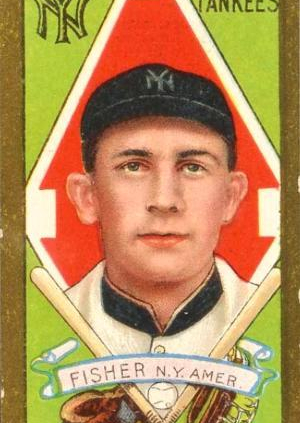

Ray Fisher

[With research assistance from John Leidy]

[With research assistance from John Leidy]

Ray Fisher has been justly honored for his 38 seasons as head baseball coach at the University of Michigan. He was elected to Michigan’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1959, the American Association of College Baseball Coaches Hall of Fame in 1966, and the University of Michigan Hall of Honor in 1979. And on May 23, 1970, he received his greatest honor when the ballpark at the University of Michigan was renamed Ray Fisher Baseball Stadium.

Yet although his name is almost as revered in Ann Arbor as “Hail To The Victors,” Michigan’s famous fight song, Ray Fisher is nearly forgotten in his native Vermont. Even though Fisher spent each summer in a camp on Lake Champlain, few Vermonters remember the fine major-league pitcher who compiled a 2.82 ERA and won 100 games over ten seasons prior to his unjust banishment by Commissioner Landis in 1921.

Ray Lyle Fisher was born on a farm in Middlebury, Vermont, on October 4, 1887. His two oldest brothers worked their entire lives as farmers, and Ray appeared to be destined for a similar fate. “My parents only let me play sports if I kept up my share of the farm work,” he recalled.

Ray was a star pitcher for Middlebury High School, and following his graduation in 1906 he received an offer to play semi-pro baseball in Valleyfield, Quebec. Ray’s father expected him to work on the family farm, however, so Ray was allowed to play only on condition that he send enough money home to hire a farmhand. He did so and had plenty to spare, earning his room and board and $10 per week for pitching, and an additional $1.35 per day as a machinist’s assistant at the Dominion Textile Factory.

That fall Ray joined his older brother Harry as a student at Middlebury College. The youngest Fisher excelled in collegiate athletics, setting the school shot-put record and playing varsity football and baseball. “Pick” (short for “Pickerel”), as he was called by schoolmates, was an infielder at Middlebury until Cy Stackpole, an old minor leaguer who coached the varsity, turned him into a pitcher. Fisher remembered that day:

“Go out on the mound and throw me a few,” Cy said one day in practice. So I went out, tried a curve or two when Stackpole, standing in the box with a bat, told me to. Then I up and threw a fastball. It zipped pretty good. Stackpole just stood there looking at me for a long time with a half-smile on his lips. Finally he said, “How’d you like to pitch against Colgate tomorrow?” I said fine. Colgate, of course, was a major baseball power and was expecting to mop us up. But I had quite a day, fanned 18 and shut them out.

Before long scouts took notice of the 5’11”, 195 lb. right-hander. The summer between his sophomore and junior years at Middlebury Fisher signed with Hartford of the Class-B Connecticut State League. In his first partial season as a professional, he went 12-1 as a starter and reliever, and his .923 winning percentage stood as a minor-league record for over half a century.

In 1909 Ray returned to the Connecticut capital and registered one of the greatest minor-league pitching performances ever, going 24-5 with 243 strikeouts to lead Hartford to its first-ever pennant. By that point major-league teams were interested in his services. Ray signed a $1,500 contract with the New York Highlanders (later known as the Yankees) on condition that he be allowed to return to the Middlebury campus for his senior year. He signed with New York thinking he would not receive other offers, but shortly thereafter Ray Collins told him that the Boston Red Sox also wanted to sign him.

After graduating from Middlebury in 1910, 22-year-old Ray Fisher reported to New York carrying, to the amusement of his new teammates, a homemade bat he had whittled himself back at his Vermont farm. Despite his naivety, Fisher was unimpressed by his new surroundings. “They called it Hilltop Park,” he said, “and it wasn’t even a good college field. The foul lines were cockeyed and the outfield sloped downhill, so when the batter hit one out there it actually rolled toward the fences.”

