Braves Field (Boston)

This article was written by Ray Miller

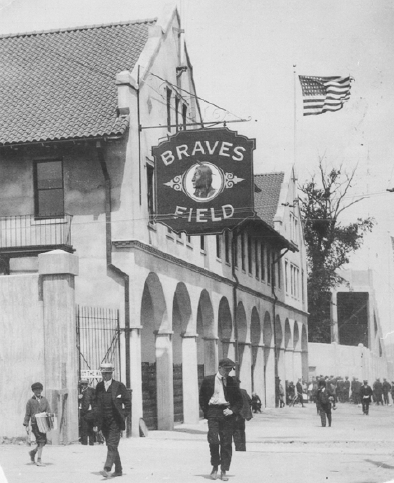

A crowd heads toward Braves Field. The ticket and administration building (shown at left) still stands and today serves as the headquarters for the Boston University police. Note the trolley tracks in the foreground, indicating the path of transit vehicles exiting from within the ballpark itself. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Introduction

Braves Field was a marvel when it opened in 1915: “the perfect ballpark” (Boston Globe1); “the world’s largest ballpark ever” (team owner James E. Gaffney); “baseball’s first superstadium” (historian Michael Gershman). It was where Babe Ruth made his first World Series start, and it was his final baseball home nearly 20 years later. It was the site of the first major-league game ever played on a Sunday in Boston, and Ted Williams made his Boston debut there, going hitless in a City Series game on April 15, 1939. It was the site of Boston’s first major-league night game, the 1936 All-Star Game, and three World Series. Although it was often derided as too big, too chilly, and too dirty, old Braves fans still declare that, in the early 1950s, at least, it “was the prettiest park in the majors.”2 Certainly, during the Braves’ last hurrah in Boston, Braves Field was a fine place to take in a baseball game, but ultimately it was doomed by a series of strategic miscalculations at its inception — coupled with the fact that in 23 of its 37 seasons, the team finished in sixth place or lower.

The team that was to become the Boston Braves had been the most successful National League club in the nineteenth century. No other NL team won as many championships during that era (eight), and only the Providence Grays had a better winning percentage. This powerhouse played at the South End Grounds, a tiny wooden facility in northern Roxbury that was wedged between Columbus Avenue to the south and the New York, New Haven, and Hartford railroad tracks to the north. In its final incarnation, between 1894 and 1914,3 it was a drab, poorly maintained facility that could not be enlarged because of its location. By the 1910s it was, in Harold Kaese’s memorable phrase, “an ugly little wart,”4 while the “few [fans who] wanted to watch the luckless Braves hated to make the trek to the field, which was badly located and had no modern conveniences.”5 When New York contractor and Tammany Hall insider James E. Gaffney bought the moribund team in December 1911,6 he immediately renamed it the Braves (after the Tammany syndicate’s symbol, Delaware Chief Tamanend), and started looking for a new ballpark site. In the meantime, he made some alterations to the South End Grounds for the 1912 season,7and brought his team to the Red Sox’ Fenway Park for their Memorial Day doubleheader in 1913.

And then came 1914. Everyone knows the saga of the Miracle Braves: In last place on the Fourth of July, they suddenly caught fire and were in first place to stay by September 5. They won the pennant by 10½ games and swept the defending champion Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series. The Red Sox let the Braves use their sparkling new stadium for their September run and for their two home Series games. (They never did return to the South End Grounds.)8 In the end, the club led all National League teams in attendance for 1914. If he hadn’t known already, James Gaffney now understood just how profitable a pennant-winning baseball team could be — and if they could outdraw their rivals while playing most of their home games in a dump like the South End Grounds, what could they do in a big, modern stadium that was easier to get to? The time to build was now.

As late as November 13, the New York Times could report a rumor that Gaffney had sold the South End Grounds and “would have to depend on the generosity of [the Red Sox] to use Fenway Park.” In actual fact, at this time he was negotiating the purchase of the western portion of the old Allston Golf Club on Commonwealth Avenue, about a mile west of Kenmore Square.9 The size of the lot was 13 acres, and it cost $100,000. Gaffney announced the purchase on December 4.10 Ruzzo writes that Gaffney “became immersed in the details” of his new sports palace: He wanted nothing less than “the world’s greatest ballpark” for his world-champion club, and he had some definite ideas about what that should look like.

Building Braves Field

To bring his visions to life, Gaffney turned to the Osborn Engineering Company of Cleveland, a firm that had recently made a name for itself in ballpark construction: No fewer than 11 teams had recently built modern concrete-and-steel parks, and Osborn had been involved with six of them.11 Although, according to Ruzzo, the Braves owner had pored over the plans of these “jewel boxes”12 in order to “incorporat[e] the best features of each into” Braves Field, it really did not look much like these other stadiums. First, it lacked the quirky features that urban topography foisted on many of these other parks (for example, the short right-field wall in Ebbets Field, and Fenway’s now-famous left-field wall); Gaffney felt that they just interfered with the way the game was “meant to be played.” He loved inside-the-park homers, and thus wanted “the playing field to be so large that it would be possible to hit [them] in any direction”13 He also demanded the largest seating capacity in the majors — in other words, a cash cow to exploit the team’s new success. The lot he purchased was certainly big enough, and Osborn was able to deliver on both counts. Gaffney first revealed how the Braves’ new home was going to look when he showed a nine-foot-square architects’ model to “members of the press and invited guests at team headquarters on March 8, 1915.”14 The public got its first glimpse of what was to come the following day, in a Boston Globe article, “Here’s How the Braves New Home in Allston Will Look” the architects’ model was subsequently displayed in a downtown department-store window.15

To bring his visions to life, Gaffney turned to the Osborn Engineering Company of Cleveland, a firm that had recently made a name for itself in ballpark construction: No fewer than 11 teams had recently built modern concrete-and-steel parks, and Osborn had been involved with six of them.11 Although, according to Ruzzo, the Braves owner had pored over the plans of these “jewel boxes”12 in order to “incorporat[e] the best features of each into” Braves Field, it really did not look much like these other stadiums. First, it lacked the quirky features that urban topography foisted on many of these other parks (for example, the short right-field wall in Ebbets Field, and Fenway’s now-famous left-field wall); Gaffney felt that they just interfered with the way the game was “meant to be played.” He loved inside-the-park homers, and thus wanted “the playing field to be so large that it would be possible to hit [them] in any direction”13 He also demanded the largest seating capacity in the majors — in other words, a cash cow to exploit the team’s new success. The lot he purchased was certainly big enough, and Osborn was able to deliver on both counts. Gaffney first revealed how the Braves’ new home was going to look when he showed a nine-foot-square architects’ model to “members of the press and invited guests at team headquarters on March 8, 1915.”14 The public got its first glimpse of what was to come the following day, in a Boston Globe article, “Here’s How the Braves New Home in Allston Will Look” the architects’ model was subsequently displayed in a downtown department-store window.15

