Hinchliffe Stadium (Paterson, NJ)

This article was written by David Krell

Once a gem, its luster long since faded along with its utility, Hinchliffe Stadium stands as a relic of a working-class city proud of its baseball heritage and teeters on the precipice of revival. Paterson, New Jersey, lays claim to this storied facility, once the renowned site of Negro League games, but it is hardly the only visual hallmark for the metropolis known as “Silk City” because of its bygone silk industry. Great Falls is a jewel among many in the Garden State’s crown of scenic beauty, ranking with Cape May’s Victorian-style buildings, Jersey City’s Liberty State Park, Hoboken’s train station, Princeton’s Battlefield State Park; Long Beach Island’s shore line, and Atlantic City’s boardwalk.

Paterson became a household word when comedian Lou Costello, whose statue stands at the entrance of the memorial park bearing his name, regularly mentioned his hometown in dialogue for The Abbott & Costello Show, a 1950s syndicated television program that added to the duo’s impressive roster of credits in burlesque, radio, and films — 36 between 1940 and 1956. Costello also did one solo film, The Thirty Foot Bride of Candy Rock in 1959. He passed away that year at the age of 53.

Named for William Paterson, the second New Jersey governor, Paterson emerged from a vision by Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. Treasury Secretary. The Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration summarized Hamilton’s attraction to the area: “Even during the Revolution, Alexander Hamilton had been impressed with the site of the Great Falls of the Passaic. His fertile imagination envisioned a great manufacturing center to supply the needs of the country. Here was the water power to turn the mill wheel and a navigable river to carry the manufactured goods to the market centers.”1 And so, the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures was born — S.U.M.

Paterson became a manufacturing force growing in population, political importance, and stature for sportsmen. Baseball historian John G. Zinn notes that “baseball clubs” in Paterson’s chronicles dates back to “as early as 1855” with the “premier” team in those formative years débuting in 1864 — the Olympic Base Ball Club.2 The Silk Sox, an aptly named squad following the template of sports teams paying homage to local color, had semipro credentials. Though it honored the city’s famed silk output, the team played on a Clifton ball field.3

It was against this backdrop that a city the size and stature of Paterson demanded a stadium for its citizens. Mayor John Hinchliffe heralded the new facility in his Annual Message for the 1931 Fiscal Year: “The city stadium will fill a need that has long been recognized. It will be self supporting and in time the City will be compensated for all that has been spent.”4 Hinchliffe also noted that the idea for a stadium had been floated in the early 1920s.5

The long wait ended on July 8, 1932, with a début celebrating Independence Day, albeit a few days late.

Fittingly, Paterson was a Revolutionary War site, a fact not lost on the unnamed reporter for the Paterson Morning Call recounting the day’s events, which included actors depicting George Washington’s biography with scenes about his childhood, military training, ascent to general, and presidential inauguration: “On the very ground made sacred by Washington and his immortal heroes of the revolution, Paterson last night, through a pageant of 1,500 persons and an audience numbering fully 7,000 have memorable expression of its patriotism and its reverence for the ‘Father of His Country,’ whose 200th birth anniversary the nation and the world honors this year.”6

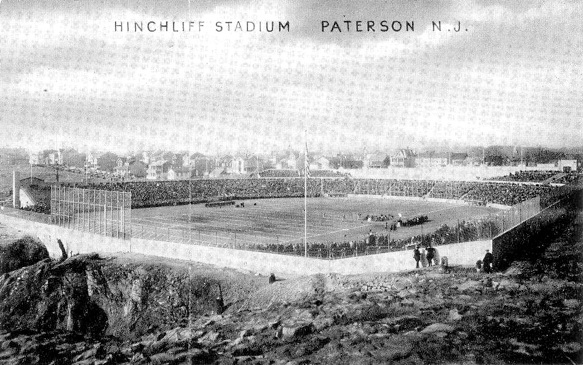

Designed in the Art Deco style, an architectural form embracing sleekness with little ornamentation — the Empire State Building and Los Angeles City Hall are two prominent examples — Hinchliffe Stadium had a foothold in New Jersey sports. It became a political site in 1933, when silk industry workers held a meeting that attracted 15,000 in a protest.7 The structure is described as “originally very near square” by the National Park Service; the dimensions were 440 feet by 417 feet. Presently, it’s 590 feet by 417 feet. It held about 10,000 people. Like other ballparks, Hinchliffe served additional sports, including soccer, football, and boxing. In the early 1980s, Astroturf replaced natural grass. Local architect John Shaw designed Hinchliffe Stadium; he was a partner in the Fanning & Shaw firm. But the famed Olmsted Brothers should be credited as well because they saw the possibility of a ballpark when they created a plan to develop the property for the Passaic County Parks Commission.8

Built in the Depression, Hinchliffe stands on a “commanding bluff above the Passaic River.”9 With the city’s downtown area and Great Falls in sight, Hinchliffe is a Paterson landmark abundant in baseball history. Though the structure had a square-like shape, the seating formed an oval around the grounds, which made them suitable for racing in addition to baseball.

