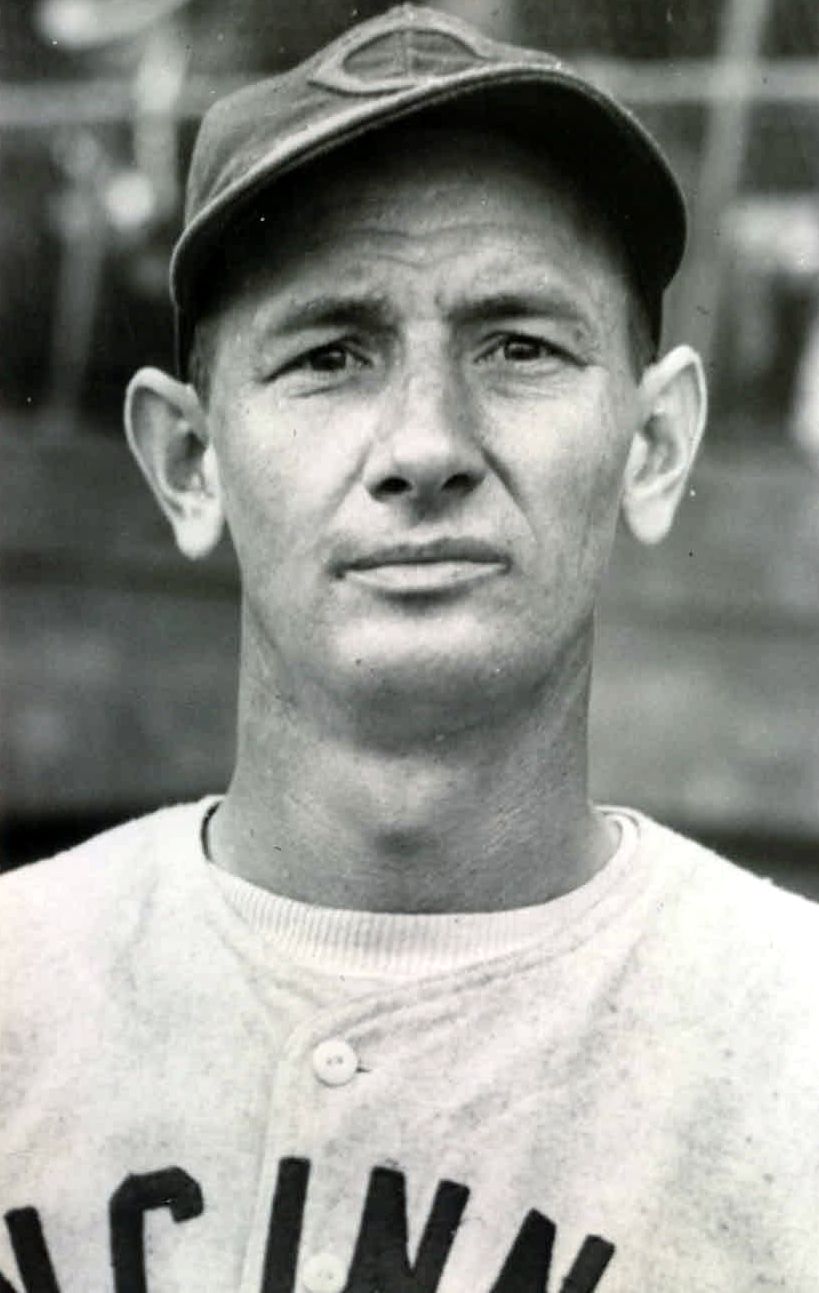

Lefty Guise

As of the end of the 2014 season, 18,400 players are recognized by Baseball-Reference as having played in the major leagues. Of this group 595, or a little over 3 percent, share an interesting distinction: They played their first major-league game for a team that won the World Series that year. Eleven of this group went on to Hall of Fame careers (Joe Sewell, Travis Jackson, Lou Gehrig, Bill Dickey, Joe DiMaggio, Joe Gordon, Phil Rizzuto, Satchel Paige, Whitey Ford, Mickey Mantle, and Sandy Koufax). A few more had substantial careers with multiple All-Star appearances, and some of the more recent players may yet make the Hall, for example Carlos Delgado and Jeff Kent.

