Hi Bithorn

While much mystery surrounds the life and career of the first Puerto Rican to play major-league baseball, there’s no question that Hiram “Hi” Bithorn’s entrance into the big leagues raised his island’s self-esteem as well as opened the door for future Puerto Rican baseball players to realize their dreams, too. With the passage of time, memories of the “Tropical Hurricane” – as some called him – reside primarily with the old-timer players and fans who saw him pitch in the 1930s and 1940s. Even though the largest stadium on the island bears his name, today many residents of his homeland know little about Hiram Bithorn.1

While much mystery surrounds the life and career of the first Puerto Rican to play major-league baseball, there’s no question that Hiram “Hi” Bithorn’s entrance into the big leagues raised his island’s self-esteem as well as opened the door for future Puerto Rican baseball players to realize their dreams, too. With the passage of time, memories of the “Tropical Hurricane” – as some called him – reside primarily with the old-timer players and fans who saw him pitch in the 1930s and 1940s. Even though the largest stadium on the island bears his name, today many residents of his homeland know little about Hiram Bithorn.1

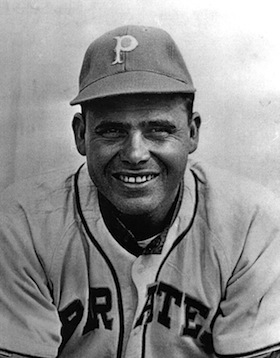

He was a talented athlete. Standing 6 foot 1 inch and weighing about 200 pounds, Bithorn commanded attention when he took the mound, began his distinctive windup, raised his long left leg high in the air and followed through with a powerful right-hand pitch over home plate, striking out one batter after another. He had remarkable control and delivery of a straight-line 90- to 95-mile-per-hour fastball that at least one time resulted in a hand injury that required a change of catchers.2 But, it would take more than technical skill and brawn for this Latino baseball player to make it to the big leagues in the 1940s.

Historically, Latinos had been playing in the major leagues since the early 1900s,3 and while earlier Puerto Rican players may have had the right stuff for the big leagues, until Bithorn came along, the color of their skin was deemed too dark for the all-white clubs of that time. Born March 18, 1916, in an area of San Juan called Santurce, Bithorn came from a family of Danish-German-Scottish and Spanish descent.4 He had light olive skin, spoke English, and his name did not sound Latino. Besides, he had a mean pitch.

Hiram’s father, Waldemar G. Bithorn, was a municipal employee while his mother, Maria Sosa, was a public school teacher. Hiram, the fourth of five Bithorn children, had three brothers, Waldemar, Fernando, and Rafael, and a younger sister, Maria Angelica.

According to Jorge Colon Delgado, baseball historian of Puerto Rico, the Bithorns were an exceptional family that traveled frequently to the United States.5 His mother taught her children English, and at one time produced a radio program called “Abuelita Borinqueña” (“Puerto Rican Grandmother”)6. Hiram attended Central High School in Santurce. His brothers Waldemar and Fernando, 11 and 10 years his senior, encouraged and assisted in training him to become an athlete. Even though during his childhood Hiram lost the big toe on his right foot in some kind of railway accident, the absent digit did not stop him from excelling in sports.7

In 1935, he played in the Third Central American and Caribbean Games in El Salvador, helping his island teammates bring home a silver medal in volleyball and a bronze in basketball. By this time, however, he had already begun making a name for himself in baseball. One game in particular occurred in the town of Guayama in 1932. Bithorn was on a team of nativos playing against Richmond, a team of white players, including first baseman, batting phenomenon, and future Hall of Famer Johnny Mize. That day 16-year-old Bithorn pitched a 10-1 game for the nativos.8

In Bithorn’s day, attending baseball games in Puerto Rico and rooting for the home team was as much a social event as a sporting event. This is where people gathered to pass the time, catch up with the latest news and gossip as well as support the young athletes of their island. But it was a time when Puerto Ricans did not have a good self-image, believing that anything of value must come from outside. Bithorn’s success would help change that perception.9

Most games in San Juan were played in Sixto Escobar in El Escambron, where local fans filled the benches and even climbed into the trees outside the ballpark to secure a good vantage point to watch Bithorn at work.10 It was just a matter of time before he’d get a chance to play in the United States, and eventually in the major leagues. The opportunity came in 1936 when two individuals saw something special in him.

