Swayne Field (Toledo, OH)

This article was written by John R. Husman

In 1955 Toledo, Ohio, suffered the double indignity of losing both its baseball team and its baseball park. The departure of the Toledo Sox and the fall of Swayne Field were unexpected, sudden, and brutally final, and the effects were long-lasting. As the 1955 baseball season drew to a close, no one in Toledo suspected the coming losses.

Baseball in Toledo had been on shaky footing since World War II. Under the ownership of the St. Louis Browns, the Toledo Mud Hens had their last winning season in 1944, and the Browns sold the franchise to the Detroit Tigers after the 1948 season. The Tigers operated the team for three seasons, leaving after the 1951 campaign and not having had a winner either. Danny Menendez brought an independent team to Swayne Field for the 1952 season, but transferred them to Charleston, West Virginia, in June, leaving Swayne Field empty for the remainder of the summer.

Just before the opening of the 1953 season, fortune smiled on Toledo. The Boston Braves moved to Milwaukee in the first shift of a major-league franchise in more than 50 years. The Braves displaced the American Association Brewers, who, in turn, landed in Toledo and began a rags-to-riches saga. The Brewers, who had won the pennant in 1952, were renamed the Toledo Sox and gave the city its first pennant since 1927. Toledo’s new team set an attendance record in 1953 as 343,614 poured through the Swayne Field turnstiles. The Sox were the top farm club of the Braves, who were building the team that would win the World Series four years later. Toledo’s baseball future seemed bright. The Sox fell back in both the standings and the gate in 1954 and 1955, but were competitive and still drew good crowds. Inexplicably, the parent Milwaukee club moved its Toledo operation to Wichita after the 1955 season. Just days later, Swayne Field was sold to the Kroger Company, which very quickly transformed the site into a shopping center. Swayne Field had been Toledo’s landmark baseball park and outdoor sports center for 46 years, but seemingly overnight it was gone.

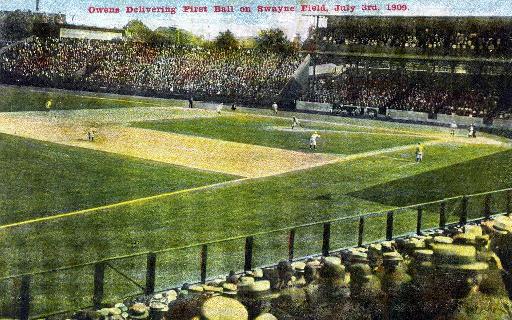

Swayne Field was privately financed and as fine and modern a baseball park as there was in America when it rose out of an old fairgrounds in west Toledo. It was the largest baseball playing field in the world. Construction of Swayne Field began on March 6, 1909. Less than four months later, baseball was played there. The concrete and steel plant was the apparent brainchild and investment of William R. Armour and Noah H. Swayne, Jr.

Professional baseball had been played in Toledo since 1883. The game floundered in the early years. Changes of ownership, playing grounds, league affiliations, and even nicknames were the norm for 19th-century Toledo baseball. Some years a team was not fielded at all or the season was shortened. Businessman Charles J. Strobel brought the stability necessary for Toledo baseball to be a legitimate proposition. He bought the Toledo team in 1896. During his tenure of 11 years he established a popular downtown location and the Mud Hens nickname, entered Toledo in the competitive American Association, and won a couple of championships along the way. During Strobel’s time baseball in Toledo matured and became firmly established. A constant through these early years was Swayne, who was a board member and instrumental since the early days.

William R. Armour entered the scene by coming from Detroit and purchasing, on behalf of Charles Somers of Cleveland, the Toledo club. Managing on the field as well as running the business, he finished a close second his first season of 1907. The following year the team finished fourth, but the business was healthy. Armour knew his Armory Park was inadequate in two respects: seating capacity and the size of the playing field. He set about to remedy both problems and found a ready ally in his board of directors chairman, Noah H. Swayne. Armour and Swayne conspired for a new park during the 1908 season. The idea may have been born as Armour sat in Swayne’s box during a game at Swayne Field’s predecessor, Armory Park. “They noted the crowd that stood on every available foot of the park, outside the playing field. ‘Billy,’ said Mr. Swayne, ‘we’ve got to do something about this pretty soon. This place is bursting out at the seams. We must have a bigger plant.’ ‘I know it,’ said Armour. ‘We have to turn people away every Saturday. But I don’t know where we can go. This place is central. That’s one reason we have such crowds. If we go out in the country, what will we do for transportation?’ ” The idea was born along with the realization that moving to what were then the suburbs would be a radical move, albeit one that many other cities had already made.