As of the end of the 2014 season, 18,400 players are recognized by Baseball-Reference as having played in the major leagues. Of this group 595, or a little over 3 percent, share an interesting distinction: They played their first major-league game for a team that won the World Series that year. Eleven of this group went on to Hall of Fame careers (Joe Sewell, Travis Jackson, Lou Gehrig, Bill Dickey, Joe DiMaggio, Joe Gordon, Phil Rizzuto, Satchel Paige, Whitey Ford, Mickey Mantle, and Sandy Koufax). A few more had substantial careers with multiple All-Star appearances, and some of the more recent players may yet make the Hall, for example Carlos Delgado and Jeff Kent.

Of the rest, most made their debuts in April (and were gone by the time the postseason rolled around), or in the last few days of the season (when the team’s playoff position was already clinched and there was no possibility of inclusion on the postseason roster). And most of these came back in a subsequent season or seasons and played on teams that didn’t win the World Series.

For a select few, however, their introduction to the majors came in the heat of a pennant race that culminated in a World Series win. And for an even smaller group, that pennant race was the sum total of their major-league experience – they never made it back to the majors again.

Lefty Guise was part of that unusual group. And not only did he join the 1940 Cincinnati Reds for their stretch run to what would be their only world championship between their controversial victory in 1919 and the Big Red Machine’s 1975 triumph, he made enough of an impression that his teammates voted him a partial share of their World Series money even though he pitched in only two games during the regular season and sat on the bench for the entire Series. Along the way Guise retired the first two batters he faced in the majors, both future Hall of Famers; got his only major-league base hit off another future Hall of Famer; pitched 7? innings while allowing only one earned run; and even got a mention in a 1950s book, Baseball’s Famous Pitchers.

Witt Orison “Lefty” Guise was born in the tiny town of Driggs in northwest Arkansas, on September 18, 1908, and died about 100 miles away in a Little Rock hospital nearly 60 years later. In between he lived a life as colorful and unique as his name.

Witt’s father was a country doctor who moved to Florida to try his hand at truck farming. He and almost all the rest of the family returned to Arkansas within a few years, but Witt stayed on in Pahokee after graduating from high school and enrolled in the University of Florida, where he pitched in 1929 and 1930. When that school’s 1930 season ended, he signed a contract with the Yankees organization and headed north to pitch for Hazleton in the Class B New York-Pennsylvania League, recording seven wins and six losses, and then finished the year by throwing a few innings for Jersey City in the International League. In 1931 he pitched for the Albany Senators in the Class A Eastern League and posted indifferent results: a 6-12 record and a 4.05 ERA. Playing behind him at shortstop was the future Yankees stalwart and later Dartmouth athletic director Red Rolfe. They saw Babe Ruth’s two home runs lead the Yankees to an 8-5 exhibition win over their Albany farm team that year.

During the offseason that followed, Witt was pulling awkwardly on an oar while fishing in Florida, and “I could feel the muscles in my shoulder coming apart. When I reported for baseball [the] next spring, I couldn’t toss an apple into a barrel.”1 That was the end of his Organized Baseball career for seven seasons, but not the end of his hopes to pitch in the majors. Experimenting with a knuckleball and a screwball, Guise gradually returned to pitching for semipro clubs; looking back on those years, he said, “I never learned to pitch until I hurt my arm.”2

