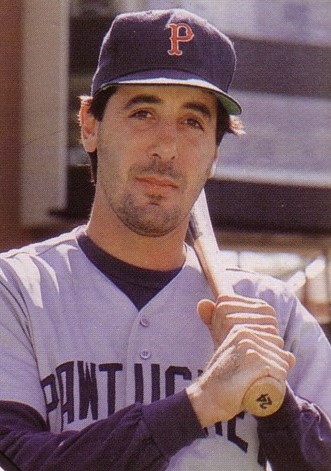

Rick Lancellotti

The Journeyman. That is the title of the book Richard Anthony “Rick” Lancellotti has selected to describe his baseball career when it is written. A more appropriate word could not be found in the English dictionary. After all, how many other baseball players have had a 17-year career and played in 15 leagues, in seven countries and more than 100 cities? Along the way, Rick was a prodigious slugger, leading four leagues in home runs: the Eastern League in 1979 with 41, the Pacific Coast League in 1986 with 31, the Japanese Central League in 1987 with 39, and the International League in 1991 with 21.

The Journeyman. That is the title of the book Richard Anthony “Rick” Lancellotti has selected to describe his baseball career when it is written. A more appropriate word could not be found in the English dictionary. After all, how many other baseball players have had a 17-year career and played in 15 leagues, in seven countries and more than 100 cities? Along the way, Rick was a prodigious slugger, leading four leagues in home runs: the Eastern League in 1979 with 41, the Pacific Coast League in 1986 with 31, the Japanese Central League in 1987 with 39, and the International League in 1991 with 21.

The word “journeyman” also describes Rick’s youth. He was born in Providence, Rhode Island, on July 5, 1956, and lived in nearby Warwick until he was five years old. His father was in the insurance business and the family moved with each promotion he received. As a result, Lancellotti lived in Montpelier, Vermont, until he was eight, then in Concord, New Hampshire, between the ages of 9 and 16. His life in Concord was very enjoyable and he participated in a variety of sports. In addition to baseball, he skied and played football and basketball. Rick and his family moved to Cherry Hill, New Jersey, when he was a junior in high school. The move was tough for the teenager as he was leaving behind a comfortable smaller-town environment for one where he didn’t know anyone and the high school was much larger: 3,500 students as opposed to 800 in Concord. Some 150 students tried out for the baseball team and, though he was an outfielder, Rick ended up making the team as a pitcher. He tried out for a mound position because there were only two or three left-handed pitching candidates as contrasted to 50 or so outfield candidates. Once he made the team, his hitting prowess became evident.

Rick’s school grades suffered as a result of his move to Cherry Hill and his future after high school was uncertain. He didn’t have any college scholarship offers during his senior year and considered joining the Marines. About a week before graduation the coach from Glassboro State College (in the 1990s it changed its name to Rowan University) talked with Rick and he ended up going there. Rowan had a strong program, going to the Division III World Series three years in a row and winning championships in 1978 and 1979. Rick’s high-school coach wanted him to go to Southern Illinois, a Division I baseball powerhouse. He was cool on that option because he felt that he wouldn’t get sufficient playing time and his options in professional baseball would thus be limited. At Rowan he made the team as a freshman, one of only two freshmen to make the team, and he was the cleanup hitter as a freshman. During the summer of 1976, he played in the Atlantic Collegiate Baseball League and put up offensive marks that still stood 35 years later as among the best in the league’s history. He hit 16 home runs, drove in 51 runs, and had an.836 slugging percentage as a member of the Berkshire Red Sox. At Rowan, Rick made the Division III Championship All-Star Team in 1977 – as a pitcher no less.

In 1977, at the end of his junior year in college, Lancellotti was drafted by the Pittsburgh Pirates in the 11th round of the major-league draft. He told an interviewer that he was surprised by the selection because the Pirates had shown little or no interest in him beforehand. (The Phillies had shown a lot of interest, he said, but did not draft him.) Lancellotti was eager to sign but his father rejected the Pirates’ initial offer of a $3,000 bonus. A week later, Murray Cook, the Pirates’ scouting director and farm director, called him with a “take-it-or-leave-it” offer of $4,000. Murray had seen Lancellotti at a tryout camp in Pennsylvania and felt that he was a prospect worth drafting. After spending a nervous and sleepless week following rejection of the $3,000 offer, Lancellotti took the $4,000 without hesitation. (His father mentioned that the sleeplessness had paid off with an extra $1,000.)