Ground was broken on the old links on March 20, 1915; the grand opening was originally scheduled for September 1. The diamond was sunk 17 feet below street level, and “[p]ainful attention was paid to making sure that drainage was superb.”16 The infield sod came directly from the South End Grounds. According to oft-quoted statistics originally provided by Kaese, 750 tons of steel and 8.2 million pounds of cement went into the new park, and that it cost the team $600,000 to build.17 Work progressed rapidly and the grand opening was moved up to August 18. The club invited 10,000 schoolchildren and several thousand other guests, some of whom received a florid formal invitation with Chief Tamanend’s profile embossed in gold at the top.18 Fourteen Massachusetts mayors were among the dignitaries, as was Governor David I. Walsh. Paying customers numbered 32,000, with at least 6,000 people turned away at the gate. The grand total was estimated to be around 42,000, the largest crowd ever to attend a baseball game up to that point, although a far cry from the grandiose official proclamation of 56,000. The formal raising of the 1914 championship banner took place immediately before the game, which the Braves won, 3-1.19 Later that year, World Series attendance records were set in Games Three and Four, when the Red Sox defeated the Phillies. The American League team also took over the Braves’ home in 1916, in the first, second, and deciding fifth games of the World Series against Brooklyn. Babe Ruth made his first Series start there in Game Two, a 14-inning, six-hit masterpiece that is still considered one of the greatest pitching performances in postseason history.

The Structure of Braves Field

As it was originally conceived, Braves Field was to have a covered single-deck grandstand that extended around the playing field from foul pole to foul pole, with a sizable bleacher section in right field stretching from the end of the grandstand almost to straightaway center.20 In this configuration, it would have seated about 45,000 spectators. However, in the end Gaffney “trimmed his design” to save money.21 When the first “bugs” entered Braves Field on August 18, they beheld a covered single-tiered grandstand that curved from first base to third base; this was flanked on either side by enormous mirror-image pavilions, each with unroofed seating on benches for 10,000. Finally, the right-field bleacher section had shrunk: it was now a tiny stand in straightaway right that could hold up to 2,000 fans.22 This became Braves Field’s most famous section, known to one and all as the Jury Box, after a waggish sportswriter counted just 12 people in it one day. Simple arithmetic shows that the seating capacity was thus reduced to 40,000, which was still greater than any baseball stadium up to that time.

As it was originally conceived, Braves Field was to have a covered single-deck grandstand that extended around the playing field from foul pole to foul pole, with a sizable bleacher section in right field stretching from the end of the grandstand almost to straightaway center.20 In this configuration, it would have seated about 45,000 spectators. However, in the end Gaffney “trimmed his design” to save money.21 When the first “bugs” entered Braves Field on August 18, they beheld a covered single-tiered grandstand that curved from first base to third base; this was flanked on either side by enormous mirror-image pavilions, each with unroofed seating on benches for 10,000. Finally, the right-field bleacher section had shrunk: it was now a tiny stand in straightaway right that could hold up to 2,000 fans.22 This became Braves Field’s most famous section, known to one and all as the Jury Box, after a waggish sportswriter counted just 12 people in it one day. Simple arithmetic shows that the seating capacity was thus reduced to 40,000, which was still greater than any baseball stadium up to that time.

For players used to the tiny South End Grounds, writes Harold Kaese, coming to Braves Field “was like moving from a modern three-room apartment into a nineteenth century mansion.” The new field had gargantuan dimensions: According to Green Cathedrals, it was over 402 feet down the left-field line; 375 feet in right; 461 feet to straightaway center field; and a jaw-dropping 542 feet to the farthest point in right-center.23 The park was surrounded by a 10-foot concrete wall; a large scoreboard was built into this wall in left-center.24 Fans entered Braves Field through arches in the handsome stucco ticket office on Gaffney Street, just behind the right-field pavilion. The team offices were on the second floor; Ralph Evans says that:

“The ticket sellers never had to handle large sums of money: there were trap doors in the ceilings of each ticket booth, and they would put the money they took in into baskets, and these would be drawn into the offices above. That not only made things easier for the ticket sellers — it meant the treasurer would … have the proceeds for the day’s game counted by the fifth inning.”25

Cognizant of the problems fans had had getting to the South End Grounds, Gaffney added a special convenience for them in his new park, an “in-stadium transportation facility,” courtesy of the Boston Elevated Railway: trolleys came in off Commonwealth Avenue via Babcock Street and deposited fans onto the same courtyard pedestrians entered through the arches off Gaffney Street. This feature was greatly appreciated, as we see from reminiscences in the literature.26

Experiencing Braves Field

While the initial reaction to Braves Field was gushingly positive,27 at the core of Gaffney’s vision were several miscalculations (exacerbated by some of the cost-cutting measures that altered his original plan) that ultimately affected the fan experience adversely. Not all were his fault, certainly: As we shall see, the game simply changed not long after the stadium was built, and Braves Field was “relegated … to premature functional obsolescence.”28 In any event, the next two games in the new plant drew only 9,300 souls combined, and this was a sad harbinger of things to come.29

Ruzzo and others credit Gaffney for taking the economically canny step of funding construction in part by selling off the valuable Commonwealth Avenue frontage and setting Braves Field at the back of the lot, down by the Charles River and the Boston & Albany train yards. However, in the end this proved to be a penny-wise, pound-foolish move: Fans soon realized that a chilly east wind frequently blew in off the river over the outfield walls, and that it carried with it acrid, sooty smoke from the railroad tracks. Kaese quips that the team thus did local “cleaners and launderers a good turn,” and one old fan asserts that a dry cleaners was eventually located next door to the park for this very reason.30 It is true that the builders were able to take advantage of the steep ravine that cut across the lot (and had driven down the asking price): The slope created a good pitch for the right-field pavilion. And Ed Burns, in his 1937 profile of the park for the Chicago Tribune, asserted that “[e]very seat [in the covered grandstand] gives an excellent view of the entire playing field;”31 indeed, the expansive roof was supported by only 16 posts, fewer than in other new ballparks, so that there were fewer obstructed seats.32 However, some fans found the sightlines in the facility less than ideal: “The grandstand had a very gradual slope to it. So consequently people sitting in these seats had difficulty seeing the action.”33 Unlike in the original plan, half of the seats were on benches and exposed to the elements in those vast pavilions, and the seats toward the top were far from the action: Ruzzo estimates that there was a whopping quarter of a mile between the top rows of the left- and right-field stands. People seated in the pavilions close to the covered grandstand had to crane their necks. Finally, the angle formed by the curvature of the grandstand was more obtuse than in other parks, resulting in relatively more foul territory — and more seats farther away from the diamond.