New York manager George Stallings gave his new pitcher a start against the Chicago White Sox on July 2. Years later Fisher remembered one game during that first season:

My opponent was Ed Walsh, a great pitcher, and Stallings figured he was going to lose the game and didn’t want to waste one of his regular pitchers so he put me in. To be sure I wouldn’t hurt any of his regular catchers — I was a bit wild, no doubt — he brought out Lou Criger, who was the famous batterymate of Cy Young. I think my first game in the majors was his last.

Ray went on to trim the White Sox by a score of 2 to 1, and Stallings told him later that he never would’ve started him if he’d thought the Highlanders had a chance to beat Walsh that day.

Later in the 1910 season Stallings was replaced as manager by first baseman Hal Chase, one of the most unsavory characters in the history of the game. Fisher remembered Chase as a “wonderful fielder, wonderful ballplayer,” but he also thought the manager was a kleptomaniac. “If we were playing poker, he’d play,” Fisher said. “But if he weren’t playing, he’d sit right down next to you and see what you needed and he’d try to hand you the cards so you would cheat. Good fella, but just wanted to do things that weren’t right.”

Surprisingly, Fisher initially thought more highly of Chase than of Hall-of-Fame manager Frank Chance, who led the Yankees in 1913 and 1914. “He didn’t know any of us,” Fisher said, “but he had that book [containing statistics from previous seasons]. When you were working, he sized you up and then he would look in the book and see what you did and then he would decide the reason. He was a devil.”

Relations between Fisher and Chance were strained until an incident during the 1913 season. “At that time I was ready to fight back a little bit,” Fisher remembered.

One day I was pitching and they hit a ball back to me with a man on first and I hesitated on my play. I wasn’t sure if Peck or Hartzel was covering so I only got one man. They would have gotten me out of the inning.

[Chance] hollered something at me and I hollered something back. Then I saw him making room for me on the bench. And I’m telling you we had it out. People in the boxes were leaning all over and listening. In the meantime, the inning was going. He was so intent on me he forgot to have any pitcher warmed up to take my place.

When the inning was over he didn’t have any pitcher warmed up. He said, “Do you want to pitch?” And I said, “I don’t give a damn if I ever pitch another game.” He said, “Go out there and pitch.”

The argument actually improved Ray’s standing with his fiery manager:

[Chance’s] second year I reported [for spring training] in Houston and there was a boy who went to school with me in Middlebury who lived outside of Houston. They invited me out and I didn’t know whether I would be home in time [for curfew]. I said to him, “I’m going to so-and-so’s and I expect to be back in time, but I want you to know where I’ll be.”

And he said, “No rules for you this year,” and that was it. He decided I was an alright guy. Never said boo to me. If I didn’t come to the ballpark the day after I pitched, no questions asked. Never a better manager than Frank Chance, once we got to know each other.

Fisher responded to the freedom with his best season to that point — 10-12 and a 2.28 ERA in 209 innings for the sixth-place Yankees in 1914. The next year, after Chance was forced into retirement by ill health, Ray pitched even better, going 18-11 with a 2.11 ERA (fifth-best in the A.L.).

Until then Fisher had spent his off-seasons in Vermont, serving as athletic director at Middlebury College. He had also taught Latin, and for that reason sportswriters had dubbed him “The Vermont Schoolmaster.” During the 1912 off-season he had married Alice Seeley, another Middlebury native, and they remained happily married until Alice passed away in 1976.

But by 1915 Ray was so popular in New York City that the president of Middlebury College thought he could do more for the school by spending his winters in Gotham. The loyal alumnus agreed; and one might speculate that but for the president’s “wisdom,” Ray Fisher might have spent the next half-century at Middlebury rather than Michigan.

Ray Fisher pitched for the Yankees through the 1917 season when he came down with pleurisy, a disease related to tuberculosis. He suffered with pain, shortness of breath and a weakened overall condition that finally caused him to miss more than one month of the season. His opponent on the day he returned was Walter Johnson, perhaps the greatest pitcher of all-time.

“He threw a fastball by me and, I’ll tell ya, it looked to me like he just opened his hand and it went by me,” Fisher said. “Then he threw me a curveball and that was just right for me. And I got to second and the second baseman said, ‘What did he do, throw you a curveball?’” What Fisher omitted in telling that story is that he threw a shutout that day to beat Johnson, 2 to 0.

