Sprague Field (Bloomfield, NJ)

This article was written by Bill Lamb

Located about 15 miles west across the Hudson River from midtown Manhattan, Bloomfield is an older, mostly blue-collar New Jersey town with a rich athletic tradition. To continue this heritage, the municipality maintains more than a dozen greenswards suitable for the play of outdoor sports. One of these is Felton Field, a small, tidy playground wedged into a densely populated neighborhood not far from the town borders with Newark and East Orange. Few, if any, present-day Bloomfield residents likely appreciate that the playground’s undersized diamonds (used only for Little League and softball games) sit on the site of a vanished ballpark that once hosted amateur, semipro, minor league, and Negro Leagues baseball. This now-forgotten venue — constructed in April 1919 and demolished around 1940 — was called Sprague Field.1

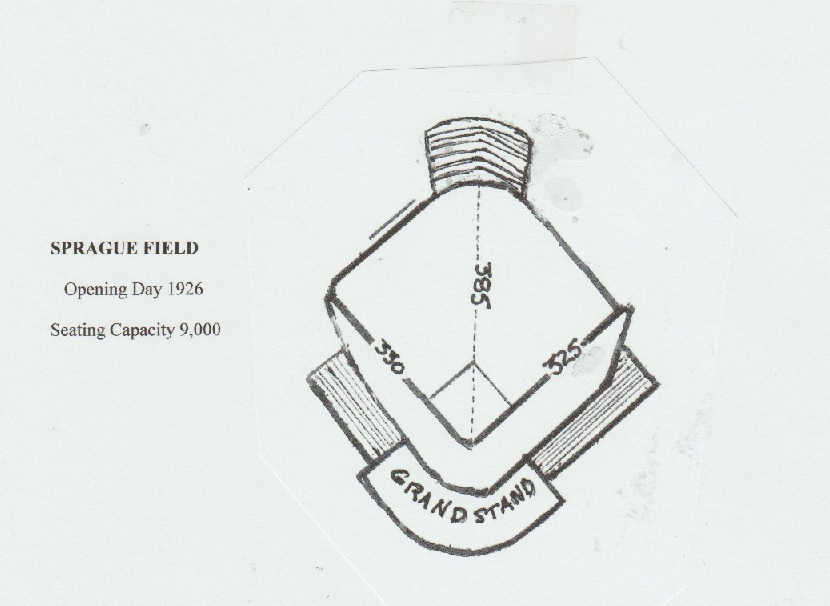

A century ago, Bloomfield was home to several large industrial plants, including the works of the Sprague Electric Company, a subsidiary of General Electric.2 In early 1919, the company purchased open space near its plant and began the construction of an athletic field for the off-hours recreation of its 2,000 employees. A feature of the grounds was a baseball diamond intended for use by the Sprague Electric company team.3 Ready for game action by mid-spring, the playing field dimensions were constrained by surrounding residences and commercial buildings but were adequate, if somewhat on the small side — LF: 330; CF: 385; RF: 325. Those dimensions were later defined by fencing that ranged from five feet high in left field, to a 35-foot scoreboard in left center, to ten feet in center and right field. Outside the fences, the ballpark was bounded by Bloomfield (first base line), LaFrance (third base line), Floyd (left field), and Arlington (center and right field) Avenues.4 Initially, the seating capacity of Sprague Field was limited. But by September 1920, up to 3,000 spectators could be accommodated following the addition of a wooden grandstand and bleacher sections.5

On May 3, 1919, the Sprague Electric nine inaugurated the new ballpark with a game against the Orange (NJ) Athletic Association.6 The company team then went on to capture the 1919 championship of the amateur North Jersey Industrial League, and repeated as league champs in 1920.7 Meanwhile, the grounds also served as home field for the top-notch Sprague Electric soccer team. In 1922, the competitive level of Sprague Field baseball was upgraded when the Bloomfield Elks secured a lease for Sunday games. Composed almost entirely of local talent, the team sponsored by the Elks was one of the best semipro clubs on the East Coast and played all comers, including elite black professional teams like the Bacharach Giants, Homestead Grays, and New York Cuban Stars.

