Metropolitan Park (New York)

This article was written by Bill Lamb

At the close of the 1883 season, the Metropolitan Exhibition Company confronted a logistics problem: the operation of its two major league baseball clubs — the New York Gothams (later Giants) of the National League and the New York Metropolitans of the American Association — from a single, overtaxed north Manhattan ballpark: the original Polo Grounds. The solution subsequently devised by the company brain trust required relocation of the Mets, the company’s less-favored team, to a new home field situated about ten city blocks to the east.

The results of the move were mixed. At quickly constructed Metropolitan Park, the Mets were near-invincible on the diamond, winning better than 80% of the games played there. But players, fans, and segments of the sports press hated the place. Before the season was out, Metropolitan Park was abandoned. Several years later, it was dismantled. And today, this unloved and short-lived ballpark is long forgotten.

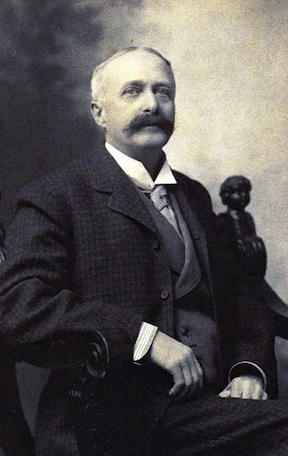

The life and death story of Metropolitan Park is enmeshed in the history of professional baseball in New York during the 1880s. The National League had expelled the Brooklyn-based New York Mutuals at the close of the 1876 season.1 Since then, greater Gotham had been without a major league baseball club. Revivification began in 1880 with the formation of the Metropolitan of New York club, an independent professional nine financed by well-heeled cigar manufacturer and baseball enthusiast John B. Day. Like other New York clubs, the Mets began their playing existence in Brooklyn, then a municipality separate and distinct from New York and the nation’s third largest city.2 But Day, a recently-arrived Manhattan resident and Tammany Hall member, wanted his ballclub to play in New York City proper. By then, the real property needed for placement of a ballpark was no longer available in densely-populated and industrialized lower and midtown Manhattan. So Day looked northward, eventually setting his eyes upon vacant meadowland located just north of Central Park at Fifth Avenue and 110th Street. Happily for Day, the property, owned by socialite-sportsman James Gordon Bennett, Jr., the publisher of the New York Herald, was available for rent. And it offered another plus: a portion of the grounds was already enclosed, a legacy of the polo club that had formerly used but since departed the premises.

The life and death story of Metropolitan Park is enmeshed in the history of professional baseball in New York during the 1880s. The National League had expelled the Brooklyn-based New York Mutuals at the close of the 1876 season.1 Since then, greater Gotham had been without a major league baseball club. Revivification began in 1880 with the formation of the Metropolitan of New York club, an independent professional nine financed by well-heeled cigar manufacturer and baseball enthusiast John B. Day. Like other New York clubs, the Mets began their playing existence in Brooklyn, then a municipality separate and distinct from New York and the nation’s third largest city.2 But Day, a recently-arrived Manhattan resident and Tammany Hall member, wanted his ballclub to play in New York City proper. By then, the real property needed for placement of a ballpark was no longer available in densely-populated and industrialized lower and midtown Manhattan. So Day looked northward, eventually setting his eyes upon vacant meadowland located just north of Central Park at Fifth Avenue and 110th Street. Happily for Day, the property, owned by socialite-sportsman James Gordon Bennett, Jr., the publisher of the New York Herald, was available for rent. And it offered another plus: a portion of the grounds was already enclosed, a legacy of the polo club that had formerly used but since departed the premises.

Once a lease was secured, the Mets were installed at the “Polo Grounds,” beginning play at their new home field with a September 29, 1880 victory over the Nationals of Washington, before some 1,000 paying spectators.3 Playing an assortment of local semipro, college, and amateur teams thereafter, the Mets completed an abbreviated first campaign with an encouraging 16-7-1 log (which included a 15-6 victory over Manhattan College hurled by 33-year-old club owner Day himself). Smitten with this taste of success, Day was eager to move his ball club on to bigger things. To underwrite his ambitions for the team, Day formed the Metropolitan Exhibition Company (MEC), with himself as president and dominant shareholder. The other members of the closely held, four-member enterprise were Tammany Hall cohorts Joseph Gordon, Charles T. Dillingham, and Walter S. Appleton. In reality, however, the MEC was a one-man operation, with Day in complete and unilateral control of the New York Mets.

