Athletic Park (Minneapolis)

This article was written by Stew Thornley

A number of sites and facilities, usually short-lived, were used for baseball in Minneapolis in the 19th century. In 1876, the Blue Stockings had a ballpark on Eighth Street in south Minneapolis. Reports in the Minneapolis Tribune varied from day to day as to the exact location of the grounds on Eighth Street. The July 18, 1876 Tribune put the enclosure between 16th and 17th avenues. However, the description in the next day’s Saint Paul and Minneapolis Pioneer Press put the ball park at the “Eighth Street corner of Twentieth Avenue South” and noted, “The grounds are 500 feet long by 475 feet wide, surrounded by a high board fence. The commodious amphitheatre, roofed in thus warding off the sun, will accommodate comfortably 900 people.” The St. Paul Dispatch added, “The field is almost as level as a floor, and the diamond perfection itself.”

A number of sites and facilities, usually short-lived, were used for baseball in Minneapolis in the 19th century. In 1876, the Blue Stockings had a ballpark on Eighth Street in south Minneapolis. Reports in the Minneapolis Tribune varied from day to day as to the exact location of the grounds on Eighth Street. The July 18, 1876 Tribune put the enclosure between 16th and 17th avenues. However, the description in the next day’s Saint Paul and Minneapolis Pioneer Press put the ball park at the “Eighth Street corner of Twentieth Avenue South” and noted, “The grounds are 500 feet long by 475 feet wide, surrounded by a high board fence. The commodious amphitheatre, roofed in thus warding off the sun, will accommodate comfortably 900 people.” The St. Paul Dispatch added, “The field is almost as level as a floor, and the diamond perfection itself.”

The 1883 ball park of the Minneapolis Browns was at the corner of Nicollet Avenue and Lake Street, essentially the same tract that Nicollet Park occupied from 1896 to 1955. However, the 1883 ball park had frontage on Lake Street, which wasn’t the case with Nicollet Park. A Minneapolis atlas from the mid-1880s shows the parcel on the southwest corner of Lake and Nicollet, covering the entire block between Nicollet and Blaisdell avenues and Lake and 31st streets, as owned by H. M. Carpenter. This 10-acre lot extends south, across 31st Street, for another half-block, with this portion eventually becoming the site of the car barns for the Twin City Rapid Transit Company. The land on which the 1883 ball park and later Nicollet Park occupied remained in the Carpenter family until 1951, when it was sold to Northwestern National Bank of Minneapolis, which constructed a branch office on the site after Nicollet Park was torn down.

In 1884, Minneapolis joined the Northwestern League and played its games at a structure in the vicinity of 17th Street between Portland and Chicago avenues. The ballpark contained a grandstand that could seat 1,300 and two pavilions that accommodated another 1,000 each. The grandstand was fitted with “dressing and retiring rooms for both gentlemen and ladies and bathrooms for the players,” according to the St. Paul-Minneapolis Pioneer Press of Monday, May 19, 1884. The grounds were supplied with 100 posts for horses, and the facility was enclosed with 12-foot-high fences.

Within a couple of years, the team, which eventually became known as the Millers, was a couple of miles away, playing in a small ball field by the Milwaukee railroad lines just off Lake Street and Minnehaha Avenue. Just a few blocks south, where 36th Avenue and Minnehaha Avenue come together, was not a baseball complex but a horse track that was large enough–if need be–to fit a baseball game inside the track. And from 1895 through 1909 the Minnehaha Driving Park was needed for Sunday baseball games. During this time, the Millers’ regular home parks were in neighborhoods that frowned on such frivolity on the Sabbath.

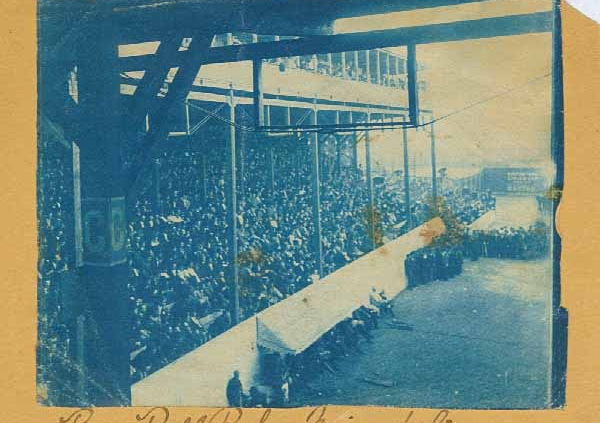

The first prominent base ball facility in Minneapolis was Athletic Park, a bandbox at the corner of Sixth Street and First Avenue North, behind the West Hotel in downtown Minneapolis. Estimates are that the distances down the foul lines were barely 250 feet, creating some high home run totals even in this era of the dead ball. So small was the park that players had to frequently “leg out” base hits to right field, and it wasn’t uncommon for a runner to be thrown out at first base on an apparent single to right.