That year the Newark Eagles (created with the 1936 union of Brooklyn Eagles and Newark Dodgers) of the Negro National League had gone to San Juan ahead of an exhibition series against the Cincinnati Reds. While warming up with some practice games against the local Puerto Rican teams, the Eagles were impressed with Bithorn’s performance on the mound. When one of their star pitchers, future Hall of Famer Leon Day, had an attack of appendicitis,11 the Eagles invited the Puerto Rican to join their short-handed pitching squad against the Reds, a team led by future Hall of Famer Kiki Cuyler.12

That is how it happened that on March 1, 1936, 20-year-old Bithorn pitched his first game against a major-league club. For seven innings, he allowed Cincinnati only one run, but when the Reds scored three runs in the eighth inning, the Eagles brought in a relief pitcher to save the game.13 The Eagles took the game, and Bithorn would get the break he needed to play in the United States.

Frank Duncan, catcher for the Eagles in that series, is credited with helping the Puerto Rican polish his pitching technique, while outfielder Ted Norbert recommended him for a contract with the Class B Norfolk Tars of the Piedmont League.14 Bithorn would spend six seasons in the minor leagues, moving up midseason 1937 to the New York Yankees’ Class A Binghamton Triplets. Midseason 1938 he continued to improve, advancing to the Newark Class AA team, also affiliated with the Yankees. In his first two seasons in the minor leagues, he pitched 16-9 and 17-9 respectively.

Author Nick C.Wilson shares an unusual story from Bithorn’s minor-league days with Norfolk. After winning the first game of a doubleheader on a Thursday evening, he took a seat in the stands to watch the second game, still wearing his uniform. As it turned out, the game dragged on inning after inning until the entire Norfolk pitching squad was depleted. Manager Johnny Neun looked into the grandstand and called Bithorn to pitch the rest of the game. Finally, at two a.m. on Friday, Norfolk drove in two runs in the 15th inning, and as Wilson reports, “Bithorn had won back-to-back games on two different days without removing his uniform.”15

After each season in the States he returned to Puerto Rico to play in the Winter League, wearing the San Juan Senators uniform. Initially, because of his minor-league record in the United States, the Puerto Rican Professional Winter League classified him as blanquito (white), and then briefly changed it to refuerzo (outsider) before finally allowing him to play as a nativo.16 When San Juan manager Juan Torruella resigned only two weeks into the 1938 winter season, the Senadores chose 22-year-old Bithorn as manager, making him the youngest manager in the history of the Puerto Rican Professional Winter League.17

Hiram moved to the Pacific Coast League in 1939 where he acquired the nickname “Tropical Hurricane” or just “Hurricane” Bithorn. He played three seasons in the Class AA clubs Oakland Oaks and Hollywood Stars, achieving win-loss percentages of .481 (1939), .370 (1940), and .531 (1941). He closed the 1941 season with a 17-15 record. Two of those games were shutouts.

The Hollywood Stars that Bithorn played with was the second club by that name to make its home in the movie industry community, the first having moved to San Diego in 1936 to become the future San Diego Padres. Owners of the second Hollywood Stars, formerly the San Francisco Missions, determined to make the team a popular civic venture. To do this they formed the Hollywood Baseball Association and sold small shares of stock to local civic leaders as well as movie stars and moguls, promoting the club as “the Hollywood Stars baseball team, owned by the Hollywood stars.”18

Baseball players and movie stars appeared together in print advertisements as well as social and promotional events. Fraternizing among baseball players and movie stars was all part of the Hollywood environment in which the Puerto Rican found himself. According to family members, Hiram did well socially in Hollywood, and in particular, befriended actress Ida Lupino. Although there is no evidence to support the story that the two were romantically involved, it is at least interesting to note that the Bithorn name appears in her 1943 movie, The Hard Way. In one of two shots of a newspaper page, the name of the character Laura Britton reads Laura Bithorn, doubtless a nod to Lupino’s baseball-player friend.19 By the time the movie came out, the Hurricane was already playing in the major leagues.

At the end of the 1941 season, the Chicago Cubs drafted Bithorn from the Hollywood Stars, along with Cuban-born Salvador “Chico” Hernández, from the Texas League’s Tulsa Oilers, thus forming the third Spanish-speaking pitcher-catcher battery in major-league history.20 Not only did Bithorn and Hernández speak the same language, photographs reveal a striking similarity of physical features. Former Cubs shortstop Lennie Merullo described the two as very popular “big handsome guys.”21 They were born within three months of each other (Hernández on January 3, 1916, in Cuba, and Bithorn on March 18, 1916, in Puerto Rico). The pitcher stood only one inch taller and weighed only five pounds more than the catcher. Bithorn made his major-league debut with the Cubs on April 15, 1942, at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. Hernández made his the following day, April 16, 1942, also in St. Louis. Bithorn pitched two innings and allowed no hits in his debut game, which the Cubs lost, 4-2.

