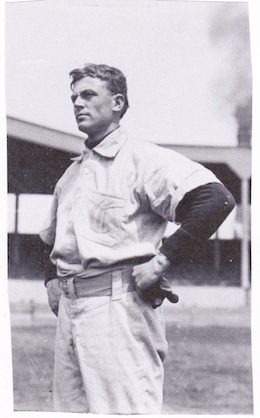

Bob Wicker

During the first decade of the Deadball Era, the Chicago Cubs boasted eight different pitchers who posted 20-win seasons for the club.1 Perhaps the least known of them is Bob Wicker, a strapping 26-year-old right-hander who went 20-9 in 1903. Unhappily for Wicker, he was traded to Cincinnati early in the 1906 campaign, thus missing out on the four National League pennants and two World Series crowns the Cubs would win in the coming five-season span. By the time that the Cubs completed their championship run in 1910, Wicker was out of Organized Baseball, pitching mostly for semipro teams. Still, Wicker soldiered on, pitching/managing in the Class B Northwestern League in 1915, and thereafter playing in the Chicago city league until he was nearly 40. The remainder of his life was spent quietly, living and working in the Chicago area until his death in early 1955.

During the first decade of the Deadball Era, the Chicago Cubs boasted eight different pitchers who posted 20-win seasons for the club.1 Perhaps the least known of them is Bob Wicker, a strapping 26-year-old right-hander who went 20-9 in 1903. Unhappily for Wicker, he was traded to Cincinnati early in the 1906 campaign, thus missing out on the four National League pennants and two World Series crowns the Cubs would win in the coming five-season span. By the time that the Cubs completed their championship run in 1910, Wicker was out of Organized Baseball, pitching mostly for semipro teams. Still, Wicker soldiered on, pitching/managing in the Class B Northwestern League in 1915, and thereafter playing in the Chicago city league until he was nearly 40. The remainder of his life was spent quietly, living and working in the Chicago area until his death in early 1955.

Robert Kitridge Wicker was born in Bono, Indiana, on May 25, 1877,2 one of at least eight children born to railroad messenger/clerk Walter Burton Wicker (1849-1940), and his wife, the former Lydia Ann Parrish (1853-1935).3 The Wicker family was of English descent and originally from the Winston-Salem, North Carolina area. In 1874, grandfather John Pharis Wicker relocated several generations of the Wicker clan to Lawrence County in rural south-central Indiana. Grandpa Wicker settled in Bono, a then-sparsely populated farming community, and served on the Bono Township governing board and as justice of the peace. His son Walter was also active in local affairs, serving as treasurer of the township’s dramatic society.4 For the most part, life was good for the Wickers in Lawrence County. But the family was far from immune to disease and the other hazards of late-19th century living. Four of Bob’s brothers and two Wicker cousins would die prematurely.5

Bob attended Bono elementary school through the eighth grade.6 In February 1890, Walter Wicker moved his family to Bedford, about 12 miles from Bono and the seat of Lawrence County.7 But Bob did not attend the local high school. Instead, he matriculated to Oak Ridge Male Institute, a military prep school back in Winston-Salem,8 but whether Wicker graduated is unknown to the writer. Thereafter, Bob returned to Bedford, and first received press notice playing baseball for the town’s amateur team in 1894.9 A tall teenager (who would eventually top out at 6-feet-2), the righty hitting/throwing Wicker was initially a shortstop-center fielder who pitched on occasion. The following summer, he was in almost constant action, playing for a newly organized Bedford Grays team, the nearby Loogootee Black Diamonds, and teams in Orleans and Mitchell, Indiana. Although still primarily a position player, “Bedford base ball cranks are unanimous in the opinion that Bob Wicker is the greatest Hoosier ball-tosser.”10 In the offseason, Wicker was an expert marksman, with his shooting/hunting exploits frequently noted in the Bedford Daily Mail.11

In May 1896 Wicker played center field for Bedford in a game against Indiana University, a squad that he would later coach. He also pitched and played shortstop for a team in Oolitic, Indiana, that season. But for the most part, Bob spent the summer playing for a semipro team in Paducah, Kentucky — until a case of malaria necessitated his return home to recuperate that September.12 The next year, he continued playing for local nines, before finally entering the professional ranks in 1898 by signing with Mattoon (Illinois) of the short-season Indiana-Illinois League. With future New York Giants right-hander Dummy Taylor the Mattoon pitching mainstay, Wicker mostly played center field. He did, however, toss a three-hitter in a 3-2 win over Springfield in early August,13 and another three-hitter weeks later against Evansville, winning 12-3.14 A season later, Wicker was Mattoon’s Opening Day hurler, posting a 12-10 victory over Bloomington.15 By late-season 1899, Wicker was deemed “probably the best pitcher in the league” by an unnamed Sporting Life correspondent.16