Swayne and Armour set about the business of building the new plant. And they did it quickly. Nearly completed plans, “the latest that baseball architects can make,” were first announced in the Toledo Blade on January 25, 1909. For his part, Swayne purchased the land, closing the deal on January 21 with the Woolson Spice Company of New York City to purchase property at the northwest corner of Monroe Street and Detroit Avenue for $47,500. In turn he leased the tract to Armour’s Toledo Exhibition Company, operator of the Mud Hens, on March 17. Popular opinion has held that Swayne donated the property. Not so. Records at the Lucas County Recorder’s office show that terms of the lease called for annual payments to Swayne of $1,902 per year. The lease was perpetual and contained a clause that provided the club the option of buying the property after ten years for $31,700. Swayne was assured the return of his investment, but the option was never exercised. The lease also contained provisions for Swayne to be personally accommodated at the new park. It specified that the club “reserve and set aside … a box of sufficient floor space to accommodate six chairs comfortably … and to provide tickets or passes … not to exceed six in number,” for the lessor.

Swayne and Armour set about the business of building the new plant. And they did it quickly. Nearly completed plans, “the latest that baseball architects can make,” were first announced in the Toledo Blade on January 25, 1909. For his part, Swayne purchased the land, closing the deal on January 21 with the Woolson Spice Company of New York City to purchase property at the northwest corner of Monroe Street and Detroit Avenue for $47,500. In turn he leased the tract to Armour’s Toledo Exhibition Company, operator of the Mud Hens, on March 17. Popular opinion has held that Swayne donated the property. Not so. Records at the Lucas County Recorder’s office show that terms of the lease called for annual payments to Swayne of $1,902 per year. The lease was perpetual and contained a clause that provided the club the option of buying the property after ten years for $31,700. Swayne was assured the return of his investment, but the option was never exercised. The lease also contained provisions for Swayne to be personally accommodated at the new park. It specified that the club “reserve and set aside … a box of sufficient floor space to accommodate six chairs comfortably … and to provide tickets or passes … not to exceed six in number,” for the lessor.

Construction was begun on March 6, 1909. Plans called for a first-class plant, Armour promising to spare no expense. Backed by Somers, he invested about $125,000 for grandstands and bleachers, clubhouses, ticket offices, a concrete fence and the playing field itself. Construction of the grandstands was of steel and reinforced concrete, and was said to be fireproof. The facilities rivaled those of Philadelphia’s Shibe Park, the major leagues’ first concrete and steel ballpark, which also opened in 1909. It was not the first such park in Toledo’s own league, the American Association, however, as Columbus’s Neil Park had been in use since 1905 and was a huge success. The fence surrounding Swayne’s playing field was also of innovative design, being the only one in the country made of concrete. The fence was 12 feet high, and team president Armour promised to have it decked with vines and flowers “to add to the beauty of the neighborhood.” The Blade identified its true purpose, however: “It will be tough on the small boys, for it will be almost proof against climbing over, and no knives will penetrate it.” The left-field portion of that wall still stood early in the 21st century.

This was an era when ballpark design was driven by the desire to provide an ample expanse for the outfielders to display their skill in chasing down long drives. The playing field was the largest in the world. It would seem all the larger when compared with its predecessor, Armory Park, which was extremely small. The playing area for Swayne was more than double that of Armory. Dimensions for the new park were 326 feet in right field, 380 feet in left and just over 500 feet in center field. The distance from home plate to the grandstand was 72 feet, more than 40 feet greater than at Armory Park, providing a much greater foul territory and prompting the Blade to comment, “Capture of foul balls, which was almost an impossibility at Armory, because the spheres went over the stand or in the right field bleachers, will add interest to the games, too.” On the overall expanse the Blade said, “But with this big place to play there ought to be some swell clouting. Another chance for swell playing will be on drives that get away from the outfielders. If the ball ever gets by center field and rolls that 550 (actually 505) to the fence it will be good-bye to chances to stopping the man who hit it, for it will be a sure home run.” The seating capacity of the new plant was 11,900 (allowing two feet per person in the bleachers) versus Armory’s probable maximum of 4,500. .