By 1935 Guise was pitching for the Concord Weavers, a top-notch mill team competing in the semipro Carolina Textile League in west-central North Carolina; such teams often offered ballplayers employment at the mill in addition to a place to play ball. The next year the Weavers had joined the independent “outlaw” Carolina League. (The Carolina League would prove to be the longest-lived direct challenge to Organized Baseball’s reserve clause, enduring longer than either the Players League or the Federal League.) Guise had already become a fan favorite in 1935, posting a 9-5 record; in the three subsequent years he recorded 35 wins and 19 losses. In their book The Independent Carolina Baseball League, 1936-1938, Hank Utley and Scott Verner wrote, “He had the demeanor of an Arkansas hillbilly, and he knew how to make a baseball dance. Some accused him of throwing spitballs, others of throwing a cut, roughed-up, or ‘doctored’ ball – one that had been altered illegally to make its flight path more difficult to hit. He called his wobbly pitch a ‘sidearm knuckleball.’ He had the habit, with two out and two strikes on the batter, of throwing that slow, dancing ‘sidearm knuckleball’ toward home plate and, in the same motion, beginning to walk toward the Weavers bench on the first-base side, knowing the batter would watch it go by or swing at it in vain. The home fans loved this show of bravado; opposing hitters despised it.”3

Despite continual turnover, the Carolina League managed to stay together for three years before the recovering economy, Organized Baseball’s threats, and the league’s own internal bickering brought it to an end. In 1939 Witt signed with Lenoir of the Class D Tar Heel State League. Not only did he have an outstanding year pitching for Lenoir, he was named manager of the team halfway through the season after his predecessor resigned. His pitching record that season was 15-7, with a 2.82 ERA and a five-inning no-hitter ended by rain.

The 1940 season was even better. By that time Lenoir was a Cincinnati Reds affiliate, and Lefty was promoted to their Class B South Atlantic League team at Columbia, South Carolina, to start the season. He entered the season opener against Augusta with two out in the bottom of the ninth and the tying run on third, and retired the only batter he faced.4 Notwithstanding this auspicious debut, team officials put him on the “suspended list” for nearly a month soon afterward, a stratagem that allowed them to look at several younger pitching prospects. After being reinstated as a reliever, Guise eventually became a starter, with spectacular results. He pitched two one-hitters, had a stretch of 59 innings in which he allowed only two runs, and was the winning pitcher in the league’s all-star game.5 For the season he compiled 13 wins, 6 losses, and a 2.06 ERA. Alderman Duncan, an Associated Press writer in Columbia, sent out a puff piece on Witt in late July highlighting his accomplishments and his major-league aspirations: “Lefty Witt Guise wants to try his tricky delivery on the big league boys. Batters down here in the South Atlantic loop would like that fine – they’re sick of trying to hit his goofy glider. … He uses a sidearm delivery and a tricky change of pace. His control, flighty at first, is good now. … Guise realizes his age is against him, but he wants mightily to pitch big league baseball. He feels he has seven or eight years of good pitching left.”6 Sure enough, the Reds called him up on August 26.

The Cincinnati organization, led by general manager (and eventual National League president) Warren Giles, had come a long way back by 1940. The storied franchise, associated with baseball’s first “national” team, had managed only a single first-place finish in the National League’s first 49 years: that was the 1919 team that upset the White Sox to win the World Series, only to have its victory tainted by widespread accusations that Chicago players had thrown the games. From 1927 through 1937 the Reds never finished better than fifth, landing in the cellar in 1937 for the fifth time in seven years. But they had improved by 26 games in 1938, finishing fourth, then improved by another 15 games in 1939 to win the pennant. After being swept by the mighty Yankees in that series, they came back stronger than ever in 1940; when Guise was called up they led the second-place Dodgers by 7½ games. They were suffering through a difficult August, however, needing to win two of their last three just to break even for the month.

August had been a difficult month for the Reds in a far more significant way. On August 3 Willard Hershberger, Cincinnati’s pensive and self-critical backup catcher, took his own life in his Boston hotel room. It remains the major leagues’ only in-season suicide by an active player, and it was a devastating blow to his teammates.

On the field it was clear that as the season wound down the Cincinnati bullpen needed help. Beyond “Fireman” Joe Beggs, the bullpen anchor, there wasn’t much available. Bringing Guise up was taking out a logical insurance policy.

