Manhattan Field (New York)

This article was written by Bill Lamb

For about a decade near the turn of the last century, now forgotten Manhattan Field served as an important New York sports venue. Hastily erected in 1889 to accommodate a displaced New York Giants franchise and initially called the New Polo Grounds, the park was an early success, hosting good regular season crowds plus that season’s inter-league championship match, won by the Giants in nine games. But its time as a major-league playing site was brief. Within two years, the ballpark lost both its team and its title, supplanted as Giants home base by an adjoining edifice that assumed the name Polo Grounds as well. For the remainder of the 1890s, the abandoned park, renamed Manhattan Field, catered to other activities, most prominently big-time college football, flying wedge style. Sadly, this too would not last long. Rather quickly, Manhattan Field fell into disuse, and within 20 years of its construction, the ballpark was reduced to little more than the vacant ground that it had once been.

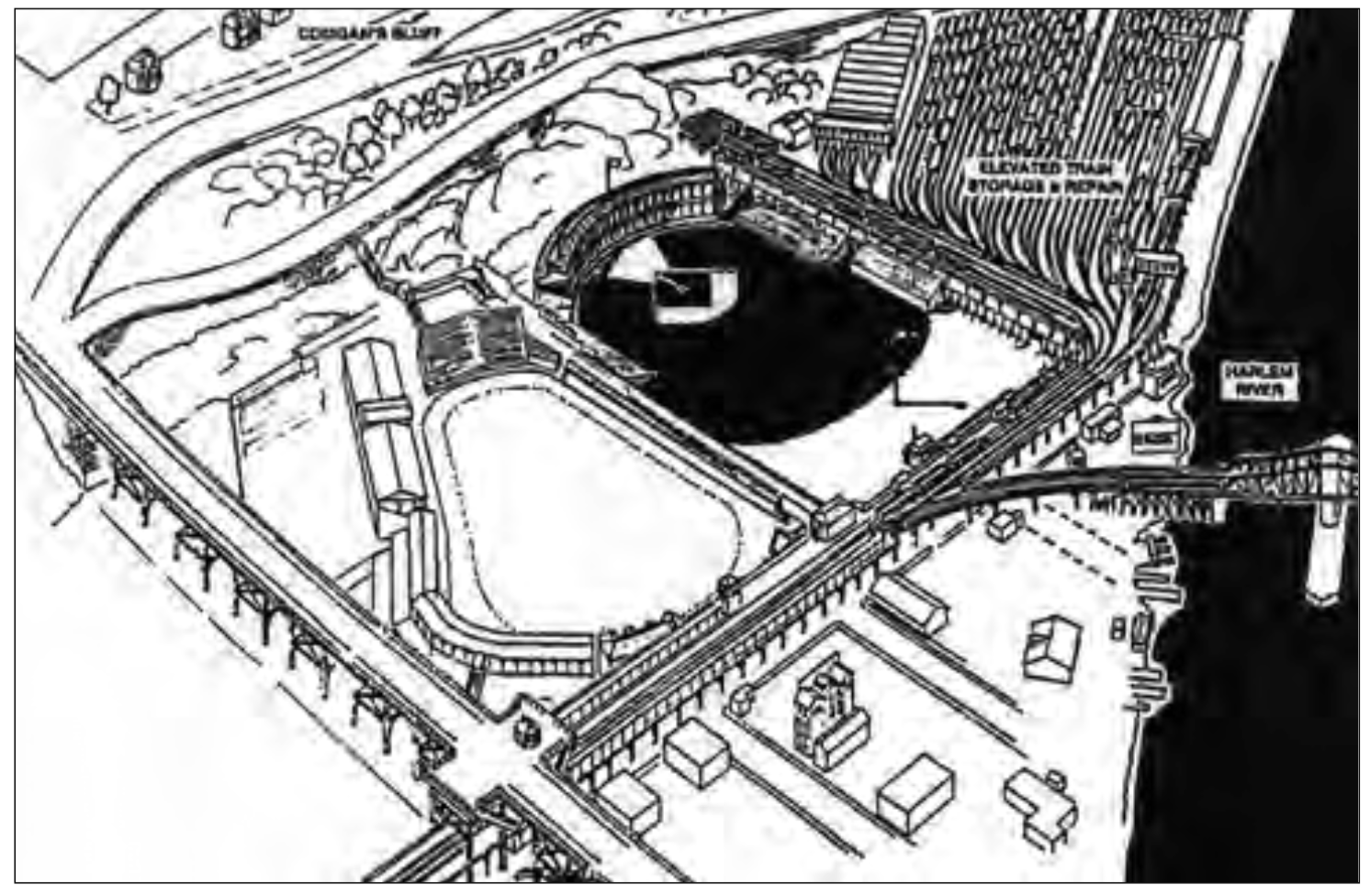

The site of this lost ballpark was reclaimed meadowland situated at the far north of Manhattan Island, hard by the Harlem River and dominated by a 175-foot-high palisades that came to be known as Coogan’s Bluff. During the 1880s, the hollow beneath the bluff was used for baseball and other amusements and informally acquired the name Manhattan Park or Manhattan Field.1 Tolerating such public use of the property was the Gardiner family, New York grandees who traced their ownership of this and other tracts of north Manhattan real estate back to the reign of Stuart kings.2 In 1889, major league baseball came to the area through the intersection of death and politics. Since late in the 1880 season, the New York professional team, first as an independent organization and thereafter as the National League New York Giants, had utilized a ballpark erected on a former polo field in mid-Manhattan, just north of Central Park. Naturally enough, this ballpark took on the name Polo Grounds.3 At the conclusion of the 1888 season, the Polo Grounds Giants were baseball’s champions, having defeated the St. Louis Browns of the American Association in the October clash of league pennant winners. But as the 1889 season approached, city planners, temporarily immune to the Tammany connections of team owner John B. Day, put into motion longstanding plans to complete the local traffic grid by running a street through the Giants playing field. In desperate need of grounds for a new ballpark, Day cast his eyes northward and settled upon a grassy tract located at 155th Street and 8th Avenue — the locus of Manhattan Field.