James E. Gaffney sold the Braves in early 1916, making a handsome 267 percent profit on his original investment.34 (His estate continued to own Braves Field, however, until the 1940s, although the NL took over the lease in 1935.) In 1919 the local syndicate that bought the team from him sold it to a New York group, which five years later sold it to yet another New York-based outfit that included the colorful magistrate Emil Fuchs, who over the course of the next decade became a local sports legend for all the wrong reasons.35 None of these ownership groups was financially strong or willing to spend money to make the team a winner. (Fuchs himself was wealthy, but he did not know how to handle money and “owning the team [drove him] into bankruptcy.”)36 The National League finally forced Fuchs to sell his interest in the club in 1935; the group that took over from him was too large and unwieldy to work effectively.37 For the most part, throughout the 1920s and ’30s, “the Braves were broke,”38 and generally could not field a competitive team. Although Braves fans showed they would come to park when the team had promise — in 1933 and 1934, for example, the team finished fourth in both the National League standings and in league attendance — “Braves Field [in this period] became a deserted village.”39

If anything, the stadium only made the Braves’ situation worse. Compounding the discomforts discussed above was the fact that this parade of weak owners could not afford to maintain this “perfect ballpark” in good condition. Even more significantly, the style of baseball people wanted to see changed forever about five years after the cavernous park opened. Thanks to the exploits of Babe Ruth, people now wanted to watch baseballs soaring over the fences, not bounding toward them over a vast, green pasture. To put it mildly, Braves Field was not suited to the new power game. Kaese quotes Ty Cobb’s famous reaction after seeing the place for the first time: “One thing is sure: Nobody is ever going to hit a ball over those fences.”40 The first homer hit there (August 23, 1915) was a fluke: Pittsburgh’s Doc Johnston hit a ball that “got by the right fielder and rolled under a gate in front of the bleachers.”41 Other players bounced home runs through openings in the left-field scoreboard (e.g., “Bedford Bill” Rariden of the Reds on July 11, 1919). The first time a batted ball left the park was on May 26, 1917, when Walton Cruise of the Cardinals put one into the Jury Box. (It was Cruise who hit the second there, on August 16, 1921, this time for the Braves.) No one cleared the left-field wall on the fly until Frank Snyder of the Giants did it on May 28, 1925, almost 10 years after Braves Field opened. According to Kaese, this was a majestic 430-foot blast that “cleared the top of the fence by about 20 feet, some 15 feet from the foul pole.”42 Otherwise, the vast majority of home runs hit at Braves Field in the first 12 years of its existence were in fact of the inside-the-park variety: for example, according to Price, 34 of the 38 home runs hit at the park in 1921. The Giants once even hit four IPHR’s in one game there, on April 29, 1922.43

Starting in 1928, the Braves tried various stratagems to make their stadium feel cozier for hitters and fans: Inside fences were built, bleachers were added in left and center, home plate was moved around. The outfield dimensions changed — literally — on almost an annual basis into the 1940s, and Braves Field never looks the same in any two photographs from this period. Table 144 below gives you an idea of the extent of these constant renovations:

Table 1: Braves Field dimensions (in feet)

| Year | LF | CF | Deepest point | RF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1915 | 402.5 | 461 | 542 | 375 |

| 1928 | 320/353.5 | 387/417 | * | 310 |

| 1936 | 368 | 426 | * | 297 |

| 1946 | 337 | 370 | * | 340/320 |

Different figures are given for 1928 because Judge Fuchs had built “papier mache”45 stands in left and center to increase home-run production before the season opened, and then had them gradually disassembled after the opposition hit twice as many round-trippers as the home team. (“Anything hit into the skeleton of the great home run creation,” writes Burns, “was adjudged a two-base hit.”)46 Meanwhile, home plate was turned to the right in 1928, moved 15 feet closer to the backstop in 1936, then tilted right again in 1937 and 1946. When they moved the dish in 1937, they had to blast a notch out of the right-field pavilion in order to accommodate the shifted foul line. This notch is clearly visible in photographs of Braves Field, and helps to date them. After the addition of bleachers in front of the distant left-field wall, a new scoreboard was built over the Jury Box, where it remained till the team left town.47

Important events transpired in Braves Field in the 1920s and ’30s. This was where Joe Oeschger of the Braves dueled Leon Cadore of the Brooklyn Robins for 26 innings on May 1, 1920, the longest game by innings in major-league history. The first Sunday games ever played in Boston took place there early in 1929.48 Braves center fielder Earl Clark set a record with 12 putouts on May 10 of that same year. The NFL team now known as the Washington Redskins played their inaugural season in Braves Field in 1932, when they, too, were known as the Boston Braves. Babe Ruth made Braves Field his final major-league home in 1935, and homered and singled off Carl Hubbell there on Opening Day. There were the inevitable farcical moments, as well. For example, in 1926, “irregularities in the … turnstiles cost the club as much as $50,000.”49 Then, at the NL meetings in December 1934, Judge Fuchs floated the idea of having dog racing at Braves Field in 1935: The track would be built around the playing field, and the races would take place at night. Needless to say, Commissioner Landis did not approve.50 In 1936 the post-Fuchs regime tried to change the team’s fortunes by renaming them the Bees. Of course, that prompted the temporary rechristening of the ballpark, which received the resoundingly dull official new sobriquet National League Field, although the Beehive inevitably became its unofficial nickname.51 The newly christened Bees hosted the first All-Star Game in Boston that year on July 7. The National League won its first-ever All-Star Game, 4-3, defeating Lefty Grove. Cubs outfielder Augie Galan bounced a homer off the right-field foul pole for the decisive run. Alas, even here the team could not avoid tragicomedy: a newspaper mistakenly reported that the game was sold out, although there were plenty of pavilion seats available, and only 25,556 showed up — the smallest crowd in All-Star Game history. The Great Hurricane of 1938 hit Boston during the Bees-Cards game of September 21 — umpire Beans Reardon held off calling the game until “Tony Cuccinello yelled for a pop fly behind second base, only to have [catcher] Al Lopez wind up catching the wind-blown ball almost against the backstop.”52 Finally, Burns adds some interesting details about the Braves Field experience in the ’30s: the right-field pavilion was a haven for gamblers; the park featured “the only concession stand in the majors which carrie[d] a full line of chewing tobacco”; and the press box on the grandstand roof was “’Earache alley’ — the noisiest … in baseball.”53

