Saul Davis

“Saul was a great man and one of my best friends. He was a pretty good player, quite a lady’s man, and one of the greatest people I ever met in my life. He was a good hitter and a good glove man. If things were like they are today, he would have played in the major leagues. A lot of us would have.”1

“Saul was a great man and one of my best friends. He was a pretty good player, quite a lady’s man, and one of the greatest people I ever met in my life. He was a good hitter and a good glove man. If things were like they are today, he would have played in the major leagues. A lot of us would have.”1

Those words were spoken by Bill Robinson, a longtime friend and former teammate with the Memphis Red Sox, shortly after Saul Davis died in 1994. Teammates from Davis’ playing days read like a who’s who of Negro League baseball. They included Satchel Paige, Rube Foster, Cool Papa Bell, Pop Lloyd, Mule Suttles, Willie Wells, and Turkey Stearns.

When asked by an interviewer to name best player he ever saw, without hesitation Davis said Josh Gibson. “He was not one of the greatest baseball players, he was the greatest! Old Josh could hit anything and hit it anywhere,” Davis said.2

Teammates and opponents from his barnstorming days also included stars from the white baseball world such as Babe Ruth, Cy Young, Grover Cleveland Alexander, Bill Dickey, and the Waner brothers. He even played against (and was struck out by) the most famous female athlete in the country, Babe Didrikson, in a tournament.

Outside of baseball, Davis crossed paths with some of the most famous people in twentieth-century America. He counted Fats Domino and Count Basie as friends. Saul said he was once a doorman for Al Capone in Chicago and had lived next door to Muhammad Ali. Country music singer Charlie Pride, who played in the minor leagues, and for the Memphis Red Sox and Birmingham Black Barons in the Negro American League in the 1950s, phoned Saul’s daughter to check on Saul’s health shortly before Saul died. Davis also claimed he met Britain’s Queen Elizabeth [the wife of King George VI and the mother of future Queen Elizabeth II] during the royals’ trip to Canada in 1939 when he was playing in a tournament in Portage la Prairie, Manitoba.3

Saul regretted the day he turned down the request of a fourteen-year-old kid to come to Minot, North Dakota, to play with him on a local team. That kid’s name was Willie Mays. Davis and Mays maintained a close friendship over the years. Mays paid to fly Davis to San Francisco for a roast held in Willie’s honor just a few years before Davis died.

According to Negro Leagues historian Larry Lester, Saul Davis is the person credited for discovering famed pitcher Satchel Paige. “Saul told Birmingham owner Jim Rush there was a fine pitcher from Mobile, Alabama, he should check out,” said Lester. “The rest is history.”4 Paige made several trips to Minot to visit Davis over the years.

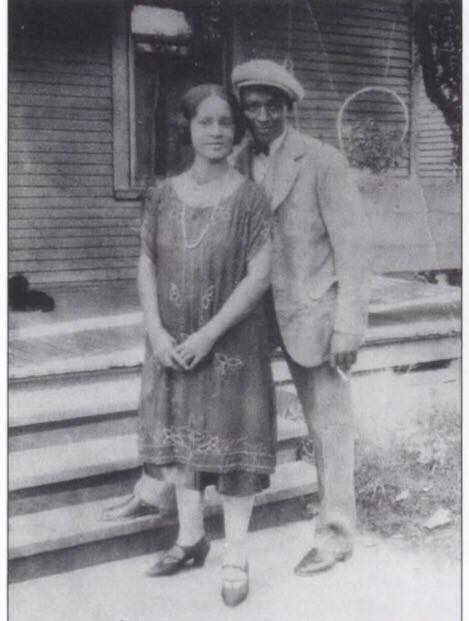

Saul Henry Davis Jr. was born February 22, 1901, to Cora Mae (Veaslay), a young woman of Creole ancestry, and Saul Davis Sr., a descendent of slaves. His father worked as a horse trainer, and was employed his entire life by a family named Wells.5 No official records were found about any siblings Davis may have had. He admitted to having a number of half brothers and half sisters and one full brother. A photograph dated 1922 shows Davis posing with a woman named Juanita Davis Beadle, who was identified as his sister,6 although she may have been one of his half sisters.