In anticipation of the throngs expected to attend their games, the Elks embarked upon a ballpark enlargement program, funding improvements via off-season dinner dances, raffles, and other events that ultimately raised $7,000. By the time that the season commenced, permanent fencing had been erected and the seating capacity of Sprague Field doubled to approximately 6,000.8 Facing top-flight opposition, the Elks, with future Philadelphia A’s standout Mule Haas in center field, held their own, posting a 15-14 log for the 1922 season. Thereafter and with his sights set on bolstering the club’s roster, Elks field boss Jim Finnerty undertook a pre-1923 season recruiting tour. Among the newcomers signed to play for the Elks (at $3 a game) was a strapping Columbia University first baseman who played under the alias Babe Long. But after several games at Sprague Field, Long was deemed a bust — “He couldn’t hit,” lamented Finnerty — and dropped from the club.9 Later, the ex-Elk had Cooperstown-level success under his birth name: Lou Gehrig. The disappointing performance of recruit Long notwithstanding, the Elks turned in an outstanding 26-10-1 record that season. It concluded with a shutout victory pitched by Bloomfield resident Alex Ferguson, just home after completing a 9-13 campaign with the Boston Red Sox.10

The ensuing seasons saw the Bloomfield Elks at their zenith, drawing large crowds for Sunday and holiday doubleheaders against the likes of the Heinie Zimmerman Bronx All-Stars and the cream of black pro squads. Capacity crowds of 6,000 were the norm, but a reported 8,500 spectators swamped Sprague Field (with another 500 watching the action perched atop railroad cars parked nearby) for an Elks contest against a postseason barnstorming team of Detroit Tigers led by future Hall of Famer Heinie Manush.11 By the end of the 1924 season, the four-year cumulative record of the Elks stood at an excellent 95-52-3 (.647).12 Even brighter days seemingly lay ahead. Turmoil to the town’s immediate south, however, soon brought an end to the Bloomfield Elks as an elite semipro baseball club. Events also propelled Sprague Field — albeit only very briefly — into the ranks of minor-league ballparks.

For decades, the City of Newark had been the scene of top-notch minor-league baseball, most recently provided by the Newark Bears of the Class AA International League. But the Newark club had recently been plagued by financial instability and ballpark problems. Two playing sites — Wiedenmayer’s Park in the Newark Ironbound district and Harrison Field in nearby Harrison, NJ — had recently been destroyed by fire. That left the Bears to play in Meadowbrook Oval, a bandbox unsuitable for high-level baseball. In June 1924, the Bears had been dispossessed there as well, evicted on short notice by the Newark Board of Education, titleholder of the premises.13 The Bears had an option to use of Sprague Field in nearby Bloomfield, but chose instead to move into Newark Schools Stadium, an oval-shaped facility designed for football, not baseball. By May 1925, however, the ballpark situation had become untenable, forcing relocation of the franchise to Providence, where the club finished the season and then disbanded.

During the off-season, Long Island entrepreneur Charles Davids acquired International League rights to the Newark territory, and began preparations for investing an entirely new Newark Bears franchise in the city. To remedy the playing field problem, Davids purchased the site of burned-down Wiedenmayer’s Park and commenced construction of Davids (later Ruppert) Stadium. But as the 1926 season approached, it became obvious that the Bears’ new ballpark would not be ready for Opening Day. In near desperation, Davids approached Elks manager Finnerty and Bloomfield lodge directors about gaining temporary access to Sprague Field. Notwithstanding the imposition on their own schedule, the Elks agreed, a magnanimous gesture that earned the organization “the wholehearted thanks of Newark fandom.”14 A grateful Davids then quickly set about enlarging the seating capacity of Sprague Field by expanding the grandstand and erecting a new center-field bleachers section. Within weeks, the ballpark could accommodate 9,000 fans.15

On April 4, 1926, Sprague Field hosted its first contest between two clubs in Organized Baseball, a Newark Bears preseason exhibition game against the American League’s Philadelphia A’s. The Bears lost, 8-4. A week later, the newly enlarged grounds filled to capacity as the Bears topped the Philadelphia Phillies, 9-7.16 On April 14, the Bears initiated the International League season with a home victory against the Buffalo Bisons.