Wicker’s work did not go unnoticed and at season’s end, he was drafted by the Kansas City Blues of the upper echelon Western League.17 But that winter the Kansas City franchise went under, and Wicker spent the 1900 season with the Dayton Veterans of the mid-level Interstate League. Now 23 years old, Wicker blossomed, going 21-9 for a pennant-winning club, and batting .293 as an occasional fill-in at third base and the outfield. Toward the close of the season, he was drafted by the National League Pittsburgh Pirates and placed on the club’s reserve list for 1901. In the estimation of Cincinnati sportswriter Ren Mulford, Jr., however, the draft was merely a strategic maneuver, designed to keep Wicker from being taken from Dayton by a higher-tier minor-league club. As soon as the draft was completed, Mulford asserted, Pittsburgh would release Wicker, leaving Dayton free to reclaim him.18 In time, those predictions were vindicated, and Wicker began the 1901 season back in Dayton, now a member of the Western Association. But he would not be there for long.

Wicker delayed reporting until May, coaching the University of Indiana baseball team to a 3-3 record that spring. That log included a 4-3 victory pitched by Wicker himself over a team from Terre Haute that opposed him against future Cubs teammate and Hall of Famer Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown.19 Once Wicker arrived in Dayton, he stayed for about two months. In early July, Dayton club president-manager Bill Armour sold his contract to the St. Louis Cardinals for $1,500. The deal, however, would prove a disappointment to the Cards. Wicker reported with a sore arm, unable to pitch. His major-league debut on August 11, 1901, therefore took an odd form: as a pinch-runner when teammate Emmet Heidrick aggravated a charley horse running the bases in a game against Cincinnati. Wicker then finished the 3-2 extra-innings loss as the Cardinals’ center fielder, being robbed of a base hit in his initial major league at-bat by a “great running catch” by Reds outfielder Johnny Dobbs.20 Wicker later played twice more in the outfield for the manpower-strapped Cardinals, but could manage only one pitching appearance, an ineffectual relief outing in a 14-2 loss to Pittsburgh. Wicker finished the season out of uniform, dispatched by Cardinals manager Patsy Donovan to a West Baden, Indiana, spa for treatment of his arm miseries.21

Disgruntled by receiving damaged goods, St. Louis management subsequently reneged on payment of the $750 still due Dayton for acquisition of Wicker’s contract. Dayton boss Armour retaliated by placing an attachment on the Cardinals’ share of gate receipts when St. Louis played its first 1902 game in Ohio (Cincinnati). Litigation ensued, with an Ohio jury eventually being directed to return a $750 judgment, with interest, in Armour’s favor by the presiding judge.22 Meanwhile, Wicker, his arm restored, struggled on the mound, going 5-12 with a 3.19 ERA in 152⅓ innings pitched for a sixth-place (56-78) St. Louis team. The 1903 season started poorly as well, with Wicker dropping his first decision. Then fortune smiled on Bob Wicker. The Cardinals traded him to the Chicago Cubs in exchange for pitcher Bob Rhoads. The move to Chicago was a perfect fit for Wicker. Although a good-sized man, he did not have overpowering stuff. Like many Deadball Era hurlers, he pitched to contact, relying on good control and sound defense for success. And the Cubs, with the renowned infield of Joe Tinker, Johnny Evers, and Frank Chance, plus defensive stalwarts like catcher Johnny Kling and swift center fielder Jimmy Slagle, supported Wicker ably in the field.

New acquisition Wicker got off smartly, defeating Cincinnati 7-3 in his Cubs debut. He then settled into the Cubs rotation as the number-three starter behind staff aces Jack Taylor and Jake Weimer. As the season progressed, Wicker challenged the pair for staff supremacy, winning 11 of his last 13 decisions. A season-ending 10-3 win over Boston vaulted him into the 20-win club, joining Taylor (21-14) and Weimer (20-8). Including his one game with St. Louis, Wicker posted major-league career highs in wins, winning percentage (.690), innings pitched (252), and strikeouts (113), and figured prominently in team plans as the third-place (82-56) Cubs began an inexorable move up the National League standings.