The Three Little Steam Shovels and Braves Field’s Last Hurrah

The last decade of the team’s existence was arguably the happiest in its history. Three of the franchise’s small army of stockholders got “sick and tired of putting money into a constantly losing proposition”54 and staged a bloodless coup in early 1944, buying out the rest of the numerous syndicate. Lou Perini, Guido Rugo, and C.J. Maney were wealthy local contractors who soon became lovingly known as the Three Little Steam Shovels. They made every effort to make the club (by then once again called the Braves) a winning proposition, on the field and at the gate.55

The last decade of the team’s existence was arguably the happiest in its history. Three of the franchise’s small army of stockholders got “sick and tired of putting money into a constantly losing proposition”54 and staged a bloodless coup in early 1944, buying out the rest of the numerous syndicate. Lou Perini, Guido Rugo, and C.J. Maney were wealthy local contractors who soon became lovingly known as the Three Little Steam Shovels. They made every effort to make the club (by then once again called the Braves) a winning proposition, on the field and at the gate.55

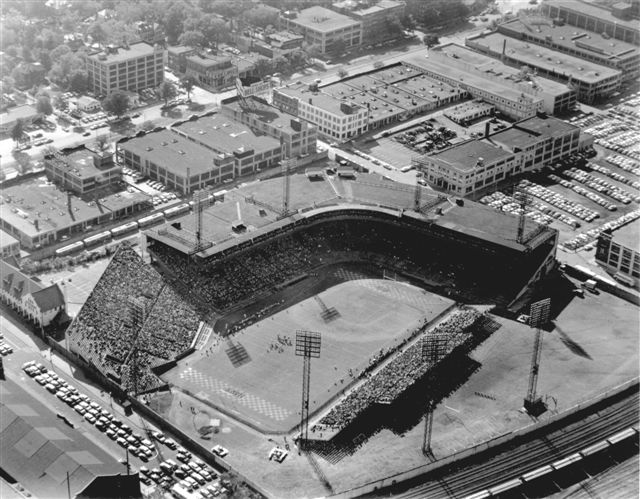

Starting in May 1944, when the team was on the road, the aggressive new owners made the physical renovations to Braves Field that gave it the appearance best remembered today. They shortened the distances in the outfield by installing a graceful two-level wooden inner wall from the corner of the left-field pavilion to right-center, with a low chain-link fence in front of the Jury Box to the big right-field stand.56 Light towers were installed for 1946, and the first night game in Boston was played on May 11, “with neon foul poles and shimmering sateen uniforms that made the players look like a men’s chorus.”57To improve the sightlines from the grandstand, the plate was once more turned to the right for 1946, and the infield was lowered 18 inches during a two-week road trip in June 1947.58A huge new scoreboard was installed in left field for the 1948 season; and “Sky View Boxes” on the grandstand roof were also added around this time.59 Finally, the upper half of the inner wall in center was removed in 1951, and fir trees planted behind the fence “to hide … the huge clouds of … locomotive smoke” from the railroad yards beyond.60

For all the renovations the team’s different owners made to Braves Field over the years, “they still [couldn’t] find a way to move 8.2 million pounds of concrete stands closer to the playing field,”61 but Perini et al. might have come the closest with the intangible changes they introduced that made the stadium the beloved “Wigwam” fondly remembered today. Braves fans realized that a new era had dawned after Opening Day 1946, when the team turned what could have been perceived as a “same-old-Braves” gaffe into a public-relations bonanza. Due to unfavorable weather conditions, the fresh paint on some of the grandstand seats had not dried by game time, and several thousand spectators left the park with green stains on their clothes. “An Apology to Braves Fans” immediately appeared in local papers in which the team offered to reimburse dry-cleaning expenses. Nearly 13,000 claims poured in from far and wide, and the club eventually paid off over 5,000 of them, at a cost of nearly $7,000.62

From that point forward, led by their new publicity director, Billy Sullivan, the Braves became “the team that called their fans ‘family.’”63 Fans had “a warm feeling” at Braves Field in the late ’40s, and “felt like [they were] at home” — “even the ushers were friendly!”64 Sullivan introduced Fan Appreciation Day, and the Braves Minstrels (a/k/a the Three Little Earaches), who serenaded fans throughout the park. The Braves gave away cars and teamed up with local hotels and restaurants on special promotions for night games.65 Concessions were upgraded, and came to include “the best fried clams … in all baseball.”66 The team in those days also fielded likable players who were happy to interact with the fans, especially Tommy Holmes who became the favorite of the vocal denizens of the Jury Box — to the point where they would harass any Braves player who took his place in right field!67

The most famous individual fan in these happy days was probably the redoubtable Lolly Hopkins, who shouted encouragement to the home side through a big megaphone, and brought Tootsie Rolls to every game for the players on both teams. It is emblematic of the relationship between the team and its fans that the Braves players presented Lolly with a bracelet before a 1947 game, as a token of their appreciation.68

The pinnacle was reached in 1948, when the Braves won their first pennant in 34 years and hosted the Cleveland Indians in the World Series. Three Series games were played at the Wigwam, the Braves taking Game One and dropping the other two, including the decisive Game Six. The team set a home attendance record by drawing over 1.45 million fans. Overall, 5,970,324 people visited Braves Field between 1946 and 1950, by far the only stretch in the park’s history that the team was able to exploit its large seating capacity so profitably.69The park itself, according to Ralph Evans, was, at the end, “the prettiest … in the majors — I defy anyone to say it wasn’t!”70 Ever progressive, the Steam Shovels integrated Boston baseball in 1950, when they brought outfielder Sam Jethroe to Braves Field.

Alas, this momentum simply could not be maintained. In 1951 the Braves finished fourth, as they had in the previous two seasons, but drew only 487,475 fans to their home games; that was fewer than any other NL team, almost only half as many as they had drawn in 1950. The 1952 figures were even worse: They finished seventh, and had a home attendance of 281,278; only 4,694 souls showed up for Opening Day. Mort Bloomberg remembers that “[c]rowds were so small that people’s voices would reverberate throughout the park. If you sat on the first base side, you could hear individual fans’ comments on the third base side.”71 He also felt that “[t]he park itself did not help draw fans”: For one thing, “[p]arking was non-existent.”