The first call Guise received was in the September 3 home game against the Cardinals, after fellow rookie John Hutchings was pulled for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the second with St. Louis leading 2-0. First to face Guise was Enos Slaughter, the North Carolina native who was such a prototypical hillbilly that his nickname was “Country.” Guise won the first skirmish in the battle of country boys as Slaughter watched strike three go by; it would prove to be Witt’s only major-league strikeout. Johnny Mize came up next – another country boy, from the piney hills of north Georgia; that season his 43 homers, 137 RBIs and 368 total bases would lead the league in all three categories and earn him second place in the MVP voting. Mize grounded out to short. Having retired these two future Hall of Famers in his first big-league outing, Guise could perhaps be forgiven for walking Ernie Koy before retiring Don Padgett on a fly ball to center field.

After Cincinnati failed to score in the bottom of the third, Witt went back to work. Joe Orengo, just beginning a career as a journeyman infielder best remembered as the guy who gave Mize his “Big Cat” nickname, grounded out. Rookie Marty Marion collected the first hit off Guise, a liner to center. Starting pitcher Bill McGee sacrificed Marion to second, and Jimmy Brown grounded out to short.

Jimmy Ripple’s two-run homer tied it up in the bottom of the fourth, and now Lefty was the pitcher of record. Shortstop Billy Myers retired Terry Moore, and Pepper Martin batted for Slaughter and grounded out. Mize clouted a triple to center field, Koy was hit by a pitch, and Mickey Owen pinch-hit for Padgett, lofting one to second baseman Lonny Frey for out number three.

The bottom of the fifth brought Guise to the plate for the first time, and he grounded out, Mize to McGee covering first. The next two batters were retired, and Lefty returned to the mound for the sixth, yielding a leadoff single to Orengo, but inducing Marion to fly out and McGee to hit into a double play. A two-out walk was all the offense the Reds could manage in the bottom of the sixth. The top of the seventh began innocently enough, with Brown fouling out to catcher Jimmie Wilson. But then Moore, Martin, and Mize recorded consecutive singles to load the bases, and Koy finished his third consecutive at-bat without putting a ball in play by drawing a walk that forced home the go-ahead run. With that, Guise was done for the day; Joe Beggs, finishing up what would be his finest season (12 wins, 3 losses, 2.00 ERA), took over, inducing Owen to bounce into an inning-ending double play. Cincy rallied for single runs in the seventh and eighth innings for a 4-3 win to extend their lead over the Dodgers to eight games.

Guise’s only other appearance came 10 days later, on Friday, September 13, at the Polo Grounds. By this time the Cincinnati lead was 8½ games, and the pennant all but assured. With a 2-0 lead in the bottom of the third, Reds starter Johnny Vander Meer, back from months of rehabbing at Indianapolis, suddenly couldn’t find the plate, walking in a run with his third free pass in a four-batter stretch. Guise took the mound with one out and the bases loaded against Frank Demaree. Demaree lined one to third baseman Billy Werber, who threw to second, doubling up Bob Seeds.

Carl Hubbell was pitching for the Giants, at age 37 near the tag-end of his magnificent career but still a formidable opponent. In the top of the fourth, King Carl had already given up Cincinnati’s third run when Lefty came to the plate. Guise stroked a clean single to center before Werber struck out to end the inning. Babe Young walked in the bottom of the fourth, but first baseman Frank McCormick turned Harry Danning’s grounder into a 3-6-3 double play, and Mel Ott grounded out to second. After a three-up, three-down top of the fifth, Mickey Witek grounded out, Burgess Whitehead walked, and Hubbell’s shot to McCormick started the Reds’ third double play in three innings. The Reds added another run in the sixth and had Ernie Lombardi on third when Guise ended the inning, and his major-league offensive career, by grounding out short to first.