Before the day was out, however, calamity struck. A carelessly discarded cigarette started a fire that caused extensive damage to Sprague Field, with large portions of the wooden grandstand and bleacher sections destroyed. With the grounds at least temporarily unusable, club boss Davids secured permission from the Newark Board of Education to return the Bears to Newark Schools Stadium for a few games.17 And by mid-May, the club was able to move into a still-uncompleted but usable Davids Stadium. Meanwhile, the Bloomfield Elks were left with a wrecked ballpark. Reconstruction of the burned grandstand and bleacher sections would take at least a month, and was prohibitively expensive for a fraternal organization like the Elks to undertake in any event. For the remainder of the 1926 season, an unrepaired Sprague Field was usually dormant, as the Elks took to playing largely a road schedule.18 At year’s end, the lodge disbanded its baseball team, bringing the Bloomfield Elks’ brief run as a top-flight semipro outfit to a close.19

Although the Elks were leaving the competitive baseball scene, Sprague Field was not. Despite the fire damage, the ballpark still had usable seating for about 2,500 spectators, more than sufficient to meet the needs of a fledgling independent black pro team. The Newark Browns were formed in 1926, sponsored by the New Jersey Colored Amusement Company. During their maiden season, the Browns played wherever the team could gain access. But for 1927, Browns management wanted to secure a permanent home field. Although located in virtually all-white Bloomfield, Sprague Field was vacant, serviceable, and only a short trolley ride from the black neighborhoods of central Newark, from which the Browns hoped to draw their fan base.20 So in April, the club assumed the lease for the ballpark.21 The change in tenants was accompanied by a change in the grounds name — at least in African American newspapers. Because the Sprague Electric Company plant been subsumed by its corporate parent and now operated under the name of General Electric, the Browns’ home field would be called General Electric Field in black press game reportage (although the locals and the Bloomfield press would continue to refer to the ballpark as Sprague Field).22

A new club needing to cultivate a following, the Browns had the advantage of home field proximity to Newark’s substantial African American population, access to ample area playing talent, and a local monopoly on black professional baseball — the Newark Stars of the Eastern Colored League having folded midway in the 1926 season. The black press was also supportive, the Pittsburgh Courier heralding Opening Day festivities announced by the Browns: “The management is planning a gala opening day on May 4, with appropriate ceremonies attending the throwing out of the first ball, and a record-breaking throng is expected to crowd old Sprague Field to watch their newest favorites do their stuff.”23

Still, the Browns were handicapped by being an independent club, unaffiliated with either the ECL or the Negro National League. And while the club was able to get games against high-level black teams like the Hilldale Daisies, Homestead Grays, and Brooklyn Royal Giants, Newark was almost invariably the opposition in such contests, submitting to a steady diet of away games against black baseball’s elite. For home engagements at Sprague/General Electric Field, the Browns customarily hosted lesser, non-major league black teams and semipro white clubs.

The Newark Browns remained tenants of Sprague Field for the remainder of the decade and through the 1931 season. Over that time, the club’s perseverance, plus the Depression-driven collapse of the Eastern Colored League, persuaded Hilldale, the Baltimore Black Sox, Pittsburgh Crawfords, and other top black clubs to begin paying visits to the Browns’ home field. Such contests often filled the reduced seating of the grounds to capacity: “… the 2,500 fans that rammed and crammed their way into General Electric Field” were delighted by the Browns’ 9-0 whitewash of Hilldale on August 1, 1931.24 Two days earlier, “the largest crowd that ever packed the stands of General Electric Field” had seen Newark drop a doubleheader to the Baltimore Black Sox.25 The Browns finished a generally successful 1931 season by winning a five-game set against the touring San Juan (Puerto Rico) Stars and then playing a seven-game series against the white Newark Independents for the Newark city championship.26

In early 1932, the Newark Browns took a big step up in stature, gaining admission to the East-West League (EWL), a newly formed Negro Leagues major formed by Homestead Grays club boss Cum Posey.27 An ambitious 132-game split-season schedule was adopted at the circuit’s organizational meeting and widely published in the black press.28 Thereafter, a respectable roster was put together by Browns player-manager John Beckwith, a formidable batsman and reputedly the first player, black or white, to drive a ball over the centerfield fence at Cincinnati’s Redland Field, later known as Crosley Field.29