His birth date was never disputed, but there is some confusion about the location of his birth. One source said he was born in Monticello, Arkansas,7 another in Bayou, Louisiana,8 and still another in Bogalusa, Louisiana.9 According to his obituary, his birthplace was Little Rock, Arkansas.10 No birth record was ever located. Saul, in later years, said he was born in Louisiana.11 Given his mother’s Creole ancestry, and his references to playing in the swamps in the bayou as a young boy, it is likely that he was born in and grew up in Louisiana.

He attended school through the seventh grade at the Monticello Academy, a private boarding school for black students in Monticello, a small town in southeast Arkansas. Under the sponsorship of the Presbyterian Church, the Academy was originally established in the late 1800s to provide educational opportunities for freed slaves in the South. When he wasn’t in school, young Saul spent his time among the cypress trees and snakes in the swamps of the Louisiana bayou near his home.

He attended school through the seventh grade at the Monticello Academy, a private boarding school for black students in Monticello, a small town in southeast Arkansas. Under the sponsorship of the Presbyterian Church, the Academy was originally established in the late 1800s to provide educational opportunities for freed slaves in the South. When he wasn’t in school, young Saul spent his time among the cypress trees and snakes in the swamps of the Louisiana bayou near his home.

About the time he was fourteen or fifteen years old he quit school, left home, and made his way to Hot Springs, Arkansas. Saul found work as a bellboy and began shagging balls at the local ballpark where the Boston Red Sox and Philadelphia Phillies came for spring training. He soon caught on as a shortstop with the Hot Springs team in the Arkansas Negro League called the Vapor City Tigers.

The next year, probably 1918, Davis got a call from the Houston Black Buffaloes of the Negro Texas League. He remained in Houston until 1921 when he joined the Columbus, Ohio, Buckeyes in the Negro National League (NNL). His whereabouts in 1922 are unknown, but possibly he was back in Houston.

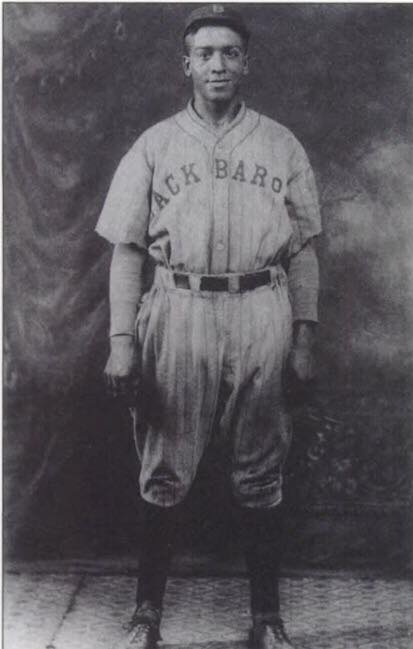

According to baseball-reference.com, Davis did not play for Birmingham until 1925, but other sources indicate he joined the Black Barons as early as 192312 and played part of four seasons, through 1926, in Birmingham.13 There were reports that he may also have been playing in the Eastern Colored League for a time, but no information to substantiate that could be found.

There are many discrepancies in records of his playing career. Between Davis’ conflicting stories told in interviews, his difficulty in recalling details from his playing days fifty years earlier, differences in oral accounts told by others, and often incomplete and unreliable Negro league records, an accurate account of his playing career may never be available.

Davis hit .328 for the Black Barons in 1925, and he claimed Rube Foster came to Birmingham to recruit him for the Chicago American Giants. Davis said he was a member of the Giants championship team in 1926 and that he beat out a player named Bobby Williams for the starting shortstop job.14 However, Williams was on the Chicago roster all during 1926, and there is no record of Davis having played for the Giants that season.

Rather, Davis spent the 1926 season with the independent Memphis Red Sox and remained with that club in 1927 when they joined the NNL. He split the 1928 season between Memphis and the Cleveland Tigers. In 1929 Davis did play with Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants. He began the 1930 season with Chicago, but finished with Memphis. He was with the Detroit Stars in 1931, his last season in the NNL.