In Lefty’s final inning on the mound, Seeds singled, Jo-Jo Moore flied out, Demaree singled Seeds to second, and Young flied out. Billy Werber couldn’t handle Danning’s liner, and Seeds scored. Ott’s walk loaded the bases. Once again Joe Beggs came to Guise’s and Cincinnati’s aid, retiring Witek to end the inning and preserve the lead. Another Cincinnati run in the seventh made the final 5-2. Beggs was awarded the win, but in today’s environment it might well have gone to Guise with Beggs getting a save; each pitched 3? effective innings. (In an interview during World War II, Guise managed to simplify it this way: “I was warming a bench during the series, but I had pitched one game for the team during the season, and won it.”7)

The Reds eventually won the pennant by 12 games over the Dodgers, securing their 100th win of the season in their final game. They had a remarkable 23-8 record in September, and were 25-9 after Guise joined them in late August.

All told, Lefty faced 20 different batters (including four future Hall of Famers) in his major-league career, in a total of 34 plate appearances. He recorded only the single strikeout, walked five and hit a batter, and gave up eight hits in 7? innings. Four double plays helped him out; he gave up two runs, one earned, for an ERA of 1.17.

Guise’s base hit off Hubbell led to the mention in Baseball’s Famous Pitchers, a 1954 book written by Ira Smith, who asserted that Guise was so thrilled by getting a hit off one of the greatest pitchers ever that he decided to celebrate by taking a dollar bill, putting it into an envelope, and mailing it to the Salvation Army.8

Witt made the most of his Arkansas roots throughout his career, realizing early on that sportswriters and fans responded well to the country-boy persona even when it didn’t square with the reality of a higher level of sophistication and education. From the time he re-entered Organized Baseball, Guise stood out from his teammates because of his age, his hillbilly aura, and his unorthodox pitches. This made him good copy, and brought him frequent notice in the media of the day. Abe Fennell of Columbia’s The State newspaper took to calling him “The Old Lefthander,” and by the time Guise made the majors with the Reds, Lefty and the writers covering him both enthusiastically embraced the hillbilly angle.

During 1941 spring training, Pete Norton of the Tampa Tribune noted that “Witt Guise, the tall, drawling Arkansas lefthander, is the nearest thing to a colorful ball player we have spotted in the Grapefruit League since Lefty Gomez kept the pressbox in stitches some years ago when he broke with the Yankees.” He quoted Witt’s answer to a question about his late entry into the majors: “About eight years ago someone told me that if I developed a knuckle ball, I might become another Carl Hubbell. It’s taken me eight years to develop anything that looks like a knuckler. I was afraid to show up in a major league uniform until I had something besides a fast ball, perfect control and a good change of pace.” Norton also cited Lou Smith of the Cincinnati Enquirer who said Guise had told him that when he headed home to Magazine, Arkansas, after the 1940 World Series victory, he stopped just outside town to take off his shoes, explaining that “I didn’t want the home folks to think I was getting high hat.” Finally Norton quoted Gabe Paul, then the Reds’ traveling secretary and eventually their general manager: “I was looking through the Reds’ roster yesterday in the club office at the Floridan hotel, when Guise walked in and asked me if he could get ‘one of them thar catalogs that tell about the ball club.’”9

Whitney Martin of the Associated Press put it this way: “He’s a long, loose Arkansan vaguely resembling Lon Warneke, and so lean the chaw of tobacco in his cheek sticks out like an orange in a Christmas stocking. … Guise has adopted sort of a professional hillbilly air, as that seems to be what’s expected. If the folks want to hear of how he had to stomp on the pumpkin vines because they were racing over and threatening to strangle grandpaw, that’s what he’ll tell them. Always accommodating. But he’s anything but a hillbilly. His dad is a physician, and Witt himself went to the University of Florida for three years.”10

That same spring Tom Swope did a piece on Lefty for the Cincinnati Post with the headline “Knuckleball Ace Acts like Hillbilly but Reds Find Him Dumb like a Fox.” Swope wrote, “Because he was christened Witt and is left-handed, he’s had to stand for being called Halfwitt much of his life. … He has, in fact, encouraged the idea that he’s a hillbilly. But Witt O. Guise, 32-year-old southpaw knuckleball rookie of the world champion Reds, is nobody’s fool. He’s well educated and also has a bald head filled with native smartness which includes plenty of baseball sense and a love of the outdoors.”11