Prior to the 1881 season, Day funded the construction of a spacious grandstand and other seating accommodations at the Polo Grounds. That season, the Mets played a mixed Eastern Championship League/freelance schedule that included 60 games against National League competition. The Mets’ decent 18-42 record against the big leaguers thereafter prompted organizers of the American Association, a newly formed rival of the NL, to offer Day a place for his club in their fledgling circuit. But for the time being, Day declined. The 1882 Mets schedule again combined a mix of games against major league opposition and local squads. And once again, the Mets played the big leaguers tough, winning 29 of 74 contests against NL foes, while taking all but one game against AA opposition. In the process, the Mets generated a handsome after-expenses profit for the MEC — and this despite a modest 25 cents general admission price to the ballpark.

In 1883, John B. Day took the plunge, entering the ranks of big league owners — with two different clubs. The Mets, with MEC minority shareholder Gordon acting as club president, became a member of the American Association. Shortly thereafter, Day announced that an entirely new ballclub, formed around players from the just-disbanded Troy Trojans, would enter the National League. This NL club, called the New York Gothams, or simply the New-Yorks, was headed by Day himself. The home field of both MEC clubs would be the Polo Grounds. To accommodate the Mets, a new landfill-based diamond with its own admission gate and grandstand was placed in the southwest quadrant of the Polo Grounds. As befitted their preferred status as Day’s club, the Gothams were assigned the established diamond with grandstand on the southeast portion of the property.

During the season, the Gothams and Mets largely avoided simultaneous home games. But on 12 occasions the two clubs were in dual action at the Polo Grounds.4 Their respective outfields were separated only by a temporarily erected canvas fence. This arrangement was aesthetically unsatisfactory — ballplayers from one league occasionally hopped the fence and ran onto the outfield of another league in pursuit of long-hit balls.It was also financially unsound — the MEC’s two clubs were, in essence, competing with each other for the date’s New York baseball fans. Clubs visiting the Polo Grounds to play either the Gothams or the Mets also were also disenchanted with ongoing simultaneous games, while league officials, particularly American Association higher-ups, wanted Mets games decoupled from those of the National League Gothams.5 Perhaps more important to the MEC, the Mets were no longer profitable,6 attracting only 50,000 fans to 46 home dates. Only the Gothams, with 75,000 fans paying the 50 cents general admission charge at a minimum, kept company books in the black for the 1883 season.

To remedy the problem, the MEC decided to move the Mets. Although ballpark-sized real estate was available in north Manhattan, suitable locations in the Polo Grounds’ Central Park North neighborhood were not.7 Rather, the Mets’ new field, unoriginally named Metropolitan Park, would be built on waterfront property in East Harlem, about a mile-plus distant from the club’s former home. At the time, East Harlem was hardscrabble territory, consisting of ethnic Irish, German, Italian, and Jewish enclaves interlaced by gas works, factories, tar pits, stockyards, and garbage dumps, and bordered on the east by the Harlem River. Still, expectations for the ballpark were high, with the New York Clipper reporting that “it is expected that the new grounds of the Mets will be the handsomest in the country.”8