Batting and fielding statistics that are available for Davis are consistent with his own assessment of his career. He was a 5-foot-11, 185-pound right-handed-hitting infielder, primarily a shortstop, with a slick glove and strong arm. Davis was a slap hitter with little power, would rarely strike out, and tried to punch the ball over the infield for singles and an occasional double. He used a bottle bat, the model made famous by major leaguer Heinie Groh.

After his NNL career ended, Davis joined the Gilkerson’s Union Giants, a top Black traveling club. In the early 1930s he traveled around Canada with his baseball gear and a uniform in his car trunk, showing up at tournaments and asking teams if they needed any players. He played against Chicago “Black Sox” players Hap Felsch and Swede Risberg and their teams several times.

In the late 1930s Davis said legendary second baseman Bingo DeMoss and promoter Abe Saperstein asked him to become player-manager of the Zulu Cannibal Giants, a traveling team that wore grass skirts and dressed up to appear like savages from an African tribe. Davis enjoyed the experience as the team often traveled with Olympic sprinter Jesse Owens, who would take on the fastest runners local teams could come up with. “They thought Negroes in broken down trucks were easy pickings,” Davis said.15 Of course Owens won every race, picking up needed extra cash from the side bets that were placed.

The team drew great crowds throughout the Upper Midwest and Canada. Davis was left behind by the team when it left Minot, North Dakota, during one of the team’s barnstorming tours. Although the exact details of the team’s abandonment will probably never be known, the prevailing story was that Saul had gone drinking with three locals after a game and couldn’t be found when the team had to hit the road for their next game. No one who knew Saul doubted this story, since he was famous for some legendary drinking binges. Years later Minot reporter Dave Dondeneau repeated a story that dogged Davis throughout his life. “When he [Davis] went on one of his binges,” Dondeneau wrote, “the police never sent just one officer, they sent a bunch.”16 Davis decided to continue his baseball career in Minot, where he lived the rest of his life, playing with the Minot Merchants, the Minot Legionnaires, and other local teams until he was in his fifties.

Saul’s initial adjustment to Minot was difficult but he eventually prospered. Over the years he operated three restaurants in town, including “Saul’s Barbecue” from 1943 to 1962. Davis was also involved with other enterprises in Minot’s red-light district, including bootlegging and “hosting” young ladies. By Saul’s account he was “not really” arrested forty-two times for his business dealings and more than once fled to Canada when there were warrants out for his arrest. He once hid in the back of an ambulance, covered by a sheet, as police scanned the area for him.

In 1954 Davis was convicted in federal court in Minneapolis of violating the white slavery act, having been found guilty of two counts of transporting women from Minneapolis to Minot for the purpose of prostitution. He was sentenced to a four-and-a-half-year prison term. Davis appealed the ruling, alleging that some of the testimony in his trial was not properly admissible. He lost the appeal, but it is not known if he ever served any time in prison.

Davis mellowed as he got older. In 1974 he was honored by the mayor of Minot, and awarded the “Outstanding Citizen” award for his distinguished service to the community. As a senior citizen, he went to work for Green Thumb, a community program for seniors that allowed him to keep active watering flowers and landscaping until he was in his late eighties. His ninetieth birthday party in 1991 was a celebration attended by more than a hundred friends and well-wishers.

Davis continued to follow baseball but said, “I don’t like the game as much today. Why do they wear those iron helmets? If you ain’t got the sense to get out of the way of the pitch, then you ain’t got no business in the box. In my day we had pitchers that threw twice as hard and we’d never think of using an iron hat. It’s not right.”17

By his own admission, Davis was an “outlaw” during his playing days. He had no permanent home, frequently moving from place to place, often on a freight train. He spent what little money he made playing ball as fast as he could earn it, and took any odd job he could find in the offseason to get by until the next year. Davis worked, at various times, as a machinist, a chauffeur, and a waiter, sometimes in fancy hotels, and at other times on railroad dining cars.

His personal life also reflected his vagabond, live-for-today, lifestyle. A record was found of a marriage between a man named Saul Davis (age eighteen) and Marguerite Brooks (also eighteen) on May 8, 1919 in Monticello, Arkansas. No conclusive proof was found that this Saul Davis was the ballplayer, but Monticello, Arkansas, is where he went to school as a teenager, and he may have returned there in the off-season. The age of the groom is also consistent with Saul’s 1901 birth date.