Guise did not survive the spring-training cuts made by the 1941 Reds, being sent to their Birmingham Barons club in the Class A1 Southern Association. It’s hard to pinpoint the reason: Only Milt Shoffner, traded to the Giants during the offseason, and Lefty failed to make the 1941 Opening Day roster after finishing 1940 on the Reds’ staff. The only new pitchers were Monte Pearson, a righty starter who didn’t appear in a game until mid-May, and Bob Logan, a left-handed reliever a year and a half younger than Guise. It appears that Logan was meant to fill Guise’s spot, but Logan pitched in only a couple of April games before heading back to Indianapolis, where he pitched every season from 1932 through 1946. The real differences on the 1941 Cincinnati staff that made Guise expendable were southpaw Vander Meer’s return to health and the emergence of Elmer Riddle as a one-year superstar.

One of Lefty’s Birmingham teammates was Hank Sauer, who would go on to become the National League MVP as an outfielder with the Chicago Cubs in 1952. Less than two months into the season, Guise and Sauer, at that time a first baseman, were involved in a frightening incident during a game in New Orleans. With Guise pitching and a man on first, a groundball was hit to the right side of the infield, and as manager Oscar Roettger described it, Lefty “went over to cover first and Sauer was right on top of him when, trying for a play at second, he threw that ball with all of his might. The ball bounced 40 or 50 feet [off Lefty’s skull] into right field, so far that the runner on first had plenty of time to reach third base. Guise refused to leave the game. He insisted that he was alright and that he continue pitching. He went to the mound and then his legs collapsed under him. Why, the blow was hard enough to knock out the average man.”12 A blood clot developed behind Guise’s ear and forced him to take substantial time off before rejoining the team. Nevertheless, he finished the year at 5-5 with a team-best 3.17 ERA.

Guise encountered a different type of 1-A classification after the season, when he was drafted into the US Army and trained at Camp Robinson in Little Rock. His family has the letter that Captain Verne E. Pate, his commanding officer at the Headquarters Reception Center there, wrote shortly after his Army induction; it went to Paul Florence, president of the Birmingham Barons. In it Pate describes Private Guise as “modest and unassuming … with a dry sense of Arkansas humor plus a lot of baseball ability. … If you have any more boys like Pvt. Guise send them on.”13 Within a month of his induction, he was pitching for (and helping coach) the Reception Center squad, which went on to three stellar seasons playing against semipro and military teams in and around Little Rock. By 1945 Guise was a staff sergeant and had moved on to Camp Chaffee in Fort Smith, Arkansas, where he was one of three pitchers on the War Department Personnel Center team. That team finished with a remarkable record of 37 wins against only 7 losses and won a pair of games in the National Baseball Congress World Series in Wichita. Guise capped the 1945 season, and his military baseball career, by throwing a no-hitter in the team’s final game and going 3-for-3 at the plate.14

The war years saw another major change in Guise’s lifestyle. In Tom Swope’s 1941 spring-training article, he had described Lefty as “one of the few bachelors now in Red togs,” and attributed that to his “three great loves – baseball, fishing and hunting,” quoting him as saying, “Might settle down and get married one of these days, but I lost so much time from organized baseball because of an injured back that I decided to stay single for a while.”15 Bachelorhood’s end was not far off, however: During the offseason back in Magazine just before his induction into the Army, he became acquainted with Mayrine Loyd Hopkins, a local girl a few years younger than he was, and her two daughters from a previous marriage. About the time Guise was inducted and sent to be stationed in Little Rock, Mayrine began working as a nurse in a hospital about an hour south in Pine Bluff. Their courtship blossomed, and they were married on March 6, 1943. After the war they set up housekeeping back in Magazine, where the four of them lived during the offseason, as Lefty prepared to rejoin the Birmingham Barons in the spring of 1946.