The sad fact was that the Braves had a slimmer margin of error than most other major-league teams: they had long been the “other team” in Boston, the Red Sox were now perennial contenders, and no one was willing to come to Braves Field to watch a mediocre team, no matter how friendly the ushers were. Perini finally threw in the towel and moved to Milwaukee immediately before the start of the 1953 season. (Only 420 season tickets had been sold.) Game tickets for 1953 were dumped onto the field, where they were burned.72 Some people certainly took the move hard, of course. A group of local teens who called themselves the Mountfort Street Gang broke into the deserted stadium one night, shortly after the move was announced and

“using nothing but their bare hands, they dug home plate out of the clay.Mind you, it was sunk 17” into the ground, and they had only their hands! … All these years, it was hidden in cellars, in attics, under beds, and then, all of a sudden, this guy brings it out and presents it to us [at the 40th reunion of the 1948 pennant winners in 1988]!”73

Many old Braves fans agree that if Perini et al. had been able to hang on for one more year, they just might have been able to hold on in Boston: The team had a strong nucleus of good ballplayers, and they wound up winning the NL pennant only six years after leaving New England. Ralph Evans claimed that there were plans to renovate Braves Field thoroughly in 1954-55, but Peter Gammons reported on ESPN in 1997 that Lou Perini had planned to abandon the park in the early 1950s for a new facility at Riverside in Newton; this plan fell through when Tom Yawkey refused to let the Braves use Fenway Park.74

After the Move

Boston University purchased Braves Field for the back taxes on July 29, 1953. It stood vacant for several months, though fans would occasionally come to the empty park to meditate. Once one of them took a home movie, which has been uploaded to YouTube. Eerily silent, it shows the outfield wall in its final incarnation, with the fir trees standing behind left-center, an overgrown infield, and high grass in the outfield. The BU Terriers football team played their home games in a virtually unaltered Braves Field until 1955, when over the course of several months the inside walls were removed, and the Jury Box and left-field pavilion were torn down. (The giant scoreboard was shipped to Kansas City for the use of the just-transplanted A’s.) Several curious overhead photographs exist showing a truncated Wigwam in this football configuration. A young Johnny Unitas made his first NFL start on this field during a Baltimore Colts-New York Giants exhibition game in 1956. The final baseball game was played there in the spring of 1959, between Boston University and Boston College.75

Boston University purchased Braves Field for the back taxes on July 29, 1953. It stood vacant for several months, though fans would occasionally come to the empty park to meditate. Once one of them took a home movie, which has been uploaded to YouTube. Eerily silent, it shows the outfield wall in its final incarnation, with the fir trees standing behind left-center, an overgrown infield, and high grass in the outfield. The BU Terriers football team played their home games in a virtually unaltered Braves Field until 1955, when over the course of several months the inside walls were removed, and the Jury Box and left-field pavilion were torn down. (The giant scoreboard was shipped to Kansas City for the use of the just-transplanted A’s.) Several curious overhead photographs exist showing a truncated Wigwam in this football configuration. A young Johnny Unitas made his first NFL start on this field during a Baltimore Colts-New York Giants exhibition game in 1956. The final baseball game was played there in the spring of 1959, between Boston University and Boston College.75

The old grandstand was finally razed in late November 1959. The football field was realigned to run parallel to the right-field pavilion, which now became the southern grandstand. The notch blown out of the pavilion in 1937 was filled in, and the opposite end was squared off to extend seating further toward the end zone. Eventually, dormitories and the Case Athletic Center were built where the grandstand and left-field pavilion had once stood, and the facility was renamed Nickerson Field. Meanwhile, the distinctive ticket office became the headquarters of the BU campus police department. In this configuration, James Gaffney’s sports emporium became the first home to the Boston (later, New England) Patriots, who played the first game in American Football League history there on September 9, 1960, as well as an assortment of other professional sports teams: the Boston Minutemen of the North American Soccer League (1975); the U.S, Football League Boston Breakers (1983); another Boston Breakers, of the Women’s United Soccer Association (2001-2003); and the Boston Cannons of Major League Lacrosse (2004-2006). It was last renovated in July 2009, when a four-lane track was put in around the playing field. Now, BU boasts that Nickerson Field is “a 10,412 seat, FIFA-approved Field Turf facility.”76

You can still take a tour of Braves Field: More of it was left standing than of any of the other classic steel-and-concrete ballparks built between 1909 and 1923 and subsequently abandoned. The old office building and right-field pavilion still stand; until the summer of 2010, you could see much of the original concrete wall in right, or at least what was left of it.77 Ralph Evans is able to indicate exactly what remains of the old plant and what was subsequently added by Boston University, and he can point out the approximate location of home plate, the third-base dugout, where the grandstand wall stood, and other important points of reference.78

This article originally appeared in “Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady. To read more articles from this book at the SABR Games Project, click here.

Sources

“Atlanta Braves Team History & Encyclopedia”. Baseball Reference.com

baseball-reference.com/teams/ATL/.

“Boston the Way It Was — Part 3: The Boston Braves.” Video, accessed at youtube.com/watch?v=JycSH_0uRfc.

Brady, Bob. “Model View,” Boston Braves Historical Association Newsletter, Spring 2010, 3-4.

—–. “A Streetcar Named Braves Field,” Boston Braves Historical Association Newsletter, Spring 2010, 4.

—–. “Going, Going …,” Boston Braves Historical Association Newsletter, Summer 2010, 4.

Burns, Ed. “Burns-Eye Views of Big Time Parks. Braves Field,” Chicago Tribune, 1937, accessed at Behindthebag.net behindthebag.net/category/burns-eye-views-of-big-time-parks/page/2/.

Gershman, Michael. Diamonds. The Evolution of the Ballpark (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1993).

Hirshberg, Al. The Braves: The Pick and the Shovel (Boston: Waverly House, 1948).

Johnson, Richard A. The Boston Braves (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2001).

Kaese, Harold. The Boston Braves (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948).

Lowry, Philip J. Green Cathedrals (New York: Walker & Company, 2006).

Mack, Gene. “Braves Field,” The Sporting News, January 15, 1947, 11.

—–. “Braves Field,” National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum Yearbook, Cooperstown, New York, 1984, 53.

Marazzi, Rich. “Four decades after their departure, the Braves (and their park) are fondly remembered by fans,” Sports Collectors Digest, September 29, 1995, 90-92.

Miller, Ray. A Tour of Braves Field (Boston: Boston Braves Historical Association, 2000).

—–. “South End Grounds,” The Northern Game — and Beyond. Baseball in New England and Eastern Canada, edited by Mark Kanter (Cleveland: SABR, 2002), 36-38.

“Nickerson Field.” Boston University Terriers Athletics Website, goterriers.com/facilities/nickerson.html.

Palacios, Oscar A., and Eric Robin, Grant Blair, Ethan Cooperson, Dan Ford, Tony Nistler and Mat Olkin. Ballpark Sourcebook (Skokie, Illinois: STATS Publishing, 1998).

Price, Bill. “Braves Field,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 7 (1978). research.sabr.org/journals/archives/online/40-brj-1978.