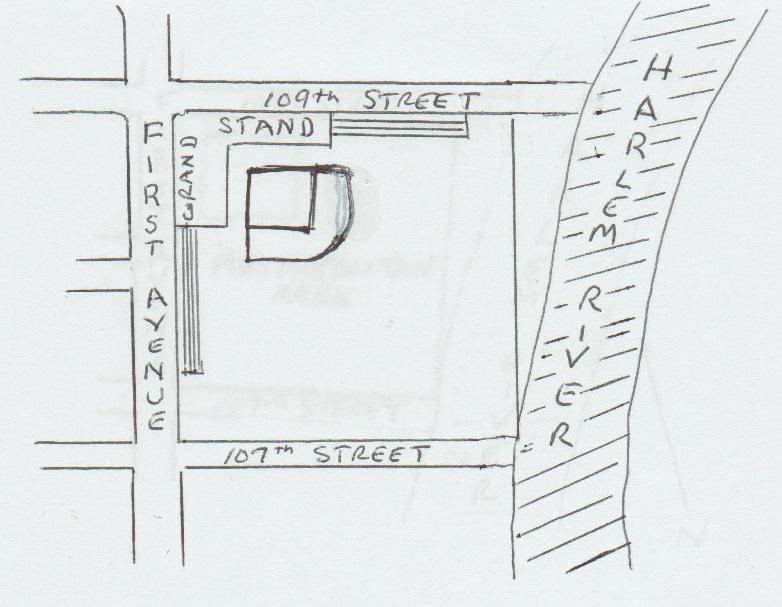

On February 13, 1884, construction of Metropolitan Park began, with completion optimistically projected for April 1.9 The site ultimately chosen was a former city dump10 situated on two city blocks fronted by First Avenue, and bounded by 109th Street to the north and 107th Street to the south.11 To the east, the distance to the left field fence was dictated by the adjacent Harlem River.12 The precise contours of completed Metropolitan Park, including its foul line distances, have been lost to time. But the ballpark does not seem to have been particularly small or oddly-shaped.13 No photograph or other contemporaneous image of Metropolitan Park survives, but the ballpark’s geographic location and general layout are reflected in the crudely drawn diagram embedded herein.

Building plans called for a 5,000 seat, single-tier wooden grandstand to be constructed behind home plate. Unreserved seating for 5,000 more spectators was slated for the third base (109th Street) and first base (First Avenue) sidelines.14 When completed, the grounds, including left field by the river, would be enclosed by 14-foot-high walls.15 For transportation, fans heading to Metropolitan Park would be serviced by elevated trains running along Second and Third Avenues, and by waterfront stops made on game days by the ferries of the Harlem Steamboat Company.16

Inconveniently, Metropolitan Park construction was “retarded by the weather.” Nevertheless, club management still hoped that the grounds would be ready for baseball by mid-April.17 Those hopes, however, were dashed by a violent wind storm in early April that destroyed much of the ballpark’s bracing and carried away nearly 300 feet of fencing.18 While carpenters and other workmen repaired the damage, the Mets preseason exhibition game schedule was transferred to the Polo Grounds. Metropolitan Park still was not ready when the 1884 regular season opened, but the Mets, whether by fortuitous circumstance or prescient design, opened the campaign with a nine-game road trip. The team had finished in the middle of the pack in 1883, and little was expected from them, but the Mets broke from the gate smartly, winning six of their season-opening away games.

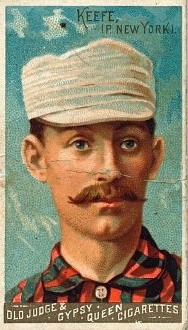

When completed, the seating capacity of Metropolitan Park, at approximately 5,000, was only about half that projected in earlier press reports. And the field itself was not quite ready for play when Opening Day finally arrived. Nevertheless, the Mets’ new ballpark was unveiled as scheduled on May 13, 1884, with Pittsburgh Alleghenies as opponent. According to a New York Herald report, “the ground was crowded with spectators, and before the hour for the game to begin there was not a vacant seat in the grandstand.”19 Prior to the first pitch, the Seventh Regiment band entertained the crowd, variously estimated in the 4,000 to 4,500 range (which included the city Board of Aldermen and about 1,000 other freeloaders).20 Once the action began, the Mets quickly gave right-hander Tim Keefe a 4-0 lead. From there, the future Hall of Famer breezed home, pitching the Mets to a comfortable 13-4 victory.

Although praise for the Mets’ performance was uniform, reviews for Metropolitan Park were decidedly uneven. Most observers found the grounds pleasing to the eye. The New York Herald described the ballpark as “presenting a beautiful appearance,”21 while the New York Times lauded Metropolitan Park for “a neat appearance …beautifully laid out, afford[ing] spectators a good view of the game.”22 Yet teviewers with a sensitive nose were less impressed. The New York Evening World commented that the neighborhood surrounding Metropolitan Park was “by no means a choice one,” before adding that the playing field was composed from landfill refuse and was “of such a nature as to be decidedly unpleasant to the olfactory organs.”23 An out-of-town report was even less charitable, remarking snidely that the new ballpark was “surrounded by the Italian colony, and the air from the gas-houses and flats is not very salubrious.”24 To add further to fan discomfort, Metropolitan Park’s placement amidst neighborhood factories meant that foul, sometimes dangerous, smoke often wafted over the grounds.25

Worse yet for club management, Mets players hated the ballpark. Pitcher Jack Lynch, the team’s resident wit, reportedly observed that infielders at Metropolitan Park “could go down for a grounder and come up with malaria.”26