The uncertainties of wartime had made minor-league affiliations more tenuous, and Birmingham had lost the Reds connection in 1944, eventually picking up a working agreement with the Pittsburgh Pirates for 1946. With all the other competition from returning servicemen, the Birmingham front office soon decided there was no room for a 37-year-old soft-tosser, and Lefty was released on April 30. He caught on with the new Vicksburg (Mississippi) team of the Class C Southeastern League, and soon established himself as the team’s left-handed ace, going 14-8 with a team-best 2.66 ERA. The next two years were nearly as good, as he went 15-13 and 15-11 while posting ERAs of 4.03 and 3.87. In 1949, at age 40 and being 14 years older than anyone else on the pitching staff, he recorded his fourth straight season of double-digit victories, winning 11 games and losing 12 with an ERA of 3.31. The next season he slipped to 9-12, but his 4.03 ERA still led the team’s starters. The team folded after the 1950 season, and 1951 found Guise with the Douglas Trojans of the Class D Georgia State League.

Guise’s final year in the minors was a fitting climax to a remarkable baseball odyssey that had lasted more than two decades. He did everything but write the newspaper accounts for the Douglas team – he was the manager, the team bus driver, and the star pitcher. Along the way he acquired the additional nickname of “Pappy,” and managed the winning team in the league all-star game. The Douglas team finished fourth out of six teams in the regular season with 62 wins and 68 losses; the class of the league was the Jesup Bees, who were 86-43. In the league’s Shaughnessy Playoff structure, Douglas faced the Bees for a berth in the finals – and beat them four straight, allowing only five runs in the process, with Guise throwing a one-hitter in game two.16 Then Douglas faced the Eastman Dodgers for the championship, and fought back from a 3-1 deficit to win the seven-game series, with Lefty pitching and winning game six.17

However, perhaps the most historically noteworthy incident in that season happened off the field: Around the end of June, a young writer from the Atlanta Constitution doing a series on “Class D league towns and personalities” came to Guise’s house to interview him. The writer was Furman Bisher, barely a year into his career with the Atlanta newspapers – a career that would last for 59 years and earn him accolades as one of America’s premier journalists, not just among sportswriters but among all types of reporters.

The interview itself is a priceless recounting of Lefty being his country-charming self. He spun tales of rookies he’d seen in the dusty ballparks around the league; speaking highly of young Don Rudolph, he said, “They’re working him about every other day. If he’s got an arm left after this season, then I know he’s good.” (Rudolph went on to win 28 games, the most in Organized Baseball that year, and eventually pitched six seasons in the majors.) Guise went on to tell of another pitcher he’d seen at Jesup – a 55-year-old rookie who had “been in semi-pro around the Ogeechee League and Flint River League for years, but never played any pro ball before. They needed some pitching and they signed him. He’s been getting some men out. I [have] been in baseball 21 years and that’s the first 55-year-old rookie I ever saw.”

Bisher dutifully recorded the story without comment. Lefty went on to describe his early years in Florida, and his participation in the cleanup after the Lake Okeechobee hurricane in ’28 (he remembered it as ’26) which killed nearly 2,000 people (“They buried them as quick as a bulldozer could dig a hole. Worst thing I ever saw.”). He moved on to his days pitching in North Carolina (“the dangedest outlaw league you ever saw. … Virgil Trucks was on my team. We’d sent down to Alabama for him. He won one game for us under the name of Richard Aiken, and here come his daddy. He yanked him by the ear and took him back to Andalusia.”) He allowed that the eventual call to Cincinnati in 1940 was a thrill (“Nobody was more surprised than I was. I still wouldn’t believe I was the right man until I walked into the office and heard them pronounce my name”), but that he was frustrated he didn’t pitch more. (“I complained to [manager] Bill McKechnie one day about not pitching enough. He pulled the roster on me. He asked me to take a pencil and scratch off the guy I could replace, so I passed.”) He also told Bisher he was with the Reds “from August through the World Series and the 1941 season, but I got tired of sitting on the bench. … I was ready to go when they sent me to Birmingham.” Of course, the assignment to Birmingham actually took place before the 1941 season started.