Construction was speeded up by the use of double crews, from “dawn to dark and dusk to dawn” aided by arc lamps. Competition for building tradesmen was keen as Toledo was in the midst of a building boom in 1909 with the Art Museum, the main Post Office, the Nearing Building and a General Electric factory and others under construction. Nonetheless, Swayne Field was completed with time to spare for its planned debut with archrival Columbus on July 3.

Transportation was a concern as the location was considered “suburban.” Street-car service, however, was excellent as the Long and Short Belt cars ran directly to the park and the Bancroft line discharged passengers two blocks away. Improvements were proposed: double-tracking Monroe Street and installing a switch so that Rail-Light, the traction company, could store up to 60 cars at its adjacent property to handle the rush after the game. The riding time by streetcar from downtown was 16 minutes. Pavements for autos were described as “the best,” and parking inside the confines of the park was provided for automobiles, bicycles, and other vehicles.

Notable among the neighborhood businesses that could benefit from the new park’s presence were the “liquor interests,” that is, saloon operators and breweries. Petitions were circulated in the neighborhood in an effort to make “wet” districts “dry” and vice-versa. Among the principals were former Sheriff Sereno Chambers, who sought to open a saloon to dispense Huebner-Toledo merger beer at Detroit Avenue and Monroe Street, opposite Swayne Field. A. Morris Loenshal was their advocate. He had lobbied residents just a few years earlier to make the same area dry. He was then successful in having the law invoked that forced saloonkeepers who sold beer from the vats of rival brewers out of business. Advocates for the “drys” were headed by Rev. J. Sanford, superintendent of the Toledo District Anti-Saloon League. Initially liquor was not sold at Swayne Field, as it was in a “dry” district.

The opening day was all that was promised. The press had been touting the event for weeks. The opening had been timed so that Columbus would be in town. Armour had given up his field manager duties for 1909 in order to concentrate on finances, construction, and most importantly purchasing the players who would bring Toledo a championship team. He had promised that there would be no finer team in the American Association, but at this midpoint of the season that was not case. Toledo was in last place. Armour made a change of manager as well, naming Mud Hens player Socks Seybold to replace Fred Abbott beginning with the inaugural game in Swayne.

There were ceremonies and guests. The blue and white Toledo baseball flag, 36 feet long, was raised on an 80-foot staff while heads were bared and a band played. Mayor Brand Whitlock delivered the dedication address. The fans pressed in, but did not fill every available seat. There were 1,000 upper-deck grandstand seats at a dollar, 1,596 lower grandstand seats at 75 cents, another 3,304 at 50 cents, and 6,000 bleacher spaces at a quarter each. The game itself was one of the most exciting on record, but the Hens came out on the short end of a 12-11 score in 18 innings. The “double” contest was played in 3 hours and 35 minutes and enjoyed by 9,350, the largest crowd ever to witness a baseball game in Toledo up to then. The Hens’ right-handed-hitting Charley Hickman surprised all by striking a ball over the fence in right field for a home run. In this, the day of the dead ball, many had wondered if a ball would ever be hit over any of Swayne’s fences.

Swayne Field would go on to a long life. During the course of its 47 years (43 full and three partial seasons) it was home of professional baseball in Toledo. But it showcased other events as well. Amateur baseball was often played there. Major-league exhibitions, football, and Negro League baseball were a part of the scene as well. Golf demonstrations, automobile daredevil shows and other nonbaseball entertainment events were used to attract people over the years.

It was at Swayne that Toledo earned its reputation as a place where many talented individuals performed, but teams usually fared poorly. During the Swayne Field years, only two championships were won, in 1927 and 1953. During that 1953 season the all-time Toledo record 343,614 (since greatly surpassed at Fifth Third Field) watched the Sox play (the largest single-game crowd was 17,500 on Opening Day in 1916). The 1927 team went on to defeat Buffalo in the Junior World Series under the tutelage of Casey Stengel.