Although in sparsely populated territory far removed from midtown, the grounds were flat, vacant and, most important, serviced by a stop on the New York and Northern elevated railway. Happily for Day, the grounds were also available, among the assets put up for sale by the heirs of the recently deceased William L. Lynch.4 In short order, the Giants owner entered into negotiations with James J. Coogan, son-in-law of the widowed Sarah Gardiner Lynch and executor of the Lynch estate.5 Day, however, could not meet the property’s asking price. Nor would he enter the one-year rental agreement proffered by Coogan, as the cost to be incurred from the construction of a new stadium could not be risked upon so short a lease. As baseball’s opening day loomed, Day’s plight was publicized in an extraordinary advertisement published in the New York dailies. It read:

I want to find a party to purchase from the present owners, who will not lease, the plot of ground bounded by 8th and 9th Aves., 155th to 157th Sts., which I will lease for five to ten years, at a rental of $6,000 per year. JOHN B. DAY, President, New York Baseball Club, 121 Maiden Lane.6

When the needed angel did not materialize, Day’s Giants were obliged to open the season at Oakdale Park in Jersey City. After two games there, the team relocated to the St. George Cricket Grounds on Staten Island, erstwhile home to the New York Metropolitans of the rival American Association. But wet weather and the inconvenient locale of the grounds decimated attendance at Giants games. Quickly, it became clear to Day that playing outside of the city was a losing proposition. But by now, fortuitously, Coogan had relaxed his position on rental of the north Manhattan site. On June 22, 1889, it was revealed that the Lynch estate and Giants management had reached agreement on a five-year leasehold.7 But in a move that he would come to regret, Day leased only so much land as he needed for his new ballpark, declining an offer to rent the hollow property in its entirety.

As soon as the lease was signed, work on the construction of the new Giants ballpark commenced at a furious pace.8 With material salvaged from the original Polo Grounds, Day enlisted a small army of workmen who produced a usable, if unfinished, ballpark within a remarkable three weeks.9 The playing field was laid out somewhat oddly—like a pear laying on its side; at 360 feet, the fence in dead center field was actually closer to home plate than the left and right field corners. It also featured a steep incline fronting the outfield fence from center to right. Still, the enclosure, christened the New Polo Grounds, was a handsome, well-built ballpark. When completed over the winter of 1889-1890, the New Polo Grounds featured a covered two-tier grandstand behind home plate, with a large clubhouse to the right and a covered grandstand (with horse stables beneath) extending down the entire left field line. An open bleachers section sat behind the left field fence.10 In all, the seating capacity of the park exceeded 14,000.11 Unfortunately for management, the topography of the surrounding area also afforded view of field action for non-paying fans. Spectators standing above the hollow on the 8th Avenue Viaduct, the Harlem Speedway, or the stairway of the elevated train had an excellent vantage point for games played upon the New Polo Grounds, while more distant views were available to those standing atop a stretch of the palisades soon dubbed Dead Head Hill.12