Lancellotti was assigned to the Pirates’ Charleston, South Carolina, affiliate in the Class A Western Carolinas League. His debut had a touch of humor. He joined the team on the road in Shelby, South Carolina. He arrived at the ballpark two hours early and chatted with some ballplayers in the dressing room. After trading stories with the players for 20 or 25 minutes, he decided that he should meet the manager. It was then that he discovered he was in the dressing room of the Shelby Reds and not the Charleston Patriots. The opposition had a good laugh at his expense. The Shelby catcher related the story to the home plate umpire during Lancellotti’s first at-bat, and Lancellotti smirked. The Reds pitcher thought Lancellotti wasn’t taking him seriously and drilled him with a fastball in the ribs. He apologized when he found out the true reason.

Lancellotti finished out the 1977 season with the Charleston Patriots, about two months, hitting .264 with nine home runs. In 1978, he was promoted to the Salem Pirates in the high-A Carolina League and batted .241 with 15 home runs. He was second among the league’s outfielders with 15 assists, an achievement that was offset by his league-leading 15 errors.[1] Lancellotti said he and his teammates in the low minors formed tight bonds because none had any money or material possessions to speak of.

After Salem, Lancellotti played winter ball in Mexicali, Mexico. His salary was about $1,000 a month, double what he had received in minor-league ball. In all, he played four seasons of winter ball, in Colombia and Venezuela as well as Mexico.[2] In Mexico he encountered 20-hour bus rides with boom boxes blasting in the pre-IPOD/MP3 player days; being stopped and inspected by the Federales, the Mexican federal police, in the middle of nowhere looking for handouts and bribes; being confined to his hotel room because of the danger outside due to drug wars; being confined to his apartment for an extra week after his team lost its last eight games in a row and blew a seven-game lead. Lancellotti said a ballplayer he knew was kidnapped because he was traded to a new team and was going to replace the team’s star. The player escaped but the police did nothing about it because they didn’t believe his story, Lancellotti said.

Promoted to Buffalo of the Double-A Eastern League for 1979, Lancellotti got off to a poor start. He started the season hitting seventh or eighth in the lineup and did miserably. Then he spoke with manager Steve Demeter in late April or early May about hitting cleanup. Lancellotti said he needed the pressure of batting fourth to do well. Demeter gave him a chance and Lancellotti responded with a breakout season, so much so that he was named the league’s Most Valuable Player. He batted .287 and led the Eastern League in slugging (.585), total bases (296), runs batted in (107, tied with Joe Lefebvre of West Haven), and home runs (41, seven more than runner-up and teammate Tony Pena). He tied the league’s 49-year-old home run record, though a short right-field fence at Buffalo’s War Memorial Stadium was a factor. He made 16 errors, second among the league’s outfielders, and had 13 assists. He was named to the league’s All-Star team.

Lancellotti’s teammates thought his season merited a September call-up to the Pirates, but, among other reasons, the Pirates thought his statistics were inflated by the dimensions of the ballpark. [3]

Lancellotti himself was just hoping to be called up to Triple-A the next season and he was, with an assignment to Portland of the Pacific Coast League. There his career took a step backward as he hit only .221 in 61 games as a platoon player for the Portland Beavers. In July he was sent back to Buffalo, where he hit .262 in 30 games. On August 5, Pittsburgh traded him to San Diego. The Padres assigned Lancellotti to Amarillo of the Double-A Texas League.

The trade had a significant impact on Lancellotti’s psyche. He thought the change was good because he went to a new organization that valued him. On the other hand, he felt like a lost soul because he had no friends and had to start all over in a new organization. Lancellotti was buoyed by the fact that the San Diego farm director told him the Padres had planned to send him to Triple-A but there was a right fielder at that level that they were fearful of releasing. He said San Diego decided to wait until the offseason and release him by mail, avoiding a face-to-face confrontation. In spite of his feelings, Lancellotti hit .380 in 22 games for the Gold Sox.