The Millers began playing at Athletic Park in 1889. They produced a winning record that season, made a run at the pennant in 1890, and got off to another good start the following year. However, while they were in first place in August of 1891, the Miller’s pennant hopes crashed and their season came to a premature halt. The team was forced to disband because of financial problems, leaving Minneapolis without professional baseball.

To fill the void, the Milwaukee team of the American Association, a major league in its final year of operation, transferred its final series of the season, against Columbus, to Athletic Park in Minneapolis. The teams’ reasons for playing a neutral site game may have gone beyond the altruistic notion of providing entertainment to baseball-starved fans in a city that had lost its team. According to the St. Paul Pioneer Press, “Having lost all prestige in their own towns the two teams sought to run up to Minneapolis and replenish their exchequers.”

No one’s exchequer found much replenishment, though, as inclement weather prevented the playing of two of the games. But on October 2, 1891, despite heavy clouds that threatened rain or snow, Minnesota hosted its first–and until the Minnesota Twins arrived in 1961, its only–major-league game as Milwaukee beat Columbus, 5-0. The Brewers’ Frank (Red) Killen, who had started the season with Minneapolis and had hurled a no-hitter for the Millers the year before, held the visitors scoreless on six hits.

Columbus’ best scoring chance came in the third when Jack Crooks doubled and went to third on Tim O’Rourke’s sacrifice; however, Crooks was nailed at the plate trying to score on Charlie Duffee’s fly to Tom Letcher in right. The Brewers got on the board in the fourth when Eddie Burke was hit by a pitch, took third on Jack Easton’s wild pickoff attempt, and scored on a passed ball with two out. Milwaukee broke the game open in the fifth with four runs, getting four of their five hits that inning, including two doubles, a run-scoring single by Killen, and a two-run homer by Jack Carney. Burke scored the final run on another passed ball.

The teams then escaped the cold weather in Minneapolis, going back to complete their season with one last game in Milwaukee on October 4. This also proved to be the end of the American Association as a major league; it disbanded soon after with the National League absorbing four of its teams. But in its final days, the Association did provide Minnesota with its first major-league game.

The Minneapolis Millers continued to be the main attraction at Athletic Park, and, a few years later, produced a slugger able to take full advantage of the ballpark’s tiny dimensions. First baseman Perry Werden hit 42 home runs in 1894; 37 were at Athletic Park. The next year, Werden hit 45 homers, setting an organized-baseball record for home runs in a single season that lasted until Babe Ruth took up the business more than two decades later. Werden wasn’t the only heavy hitter on the team; the mighty Millers averaged over ten runs scored per game in 1894 and 1895. However, their pitchers were equally adept at giving up runs, and the Millers finished no higher than fourth either year.

The frequent parades across home plate might have continued indefinitely, but in May of 1896 the Millers were given their eviction notice from Athletic Park. The land on which their grounds stood, only one block from the main street of Minneapolis, had been sold and they were given thirty days to find a new home. On May 23rd, the Millers played their final game at Athletic Park. They left on a road trip and returned three weeks later to find a new home, Nicollet Park, in south Minneapolis.

The site of Athletic Park is now occupied by Butler Square, a retail and office complex, which is across 6th Street North from the Target Center, home of the National Basketball Association’s Minnesota Timberwolves.

Sources

“Base Ball,” Minneapolis Tribune, Tuesday, July 18, 1876, p. 4.

“Our National Game: The Blue Stockings Dedicate Their New Grounds,” Saint Paul and Minneapolis Pioneer Press, Wednesday, July 19, 1876, p. 6.

“Ball Dedication of Blue Stocking Grounds,” St. Paul Dispatch, Wednesday, July 19, 1876, p. 4.

“A Fitting Close: Minneapolis Wins the Last Game on the Old Grounds,” Minneapolis Tribune, Sunday, May 24, 1896, p. 3