On July 8, 1889, the Giants opened the still uncompleted ballpark to a paying crowd of over 10,000. An estimated 5,000 more observed game action from perches outside the grounds.13 To the satisfaction of the faithful, Cannonball Crane pitched just well enough to secure a 7-5 Giants victory over Pittsburgh. That triumph foreshadowed the team’s winning ways at the New Polo Grounds. Their wandering start notwithstanding, the Giants played well for the remainder of the season and nipped the Boston Beaneaters at the wire for the 1889 NL pennant. The Giants then successfully defended their title, defeating the AA Brooklyn Bridegrooms in the championship match, six games to three.

As Day surveyed the horizon in the fall of 1889, he had ample reason to be content. Despite the ballpark problems of the early season, the Giants had managed a profit for the year, a matter which prompted Day to decline a $200,000 offer for the franchise from James J. Coogan.14 In Day’s view, the Giants were worth far more than that, particularly with the team’s venue issue resolved; the Giants were now secure tenants of a handsome new stadium that promised to attract good crowds.15 Those crowds, and the continuing profits that would come with them, seemed guaranteed, as Day’s two-time world champion team was stocked with Hall of Fame-caliber players in their prime: Buck Ewing, John Montgomery Ward, Tim Keefe, Roger Connor, Jim O’Rourke and Mickey Welch. But trouble, in the form of the Giants’ star shortstop and the team’s mercenary landlord, was near at hand.

Seizing upon player resentment of the reserve clause and a recently enacted salary classification plan, the dynamic, well-educated Ward organized, almost singlehandedly, a rival major league baseball circuit, the Players League. Ward and his agents then induced virtually all the NL’s stars to jump to the new league, with the Giants particularly hard hit by player defections.16 Worse yet for Day, his new competition in New York would be playing their games directly next door, the Players League having obtained use of the vacant north end of the hollow from Giants landlord Coogan. Despite his relationship with the Giants, Coogan had had no qualms about leasing immediately adjacent grounds to Edward B. Talcott and other well-heeled Republican businessmen-politicians bankrolling the New York Players League team. When the 1890 season opened, the Players League Giants were playing in newly constructed Brotherhood Park, a 16,000-seat stadium separated from Day’s New Polo Grounds by no more than outfield fences and a ten-foot-wide alley.17

The fan allegiance question was settled early. The Ewing-led PL Giants drew 12,013 for their 1890 season opener in Brotherhood Park, while only 4,644 watched Day’s depleted National Leaguers in the adjoining ballpark. That roughly three-to-one fan ratio would continue throughout the season, but both teams drew poorly.18 Typical were the numbers in attendance for competing games played on May 12. Only 1,707 fans paid their way into Brotherhood Park to see the Players League New York-Boston game while a lonesome 687 souls attended the National League New York-Boston contest across the alley in the New Polo Grounds. But as word of a fierce pitching duel between the Beaneaters Kid Nichols and the Giants Amos Rusie made its way over the divide, the Brotherhood Park contingent abandoned the Players League game, heading for the top of the right field bleachers to spy on the exhibition next door. New York fans of both stripes were ultimately gratified when league loyalist Mike Tiernan broke up a scoreless game with a 13th inning home run, a clout that reportedly cleared the New Polo Grounds, crossed the alley, and struck the outside fence of Brotherhood Park.19

The 1890 season was financially ruinous for Day. Only the furtive infusion of cash by other National League team owners saved the New York franchise from bankruptcy that season.20 By closing day, John B. Day’s stewardship of the Giants was near its end. For a time thereafter, he would remain as figurehead president of a consolidated New York NL/PL franchise, a union of necessity forged while the Players League was in its death throes. But real executive power in this new arrangement would be wielded by Talcott and his allies, now in control of the majority of Giants stock.21 This development, in turn, precipitated the demise of the New Polo Grounds as a venue for major league baseball. The choice of Brotherhood Park as the 1891 Giants home over the New Polo Grounds was not necessarily based on the merits of the two ballparks. Here, the New Polo Grounds—comparable in seating capacity, more spacious in the outfield corners, and, arguably, more pleasing to the eye—seemingly held the edge. But its rival held the trump card: Brotherhood Park was the home field of the Talcott forces, now dominant in the Giants front office. Perhaps more to the point, Talcott himself had signed a ten-year lease on Brotherhood Park in 189022, and he had no intention of being stuck with an idle ballpark. Thus, Brotherhood Park would receive the surviving Giants team and would also adopt the name of the Polo Grounds.