Lancellotti spent the next two seasons with the Padres’ Triple-A team in Hawaii. He hit.253 in 1981, splitting his playing time between the outfield and first base. His defense improved as he made only three errors in 93 games in the outfield. In a way, he said, it was tough to play in Hawaii because of the long homestands and road trips, 16 days each. He said he experienced “cabin fever” because of the homestands. The Islanders played in Aloha Stadium (home of the NFL’s Pro Bowl). Strong winds blowing from the right-field corner to the left-field corner created a nightmare for left-handed batters. That made the 19 home runs he hit in 1981 and 20 in 1982 a real accomplishment. The road trips required redeye flights of six hours to the West Coast followed by a connecting flight to the game city, and the team often arrived at the ballpark just before game time after flying all night. But Lancellotti thought that the PCL was the best league to play in outside of the majors because of all of the cities in it.

In 1982, Lancellotti hit .272 in 136 games for the Islanders and was called up to the Padres in August. Hawaii manager Doug Rader decided to have some fun at Lancellotti’s expense. Lancellotti had 20 home runs and 95 RBIs. Rader called a team meeting and laid out statistical goals for the players as the season wound down. He told Lancellotti that he had 95 RBIs but that he doubted he would get to 100. Lancellotti was puzzled until Rader told him he was going up to San Diego.

Lancellotti arose at 4:00 A.M. to catch a 6:00 A.M. flight so he could arrive at the ballpark in time for the game. When he got there, Padres manager Dick Williams told him he was playing first base that night against the St. Louis Cardinals. Facing the Cardinals’ Joaquin Andujar, he struck out in his first at-bat. Then he flied out twice and grounded out against Andujar and reliever Bruce Sutter. The next night, facing Ken Forsch, he grounded out in his first at-bat, but the next time he doubled with the bases loaded, driving in all three runners. He played in 15 more games before the end of the season, mostly as a pinch-hitter. In all, he had seven hits for a .174 batting average. Lancellotti attributed his performance to being new to the league and getting acclimated to the environment.

Lancellotti’s joy at being in the majors soon turned to despair when, playing left field in a September 8 game in Cincinnati, he injured his shoulder running into a fence on a ball hit over his head by Ron Oester. San Diego was leading 4-1 in the sixth with two runners on and two out. Despite running into the fence, Lancellotti made a run-saving catch. That injury, for all intents and purposes, ended his season, in part because of an ensuing confrontation provoked by manager Williams. Dick Williams managed through intimidation. He wanted Lancellotti to report to him at 2 p.m. the next day for treatment. Rick was 15 minutes late because of highway construction. As he told it, a heated conversation provoked by Williams ended with Williams telling Lancellotti that he would never play for him again. Still, in the remainder of the season Lancellotti pinch-hit seven times (one single) and played first base in one game, going 0-for-2.[4]

After the season the Padres sold Lancellotti to the Montreal Expos, who sent him to their Wichita farm team in the American Association. Lancellotti said he never felt he was needed there, as evidenced by his lack of playing time. He did poorly and was released after playing in 31 games. Doug Rader was managing the Texas Rangers at the time and the Rangers signed Lancellotti. He ended up with Oklahoma City, where he did even worse than in Wichita, and was released after playing 33 games.

Despite Dick Williams’s tirade, the Padres re-signed Lancellotti and sent him to Las Vegas of the PCL, where he finished with a flourish, hitting .302 with 32 RBIs in 30 games. Lancellotti played all of 1984 in Las Vegas and had 131 RBIs, the most in the minor leagues that year. He hit .287 and was selected to the Pacific Coast League All-Star team.