The interview continued with his musings on continuing to pitch well into his 40s: As a manager, “I hadn’t planned on working until I could get a look at all my kids. Now it looks like I’m going to have to take my regular turn. Thing with these kids, they don’t know how to do anything but throw hard. They don’t want to learn about pitching. … Don’t guess I can complain too much, it took me a few years, too. … If you’re ever around Magazine, Arkansas, look me up. I’ll be back there every winter raising steaks and fishing. You’re welcome any time, boy.”18

Like many other ballplayers of his time, especially those who didn’t make the majors quickly, Witt Guise’s age was a moving target. For most of his career, it appears his baseball age was a year younger than what his birth certificate asserted. Furman Bisher described him as 41 in the July 1951 interview, and almost every other writer dating back to his Tarheel League days shaved a year off the calendar reality. This was a fact of life for many older ballplayers in that era: Virgil Trucks was two years older than all his teammates thought he was throughout his playing career. Of course, the hillbilly personality Guise so often projected for his public image went along with a certain uncertainty about his true age.

Life after Organized Baseball found Lefty back in Arkansas, working as a mechanic for the Arkansas National Guard. He was diagnosed with stomach cancer in 1962, but the disease went into remission until 1968, when it returned and progressed rapidly, eventually causing his death on August 13. His widow, Mayrine, survived until 1977; one of their daughters died in 1997, and their surviving daughter, Bobbye Pratt, lived in Arlington, Virginia, as of 2015.

In the first couple of decades of the 20th century, some pretty fair major-league pitchers were born in the small towns of Arkansas, and most of them were colorful and memorable characters: Lon Warneke, Gene Bearden, Johnny Sain, Dizzy and Paul Dean, Marlin Stuart, Hank Wyse, Ellis Kinder, and Preacher Roe. If things had been just a bit different, perhaps Lefty Guise would have been as well-known as any of them.

Notes

1 Whitney Martin, “Rookie Back After 7 Years,” Milwaukee Journal, February 28, 1941.

2 Furman Bisher, “The Man From Magazine,” Atlanta Constitution, July 2, 1951.

3 R.G. (Hank) Utley and Scott Verner, The Independent Carolina Baseball League, 1936-1938 (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company, 1999), 52.

4 Abe Fennell, “This Is Something Like the Fable of the Ugly Lil’ Duck,” The State (Columbia, South Carolina), April 18, 1940.

5 “Guise Gets Credit for Win Before Crowd of Nearly 8,000,” The State, July 9, 1940.

6 “Witt Guise Gets Boost From Associated Press,” The State, July 20, 1940.

7 “S-Sgt. Witt Guise: Veteran Pitcher,” Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock), August 6, 1944.

8 Ira Smith, Baseball’s Famous Pitchers (New York: A.S. Barnes and Company, 1954), 215.

9 Pete Norton, “The Morning After,” Tampa Tribune, March 3, 1941.

10 Whitney Martin, “Rookie Back After 7 Years,” Milwaukee Journal, February 28, 1941.

11 Tom Swope, “Knuckleball Ace Acts Like Hillbilly But Reds Find Him Dumb Like a Fox,” Cincinnati Post, March 24, 1941.

12 Naylor Stone, “You Must Admire Fellows Like Our Mr. Witt Guise,” Birmingham Post, May 31, 1941.

13 Letter dated April 29, 1942, in Bobbye Pratt family collection. Bobbye Pratt has preserved the extensive scrapbook her mother compiled on Witt’s baseball career after 1939; this scrapbook, and extensive conversations in 2015, provided the framework for this biographical work.

14 “Guise Tosses a No-Hitter, Wins Closing Game of Local Season,” Southwest American (Fort Smith, Arkansas), October 2, 1945.

15 Tom Swope, “Knuckleball Ace.”

16 “Guise Hurls One-Hitter as Trojans Whip Bees, 5-0,” Macon Telegraph, September 5, 1951.

17 Charles E. Franck, “Franck-ly Speaking,” Vicksburg Evening Post, September 29, 1951.

18 Furman Bisher, “The Man From Magazine.”

Full Name

Witt Orison Guise

Born

September 18, 1908 at Driggs, AR (USA)

Died

August 13, 1968 at Little Rock, AR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.