In many respects, Wicker pitched even better the following season, even though his final won-lost record dropped slightly to 17-9 (.654). His ERA (2.67), opponents’ batting average (.232), and opponents’ on-base percentage (.282) were all lower than the year before, and he hurled four shutouts. One of them was the single best game of Bob’s career. On June 11, 1904, he faced the New York Giants in the Polo Grounds before a then-record crowd of 38,805 fans. His mound opposition was future Hall of Famer Joe McGinnity, the winner of his first 12 decisions and on the way to a superb 35-8 record. But McGinnity was not the equal of Bob Wicker that afternoon. For nine innings, Wicker no-hit the pennant-bound Giants, before finally allowing two scratch hits in extra frames. In the 12th, a Johnny Evers single plated the game’s only run and gave Wicker and the Cubs a 1-0 victory that ended McGinnity’s winning skein. What made “the best exhibition of [Wicker’s] baseball career”23 all the more remarkable was the fact that, when not taking his pitching turn, Wicker had been the Cubs’ everyday center fielder for the previous three weeks, filling in capably for an injured Jimmy Slagle.24 By season’s end, the 93-60 Chicago Cubs had climbed into second place, but were still well behind the Giants (106-47).

The 1905 season was a frustrating one for both Wicker and the Cubs. A bout with bronchitis kept Wicker out of action in the early going. When he was fit to return, a case of smallpox was detected in the Chicago apartment house where he lodged. Although not afflicted himself, Wicker was nonetheless quarantined for another two weeks.25 His 1905 debut was therefore delayed until June 4, when he dropped an 8-2 decision to Pittsburgh. Thereafter, Wicker quickly returned to form, throwing shutouts at Boston (7-0) and New York (1-0, over Joe McGinnity) in his next two starts. Restricted to 22 appearances, Wicker posted a fine 13-6 (.684) record, with another four shutouts and a career-best 2.02 ERA. But the Cubs pitching staff was changing, with the mantle of club ace now assumed by newcomers, 18-game winners Mordecai Brown and Ed Reulbach, while Wicker’s future with the team was soon in jeopardy.26 Chicago’s excellent 92-61 record had been good for no more than third place in 1905 NL standings, and new Cubs manager Frank Chance was anxious to make the personnel moves needed to put the club on top.

Wicker did himself no favors by reporting to 1906 spring camp overweight and out of condition.27 But he got off quickly once the regular season arrived, defeating Cincinnati 5-1 in the early going and winning his next two starts. Chicago sportswriter W.A. Phelon Jr. was delighted by this unexpected turn of events, observing, “It was supposed that Wicker would not be seen in action before May, as he was the fattest and least conditioned man on the team. Trainer Jack McCormick has done wonders with the bulky boy. Having Wicker in shape this early means a lot to the team.”28 But a series of poor outings followed, sealing Wicker’s fate with Chicago. With his record standing at 3-5 in ten games in early June, Wicker was traded to Cincinnati for Orval Overall (4-5). Now pitching for a mediocre Reds club, Wicker continued his slide. Two months later, it was reported that “Bob Wicker is being given rest which, it is hoped, will put him in good condition.”29 After a four-week layoff, Wicker returned to action, defeating Pittsburgh 2-1 on September 21, 1906. Unbeknownst to the winning pitcher, it would be his final major- league game. That winter, Cincinnati sold Wicker’s contract to the Columbus Senators of the Class A American Association, bringing his major-league career to a close. In retrospect, about the only highlight of 1906 for Wicker was an event that occurred off the diamond. On October 27, 1906, he and west-side Chicago native Alice Chapin were married at St. Paul’s Methodist-Episcopal Church in the bride’s hometown. Their union would endure for the next 49 years, but produce no children.