Ty Cobb is known primarily for the anger and violence with which he played the game of baseball, but Ray Fisher saw a sweeter side of the Georgia Peach:

Although they say a lot of things about him, I remember distinctly in Detroit that he swung at a ball towards first base and I had to go cover. The ball was real slow along the foul line and I was trying to get the bag and catch the ball at the same time. I ended up with my leg across the bag. He could have stepped on it, and had the perfect right to, but he jumped the bag! If his reputation were true, he would have stepped on it and cut my leg.

Cobb (as did Napoleon Lajoie) listed Fisher among the toughest pitchers he ever faced, and Ray remembered one particular relief appearance in New York when he tamed the Tigers:

It was the eighth inning and [Ray] Caldwell got hit with a liner and split his hand. They put me in there and [Detroit] had the top of the order up. I fooled around and gave a base on balls to Donie Bush, and then Vitt pushed him over. I had Cobb and Crawford coming up.

I could pitch [to Cobb] if I had my stuff, ’cause he stood right on the plate. I got two strikes on him — you couldn’t have shot them in any better. I had slippery elm in my mouth and when I saw that second one go by, I put that spit on there and he never knew it. No one ever told him. He swung for a fast one and missed. I could have lost the game then and people still would have been for me! I will always remember that as a highlight because they had the tying run on second base and I got [Cobb] with three pitches.

[Then] Crawford grounded out to short. I remember I came up to bat — the umpires in those days were really good fellas. I remember as I came to bat — you wouldn’t hear it now — that ump said to me, “Ray, you’ve got pretty good stuff out there today.” They wouldn’t say that now, or even think of it.

Ray Fisher missed the entire 1918 season when he was drafted into the army. At the time he felt his military service was a colossal waste of time, but years later he reflected that perhaps it saved his baseball career. Rather than spending April through October traveling the country in smoke-filled trains, eating poorly and getting little rest, Fisher regained his health under the watchful eye of army physicians at Fort Slocum outside New Rochelle, New York. Ray used his managerial skills to run the camp’s athletics program.

While he was in the service Fisher was acquired by the N.L.’s Cincinnati Reds, who lowered his salary from $6,500 to $3,500. To make things worse, switching leagues meant that he had to learn how to pitch to a whole new set of batters, including Hall-of-Famer Rogers Hornsby:

In the first game I pitched in the National League against St. Louis, I bumped into Hornsby. I looked at him and decided to keep it away from him. [My pitch] was up pretty near waist-high. If it had been a little lower, I don’t know that he would have hit it the same, but he hit that thing over Greasy Neale’s head and it went to the fence.

But Cliff Heathcote was on first. He could run, but he wasn’t very sharp baseball-wise. Heathcote went past the shortstop and about when he got there, something hit him and he decided the ball had been caught and he turned around. Hornsby was about two-thirds of the way to second base and he stood there holding his hat, cussing the guy. We got the ball and got a force out.

The Reds caught a lot of breaks in 1919, and in his return to professional baseball Fisher was 14-5 with a 2.17 ERA as the Reds won their first-ever N.L. pennant. Cincinnati had a strong team built around Heinie Groh and Hall-of-Famer Edd Roush, but their World Series victory over the Chicago White Sox will be forever tainted by the Black Sox scandal. Fisher, in fact, was the losing pitcher in the famous Game Three when “Honest” Dickey Kerr beat the Reds on a three-hit shutout.

“No, we didn’t know some of the White Sox players had agreed to throw the Series,” Fisher said, “but I am sure some of our men knew there was something wrong as the Series progressed.” The most famous of the conspirators was Shoeless Joe Jackson. Fisher said of Jackson:

He wasn’t educated and the guys used to pull tricks on him, especially his own guys. He couldn’t read or write and they used to read his wife’s letters for him and, of course, they made stuff up.

The two men had developed a friendship, visiting before ball games, and Ray always believed that Joe was just too simple and naïve a man to get involved in something as complicated as throwing a World Series.

Prior to the 1920 season the National Commission decided to ban the spitball. Fortunately for Ray, the leagues allowed pitchers who already used it to continue for the rest of their careers, and he was one of 17 who were exempted from the new rule. Ray returned to the Reds, embittered that the team did not raise his $3,500 salary despite his fine performance in 1919. Still he pitched well (2.73 ERA), though the Reds faltered and his won-lost record sank to 10-11.