Still, the Padres cut him loose, trading him to the New York Mets before the start of the 1985 season. Lancellotti played for the Tidewater Tides of the International League and hit only .180 in 91 games. On July 31 the Mets sold to the San Francisco Giants and he finished out 1985 in Phoenix, batting.210 in his 33 games there. He began 1986 in Phoenix, improving to .275 with 106 RBIs and a league-leading 31 home runs. The Giants called him up in June and again in September. Overall with the Giants he went 4-for-18, but on September 21 and 23, in consecutive at-bats as a pinch-hitter, he hit home runs, a two-run shot off Atlanta’s Jeff Dedmon and a three-run blast off Cincinnati’s Ron Robinson. Lancellotti is one of only 50 major leaguers (as of 2010) to hit back-to-back pitch-hit home runs. (His attempt to join the three players who did it three times in succession failed when he was struck out by Nolan Ryan.)

During 1986 the Hiroshima Carp of the Japanese Central League had been scouting Lancellotti and wanted to sign him. Lancellotti was torn because he wanted to stay with the Giants but only if they could guarantee him a legitimate shot at a roster spot. The Giants would not make such a guarantee, and Lancellotti reluctantly signed a two-year contract with the Carp. In his first season, 1987, he led the league with 39 home runs while batting .281 and striking out 114 times. During the season he set a record by hitting home runs in six straight games. But he told an interviewer was miserable there and felt that he had sold his soul for money. His performance slipped badly during his second season, to .189 with 19 homers in 79 games. Lancellotti became embroiled in a controversy when he accused the manager of the Carp of trying to lose games because he was not going to return the next year. The team vowed to send Lancellotti to the minor leagues, then threatened to withhold his pay. Eventually Lancellotti and the Carp reached a settlement and he returned to the US.

After his return Lancellotti caught on with the New York Yankees for 1989 spring training and hit about .400, but was released anyway. Lancellotti was now out of baseball and miserable. Then the Pawtucket Red Sox, the Boston Red Sox’ top farm team, came to Buffalo (where Rick and his family were living) to play the Bisons. The Pawtucket manager, Ed Nottle, was a friend. They spoke, and eventually Lancellotti signed with Pawtucket. He started slowly, hitting about.120 with about two RBIs in his first month, but eventually he came around and wound up hitting .254 with 60 RBIs and 17 home runs, second best in the International League.

Lancellotti spent the next two years with Pawtucket. He hit .254 in 1989 with 17 home runs, then slipped badly in 1990, to .223, though he hit 20 homers. Still, he was called up to the Red Sox for a short stint in August. He was hitless in nine plate appearances, but drove in a run with a sacrifice fly.

After the season Lancellotti squeezed in a stint with the Sun City Rays of the Senior Professional Baseball League, in Florida. He lied about his age, claiming he was older than he actually was (usually when players lie about their age it’s to make them appear younger). He hit .264 with five home runs in 23 games. Lancellotti was back with Pawtucket in 1991. He batted only .209 but his 21 home runs were tops in the league;

Lancellotti spent 1992, his 16th and final year as a player, in the Italian Baseball League, playing with the city of Parma Angels. The schedule was to his liking: three days of practice, two game days, and two days off. He hit.315 in 36 games, with seven home runs and 37 RBIs. After that, at the age of 36, he retired as a player.

He and his family (his wife, Debra, the daughter of Jim Ludtka, a minor leaguer in the 1950s, and two children, Joseph and Kaitlin) settled in Clarence, New York, a suburb of Buffalo. He was a prominent figure in baseball in the Buffalo area, where he operated sporting goods stores. Rick and Debra have two children, a son Joseph and a daughter Kaitlin. In 1993 he began the Buffalo School of Baseball in Cheektowaga, New York. [5] For a period he was an assistant coach of the baseball team at Erie Community College. In an interview he said he tried to instill in people that they should follow their passion and not let anyone tell them that they can’t do it. He said he loved everything about the game and got to the stadium hours before the game and left hours after it ended, that he gave the game his best shot and left it without any regrets. He said he was thankful that he got to play in the major leagues, for however short a time.

March 10, 2011

Sources

SABR Oral history interview with Lancellotti, July 25, 2001

SABR Oral history interview with George Murray Cook, December 10, 2009

Thomsen, Ian, “Life in the Minors: No Fame or Fortune, Only Diamonds in 7 Countries,” New York Times, April 7, 1992

Full Name

Richard Anthony Lancellotti

Born

July 5, 1956 at Providence, RI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.