Baseball fans could soon claim the stadium as a Negro Leagues attraction, hosting the likes of Larry Doby and Buck Leonard before baseball’s integration took hold after Jackie Robinson broke the racial barrier in 1947.

It was the site of a game marketed as “the Colored Championship of the Nation” in 1933; the Philadelphia Stars defeated the New York Black Yankees.10 Hinchliffe then became a site for the Black Yankees. It was a turning point for the team. “For the first time in their history the New York Black Yankees have a home ground,” reported W. Rollo Wilson in the June 30, 1934, edition of the Pittsburgh Courier. “For the past five weeks they have been using Hinchliffe Stadium, Patterson [sic], New Jersey, on Sundays and have played to crowds of 2,000 and more.”11

The New York Cubans also occasionally played at the Paterson ballpark in 1935 and 1936.12 They lost the 1936 season opener to the Negro League champion Pittsburgh Crawfords 19-6 at Hinchliffe.13

When Hinchliffe received the status of a national historic landmark in 2014 from the National Park Service — the first for a baseball-only structure — Larry Doby Jr. said of his father, “He just would have been extremely proud that they are restoring it, because it had so many great memories for him. And the first memories of him here are playing football for Eastside High School against Central on Thanksgiving. That was his favorite sport in high school. They used to have overflow crowds here, it was a big deal. And then, obviously, later, trying out for the Newark Eagles, which is the beginning of everything here. It’s a big day for this town, and it would be a very proud day for him.”14

Doby became the first black player in the American League, beginning his Major League Baseball career in July 1947, just three months after Robinson’s début with the Brooklyn Dodgers. He played with the Cleveland Indians from 1947-1955, then played a couple of years with the Chicago White Sox, returned to Cleveland for one season, and ended his career in 1959 with stints in Detroit and, again, the White Sox. The Baseball Hall of Fame inducted Doby in 1998.

Hinchliffe Stadium has earned a place in the annals of other sports. Midget-car races drew audiences after World War II. Former champs Jack Dempsey and Joe Louis were referees of fights in the 1940s, adding stature to Hinchliffe’s boxing matches. Abbott & Costello performed there; it had special meaning to Costello because he grew up in Paterson. Hinchliffe also ranks high in the development of television. Dumont, the original fourth television network, telecast fights in 1946; a Hinchliffe boxing card was the first telecast of a New Jersey sports event.15

As of the writing of this article (2018), Hinchliffe Stadium is in the process of renovation after two decades of neglect. It began in 2009, when President Obama signed the Omnibus Public Lands Management Act, which included a mandate to investigate and assess the “potential for designation as a National Historic Landmark (NHL), as well as options for the preservation of Hinchliffe Stadium.”16

In turn, the National Trust for Historic Preservation classified the stadium as one of the “ten most endangered sites in the United States.”17 In 2013, the stadium that once hosted Josh Gibson, Monte Irvin, and Satchel Paige became a National Historic Landmark. It was an important step towards renovating and reviving Paterson’s once-gloried site. There was hope for Patersonians that saw other sites destroyed from abandonment; Jersey City’s Roosevelt Stadium, where Jackie Robinson played his first game in Organized Baseball on April 18, 1946, for the Montreal Royals, the Dodgers’ AAA farm team, was destroyed in 1985. “The DEP will continue to work with local officials, the Friends of Hinchliffe Stadium, and all of the stadium’s supporters to develop plans that will ensure the long-term preservation of this facility that means so much to the history of our nation,” emphasized Richard Boornazian, New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection Assistant Commissioner for Natural and Historic Resources.18

The preservation effort not only maintains the physical structure of the stadium but also honors its societal impact. “It’s of great interest because it represents important chapters in the national narratives about baseball history, segregation, and civil rights,” explains Gianfranco Archimede, Paterson’s Director of Historic Preservation. “Hinchliffe hosted Negro League baseball for 10 consecutive seasons. It’s one of three surviving stadiums to host Negro League games. When Jackie Robinson broke the color line, the stadium’s use lessened.”