During its fleeting tenure as the New Polo Grounds, the forsaken ballpark had hosted the 1889 world championship series and 112 major league baseball games — 104 as home field of the NL New York Giants and eight for the 1890 AA Brooklyn Gladiators, a vagabond operation that took refuge in the New Polo Grounds after being evicted from Ridgewood Park in Queens.23 With lessons learned from the 1890 season, present and future Giants owners would never again permit a major league baseball game to be played at the lower hollow ballpark (although pre-season Giants workouts would occasionally be conducted on the team’s old grounds). However, things did not remain dormant at the former New Polo Grounds. During 1891, its playing field was used by the city’s various athletic organizations, particularly the Manhattan Athletic Club. Sometime early that year, the lease for the premises had been acquired by the MAC, a roost for affluent young men with sporting inclinations. The club fielded more than a dozen teams, including squads for baseball, football and track. To distinguish the Manhattan Athletic Club grounds from the adjoining stadium of the Giants, the name Manhattan Field was revived.24 A full complement of MAC baseball games was played at Manhattan Field during Spring/Summer 1891. The MAC also hosted a handful of club football games played there in the fall. But the real lifeblood of Manhattan Field (and a substantial rental moneymaker for the MAC) was the scheduling of college football, just now bursting upon the scene as a popular attraction. On November 14, 1891, an estimated crowd of 5,000 was in attendance at Manhattan Field for Yale’s 48-0 pummeling of Penn. But that gathering paled besides the 40,000 throng present in and around Manhattan Field for the 1891 Thanksgiving Day game between Yale and Princeton, won convincingly by the Eli 19-0.25

Manhattan Athletic Club sporting events continued to occupy Manhattan Field in early 1892 while the Yale, Princeton, Penn, Cornell and Wesleyan college elevens graced its gridiron that fall. Late that year, however, the MAC found itself in serious financial straits. An ensuing club petition for protection from its creditors led to a fateful event in the history of Manhattan Field and, derivatively, the New York Giants, the appointment of Andrew Freedman as receiver of MAC affairs in January 1893.26 With an appraised value of $20,000 per year, the lease to Manhattan Field was a valuable MAC asset, so receiver Freedman had frequent occasion to be on the premises and, in short order, he developed an interest in the next-door neighbors, the New York Giants—a team that he would soon come to own. Freedman, a real estate millionaire and Tammany Hall insider, is invariably cast as a villain in baseball annals. An abrasive man with a hair-trigger temper and a pronounced vindictive streak, Freedman was often a difficult character to contend with. But he was also a man of formidable abilities, not the least of which was business acumen.27 Among the measures swiftly employed by Freedman to maximize distressed MAC revenues was expanded use of Manhattan Field. In due course, the roster of grounds activities would be enlarged to include horse shows, harness racing, cricket, track and field meets, Gaelic football, and bicycle races. Manhattan Field even became the site of a balloon launch.28 As in years past, though, the annual Manhattan Field highlight was the Thanksgiving Day football game between Yale and Princeton. In 1893, the Tigers prevailed 6-0 before approximately 50,000 spectators, including a horde atop Dead Head Hill which an enterprising James J. Coogan had cordoned off for fans whom he charged fifty cents, well under the $2 Manhattan Field admission fee.29

Much to Freedman’s chagrin, constructing screens and re-orienting the Manhattan Field gridiron did little to obstruct the view of non-paying spectators standing on the viaduct, the speedway, the railway stairs, or the nearby palisades. But when an estimated 20,000 freeloaders enjoyed the 1896 Yale-Princeton game from outside the grounds, Freedman had had enough. From that point on, college football dates would be transferred to Polo Grounds III (Brotherhood Park), a venue with far less commodious sightlines from the outside than Manhattan Field.30 For the next two years, little publicly reported activity took place at Manhattan Field. But in 1899, Freedman sublet the grounds to the fledgling Columbia University football program, and soon decent crowds returned to Manhattan Field, now sometimes called Columbia Field.31 This, however, would prove the last gasp for major sports at the facility. Columbia discontinued use of Manhattan Field after the 1901 season, when the student-managed football program defaulted on the $15,000 rent due Freedman and had to be bailed out by the university administration.32 The Columbia team thereupon found different accommodations, no great loss to Freedman who had made little profit on the arrangement with Columbia. The field sublet only covered Freedman’s lease of Manhattan Field from the Gardiner-Lynch family33, but control of Manhattan Field had served other purposes for Freedman.