The Browns opened with a May 1 exhibition game win over the Pennsylvania Red Caps at General Electric Field, but once the regular season started, Newark was snake-bitten. Beginning on the road, the Browns dropped their first four games, committing a staggering 28 fielding errors in the process.30 Once the club got home, incessant rain caused the postponement of their home opener for days. Indeed, the league as a whole was plagued by bad weather throughout the spring, causing the cancellation of a significant number of EWL games. By mid-June, the Newark Browns had managed to play less than half of the 35 games scheduled. And when they did play, the Browns were lousy, posting a 3-14 (.178) record that left the club solidly in last place. More ominously, Newark also had serious money problems. “With the Newark Browns, things have been going very badly,” reported the Pittsburgh Courier, “and because of financial trouble it is doubtful if they will be able to continue.”31 If Newark folded, plans were laid either for the Pittsburgh Crawfords to assume the Browns’ place in the league or for the EWL to drop another team at the July 4 midpoint break in the schedule, and then proceed as a six-club circuit.32

Within days thereafter, such schemes were overtaken by financial realities and the entire East-West League dissolved. The Newark Browns, however, did not discontinue play. Rather, they soldiered on as an independent club that barnstormed the East Coast.33 But once the summer of 1932 ended, the Browns’ time as a professional baseball club was over. Yet Sprague Field’s brief tour of duty as a Negro League venue was sufficient to earn it an entry in the ballparks compendium Green Cathedrals.34

The Newark Browns were the last regular tenant of Sprague Field. Once the Browns disbanded, the ballpark was reduced to hosting the odd local amateur and semipro game. In 1934, the grounds also served as home field for four games of the Newark Dodgers of the newly formed Negro National League II. But Sprague Field was only a backup facility, as the Dodgers and succeeding Negro League clubs like the Newark Eagles preferred the newer and far more commodious Ruppert Stadium (which also had the advantage of being located in Newark proper, not an adjacent white suburb like Bloomfield).

By 1933, however, the Bloomfield Recreation Commission had begun using the Sprague Field grounds as a Monday-through-Friday summer recreation facility dubbed the Floyd Avenue playground.35 Title to a good portion of the real property on which Sprague Field sat had been acquired by the Town of Bloomfield in August 1928.36 The town operated a summer recreation program on the site from that date forward.

Subsequent events related to Sprague Field are shrouded by scant press coverage,37 sketchy documentary evidence, and the passage of time. In all probability, the field’s fencing, grandstand, and bleachers were demolished and removed by 1940. Town fathers were likely ill-disposed toward absorbing the costs of maintaining a little-used wooden ballpark exposed to the elements. Today, the site of long-gone Sprague Field remains the site of a Bloomfield playground that fosters the aspirations of the community’s youngest ballplayers. And that is not a bad legacy.

Acknowledgments

This article was originally published in the December 2018 issue of Palaces of the Fans, the newsletter of SABR’s Ballparks Committee. This version was edited by Rory Costello and fact-checked by Warren Corbett.

Sources

The primary sources for the narrative above are contemporaneous reportage in The (Bloomfield, NJ) Independent Press and Pittsburgh Courier, and Sam C. Pierson, Thumbing the Pages of Baseball History in Bloomfield (Bloomfield, NJ: The Independent Press, 1939). Unless otherwise noted, information pertaining to Negro Leagues baseball has been taken from The Negro Leagues Book, Dick Clark and Larry Lester, eds. (Cleveland: SABR, 1994).

Notes

1 The Sprague Field profiled herein is not to be confused with the later Sprague Field that serves as home grounds for Montclair (NJ) University athletic teams.

2 Named for electrical engineer-inventor Frank J. Sprague (1857-1934), Sprague Electric Company designed and manufactured railway switches and other apparatus crucial to the development of urban mass transit, and had been a presence in Bloomfield since 1884. Later, the plant segued into the production of radio components and other electrical devices. Acquired by General Electric in 1902, the company retained the name Sprague Electric into the 1920s.

3 As per “Sprague Electric Base Ball Team,” The (Bloomfield, NJ) Independent Press, April 4, 1919. The cost of fixing up the diamond was subsequently estimated at $2,000.

4 Per Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Walker & Company, 2d ed., 2006), 21. The smallish Sprague Field dimensions were the rough equivalent of other contemporary ballparks, including Redland (later Crosley) Field — LF: 328; CF: 387; RF: 366 in 1938. Or today, Oriole Park at Camden Yards — LF: 333; CF: 400; RF: 318.

5 See “Sprague Works Field Day Was a Great Success,” The Independent Press, September 17, 1920.

6 Per “Sprague Team Opens Baseball Season Here,” The Independent Press, May 1, 1919.

7 According to Sam C. Pierson, Thumbing the Pages of Baseball History in Bloomfield (Bloomfield, New Jersey: The Independent Press, 1939), 78. For decades, Pierson was the hometown weekly’s sports reporter.