“Hinchliffe’s restoration and preservation have many stories. It’s a geography story, an archaeological story, a sports story, a civil rights story, an architecture story, a politics story, and a Paterson story. We’ve done an incredible amount of due diligence in the investigation regarding below-ground testing, contamination, and the physical structure.”19

The stadium’s legacy has inspired Patersonians and other patrons to advocate for restoring this wonderful gathering place for future generations. Consequently, numerous grants have been received and the city has floated bonds to provide additional financing.

Neglect, nonuse, and obsolescence have descended Hinchliffe Stadium from a facility representing a blue-collar citizenry to a void that has historic value but an uncertain future. The journey towards restoration began with an investigation into Hinchliffe’s architectural, historic, and legacy value. It’s a byzantine process that must not only reveal a highly significant rationale for investment of time, money, and materials to revive a long-dormant site, but also overcome any prejudice dismissing sports as a societal cornerstone. While schoolchildren learn the civil rights contributions of Rosa Parks, Medgar Evers, and Martin Luther King Jr., their knowledge about Josh Gibson, Jackie Robinson, and Satchel Paige is likely scant, if it even exists. Hinchliffe Stadium’s place in that chronicle is a basis for the revival effort.

The National Historic Landmark Nomination describes, “The Stadium’s design, materials and workmanship survive intact and clearly impart the original and historic appearance and construction of the building. Although years of vacancy and vandalism have damaged the building, it remains as one of the most intact, if not the most intact of the few remaining stadiums that retain important historical integrity, associated with Negro baseball. Hinchliffe is distinctive, not only because of its unique design, but because it retains its entire physical plant, rather than just a field or lot where games were played. The ultimate test for integrity for Hinchliffe Stadium is whether members of the New York Black Yankees, or Newark Eagles, or Cuban Stars, Bacharach Giants, Pittsburgh Crawfords, or any of the other teams that played there, or the spectators, or participants in the other sporting events of the 1930s would recognize the place if they were able to return. Undoubtedly they would.”20

Last revised: October 30, 2018

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Phil Williams and verified for accuracy by the BioProject fact-checking team.

Photo credit: Friends of Hinchliffe Stadium

Notes

1 “Paterson, the ‘Federal City,’ Stories of New Jersey, School Bulletin, Prepared For Use In Public Schools By The Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration, December 1936.

2 Peter Morris, William J. Ryczek, Jan Finkel, Leonard Levin, Richard Malatzky, eds., Base Ball Founders: The Clubs, Players and Cities of the Northeast That Established the Game, McFarland & Company, Inc., 218.

3 Ibid.

4 John V. Hinchliffe, Mayor of Paterson, New Jersey, “Annual Message of the Mayor,” Paterson, New Jersey, Fiscal Year, 1931.

5 Ibid.

6 “Bicentennial Pageant at Stadium Thrills Thousands with Spectacular Display,” Paterson Morning Call, July 9, 1932: 1.

7 “15,000 Silk Strikers Hold Demonstration,” New York Times, October 3, 1933: 4.

8 Continuation Sheet, National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service.

9 “Preservation Snapshot: Hinchliffe Stadium in the Silk City,” https://www.state.nj.us/dep/hpo/1identify/nrsr_15_Nov_Hinchliffe.pdf

10 “Hinchliffe Stadium,” National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service.

11 W. Rollo Wilson, “Off To Fine Start, The Yanks See Big Season,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 30, 1934: 14.

12 Mark Newman, “NJ Negro Leagues park gets landmark status,” MLB.com, April 16, 2014, Last accessed July 25, 2018.

13 William E. Clark, “Pittsburgh Crawfords Win 3-Game Series From Cubans Before Large Crowds At Negro League Opening,” New York Age, May 16, 1936: 9.

14 Newman, “NJ Negro Leagues park gets landmark status.”

15 Continuation Sheet, National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service.

16 National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/NHL/news/LC/fall2012/HinchliffeES.pdf, Last accessed July 26, 2018.

17 Ibid.

18 State of New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, “Christie Administration Announces National Historic Landmark Designation For Paterson’s Hinchliffe Stadium,” news release, March 11, 2013, https://www.nj.gov/dep/newsrel/2013/13_0020.htm, Last accessed August 18, 2018.

19 Telephone interview with Gianfranco Archimede, Director of Historic Preservation, Paterson, New Jersey, July 26, 2018.

20 Hinchliffe Stadium, National Historic Landmark Nomination, Prepared by Paula S. Reed, Ph.D., Architectural Historian and Edith Wallace, MA, Historian; Edited by Robie Lange, Historian, National Park Service, National Historic Landmarks Program, September 4, 2012, https://www.nps.gov/history/nhl/news/LC/fall2012/Hinchliffe.pdf, Last accessed July 27, 2018.