The following spring, a determined Wicker informed the sports press that “he is still good and says that he will make such a good showing in the minor leagues that some of the big league managers will have to either purchase him or draft him.”30 Although Wicker was only 30 years old, it was not to be. His major-league days were now behind him. In six seasons, he had posted a solid 64-52 (.552) record, with a 2.73 ERA in 1,036⅔ innings pitched. Wicker had completed 97 of his 117 big-league starts, and posted ten shutouts. He had also proved a useful outfield fill-in on occasion, batting .205 in 500-plus plate appearances and playing the field competently. When at his best in Chicago, he had been a dependable middle-of-the-rotation starter, but Wicker became expendable once the pitching staff came to feature the likes of Brown, Reulbach, Carl Lundgren, and Jack Pfiester. With Overall joining the pitching corps, the Cubs posted an all-time regular-season best 116-36 (.763) record in 1906, and then went on to capture NL flags in 1907, 1908, and 1910, and World Series crowns in 1907 and 1908. In the meantime, a 6-11 mark once with Cincinnati in the latter half of 1906 season (and 9-16 record combined) seemed to extinguish major-league interest in Wicker. He never received another big-league shot.

In 1907 Wicker posted a not-good-enough 14-12 record for an American Association pennant-winning (90-64) Columbus club and drew his release. He then signed with the Montreal Royals of the Class A Eastern League. Meanwhile, the success of Overall in a Cubs uniform (12-3 in 18 games in 1906, and 23-7 in 1907) had prompted recriminations in Cincinnati, with ousted Reds manager Ned Hanlon being roundly scored for trading rising star Overall for the short-tenured Wicker. Dueling press releases issued by a defensive Hanlon and a smug Frank Chance entertained baseball fans during the 1907-1908 hot-stove season.31 Wicker himself took no part in the debate. Rather, he focused on salvaging his pitching career. But before reporting to Montreal, Bob returned to the University of Indiana, where he coached the Hoosiers baseball team to a 7-9 record. Thereafter, he posted a creditable 15-11 log for a noncontending (64-75) Montreal team. In 1909 Wicker fell to 11-14 with another sub-.500 edition of the Royals. Released once again, Wicker’s career in the professional ranks seemed over.

The 1910 US Census places Bob and Alice Wicker in Bedford, Indiana, but no occupation is listed for either. The following spring, Wicker attempted a comeback, signing with the Louisville Colonels of the American Association. Like Wicker, Louisville manager Del Howard had attended Oak Ridge Male Institute in his youth, and he had later been signed by the Chicago Cubs on the recommendation of Bob Wicker.32 After Wicker was hit hard in a spring exhibition game against a college team from LSU, one news report stated that “old Bob Wicker hasn’t much of an arm left but still possesses pitching sense.”33 Weeks later, Wicker bested a fading Rube Waddell, then pitching for Minneapolis. But on May 26, 1911, Louisville released Wicker unconditionally.34

Unable to get the game out of his system, Bob returned to Bedford, where he pitched and managed a local nine. In 1912 he assumed the job of baseball coach at Rose Polytechnic Institute in Terre Haute, where his star hurler was future major-league standout Art Nehf. In 1913 Wicker guided a Bedford team to the Indiana state amateur baseball championship game, but lost to a club from Princeton, 6-0.35 The following year, he managed and pitched for a team from Kokomo, Indiana.36

On January 11, 1915, Wicker unexpectedly returned to Organized Baseball, signing on to manage the Spokane Indians of the Class B Northwestern League. West Coast sportswriters seeking a line on the unfamiliar new skipper were reassured by testimonials received from former Wicker teammates Joe Tinker and Johnny Evers. In a published letter, Evers described Wicker as “a very smart pitcher, a hard and earnest worker, and a good, clean-cut fellow. … [H]e is just the man you would pick out of thousands to lead a ball club.”37 Still, resentment lingered among many in the Fourth Estate, particularly those who had championed a local man named Reynolds for the Spokane post. A fast start put many would-be Wicker critics at bay, and Bob himself pitched well in the early going. Particularly gratifying was his 2-1 victory over Tacoma and old foe Joe McGinnity in mid-May. By August, Spokane (64-41) was cruising toward the pennant. Then suddenly, the team collapsed. An 18-1 loss to Vancouver on August 29 drew a bitter press denunciation of the Spokane effort, with Wicker accused of willfully permitting the game to degenerate into farce.38 By season’s end, Spokane (81-74) had tumbled to third place, and Wicker was soon dismissed, his departure occasioning an angry blast from the Seattle Daily Times: “Wicker quit cold and allowed his team to curl up like a worm. … The last time the Spokane team played here, it was licked before it started every game, and Wicker did not lift his head up once during the week.”39

Unloved in the Pacific Northwest, Wicker returned to friendlier surroundings. After going 13-15 in over 250 innings pitched for Spokane, the now 39-year-old was not yet ready to give up the game. He declined a return engagement in Kokomo, choosing instead to move back to Chicago and pitch for the Garden City club in the city’s fast semipro league. 40 Bob Wicker’s final press-worthy engagement came for Artie Hofman’s Premiers, pitching a benefit game for the Eighth Regiment at Comiskey Park against a famed black team, the Chicago American Giants.41 Thereafter, he seems to have finally hung up the glove.