“Remembering the Wigwam: Braves Field & Nickerson Field.” Video: Boston University. Accessed at youtube.com/watch?v=r9q-MdefG-c.

“Remembering the Wigwam.” Boston University website, bu.edu/today/2012/braves-field-remembering-the-wigwam-2/.

Ritter, Lawrence J. Lost Ballparks (New York: Viking Penguin, 1992).

Ruzzo, Bob. “Braves Field: An Imperfect History of the Perfect Ballpark,” Baseball Research Journal Vol. 41, No. 2 (Fall 2012), 50-60.

Sullivan, George. “Memories of Braves Field,” Boston Globe, “Sports Plus,” September 30, 1977, 16-20.

Vincent, David W., ed. Home Runs in the Old Ballparks (Cleveland: SABR, 1995).

Notes

1 “Here’s How the Braves’ New Park in Allston Will Look,” Boston Globe, March 9, 1915; quoted in Bob Ruzzo, “Braves Field: An Imperfect History of the Perfect Ballpark,” originally published in Society for American Baseball Research, Baseball Research Journal (Fall 2012), 50-60.

2 Quote is from an interview with Ralph Evans of the Boston Braves Historical Association conducted on May 21, 1997, and used as the primary source of Ray Miller, A Tour of Braves Field (Boston: Boston Braves Historical Association, 2000), 11 (also see below); all subsequent quotes from Evans are from this interview. No one knows Braves Field better than Evans: he came from a family of dyed-in-the-wool Braves fans, and worked as a clubhouse boy at Boston University from 1955 to 1961, after the university had acquired the facility: “I would come to work early and just walk the park, up and down”; ibid., 1.

3 Whether you see the South End Grounds as one park extensively renovated two times, or as three different parks that bore the same name at the exact same location is probably a matter of personal preference. Ballpark historians now prefer the latter approach, and refer to the different plants as South End Grounds I (1871-1887), II (1888-1894), and III (1894-1914). For a brief history of the park, see Miller, “South End Grounds” in The Northern Game — and Beyond (SABR, 2002), 36-38.

4 Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948), 101.

5 Al Hirshberg, The Braves: The Pick and the Shovel (Boston: Waverly House, 1948), 15.

6 See Ruzzo, “Braves Field: An Imperfect History,” for more on Gaffney and the details of the purchase of the Boston NL franchise.

7 Kaese, 129.

8 There had been some disagreement about when the team left its old park in Roxbury. Kaese held that the Braves returned to the South End Grounds in 1915, playing there “until they began to move the infield sod over to their new park.” (Kaese, 173). However, all modern sources agree that they played in Fenway Park from mid-August 1914 until the grand opening of Braves Field.

9 See Ruzzo, “Braves Field: An Imperfect History.” The state eventually built the Commonwealth Armory on the eastern half of the golf course. A familiar landmark standing directly across from the right-field wall, the armory was demolished in 2002 to make way for Boston University’s Student Village.

10 See Ruzzo, who includes details of the purchase in footnote 21. Kaese states on page 173 that Gaffney’s big announcement came on December 1.

11 Namely, League Park in Cleveland and Comiskey Park in Chicago (1910); the Polo Grounds V in New York and Griffith Stadium in Washington (1911); Navin Field in Detroit; and Fenway Park (1912).

12 Ruzzo uses the term “jewel box ballpark” for all the classic concrete-and-steel stadia that were built between 1909 and 1915 (presumably counting Wrigley Field in Chicago, which was built in 1914 as Weeghman Park for the Federal League Whales). Gershman, on the other hand, reserves the term only for Fenway Park, Ebbets Field, and Wrigley Field (106), while classifying Braves Field, along with Yankee Stadium and a few other facilities, as a “superstadium.” See Michael Gershman, Diamonds. The Evolution of the Ballpark (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1993), 126 ff.

13 Kaese, 173.

14 See Bob Brady, “Model View,” in the Boston Braves Historical Association Newsletter, Spring 2010, 3.

15 Ruzzo, “Braves Field: An Imperfect History.” The fate of this model is heartbreaking: According to Brady, the model “gather[ed] dust in the attic of the former Braves administration building” (currently the Boston University police station) until 1992, when a university employee decided to smash it to pieces in an overzealous effort to clean up the area. A fragment of the model was saved in the nick of time by another employee who happened to be associated with the Boston Braves Historical Association and had planned to display it at the group’s first meeting on October 4 of that year. See Brady, “Model View,” 4.

16 See Ruzzo, “Braves Field: An Imperfect History.” Drainage could have potentially been an issue because there had been a large pond in this section of the old golf course; see Bill Brady, “An Engineer’s View of Braves Field in 1915,” Boston Braves Historical Association Newsletter, Summer 2014, 3-4.

17 Bill Price, in the article “Braves Field” (originally published in Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 7 [1978]), quotes a figure of “approximately $1,000,000.” He does not cite a source for it, or address the discrepancy with Kaese’s book, on which he otherwise relies for much of his information. Gershman (129) does call Braves Field the first “million-dollar ballpark,” but there is no indication that he intends this epithet to be taken literally. The Price article may be accessed online at research.sabr.org/journals/archives/online/40-brj-1978. Incidentally, Ballpark Sourcebook mentions the legend that draft animals were killed during the construction and remained buried under the area of third base (Oscar A. Palacios et al. Ballpark Sourcebook [Skokie, Illinois: STATS Publishing, 1998], 16). Ralph Evans also mentioned this story in the interview of May 21, 1997. A photograph of the ballpark under construction showing horses and mules at work hangs in the lobby of the Case Athletic Center at Boston University, in the general vicinity of where the left-field pavilion once stood.

18 The Braves’ invitation is reproduced in full in Richard A. Johnson, The Boston Braves (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia, 2001), 38.

19 Many sources include the details of the grand opening of Braves Field. See, inter alia, Kaese, 174.

20 See Miller, A Tour of Braves Field, 6b, for an image of Braves Field in this original configuration. This is a photograph of a model made according to the Osborn Engineering blueprints that has been displayed from time to time at meetings of the Boston Braves Historical Association. The model is identified in this earlier publication on 6 as representing renovations planned for 1954-55. It is possible, however, that any future expansion of Braves Field would, in fact, have reinstated the features dropped by Gaffney in 1915. See note 22 below.

21 Ruzzo, “Braves Field: An Imperfect History.” Brady, “Model View,” 4, suggests that another reason for cutting back was to “keep the project on its quick pace.”