Notwithstanding their disdain of Metropolitan Park, the Mets played outstanding ball there, winning 15 of their first 20 home games. But after the encouraging attendance of Opening Day, fans stayed away. Barely 500 were in attendance for the second game played at Metropolitan Field, a 4-2 victory over the Alleghenies. Only about 1,000 fans witnessed burly Mets first baseman Dave Orr launch the first shot over the left field wall in a 6-3 win over Washington some ten days later. The first game of a holiday split-doubleheader on Decoration Day drew “the largest number of spectators that have ever attended a morning game in this city.”27 Otherwise, contests at Metropolitan Park rarely drew over 1,500 fans,28 the rough break-even point to cover the club’s daily expenses — even though the Mets were playing winning baseball and in the thick of the American Association pennant chase. Ten blocks west, meanwhile, the lackluster Gothams (headed for a tie for fourth place in the NL) were drawing markedly larger crowds to the Polo Grounds — at twice the general admission price.

On June 19 and with their record standing at a sterling 26-9, the Mets departed for a month-long road trip. While the club was away, the MEC decided to pull the plug on Metropolitan Park. When the Mets returned, their home games would be played at the Polo Grounds. Metropolitan Park was used only on seven July-August dates when the Gothams had a home game scheduled.29 Apart from the odd boxing exhibition and clay pigeon shooting tournament, Metropolitan Park otherwise lay dormant for the remainder of the 1884 season.

The Mets featured the yeoman hurling of Tim Keefe (37-17 in 483 innings pitched) and Jack Lynch (37-15 in 496 innings pitched),30 the batting of first baseman Dave Orr (.354 BA with 112 RBIs, both AA highs) and third baseman Dude Esterbrook (.314). They also had an astute steward in non-playing manager Jim Mutrie. Thus, they cruised to the American Association title, finishing at 75-32 (.701), a comfortable 6 1/2 games ahead of the Columbus Senators. Notwithstanding their dissatisfaction with the grounds, the Mets had been even better playing at Metropolitan Park, going 26-6-1 (.813) at their forsaken home field.

The Mets featured the yeoman hurling of Tim Keefe (37-17 in 483 innings pitched) and Jack Lynch (37-15 in 496 innings pitched),30 the batting of first baseman Dave Orr (.354 BA with 112 RBIs, both AA highs) and third baseman Dude Esterbrook (.314). They also had an astute steward in non-playing manager Jim Mutrie. Thus, they cruised to the American Association title, finishing at 75-32 (.701), a comfortable 6 1/2 games ahead of the Columbus Senators. Notwithstanding their dissatisfaction with the grounds, the Mets had been even better playing at Metropolitan Park, going 26-6-1 (.813) at their forsaken home field.

From there, things quickly spiraled downhill for the Mets. In the forerunner to the modern World Series, the club was swept by the National League champion Providence Grays in three sparsely attended postseason games played at the Polo Grounds. Even counting the Providence match, Mets attendance had been a disappointment, barely cracking the 50,000 mark despite winning the AA championship.

During the offseason, the MEC determined that the Mets would be sacrificed to bolster the fortunes of the profitable Gothams, the pet of company boss Day. To that end, Mets manager Mutrie was transferred to the Gothams, and later, via some rule-bending chicanery, the Day club acquired the services of Mets stars Keefe and Esterbrook. As the Gothams improved, the Mets went into rapid decline, finishing the 1885 season as a seventh-place non-contender (44-64, .407). That winter, the MEC sold the Mets to railroader-entrepreneur Erastus Wiman, who promptly relocated the club to amusement grounds on Staten Island. Two dreary seasons later, the New York Metropolitans were defunct, their player assets sold to the Brooklyn Grays and the franchise hulk assigned to Kansas City.

The fate of Metropolitan Park was no happier. To the extent that the grounds were used at all, the ballpark served as home field for the crack amateur team of the NYC Fire Department during the summers of 1885-1886.31 Thereafter, the record goes silent. But in all probability, Metropolitan Park was dismantled sometime shortly after the 1886 baseball season ended, the grounds being of no use to the MEC as a ballpark, but having value as marketable real estate. More than a century later, the site of long-gone Metropolitan Park is occupied by a high-rise apartment building. Its elevation affords residents a scenic panorama of the neighborhood where a championship baseball club had played generations earlier.