When playing teams with no Spanish-speaking players, Bithorn and Hernández openly conversed in Spanish on the field, calling out signals in what The Sporting News once called “Castilian Signal Code.” Of course, the scheme worked only when no other Spanish-speaking players or coaches were in the game. New York Giants manager Mel Ott may not have had a player to translate what the pitcher and catcher said to each other, but he had a Spanish-speaking coach in the legendary Cuban-born Adolfo “Dolf” Luque who understood every word.22

Bithorn pitched 171 1/3 innings in 38 games in 1942 with 9 wins and 14 losses, achieving a 3.68 ERA. The next year he pitched his career high of 249 2/3 innings, allowing only 227 hits in 39 games, 19 of which were complete games. He ended the season with 18 wins and 12 losses, and a 2.60 ERA. With seven shutouts to his credit, he led the 1943 National League, making him the second Latino to do so, the first being none other than Adolfo Luque in 1921 (3), 1923 (6), and 1925 (4). Today Bithorn continues to hold the record for highest number of shutout games by a major-league pitcher from Puerto Rico.23

Merullo described Bithorn as a hard thrower with a great curveball. “He had a natural sinker that he would throw from a low three-quarter position. When he pitched, we knew as infielders we were going to get a lot of work. He was always good, but you knew you were going to be busy.”24

Noteworthy are Bithorn’s 1943 wins against the reigning world champion St. Louis Cardinals. Even though the Cardinals would go on to win the pennant, Bithorn allowed them only two runs in 32 innings.

Teammates and family members remember Bithorn as good-natured guy and even somewhat of a prankster. Prior to the 1943 season, columnist Ed Burns commented, “He has been full of fun and wisecracks all spring. . . .”25 Cubs first baseman Phil Cavaretta said he was a hard worker, very quiet and dedicated to the game.26 El Imparcial writer Eduardo Valero recalled the time Bithorn came out of the dugout sporting an umbrella in protest of the umpire’s delay in stopping play due to rain.27 Merullo remembered him as a happy guy with a playful nature who could take a ribbing from his teammates.28

Despite his success as a major-league baseball player, Bithorn lived under a cloud of rumors and gossip regarding his racial ancestry. Simply the fact that he was Latino was enough to raise doubts in some minds and fuel suspicion that he might be a mulatto. Ever since the early 1900s, when the first Latinos were recruited to play organized baseball in the United States those responsible for policing baseball’s color line during the Jim Crow era had sought evidence of a player’s “whiteness” or Castilian blood line as a qualification for admission to a major-league team.29 The Cubs were satisfied that Bithorn was white, and in fact, published his biographical information stating he was of Danish and Spanish heritage.30 Nonetheless, Bithorn endured ethnic stereotyping and harassment from opposing players, fans, and managers, including New York Giants manager Leo Durocher, who discovered the limit of taunting the pitcher would take.

Durocher was hurling derogatory names at Bithorn as fast as the Puerto Rican could pitch hardballs on July 15, 1943. In the scenario Cavaretta remembered, the pitcher called for a time-out in the sixth inning, but instead of conferring with the catcher as he would be expected to do, Bithorn remained on the mound, staring straight at the batter. In a slightly different account reported in New York Age, the Cubs manager pulled Bithorn from the game, which sent the pitcher into a “frenzy of indignation.” In both versions of the story, Durocher’s diatribe of dirty words and racial slurs stopped abruptly when Bithorn shot the ball straight at him into the dugout, sending his target to his knees to avoid getting hit. It may have brought smiles to the faces of many observers, but Durocher and the commissioner of baseball, Ford Frick, failed to see the humor in it.” Bithorn received a $25 fine and reprimand.31 Major league commissioner Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis subsequently issued a public statement denying any “ban in organized baseball against the use of colored players, either by rule or by agreement or by subterfuge.”32

The question of Bithorn’s racial heritage would emerge again more than 30 years later when Hall of Fame journalist Fred Lieb revealed in his 1977 autobiography Baseball as I Have Known It, an incident that occurred in St. Louis in late 1946 or early 1947. He said a man whom he did not know invited him to a performance of an all-black dance troupe and made a point of introducing him to one of the dancers, who claimed her mother and Hi Bithorn’s mother were sisters. Afterward Lieb speculated that this meeting had been intentionally arranged in order to “tell me something,” but he concluded, “… I have since been assured by a Puerto Rican baseball authority that Bithorn was not black, despite my curious experience.” 33