22 This might have been a late modification. Ralph Evans points out that the right-field wall looks unfinished to the left of where the Jury Box once stood, as if the builders intended to extend the stands to that area. See photo #13 on page 4 of the “Photo Tour Gallery” toward the back of Miller, A Tour of Braves Field. Brady reports that the club had merely “set aside for later” extending the bleachers and grandstand roof, and that “such enhancements were under consideration during the Perini regime.” (Brady, “Model View,” 4). All this explains Ralph Evans’s contention that the model mentioned in note 20 was of what the park would look like after renovations in the mid-’50s.

23 Ballpark Sourcebook (17) generally agrees: it has 402 feet, 375 feet, 440 feet, and 550 feet respectively. Gershman, 130, displays a photograph taken during the 1916 World Series. It clearly shows a low fence extending from the Jury Box to the center-field wall and cutting off the deepest corner from the rest of the field. Whether this was a permanent arrangement or set up for the standing-room Series crowd is unclear.

24 See photo in Lawrence S. Ritter, Lost Ballparks (New York: Viking Penguin, 1992), 20.

25 See Miller, A Tour of Braves Field, 8.

26 See, for instance, the interview with Boston Braves fan Mort Bloomberg in Rich Marazzi, “Four decades after their departure, the Braves (and their park) are fondly remembered by fans,” Sports Collectors Digest, September 29, 1995, 91. Consult Ruzzo, “Imperfect History,” and Bob Brady, “A Streetcar Named Braves Field” (Boston Braves Historical Association Newsletter, Spring 2010, 4-5), for specific details of the Braves Field trolley service.

27 Ruzzo quotes an article in Baseball Magazine that calls it “the world’s greatest ballpark,” as well as NL President John K. Tener calling it “the last word in ballparks.” See Ruzzo, “Braves Field: An Imperfect History.” Both quotes are referenced in note 33.

28 Ruzzo, “Braves Field: An Imperfect History.”

29 See Baseball Reference.com: baseball-reference.com/teams/BSN/1915-schedule-scores.shtml; scroll down to the games of August 19 and 20.

30 Kaese, 173; Marazzi, 91.

31 From the series, “Burns-Eye Views of Big Time Parks,” by Ed Burns of the Chicago Tribune. There were 15 one-page articles in all, one for each park. (Sportsman’s Park served both St. Louis teams; incidentally, League Park and Cleveland Municipal Stadium are covered together in article No. 11.) They contain Burns’s own rather whimsical drawings of each park’s layout (with several captions), plus two columns of text that combine factual data with the author’s editorial comments. The website Behind the Bag has digitalized versions of Nos. 1-11 in the “Burns-Eye-View” series at behindthebag.net/category/burns-eye-views-of-big-time-parks/; they are given in descending order, which means you need to scroll all the way down for the Braves stadium (referred to by Burns as “National League Park”), which was first in the series. (For fans of the Red Sox, Fenway Park is covered in No. 8.) The article was originally published in the Chicago Tribune on June 6, 1937, on page B4.

32 See Lowry, Green Cathedrals (first edition, Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., 1992), 113.

33 Marazzi, 91. Ralph Evans vehemently disagrees with the allegation of faulty sightlines, but he remembers the more “fan-friendly” Braves Field of the last years.

34 See Ruzzo, “Braves Field: An Imperfect History.” Also Kaese, 174 ff. Gaffney accepted an offer of $500,000 for the team after paying a mere $187,000.

35 See Kaese (190-233) and Hirshberg (25-66) for entertaining accounts of the judge’s many misadventures. Kaese (193) emphasizes, however, that Fuchs also introduced a lot of fan-friendly features to the Braves experience, such as the first “broadcasting contracts for the Boston clubs” and a Knot Hole Gang for kids. The late George Altison, who served for many years as the president of the Boston Braves Historical Association, can be seen reminiscing fondly of his time in the Knot Hole Gang in “Boston the Way It Was — Part 3: The Boston Braves,” part of a television series about Boston in the 1930s and ’40s that first aired in 1995. It can be accessed on YouTube at youtube.com/watch?v=JycSH_0uRfc.

36 Ruzzo, “Braves Field: An Imperfect History.” Also see Kaese, 192.

37 This group originally included Charles F. Adams, founder of the Boston Bruins hockey team; however, as he owned the Suffolk Downs race track, Commissioner Landis eventually forced him to sell his stock (1941); and then, “[s]o many stockholders took over the team that it became a standard gag around the press room that owners out-numbered newspapermen at the bar after every ball-game” (Hirshberg, 75); on the convolutions of the Braves ownership situation between 1935 and 1944, see Hirshberg, 63-77.

38 Hirshberg, 31.

39 Hirshberg, 38.

40 Kaese, 173, 174. Ruzzo, “Braves Field: An Imperfect History,” includes another quote from the same interview that is telling: The Georgia Peach declared that the Braves’ new home was “the only field in the country on which you can play an absolutely fair game of ball without the interference of fences.” James Gaffney was not the only person in America who preferred “inside baseball” and thrilling extra-base hits in the 1910s.

41 See Price, “Braves Field.”

42 Kaese, 197. Two months after Snyder’s historical clout, Bernie Neis of the Braves outdid him by launching a drive in a game against St. Louis all the way onto the railroad tracks. Kaese writes that no one had hit a ball over the left-field wall even in batting practice until Neis did so on April 10 of that same year, four days before the 1925 season started.

43 Ritter, Lost Ballparks, 22. In all, there were 1,925 home runs of all types hit at Braves Field; see David W. Vincent, ed. Home Runs in the Old Ballparks (Cleveland: SABR, 1995), 12. For the record, the last homer at Braves Field was hit by Roy Campanella on September 21, 1952.

44 Figures are from Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals (New York: Walker & Co., 2006), 32, which graphically proves that the dimensions by no means remained constant in the periods between the years chosen for reference! Some comments: after the renovations of 1937, the right-field foul pole stood 376 feet from home plate; left-field figure for 1946 is technically from 1944, but Ritter claims that it remained constant into the 1950s (Lost Ballparks, 24). He also writes that the deepest point after the last major renovations in the mid-’40s was 390 feet to “deepest center.” By the way, there is no explanation given for the two different distances listed for right field in 1946.

45 The epithet is Ed Burns’s, from “Burns-Eye-Views of Big Time Parks,” Chicago Tribune, 1937.

46 “Burns-Eye-Views of Big Time Parks,” Chicago Tribune, 1937.

47 On the shifting of home plate and the concomitant alterations, see Ritter, Lost Ballparks, 24; the 1992 edition of Green Cathedrals (112), and Kaese, 235. On the right-field scoreboard (and the low esteem it was held in by Braves fans), see Hirshberg, 180-81; it is clearly visible above the Jury Box in photos and film footage from the final years.