By 1921 Fisher’s daughter, Janet, was nearing two years old. Ray was beginning to grow tired of the nomadic life of a baseball player. He decided it might be time to settle into a “real” job. What happened in the spring of 1921, however, is not entirely clear, even to the individuals involved. What is clear is that Fisher left the Cincinnati club that spring and never again played in the major leagues.

While returning from spring training in Texas in March 1921, Ray Fisher learned that Del Pratt, formerly of the Browns and the Yankees, had declined the position as baseball coach at the University of Michigan to return to the major leagues. The previous year St. Louis Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey, an influential alumnus of Michigan Law School, had recommended Fisher for the position.

Ray spoke to Reds manager Pat Moran about interviewing for the Michigan job. Cincinnati management was aware that the Vermonter was unhappy with his salary and did nothing to prevent him from leaving the club. After pitching the last five innings and driving in the winning run in the Reds’ final exhibition game in Indianapolis, Ray drove to Ann Arbor to interview. The press reported that Fisher had been given his release with the expectation that he would accept the coaching position at Michigan.

Michigan offered the job to Ray, but around the same time two of Cincinnati’s better pitchers were not performing well. Moran suddenly became interested in keeping Fisher; newspapers quoted him as saying, “Ray is pitching better than he ever has.” But Reds owner August Herrmann refused to offer Ray a multi-year contract, and Fisher turned down a one-year contract with a $1,000 raise. With the parties at an impasse, Ray picked up the phone on Herrman’s desk and called Michigan to say that he’d take the coaching position..

In late April 1921, Herrmann dashed off a letter to N.L. President John Heydler expressing his dismay that Fisher had quit the Reds despite a salary increase. More importantly, the owner noted that his recalcitrant pitcher had given only seven days’ notice of his intention to quit — not the proper ten days’ notice as required by his contract. Heydler placed Fisher on the Ineligible List.

Ray was shocked when he heard the news. When his Michigan team was in Chicago, he sought out Commissioner Landis for a face-to-face meeting to learn his true status. Landis contacted Cincinnati manager Pat Moran for a full report of the dealings between the Reds and Ray Fisher. Had Moran permitted Fisher to interview for the Michigan position?

Moran responded, “I positively refused to grant [such permission] and told him to take up the matter over long-distance telephone with President Herrmann, which I understand he did not do, but took it upon himself to leave the next day.” For 30 years Fisher remained ignorant of Moran’s response, which he vehemently contested.

In June 1921, Commissioner Landis sent Fisher a telegram informing him that he had joined baseball’s Permanent Ineligible List. He remained on that list for nearly 60 years.

At the University of Michigan Ray Fisher became the dean of college baseball coaches. In nearly 1,000 regular season games, 1921 to 1958, Fisher’s teams went 661-292 (.694), won 14 Big Ten titles and an NCAA championship in 1953, the year he was voted NCAA Coach of the Year. Nearly 20 of his players went on to the major leagues, including Dick Wakefield and Don Lund. Fisher was Michigan’s winningest coach in any sport for 70 years, 1930-2000, until softball coach Carol Hutchins got her 662nd win. (As of 2006, Hutchins’s record stood at 961-360-4 for a .727 winning percentage.

Like the major leagues, collegiate athletics had returned to segregation around the turn of the century, but Fisher integrated his Michigan team long before it became normal practice. He also played a role in popularizing baseball in Japan by taking teams to Tokyo in 1929 and 1932 to play exhibition games against Meiji University.

Returning to his family’s camp on Lake Champlain during summers, Ray became one of the driving forces behind semi-pro baseball in Vermont. Occasionally he pitched for the team from Long Point, where his camp was located, or for Vergennes, as on this occasion described in the September 10, 1934, edition of the Burlington Free Press:

Ray Fisher, a 47-year-old veteran of the majors, pitched himself into the local baseball hall of fame here this afternoon with a no-hit, no-run victory over the Queen City Blues team of Burlington…. [H]e leaves tonight to resume his coaching duties at the University of Michigan…. Today’s game was played in the remarkably short time of 55 minutes, so easily did Fisher dispose of the opposing batsmen.