During a bruising two-year (1898-1900) conflict with fellow National League team owners, Freedman brandished Manhattan Field like a blackjack, threatening to make it available to league rivals if he did not get his way on syndicated team ownership, NL contraction to an eight-club circuit, and other contentious policy matters. In their ultimate capitulation to the wealthy and ruthless Freedman, the magnates agreed, among other things, to reimburse the Giants owner for the annual cost of the Manhattan Field lease.34 That sealed the fate of Manhattan Field as a baseball venue. Although the outlines of its diamond were still visible in a 1901 panoramic photo of the grounds, Manhattan Field would be left fallow from then on, strategically withheld from use by the league. Any prospects for a renaissance, moreover, were obliterated in September 1902 when Freedman sold the Giants to John T. Brush, formerly principal owner of the Cincinnati Reds and long a Giants minority stockholder. Although franchise assets acquired by Brush included the long-term Manhattan Field lease, the new owner had scant interest in the property—aside from keeping it out of American League hands. Under the new Giants regime, Manhattan Field was to be neglected, slowly dismantled over time for Polo Grounds III spare parts.

In September 1904, plans to convert the Manhattan Field site into a Coney Island-style amusement park were announced.35 But nothing ever came of it. In the years following, the name Manhattan Field was occasionally in newsprint as the scene of an airship hangar or circus grounds.36 But the depths to which Manhattan Field had sunk would not become fully apparent until a fire almost totally destroyed Polo Grounds III in April 1911. Notwithstanding the remnants of a once proud ballpark immediately adjacent to the Polo Grounds reconstruction site, John T. Brush did not give rehabilitation of Manhattan Field a moment’s thought. Rather, Brush preferred to swallow his pride and accept the offer of temporary use of cramped Hilltop Park from his AL competitors. While the iconic Polo Ground IV was under construction, James J. Coogan grandly announced that Manhattan Field would soon be transformed into an amphitheater/stadium with amusement park to be known as Olympia, its $6 million construction cost to be underwritten entirely by Coogan’s wife.37 But this was another pipe dream. By 1919, when a mammoth Babe Ruth home run soared beyond the confines of the Polo Grounds onto Manhattan Field, the landing spot was described as a weed-filled vacant lot.38 Some years thereafter, that lot would be paved over, the Manhattan Field site becoming a parking lot for those driving to the Polo Grounds or nearby Yankee Stadium.39

In the 1960s, the city acquired the Polo Grounds/Manhattan Field tract through eminent domain and, following demolition of the last New York Giants ballpark, converted the area into a high-rise public housing project.40 Named Polo Grounds Towers, the site offered, at least, a bow to history. But no such reminder of the other sporting edifice that once adorned the grounds was planted on scene, finalizing the fate of Manhattan Field as New York’s forgotten ballpark.

Notes

1 See e.g., the New York Times, June 24, 1886, reporting on a baseball game played by two company teams on the grounds of “Manhattan Park.”

2 Patriarch of the clan was Lion, Lord Gardiner, the seventeenth-century settler-soldier for whom New York’s exclusive Gardiner’s Island is named. In addition to vast tracts in north Manhattan, Gardiner’s descendents owned commercial property in lower Manhattan and various estates on Long Island.

3 For more expansive consideration of the original Giants home field and its successors, see Stew Thornley, New York’s Polo Grounds: Land of the Giants, Temple Univ. Press, Philadelphia, 2000. The writer is indebted to Stew Thornley for his prompt and generous response to inquiries about Manhattan Field, aka the New Polo Grounds.

4 The 105 northern Manhattan lots available for purchase from the Lynch estate were mentioned in the New York Times, February 22, 1889.

5 The son of Irish immigrants, James Jay Coogan (1845-1915) had risen from humble station as an upholsterer to co-proprietor of Coogan Brothers, a prosperous Bowery furniture business. But real upward mobility came in 1885 when Coogan married money, taking as his bride Harriet Gardiner Lynch, heiress presumptive to the family holdings in north Manhattan and elsewhere. Coogan’s access to the Gardiner-Lynch fortune financed quixotic bids for the New York mayoralty in 1886 and 1888, when he finished a distant fourth as candidate of the United Labor Party. By 1889, Coogan was temporarily removed from politics, dividing his time between the furniture business and managing the estate of his late father-in-law, the realtor William L. Lynch.