Changes, additions, and improvements were made to the facility over the years. An early improvement was the use of a canvas tarpaulin, purchased from the M.I. Wilcox Company in 1910, to protect the infield from rain. The year after the pennant-winning season of 1927, bleachers were installed in center field, increasing the seating capacity to 15,000. The first game under the lights was played at Swayne on June 23, 1933, two years before the first major-league night game. An inner fence installed in 1945 made the home-run distance to left and center fields more reasonable. A large gate was made in the new wall to allow storage of the batting cage between the fences during games. (Tommy Beard, who was the batboy in 1953, tells of outfielder Luis Marquez giving him his glove to catch pregame fly balls while he ducked through the gate and had a smoke between the fences.) Swayne Field did not have a warning track until 1949, when Fred Galliers, a local businessman and Toledo baseball club booster, donated one because of his concern for outfielders crashing into the wall. There were numerous facelifts, usually associated with ownership changes. On the downside, the upper-deck grandstand was deemed unsafe and closed in 1939.

Sportscaster Frank Gillhooley spent a lot of time at Swayne Field. Beginning in 1937 he worked as a clubhouse boy for three years, followed by two more as batboy. He returned as the radio voice for the Sox in 1953, and was still behind the microphone for Mud Hens games when the team left in 1955. He didn’t hesitate when asked about his most vivid memory of Swayne Field. Mickey Mantle. He was there the night in 1951 when Mantle was in town with the Kansas City Blues. Mantle hit for the cycle with two home runs. His single came on a ninth-inning bunt and after he was ordered, as a crowd-pleasing gesture, by his manager George Selkirk, to swing away on a 3-0 count. Marlin Stuart pitched a perfect game there for the Hens in 1950. Olympian Jim Thorpe once hit three home runs in a game. Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig hit home runs on to Detroit Avenue during a matchup of World Series and Junior World Series champions at Swayne in 1928. Cy Young was there in 1947 as a part of the Toledo Old Timers Field Day. An old man, he toed the rubber at Swayne nonetheless. Sometimes nonplayers played. Champion golfer Byron Nelson, who was the head pro at the Inverness Club in Toledo in the 1940s, was in right field for the Hens in a 1942 exhibition against the parent St. Louis Browns.

Other memories remain. The Edison smokestack with the words Heat, Light, and Power, and the coal piles rising beyond left field. Red Man Tobacco lettered on nearby buildings. Fans exiting across the playing field and out on to Detroit Avenue through a gate in the right-field fence. Ropes restraining overflow crowds around the outfield. Briggs green was everywhere after the Detroit Tigers bought the club in 1948. The gates were opened late in the game, allowing free admission to anyone, and a free pass could be had for the return of a ball.

Other memories remain. The Edison smokestack with the words Heat, Light, and Power, and the coal piles rising beyond left field. Red Man Tobacco lettered on nearby buildings. Fans exiting across the playing field and out on to Detroit Avenue through a gate in the right-field fence. Ropes restraining overflow crowds around the outfield. Briggs green was everywhere after the Detroit Tigers bought the club in 1948. The gates were opened late in the game, allowing free admission to anyone, and a free pass could be had for the return of a ball.

Noah Swayne died in his vacation home in Quebec on October 21, 1922. The Toledo press expressed surprise. Swayne may have known that death was imminent as he sold the Swayne Field property to Edgar Feeley of New York just five days before he died. Feeley in turn sold it to the Detroit Development Company in 1926. Bankruptcy befell the operation in 1931 and Toledo realtor Allie E. Reuben was appointed by the courts as receiver. Reuben took ownership himself in 1933 as the Swayne Field Company. With court approval, he purchased “certain miscellaneous assets” for one dollar. Lucas County records indicate that Reuben sold the property to the Kroger Company for one dollar. It was reported that the asking price was about $500,000, however.

More innings were played at Swayne Field on its last day, September 5, 1955, than the 18 played on its first. This time 21 innings were played, but it took two games to do it. Toledo’s Sox lost to the Indianapolis Indians 3-2 in the first game, and won the nightcap 2-1 in 12 innings when future major-league shortstop Felix Mantilla scored the winning and last run on a squeeze play. A scant crowd of 1,748 witnessed the well-played finale. Nobody there knew it was the old park’s last hurrah.

Photo Credits

1. John R. Husman

2. Toledo Blade

3. Toledo-Lucas County Public Library

Sources

Husman, John R. Baseball In Toledo, Arcadia Publishing, 2003.

Lin Weber, Ralph Elliott. The Toledo Baseball Guide of the Mud Hens 1883-1943, Baseball Research Bureau, 1944.

Toledo Bee

Toledo Blade

Toledo News-Bee

Toledo Times