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Rory Costello and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

The principal sources of the narrative above are Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Walker & Company, 2006); David Nemec, The Beer and Whisky League: The Illustrated History of the American Association — Baseball’s Renegade Major League (New York: Lyons & Burford, 1994); Stew Thornley, Land of the Giants: New York’s Polo Grounds (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000), and contemporaneous reportage by New York City daily newspapers and Sporting Life. Unless otherwise noted, statistical data have been taken from Retrosheet.

Notes

1 The Mutuals and the Philadelphia Athletics were permanently banished from the National League for failure to complete the road-game portion of their 1876 playing schedules.

2 At the time, New York City consisted of Manhattan and the western portion of the Bronx. Brooklyn, Queens, East Bronx, and Staten Island would not be incorporated into the city until 1898.

3 As recalled years later in “John B. Day Tells of Bitter Hour,” New York Times, February 6, 1916.

4 As calculated from ballpark statistics published by Retrosheet. Including a May 30 doubleheader, the Mets posted a 4-8-1 record playing on the Southwest diamond on dates when the Gothams were in action on the adjacent Polo Grounds field.

5 As per Stew Thornley, Land of the Giants: New York’s Polo Grounds (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000), 19.

6 Per Sporting Life, April 9, 1884. Although the Mets were now considered “sort of a white elephant,” the club could still be operated by means of the “healthy reserve from profits made from 1882.”

7 The switch from weekend polo matches to daily baseball games did not sit well with the residents of tony Central Park North. In time, neighborhood allies on the city council successfully promoted the traffic grid plan that led to the razing of Polo Grounds I after the 1888 season.

8 New York Clipper, February 2, 1884.

9 See “Baseball,” New York Herald, February 13, 1884.

10 Per David Nemec, The Beer and Whisky League: The Illustrated History of the American Association — Baseball’s Renegade Major League (New York: Lyons & Burford, 1994), 62.

11 As announced in the New York Herald, February 16, 1884, and elsewhere.

12 Both the above New York Herald article and present-day commentary on Metropolitan Park have the grounds bounded by the East River. But that is a geographic impossibility. The East River did not run pat Metropolitan Park, as it turns away from Manhattan at East 96th Street and then meanders northeast toward Long Island Sound. The waterway that ran past the left field of Metropolitan Park above 107th Street was the Harlem River, the eight-mile Hudson River tributary that defines the northern end of Manhattan Island.

13 When Metropolitan Park was completed, the major complaint about the playing dimensions was the placement of home plate. It was so close to the grandstand that foul balls routinely soared out of grounds, necessitating game delays while ballpark stewards tried to retrieve the balls from lurking “Street Arabs.” Elsewise, a new ball had to be put into play. The Mets home opener required the use of a then-excessive half-dozen baseballs to complete the game, as reported in “Three Championship Games,” New York Herald, May 14, 1884, and “Metropolitan Park: Opening of the New Ground,” Sporting Life, May 21, 1884.

14 According to construction plans reported in Sporting Life, February 6, 1884.

15 Ibid.

16 Thornley, 19.

17 See “The Eve of the Baseball Season,” New York Tribune, March 24, 1884.

18 As reported in Sporting Life, April 9, 1884.

19 Per “Baseball Games,” New York Times, May 14, 1884.

20 See e.g., “Metropolitan Park: Opening of the New Ground,” Sporting Life, May 21, 1884: “Over 4,000 attended the first game at Metropolitan Park,” and “Three Championship Games,” New York Herald, May 14, 1884: Some “4.500 spectators taxed seating capacity to the utmost limit.” Other news accounts were less numerically specific, the New York Sun, May 14, 1884, observing that the crowd “almost filled up all the space outside the field proper,” while the New York Tribune, May 14, 1884, merely noted the “large crowd present” for the game.

21 “Three Championship Games,” New York Herald, May 14, 1884.

22 “Base Ball Games,” New York Times, May 14, 1884.

23 New York Evening World, May 14, 1884.

24 Cleveland Leader, May 14, 1884.

25 Thornley, 20.

26 Per Nemec, 62.

27 New York Herald, May 31, 1884.

28 As per attendance estimates contained in Mets game reportage published in the New York Times.

29 As reflected in ballpark stats published by Retrosheet. Unlike the previous season, the alternate Southwest diamond at the Polo Grounds was never used for simultaneous Gothams-Mets games in 1884.

30 Apart from a six-inning complete-game victory posted by Buck Becannon on the season’s final day, the Keefe-Lynch tandem pitched every inning of the New York Mets 1884 season.

31 As reflected by passing mention in “Notes of the Game” columns published in the New York Times.