When he registered for World War I military service, Wicker listed his occupation as an inspector for a Chicago tool manufacturing company. For the national census two years later, he reported a clerical job in a factory, while wife Alice worked as bookkeeper. Ten years later, Wicker was employed as a salesman in a Chicago retail store. As he grew elderly, Bob suffered from diabetes and heart disease. He died of congestive heart failure at St. Francis Hospital in Evanston, Illinois, on January 22, 1955. Robert Kitridge “Bob” Wicker was 77. After a funeral service in Chicago, his remains were interred in Forest Home Cemetery, Forest Park, Illinois. Survivors included his widow, Alice; brothers Bert and Leland Wicker; and sister Ruby Wicker Lee.

Acknowledgements

The writer is indebted to Joyce Shepherd, library director of the Edward L. Hutton Research Library, Lawrence County Museum of History, for supplying material related to the life of Bob Wicker and the Wicker family preserved in the archives of Bedford, Indiana, newspapers.

Sources

Sources consulted during research for this biography include the Bob Wicker file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; Retrosheet; The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 2nd ed., 1997); Wicker family tree information accessed via Ancestry.com, and newspaper reportage, particularly items published about the subject and his family in the Bedford (Indiana) Daily Mail. Statistics presented herein have been drawn from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 Aside from Wicker (20-8 for the Cubs, and 0-1 for the St. Louis Cardinals in 1903), Mordecai Brown (1906 through 1910), Ed Reulbach (1906, 1908), Jack Taylor (1902, 1903), Jake Weimer (1903, 1904), Orval Overall (1907, 1909), Jack Pfiester (1906), and King Cole (1910) won 20 or more games for the Chicago Cubs during the 1901 through 1910 seasons.

2 Baseball reference works are wildly inconsistent regarding particulars of Wicker’s life, differing on date of birth, year of birth, place of birth, height, and weight. Compare, for example, Total Baseball (7th ed., 2001): born May 25, 1877 in Bono, Indiana, with Retrosheet: born May 24, 1878 in Bedford, Indiana. Or Baseball-Reference (major league record section): 6-feet-2/180 pounds, with Baseball-Reference (bullpen section): 5-feet-11/210 pounds. In resolving biographical conflicts, primacy has been accorded information supplied by Wicker himself, like that contained on his World War I draft card application where he supplied under oath the birth date of May 25, 1877. Or information published contemporaneously, like the Wicker family obituaries published in the local newspaper, rather than in baseball reference works published decades after Wicker’s death in 1955. In this regard, news items published in the Bedford (Indiana) Daily Mail establish beyond peradventure that Bob Wicker was born and raised in Bono, not Bedford. As for Wicker’s size, a subjective assessment of Wicker photographs favors the tall-for-his-time and well-proportioned Wicker being the 6-feet-2/180 pounds listed in Baseball-Reference (major-league record section) over the stocky, Joe McGinnity-esque 5-feet-11/210 pounds published in Baseball-Reference (bullpen section). To muddle the issue further, sister Ruby Wicker Lee listed Bob as 6-feet-1/195 pounds in the player questionnaire that she submitted to the Hall of Fame sometime in the 1960s.

3 Bob’s known siblings included James Elmer (born 1872), John (1875), Bert (1882), Roscoe (1885), George (1886), Leland (1891), and Ruby (1894).

4 As reported in the Bedford Lawrence (Indiana) Mail, February 11, 1886.

5 Toddler brothers Roscoe (age 3, flux [dysentery]) and George (20 months, cholera) died within nine days of one another in July 1888. Older brother John (18) succumbed to pneumonia in March 1893, while oldest brother Elmer (29), a railroad conductor, was killed in a train accident in January 1902. Meanwhile, cousins John (13) and Everett (10) drowned when their decrepit fishing dinghy capsized in August 1897.