48 Judge Fuchs passionately supported the referendum that passed in November 1928 to allow baseball on Sundays (Kaese, 207). The Braves were supposed to play the first Sunday game ever in Boston on April 21, 1929, but the game was rained out. It was the Red Sox, in the end, who had the privilege, losing to the A’s in Braves Field on April 28. (Due to a provision of the new law that still forbade Sunday ball in fields close to churches, the Red Sox had to play their Sunday home games at Braves Field until May 1932. See Kaese, 221.) The Braves finally played their first Sunday home game on May 5, 1929. Incidentally, Ruzzo, in “Braves Field: An Imperfect History,” contends that in 1918, “Gaffney and Red Sox owner Harry Frazee discussed the possibility of sharing Braves Field,” so that the latter could make a killing on the real estate market by selling Fenway Park.

49 Kaese, 200.

50 Hirshberg, 50-51. Also see Kaese, 227-28. Kaese suggests that the plan was to use the park exclusively for racing, with the Braves moving their home games to Fenway Park (“'[o]ver my dead body’ was the equivalent of Tom Yawkey’s quick reply,” Kaese, 227).

51 Bob Brady points out (email of December 5, 2014) that the full official name emblazoned on the ticket office/administration building during the “Bees” era was “National League Baseball Field,” but Burns uses the shorter name in his 1937 ballpark profile, and this is also what is listed as an alternate name of the facility in Green Cathedrals, 31. To further muddy the waters here, both Hirshberg (71) and Kaese (236) write that Braves Field was called “National League Park” at this time.

52 Kaese, 244.

53 “Burns-Eye-Views of Big Time Parks,” ChicagoTribune, 1937.

54 Hirshberg, 117.

55 On Perini, Rugo, and Maney, see Hirshberg, 116-25, and Kaese, 254-69.

56 See Kaese, 257, and consult the outfield dimensions given in Green Cathedrals, 32.

57 Kaese, 261, 263; aerial views of “The Wigwam” at night can be seen in old newsreel footage included in the short Boston University video “Remembering the Wigwam: Braves Field and Nickerson Field,” which can be accessed on YouTube at youtube.com/watch?v=r9q-MdefG-c.

58 Kaese, 263. Also Hirshberg, 180, who adds that this “job … was done while a rodeo was performed at Braves Field”!

59 On the new scoreboard, see Hirshberg, 180-81. None of the sources consulted state when exactly the boxes were installed on the grandstand roof, but Brady, in his November 15, 2014, email, informed us that the building of the “Skyview Boxes” was announced in a late 1947 issue of the team’s publication, the Braves Bulletin. Originally, they were only on the first-base side of the roof; a late 1948 issue of the Bulletin declared that Sky Views were being added to the third-base side for 1949. Also compare the two versions of the drawing of Braves Field by Gene Mack. The first was published in The Sporting News on January 15, 1947, 11, and shows no left-field scoreboard or seats on the grandstand roof; the second was a later revision, and is reproduced in National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum Yearbook for 1984, 53; it shows what is labeled the “new scoreboard” and the Sky View box seats on the first-base side of the roof, and mentions the Braves pennant of 1948. We have not yet found publishing information for this later drawing; the 1984 Hall of Fame yearbook states only, on 53, that this and the other ballpark cartoons it is reproducing are “courtesy of Mrs. Ruth (Mack) O’Toole.” The original drawings of 1946-47 can be viewed at baseball-fever.com/showthread.php?84778-1946-47-Sporting-News-Sketches-of-Major-League-Parks-by-Gene-Mack-Full-Set-of-14.

60 Marazzi, 91. The date is from Ralph Evans.

61 Kaese, 174.

62 See Kaese, 263-64; Hirshberg, 182; Marazzi, 91; also George Sullivan, “Memories of Braves Field” (Boston Globe, “Sports Plus,” September 30, 1977), 20. Kaese quotes a final outlay of “nearly $6,000,” while Hirshberg claims “the whole business cost the Braves over $7,000.” Green Cathedrals, 33, erroneously reports that the Braves had to play their remaining April home games at Fenway Park because of this incident; in fact, the team played the Dodgers at Braves Field on the following day, and held only their April 28 doubleheader vs. the Phillies at the Red Sox’ home park.

63 Quote from “Boston the Way It Was.” The Braves Family is also the name of the team film that Sullivan produced after 1947: the first-ever color film made by a baseball team. (Extensive footage from this film can be seen in “Boston the Way It Was.”) The black-and-white Take Me Out to the Wigwam, the first postseason film ever made in major-league baseball, appeared the previous year. Both films are available digitally through Rare Sports Films and contain priceless footage of Braves Field. Sullivan later became famous as owner of the New England Patriots NFL team.

64 From reminiscences in “Boston the Way It Was.”

65 For more on Sullivan’s many promotions, see Kaese, 262-64, 268 (“Three Little Earaches” on 263); Hirshberg, 178-85; Sullivan, 18; Marazzi, 91.

66 See the first edition of Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., 1992), 112.

67 See Hirshberg, 104-113.

68 On Lolly Hopkins, see “Boston the Way It Was,” which includes film footage of her receiving her bracelet (in turn, this presumably comes from The Braves Family).

69 Total home attendance for this five-year period was 5,728,659; we have subtracted the home attendance for the games of April 28, 1946, when the Braves used Fenway Park after the “Wet Paint Incident” of Opening Day. The only years they drew over 1 million in Boston were 1947-1949.

70 Interview of May 21, 1997; see Miller, 10.

71 Marazzi, 92.

72 See photograph in “Remembering the Wigwam: Braves Field and Nickerson Field.”

73 Miller, A Tour of Braves Field, 10-11. The Braves Field plate is now in the Sports Museum of New England.

74 As reported on August 31, 1997; the same story appeared in the Boston Globe. Of course, if this were true, why wouldn’t the Braves just use Braves Field while their new park was being built?

75 Ralph Evans interview. According to Sullivan, “(C)ollege baseball attracted big crowds there in the ’20s.” Sullivan, “Memories of Braves Field,” 16.

76 See the page on the Boston University Athletics website: goterriers.com/facilities/nickerson.html. For more of the history of Nickerson Field from a BU perspective, see the article “Remembering the Wigwam” on the university website, at bu.edu/today/2012/braves-field-remembering-the-wigwam-2/. During the late 1990s, when Evans and this author collaborated on the print edition of his annual Braves Field tour, there was concern that BU was going to tear down all of what was left of the old ballpark. See Miller, A Tour of Braves Field, 11.

77 See Bob Brady, “Going, Going …” in Boston Braves Historical Association Newsletter, Summer 2010, 4.

78 Evans says “he paced every square foot” of the park after starting to work as the BU clubhouse boy in 1955: “I would come to work early and just walk the park up and down.” He also was able to study the original blueprints.