Author David Maraniss confirms, “That Bithorn had white skin meant very little to fans in San Juan . . . . But it meant everything to the men who ran organized baseball in the States. It was the only reason they let him play.”34

Unlike other Latino players from Central America and the Caribbean, as a Puerto Rican, Bithorn was a U.S. citizen (as per the Jones Act of 1917), and thus eligible for the draft during World War II. While his request for a draft deferment was denied, the War Department reclassified him to 1-A. Inducted November 26, 1943, Bithorn served most of two years at the San Juan Naval Air Station in Puerto Rico where he was player-manager of the post’s baseball team.35

After his discharge on September 1, 1945, he reported to Chicago Cubs for the final weeks of the season, but did not play.36 Four months later, on January 3, 1946, Bithorn and Chicago native Virginia Arford were married in Mexico. The next month he injured his hand while playing in the Puerto Rican championship games, delaying his return to the Chicago Cubs for the 1946 season.37 He appeared on the mound in only 26 games in 1946 to garner six wins and five losses, primarily as a reliever.

Clearly, Bithorn was no longer the promising player who had pitched over 249 innings and seven shutouts in 1943. He’d gained about 25 pounds, and according to some, emerged from the military a changed man, grumpy, argumentative, and no longer the baseball star he had been before his military stint.38 While some have speculated as to what may have happened, the real cause of his changed personality and lost skills remains something of a mystery (though arguably a nagging arm problem must have been a contributing factor). Reports that he suffered a “nervous breakdown” while in the Navy are flatly denied by family members today.39 With his baseball career clearly on a downslide, the Cubs traded him to the Pittsburgh Pirates, but he never played for them. He was then selected off waivers by the White Sox, but plagued by that sore arm, he played only two games with the club.

His major-league career ended with his final game, the first of a doubleheader against the Philadelphia Athletics on May 4, 1947, at Comiskey Park. Bithorn pitched only one inning and allowed one hit, but got the 8-7 win over Philadelphia. Playing in 105 games during four seasons (1942, 1943, 1946, 1947), he accumulated a major-league win-loss record of 34-31 and a 3.16 ERA. He pitched 509 2/3 innings and allowed 517 hits while playing in the big leagues.

Sore arm or not, Bithorn was not ready to give up baseball. Returning briefly to the Class AAA Hollywood Stars, he managed to pitch four games, achieving one loss and no wins. He finally underwent arm surgery and missed all of the 1948 season. Back to the game in 1949, he pitched one game with the Class AA Oklahoma City team and 12 games with the Class AA Nashville club. He spent the final years of his baseball career playing and/or umpiring in Mexico and the Class C Pioneer League.40

Hiram and Virginia lived in Chicago when their only child, Hiram Jr., was born in May 1951. In the meantime, Bithorn’s mother, along with his sister and family had moved to Mexico City where Maria Angelica attended university. Plans were made for Hiram to sponsor the baptism of her one-year-old son, David Hiram Arechiga, during the year-end holidays. However, fearing the trip would be too difficult for her and the baby, Virginia and seven-month-old Hiram Jr. remained in Chicago while Bithorn headed out on the 1,685-mile journey alone.

Driving a 1947 Buick, he crossed the U.S.-Mexico border and traveled to the extreme southern part of the state of Tamaulipas to the town of El Mante along Federal Highway 85. Here he met his untimely death by a policeman’s bullet to his stomach. Exactly what happened that night remains a mystery, but apparently he stopped in El Mante to get a hotel room. While some reports say he had no money to pay for the room, another says he had $2,000 in U.S. currency with him.41 The policeman, Corporal Ambrosio Castillo Cano, claimed Bithorn attempted to sell his car to raise money for the hotel room, but had no license or registration papers for it. How he could have made it all the way from Chicago to Mexico without a license, registration, or money remains another puzzling piece of the Bithorn mystery.

