion at Bennett Park added 3,000 seats. The Park now had three covered grandstands. One was behind the infield; two smaller ones extended down the foul lines. Beyond the right field corner were uncovered bleachers. Altogether, seating capacity was officially listed as 14,000.

After their frustrating World Series losses three years in a row, the Tigers played at Bennett Park for two more seasons. They finished third in 1910, a distant 18 games back, and second in 1911, 13 1/2 games off the pace. By the end of 1911, it was obvious that Bennett Park had outlived its usefulness as a major-league facility. In the previous three years, new concrete and steel parks had been built in Philadelphia (Shibe Park), Pittsburgh (Forbes Field), and Chicago (Comiskey Park). Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis also opened in 1910. The new Polo Grounds debuted in 1911. In the years to come, Cincinnati, Brooklyn, the Boston Red Sox, and the Chicago Cubs would all build new baseball stadiums. Bennett Park, for all its small-town charm, was strictly minor league by comparison. The Tigers played their last game there on September 10, 1911, defeating Cleveland by a score of 2-1. Their final 23 games of the season were on the road.

In its short but colorful history, Bennett Park played host to some very good baseball, along with three World Series. In addition to Tigers greats such as Cobb and Crawford, the list of legends who played at the park reads like a “Who’s Who in Deadball History”: Cy Young, Honus Wagner, Shoeless Joe Jackson, Eddie Collins, Tris Speaker, Ed Walsh, Smokey Joe Wood, Jack Chesbro and Nap Lajoie, to name a few. Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack waved his scorecard from Bennett Park’s visitor’s bench on many an occasion. Even a young John McGraw managed a few games there when he was the visiting skipper for the Baltimore Orioles in their early American League years. By the end of the 1911 season, however, Frank Navin, by now the principal owner of the Tigers, would tear down the rickety wooden park, build a new, bigger baseball palace on the same site, and name it after himself. Navin Field eventually became Briggs Stadium, which in turn became Tiger Stadium, and the Tigers continued to play at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull until the end of the century. But it was Bennett Park that started it all.

Sources

Charles C. Alexander, Ty Cobb (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1984), 31-34.

Richard Bak, A Place for Summer: A Narrative History of Tiger Stadium (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1998), 55, 57-58, 62, 75, 97.

Michael Benson, Ballparks of North America: A Comprehensive Historical Reference to Baseball Grounds, Yards and Stadiums, 1845 to Present (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company), 134-136.

Michael Betzold and Ethan Casey, Queen of Diamonds: The Tiger Stadium Story (West Bloomfield, Michigan: A&M Publishing Co., Inc., 1992), 29-38.

Michael Gershman, Diamonds: The Evolution of the Ballpark (Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1993), 66-67.

Jim Hawkins and Dan Ewald, The Detroit Tigers Encyclopedia (Sports Publishing L.L.C., 2003), 5, 33-35.

Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Walker & Company), 82-83.

John McCollister, The Tigers and Their Den (Lenexa, KS: Addax Publishing Group, 1999), 22-48.

Bill McGraw, “Falling Stadium Lights Have History,” Detroit Free Press, http://www.freep.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20080722/COL27/80722064, accessed July 27, 2012.

“Past Detroit Tigers Venues,” mlb.com, http://detroit.tigers.mlb.com/det/ballpark/information/index.jsp?content=pastvenues, accessed July 27, 2012.

Baseball-Reference.com

Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan Athletics History, http://bentley.umich.edu/athdept/football/football.htm, accessed July 27, 2012.

Photos

1. An artist’s rendering of Bennett Park (Courtesy of Detroit Athletic Company Blog, http://blog.detroitathletic.com/2008/04/29/buried-treasure-at-the-corner/, accessed August 2, 2012).

2. Bennett Park looking from left field toward home plate, 1906 (Courtesy of Library of Congress, http://rs6.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?cdn:1:./temp/~ammem_AHcp::, accessed August 2, 2012).

3. Davy Jones batting on Opening Day, 1911, during a snowstorm at Bennett Park (Courtesy of Detroit News, http://multimedia.detnews.com/pix/photogalleries/newsgallery/OpeningDay/index.htm, accessed August 2, 2012).