6 As per the player questionnaire submitted to the Hall of Fame by Ruby Wicker Lee.

7 As reported in the Bedford Daily Mail, February 21, 1890.

8 As later noted in Sporting Life, July 8, 1905, and the Winston-Salem Journal, March 19, 1911.

9 Wicker’s name was periodically mentioned in local press coverage of the Bedford team. See e.g., the Bedford Daily Mail, July 27 and August 11, 1894.

10 Bedford Daily Mail, July 27, 1895.

11 See e.g., the Bedford Daily Mail, November 1, 1895: killed 30 rabbits in a single day’s hunting; November 19, 1895: Walter and Bob Wicker knocked down 26 quail, “all in single shots”; May 5, 1898: Bob wins third place prize in a Bedford Gun Club competition; December 19, 1902: hunting quail with his uncles in Fort Ritner, Indiana; November 17, 1904, hunting quail near Elnora.

12 As reported in the Bedford Daily Mail, June 17 and September 24, 1896.

13 As noted in Sporting Life, August 7, 1898.

14 Evansville (Indiana) Courier and Press, August 29, 1898.

15 As reported in the Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, July 2, 1899.

16 Sporting Life, August 19, 1899. No statistics for the 1899 Indiana-Illinois League were found by the writer.

17 As reported in the Rockford (Illinois) Daily Register, September 22, 1899, and Sporting Life, September 30, 1899.

18 Sporting Life, October 13, 1900.

19 As subsequently recalled in the Bedford Weekly Mail, September 28, 1906.

20 As reported in the Cincinnati Post, August 12, 1901.

21 As per the Trenton Evening Times, September 3, 1901. Wicker had injured his arm while pitching for Dayton in a game against Indianapolis, according to the Bedford Weekly Mail, August 9, 1901.

22 As reported in the Cleveland Plain Dealer and Washington Post, June 27, 1902, and Sporting Life, July 5, 1902.

23 According to the Chicago Tribune, June 12, 1904.

24 Slagle had been out of the lineup since late May, nursing a spike wound to his arm. Wicker took his place in center for 20 games, “playing well in the outfield and hitting as good as Slagle did,” in the estimation of sportswriter W.A. Phelon, Jr. in Sporting Life, June 11, 1904. Later that month, Wicker broke a finger on his glove hand, bringing his stint as a Cubs outfielder to an end. For the 1904 season as a whole, Wicker batted .219, while posting a .939 fielding average in the outfield.

25 As per the Chicago Tribune, May 6, 1905, and Sporting Life, May 13 and 20, 1905.

26 Before the 1905 season began, Chicago manager Frank Selee had reportedly offered Wicker or right-hander Button Briggs to Cincinnati in exchange for pitching prospect Orval Overall, as per Sporting Life, February 18, 1905.

27 As reported in the Chicago Tribune, March 21, 1906, and Sporting Life, April 21, 1906.

28 Sporting Life, April 28, 1906.

29 Sporting Life, August 9, 1906. Although being “out of condition” was often sportswriter code language for drunkenness, the writer found no evidence that Wicker had a drinking problem.

30 As syndicated in the Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, February 17, 1907, Salt Lake Telegram, March 22, 1907, and elsewhere.

31 See e.g., the Chicago Tribune, February 18, 1908, The Sporting News, February 20, 1908, and Sporting Life, February 22, 1908.

32 In early 1904, Cubs manager Selee “signed a kid named Del Howard. … Bob Wicker recommended him and says that, for a beginner, Howard is a wonder.” Sporting Life, February 6, 1904. Outfielder Howard later batted .263 in a five-season major-league career.

33 Saginaw (Michigan) News, March 29, 1911.

34 As reported in the Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune and Grand Forks (North Dakota) Evening Times, May 27, 1911, and elsewhere.

35 As reported in the Evansville Courier and Press, September 29, 1913.

36 As per the Chicago Tribune, January 31, 1914, and Sporting Life, May 16, 1914.

37 Seattle Daily Times, February 10, 1915.

38 See the Bellingham (Washington) Herald, August 30, 1915: “Bob Wicker need never come back here with his alleged pennant cappers and expect a turnout to see the game.”

39 Seattle Daily Times, January 23, 1916.

40 As noted in Chicago Tribune, July 30, 1916.

41 Reported in the Chicago Tribune, August 17, 1916.

Full Name

Robert Kitridge Wicker

Born

May 25, 1877 at Bono, IN (USA)

Died

January 22, 1955 at Evanston, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.