According to Castillo’s version, he got into the car with Bithorn and ordered him to drive to the local police station. A fight ensued, and fearing for his life, the policeman shot the Puerto Rican. Bithorn was then transported by ambulance to a hospital 84 miles away in Victoria, and within an hour of arrival, the 35-year-old was pronounced dead of internal hemorrhage. While various sources give his date of death anywhere from December 27, 1951, to January 1, 1952, the most generally accepted date of December 29, 1951, is the one documented by an Associated Press reporter in Mexico. In Chicago, Virginia learned of her husband’s demise in a radio report, which she confirmed with a phone call to the Chicago Tribune.42

Bithorn’s family never bought the policeman’s story, believing he actually wanted to steal Bithorn’s car and personal belongings. Castillo’s story grew more convoluted as he attempted to place blame on the Puerto Rican. He even told Mexican officials that Bithorn admitted to being a member of the Communist Party and that he was on an important mission. Strangely, Puerto Rico’s newspapers said very little about his death, and no Puerto Rican journalists went to Mexico to investigate.43 However, Bithorn’s family insisted on an FBI investigation. Castillo was indicted on January 11, 1952, convicted, and sentenced to eight years for the murder.44

Outraged over the death and crude burial of the baseball player in Mexico, Puerto Rican officials and Bithorn’s family demanded that his remains be returned to the island for a proper Christian burial. At the request of Governor Luis Muñoz Marin and San Juan Mayor Felisa Rinc?n de Gautier, the U.S. ambassador to Mexico, William O’Dwyer, arranged with Mexican government officials for the transfer by air carrier. Bithorn’s decomposing body, covered with mud and still in the clothes in which he was killed, arrived in Puerto Rico on January 12, 1952. The next day, about 5,000 people filed past his casket on the field at Sixto Escobar Stadium prior to burial in Buxeda Cemetery, Isla Verde, only a short distance from his birthplace in Santurce, Puerto Rico.

As a symbol of respect for their former teammate and manager, the Senadores played the rest of the season wearing black patches on their sleeves. Ten years later, in 1962, the city of San Juan memorialized the island’s first major leaguer by naming its new 18,000-seat baseball park the Hiram Bithorn Stadium, a fitting tribute to the pioneer who opened the door for all the other Puerto Rican ballplayers who realized their dreams, and each in his own way contributed to the island’s legacy in major league baseball.

Bithorn’s wife, Virginia, who later remarried, died in 2011 in Arizona.45

A version of this biography is included in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández.

Notes

1 http://Autografo.tv/hiram-bithorn. 2012.

2 Ibid.

3 Adrian Burgos, Jr. Playing America’s Game (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 269-270.

4 Michael Bithorn interview by author, February 17, 2014.

5 http://Autografo.tv/hiram-bithorn.

6 Michael Bithorn interview by author, February 23, 2014.

7 http://Autografo.tv/hiram-bithorn.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Nick C. Wilson. Early Latino Ballplayers in the United States (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2005), 145.

13 Wilson, 146.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Burgos, 309.

17 http://Autografo.tv/hiram-bithorn.

18 Stephen M. Daniels, “The Hollywood Stars.” Baseball Research Journal #9, Society for American Baseball Research, 1980.

19 Interviews by author: Michael Bithorn, February 23, 2014, and David Hiram Arechiga, March 25, 2014.

20 The first was a pair of Cubans, pitcher Oscar Tuero and catcher Mike Gonzalez, St. Louis Cardinals, 1918, and the second was Cuban Adolfo “Dolf” Luque and Tampa-born Al Lopez, Brooklyn Robins, 1930.

21 Nick Diunte. Examiner.com. “Bithorn lead the way for Puerto Ricans in the majors.” Retrieved January 29, 2013.

22 Burgos, 171.

23 http://Autografo.tv/hiram-bithorn.

24 Diunte.

25 Wilson, 148.

26 Wilson, 147-148.

27 David Maraniss. Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2006), 28.

28 Diunte.

29 Burgos, 98.

30 Wilson, 147.

31 Wilson, 148.

32 Burgos, 172.

33 Fred Lieb. Baseball as I Have Known It (New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1977), 260.

34 Maraniss, 28.

35 Gary Bedingfield, www.baseballinwartime.com. March 29, 2008.

36 Wilson, 148.

37 Bedingfield, op. cit.

38 http://Autografo.tv/hiram-bithorn.

39 Maraniss, 30. Family interviews, 2014.

40 Bedingfield, op. cit.

41 Andrew Martin. “Hi Bithorn: Puerto Rico’s Baseball Pioneer.” The Baseball Historian. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

42 Jorge Colon Delgado. www.elnuevodia.com/blog-titulo-852202. December 29, 2010.

43 http://Autografo.tv/hiram-bithorn.

44 Wilson, 150.

45 Obituary in The Arizona Republic, May 20-22, 2011.

Full Name

Hiram Gabriel Bithorn Sosa

Born

March 18, 1916 at Santurce, (P.R.)

Died

December 29, 1951 at Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas (Mexico)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.