6 As re-published in the New York Times, April 8, 1889, which noted that “the property referred to is a portion of the Lynch estate controlled by James J. Coogan” and that a long term lease could not be acquired because “the estate desires to sell this and the adjoining property.” Thus, Day was hoping for the intervention of “some capitalist … (to) purchase the two blocks of land … and give the (Giants) management a five or ten year lease.”

7 As reported in the New York Tribune/New York Times, June 22, 1889, and elsewhere.

8 To maintain continuity of brand and to avoid confusion, this new ballpark would retain the Polo Grounds name of its predecessor. In subsequent years, the proprietors of Madison Square Garden would follow Day’s example when relocating the arena away from its original site on Madison Square.

9 Work had been interrupted briefly by the appearance of a rival construction crew engaged by Cleveland street car mogul and would-be baseball team owner Albert Johnson. The Day forces summoned Coogan who quickly put the interlopers off the property, as reported in the New York Times, June 25, 1889.

10 Informative drawings and a superb photo of the ballpark layout can be found at Thornley, pp. 31-35.

11 A crowd of 14,364 is reported to have attended a September 1889 game at the New Polo Grounds, as per http://www.seamheads.com/ballparks.php?parkID=NCY09.

12 The appellation Coogan’s Bluff, the more enduring name for this location, was not coined until around 1893.

13 New York Times, July 9, 1889.

14 New York Times, September 6, 1889.

15 A five year lease option was formally reached between Day and the Lynch estate the following Spring. See the New York Times, March 2, 1890.

16 Among those signed by the New York entry in the Players League were future Hall of Famers Ewing, Keefe, Connor and O’Rourke, as well as 1889 Giants regulars George Gore, Danny Richardson, Art Whitney, Mike Slattery and Hank O’Day, the unlikely pitching star of the 1889 World Series. Ward himself assumed field command of the Players League team in neighboring Brooklyn.

17 The extraordinary proximity of the two ballparks can be visualized in photos at Thornley, pp. 34-35, and http://www.baseball-fever.com/showthread.php?84493-Manhattan-F… This phenomenon, however, was not without precedent. During the 1883 season, the NL Giants and AA New York Metropolitans had occasionally played on abutting diamonds at the original Polo Grounds.

18 During the 1890 season, the PL Giants drew 148,197 fans to Brotherhood Park while 60,667 attended NL Giants games at the New Polo Grounds, both totals mere fractions of the 305,455 attendance figure posted by the Giants at the original Polo Grounds in 1888, as per http://www. baseballchronology.com/Baseball/Teams/Background/Attendance.

19 As reported in the New York Press, May 13, 1890, New York Times, May 13, 1890, and elsewhere.

20 To avert collapse of the NL’s flagship New York franchise, Chicago White Stockings owner Albert Spalding orchestrated a financial bailout. In addition to Spalding’s contribution, Day’s operation was kept afloat by cash from team owners Arthur Soden (Boston), John T. Brush (Indianapolis), Al Reach (Philadelphia), and Ferdinand Abell (Brooklyn). See Seymour, H. (and Mills, D.), Baseball: The Early Years, Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 1960, p. 238.

21 For an illuminating account of the franchise’s executive struggles, see James Hardy, The New York Giants Base Ball Club, 1870 to 1900, McFarland & Co., Jefferson, NC, 1996, pp. 120-141.

22 As noted in the Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1890, and the Boston Globe, May 27, 1890. Talcott’s responsibility for the Brotherhood Park lease was also mentioned in his obituary in The Sporting News, April 17, 1941.

23 The Gladiators came into existence after the Brooklyn Bridegrooms, AA champs of 1889, switched to the NL for the 1890 season. A collection of nonentities, the Gladiators inhabited the AA cellar until the team disbanded in late August.