8 Per “Bloomfield Was Stronghold of Baseball in Early Days,” The Independent Press, April 12, 1954. See also, Pierson, 70.

9 Ibid. See also, Pierson, 71.

10 Ferguson posted a 61-85 (.418) record in a 10-season major league career that ended in 1929.

11 Per The Independent Press, April 12, 1954.

12 Per Pierson, 74-75. The 1954 retrospective cited in endnote 8 placed the Bloomfield Elks club record for the 1921-1926 seasons at an even better 124-53 (.701).

13 See “Newark School Board To Oust Bears from Oval,” Jersey (Jersey City) Journal, June 6, 1924.

14 Newark Evening News editorial re-printed in The Independent Press, March 26, 1926.

15 “Newark Bears to Play on Sprague Field,” The Independent Press, March 26, 1926, and Edward H. Foegel, “Newark Fans Go Limit to Get Their Baseball,” The Sporting News, April 8, 1926.

16 See “9,000 See Bears Beat Phillies, 9-7,” New York Times, April 11, 1926.

17 Per Howard Freedman, “Evening Muse,” Newark Evening News, April 15, 1926.

18 After the fire, the Elks occasionally used Sprague Field for matches against non-draws like the Newark Hebrew Club. See “Hebrew Club Finds Antlers Easy,” (Newark) Jewish Chronicle, June 4, 1926.

19 As recollected in The Independent Press, April 12, 1954. See also, Pierson, 74-75.

20 As elsewhere in the North, 1920s New Jersey was an apartheid-like state, with few racially-mixed neighborhoods. Bloomfield and the adjoining neighborhoods of East Orange and north ward Newark had hardly any black residents, but Sprague Field was within short walking distance of a stop of a Bloomfield Avenue trolley line that originated in the African American precincts of downtown Newark.

21 Per “NJ Browns To Be Classy,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 1927.

22 Contemporary Negro Leagues websites like Seamheads.com list the home grounds of the 1932 Newark Browns (and 1934 Newark Dodgers) as General Electric Field. That name, however, never gained much local traction. To Bloomfield natives, the name of the ballpark was always Sprague Field.

23 Pittsburgh Courier, April 19, 1927.

24 Per “Newark Defeats Hilldale,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 15, 1931.

25 See “Black Sox Top Newark in Twin Bill,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 1, 1931.

26 As per the Pittsburgh Courier, October 3, 1931. The Browns won the series against the San Juan Stars. The outcome of the Newark city championship was undiscovered by the writer.

27 The other clubs admitted to the EWL were the Homestead Grays, Hilldale (Philadelphia) Giants, Baltimore Black Sox, (New York) Cuban Stars East, Detroit Wolves, Cleveland Hornets, and Washington Pilots.

28 See e.g., Pittsburgh Courier, April 30, 1932, and (Los Angeles) California Eagle, May 6, 1932.

29 According to sports columnist Louis E. Dial in the New York Age, March 12, 1932.

30 Sportswriter W. Rollo Wilson found such fielding ineptitude “almost impossible” to comprehend. Pittsburgh Courier, May 28, 1932.

31 Per “May Cut to 6 Clubs,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 25, 1932.

32 Ibid.

33 Per “Forgotten Heroes: John Beckwith,” Dr. Leyton Revel and Luis Munoz, Center for Negro League Baseball Research, 2014, 14.

34 See endnote 4 for full title and publication data.

35 The first discovered report of activity at the Floyd Avenue playground appeared in “Bloomfield Playgrounds Now at Height of Summer Activity,” The Independent Press, July 21, 1933.

36 Per Deed dated August 10, 1928. Forty years later, Bloomfield acquired formal title to the remainder of the property. Many thanks to Andrea Schneider, confidential assistant to the Bloomfield Town Administrator, for supplying copies of the now-Felton Field property deeds to the writer.

37 The last discovered press mention of Sprague Field states that the site of the former ballpark was acquired by Westinghouse for conversion into an employee parking lot. See “Town Parking,” The Independent Press, August 8, 1957. But the article’s unidentified author misapprehended where Sprague Field was located (some distance to the south of the Westinghouse parking lot), and by 1957, the old Sprague Field grounds had long been converted into a neighborhood playground then called Floyd Field.