In the 1920 U.S. Census, Marguerite and Saul Davis, now both twenty years old, were listed as being married and lodgers in the home of John and Ivory Gibson in Little Rock, Arkansas, where Saul was playing ball at the time. Saul Davis is absent from the 1930 Census, but Marguerite Davis was living as a lodger in Lake Providence, Louisiana, and now single. However, no other record of this marriage, or any subsequent divorce, was located.

That may have been the first of at least three marriages for Davis. He also said that when he was twenty-three years old he married a woman from Chicago he met in Birmingham. He said they had a daughter and that they were married six or seven years.18 This would have been about 1924, consistent with the time Davis said he had joined the Black Barons. However, no record of this marriage, or birth of a daughter, could be found.

Finally, after his move to Minot, Saul married Ann Tate on September 7, 1938. They had been married thirty-four years at the time of her death in 1972. Saul was proud of the fact that, despite his occasional brushes with the law, the people of Minot treated his wife royally, always calling her “Mrs. Davis.” They had one daughter, Charlene, born January 7, 1950, in Minot.

Davis died of cancer at his home in Minot on February 8, 1994, at the age of 92. At the time of his death, Davis was the oldest surviving member of the original Negro National League [1920-1931]. He was survived by his daughter, three grandchildren, six great-grandchildren, and one great-great-grandchild, and was buried at Rosehill Memorial Park in Minot.

Shortly before his death Davis said “I have a lot of great friends in Minot. I’ve met a lot of important people and had some great times. The good Lord was looking out for me when he left me in Minot. Being left behind was the best thing that ever happened to me.”19

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the endnotes, the author accessed clippings from Davis’ file at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, Kansas City, Missouri, and the following sites:

http://www.baseball-reference.com

US Census Bureau, 1920 US Census

US Census Bureau, 1930 US Census

Photos of Saul Davis in baseball uniform and Saul Davis with his sister, Juanita Davis Beadle, are courtesy of his granddaughter, Rebecca Kai Dickens.

Notes

1 Dave Dondeneau, “Davis Leaves Minot with Memories: Former Negro League baseball player dies at age 92,” Minot (ND) Daily News, February 10, 1994.

2 Carl O. Flagstad, “Davis Keeps Busy as he Reaches 90”, Minot (ND) Daily News, February 22, 1991.

3 Kyle McNary, “Negro Player of the Month, April 2003,” http://www.pitchblackbaseball.com/nlotmsauldavis.html, accessed May 6, 2014.

4 Dave Dondeneau, “Living for the moment for more than 91 years,” Minot (ND) News, February 10, 1994.

5 Richard Bak, Turkey Stearns and the Detroit Stars: the Negro Leagues in Detroit, 1919-1933, Chapter 9, “Saul Davis: The Way it Was” (Detroit, Wayne State University Press, 1995), 165.

6 Larry Lester, Sammy J. Miller, and Dick Clark, Black Baseball in Detroit (Chicago, Arcadia Publishing, 2000), 66.

7 “Saul Davis Minor League Statistics & History,” http://www. baseball-reference.com/minors/player.cgi?id=davis-000sau, accessed May 6, 2014.

8 McNary, “Negro Player of the Month, April 2003.”

9 E-mail from Larry Lester, SABR Negro Leagues Committee, October 17, 2013.

10 Saul Davis obituary, Minot (ND) Daily News, February 11, 1994.

11 Bak, Turkey Stearns and the Detroit Stars, 165.

12 Ibid, 166, 168.

13 Larry Powell, Black Barons of Birmingham: The South’s Greatest Negro League Team and Its Players (Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland Publishing, 2009), 14.

15 Dondeneau, “Living for the moment for more than 91 years.”

16 Ibid.

17 Dave Dondenau, “Davis was a man who touched a lot of lives”, Minot (ND) Daily News, February 10, 1994.

18 Bak, Turkey Stearns and the Detroit Stars, 171.

19 Dondeneau, “Davis was a man who touched a lot of lives.”

Full Name

Saul Henry Davis

Born

February 22, 1901 at Monticello, AR (US)

Died

February 8, 1994 at Minot, ND (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.