24 This, at least, is the commonly accepted etymology of the name Manhattan Field. See e.g., Thornley, p. 48: “The New Polo Grounds … reverted to its previous name, Manhattan Field.” The writer, however, is not entirely persuaded, as pre-1889 references to the grounds as Manhattan Field are sparse, at most. It is not implausible that the title Manhattan Field was derived from use of the field by the Manhattan Athletic Club, as evidenced by the interesting progression in terminology employed by the New York Times in publicizing MAC baseball games. Such contests went from being played at “Manhattan Athletic Club grounds” (New York Times, March 28, 1891) to “on the Manhattan field” (New York Times, April 2, 1891) to “at Manhattan Field,” New York Times, May 28, 1891.

25 A thorough accounting of the football games played at Manhattan Field can be accessed on-line via http://www.luckyshow.org/football/mf.htm. An instructive diagram depicting how the grounds were arranged for football is also available on the site. Expanded seating capacity for Manhattan Field football was achieved by enlargement of the old left field bleacher section and by the use of temporary stands. Football attendance figures, however, may also have incorporated the numerous freeloaders who watched the games from perches outside the stadium walls, as reflected in reportage of the 1892 Yale-Princeton game by the New York Times, November 26, 1892.

26 New York Times, January 29, 1893.

27 From his appointment as receiver of the Manhattan Athletic Club through his late life management of the affairs of deranged socialite Ida Flagler, Freedman was respected for his capable and scrupulous, if usually pricey, administration of estates, trusts and other judicial referrals. Friendly with various club members, Freedman performed his duties as Manhattan Athletic Club receiver free of charge, as reported in the New York Times, July 7, 1893.

28 The liftoff of intrepid French aeronaut Emil Carten drew an assemblage of 400 paying customers seated inside Manhattan Field and some 5,000 gawkers atop Dead Head Hill, as per the New York Times, July 13, 1893.

29 The Times account of the matter provided perhaps the first prominent newsprint identification of the palisades as Coogan’s Bluff. At the time, Coogan was in need of the $3,000 or so pocketed from this venture. His furniture business was failing and Coogan would soon be headed to bankruptcy court. In subsequently filed pleadings, Coogan averred that he was “entirely penniless and … dependent for shelter on his mother-in-law,” as quoted in the New York Times, January 1, 1894. For the remainder of his days, Coogan lived comfortably off Gardiner-Lynch family largesse and Tammany patronage, Wigwam boss Richard Croker arranging Coogan’s appointment as Manhattan Borough president in 1899.

30 In January 1895, Freedman had acquired majority control of the Giants franchise by buying out Talcott and his faction. Control of the north Manhattan sporting scene came with the transaction, as long term renewable leases for both the Polo Grounds and Manhattan Field were included assets of the Giants franchise. Title to the property on which the Polo Grounds and Manhattan Field stood, however, remained with those in the Gardiner line.

31 Crowds estimated at 25,000 were on hand to see the Lions play Cornell and the Carlisle Indian School in 1899, and some 36,000 attended the November 24, 1900 clash between Columbia and Carlisle, with the home team a 17-6 victor.

32 New York Times, January 4, 1902.

33 The $15,000 that Freedman paid the Lynch estate annually for the Manhattan Field leasehold was less than the $10,000 rent that the Polo Grounds III lease cost him each year, as per the minutes of the December 10, 1901 NL Board of Directors meeting, contained in the Manhattan Field file, Giamatti Research Center, Cooperstown.

34 For more on Freedman’s clash with fellow team owners, see William F. Lamb, “A Fearsome Collaboration: The Alliance of Andrew Freedman and John T. Brush,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, Vol. 3, No. 2, Fall 2009, pp. 10-12.

35 See the New York Times, September 25, 1904, and the Hartford Courant, October 3, 1904.

36 See e.g., the New York Times, July 22, 1906, and June 11, 1910.

37 In an effort to shield her daughter’s inheritance from the intra-family litigation that the Gardiner clan had a penchant for, Sarah Gardiner Lynch had transferred title to assorted properties, including the Polo Grounds/Manhattan Field tract, to Coogan’s wife in 1898. Although James J. would continue to serve as family estate agent and public spokesman thereafter, decisions about the use of Gardiner-Lynch property were made entirely by the tough minded but intensely private Harriet Lynch Coogan.

38 New York Times, September 25, 1919.

39 Yankee Stadium was only a short walk across the Macombs Dam Bridge from the Polo Grounds and those driving to Yankees games regularly parked there.

40 The condemnation process was bitterly resisted by the Gardiner descendents and litigated up to New York’s highest court, where the city again prevailed. The children of Harriet Coogan eventually received $4.34 million for their loss. See the New York Times, November 17, 1964.