But he is best-remembered as the fiery manager of the Twin City Trojans of Vermont’s famous Northern League. Ray Fisher stood up for the rights of college baseball players to further their skills and earn extra money by playing in summer leagues, especially in light of the numerous scholarships available to football and basketball players and the flexibility of the amateur status of track teams. Baseball players, he felt, were treated unfairly. To his frustration, the Big Nine had strict rules on player eligibility, and much of Ray’s final years in collegiate coaching were spent fighting with the NCAA.

With his national reputation, Fisher had little difficulty attracting top players to the Northern League, but the best player he ever coached was undoubtedly Robin Roberts. Though the future Hall-of-Famer pitched for rival Michigan State, Ray somehow convinced him to play for the Twin City Trojans in 1946 and 1947. Roberts has fond memories of his time in the Green Mountains, particularly the second season: “[W]e were really good then. I won 17 straight starts that year in Vermont, and that was the year the scouts became interested. I signed with the Phillies in September of that year and was in the big leagues the next June.”

To the chagrin of his coaches at Michigan State and Philadelphia, Robin Roberts consistently credited Ray Fisher for his success: “Ray taught me everything,” he said. “Everything I’ve been told by the Phillies coaches is just a repetition of what I learned in Vermont. Of course, it’s nice to be reminded, and don’t think I don’t appreciate the help I’ve received from fellows like [George] Earnshaw and [Schoolboy] Rowe. It is just that I feel I owe so much to Fisher.”

With players like Roberts, Fisher’s Montpelier-based Twin City Trojans were always the team to beat, and his rambunctious coaching style brought out the fans. While he was tough on umpires at Michigan, his school-year persona didn’t compare to the summer character known as “Angry Ray” (or “Rowdy Ray,” “Violent Fisher” or “Cry Baby Ray,” to mention a few of the nicknames he received from the Vermont press).

Ray was consistently tossed out of games and frequently required the assistance of police officers — not only to get him to leave the ballpark, but to protect him from rowdy fans once he got outside. Though sometimes his tirades were marked by equipment-tossing and protested games, Ray generally limited his actions to pointed verbal abuse — but never any expletives.

One story is recounted by R.W. Manville, a former Northern League player, in a letter written in May 1970:

One night, after a particularly harrowing series of umpires’ bad decisions, Ray managed (with a few “Lord-a-mighties!” thrown in) to get himself excused from the game in the fifth or sixth inning. In his easily recognizable yankee-spiced voice, he soon had everyone in the stands in arms over his comments wafting gently from somewhere behind the clubhouse. This ultimately led to disaster, and my final remembrance of that evening is Mother Fisher standing by her car, all four tires having been deflated by the crowd, asking the team to go rescue Ray from the clubhouse. As we surrounded him, bats in hand, on leaving the park, Ray couldn’t resist one more fling at the hostile crowd: “This is a five-cent town, three-cent team, and a penny’s worth of umpire!”

Much of that behavior was an act, as demonstrated in this excerpt from the Burlington Free Press:

[Ray] went striding out to the plate umpire at Centennial Field one day after a close play, his hands shoved into his pockets like Casey Stengel. He waved his arguing player into the dugout.

Then, with outthrust jaw, he harangued the umpire. Once in a while he waved an arm while the crowd hooted and yelled. He whirled and went back to the dugout, the umpire glaring at him. After the game, we asked the umpire what Ray had said and got this answer:

“In a quiet voice, despite his arm swinging, Ray said, ‘I want you fellows to come down to my camp and we’ll have a cookout. We can get some fishing in there.’ Then he turned and walked away.”

A huge uproar followed Fisher’s resignation as coach of the Twin City Trojans in the middle of the 1949 season. At the time Ray was feeling the pressure of coaching year-round, and at age 62 he was enjoying more and more the time he spent on Lake Champlain. Fisher and the local media, however, focused on an ongoing problem Ray was having with a particular umpire.

The umpire had ejected Fisher from three contests, even though the rules of baseball were on Ray’s side on at least two of those occasions. Finally, after his appeal to the league commissioner failed, Ray decided to call it quits in midseason, citing a conspiracy against him. A more subtle reading of his actions indicates that he was ready to retire at the end of the season and preferred to go out in controversy.

Fisher never returned to managing in the Northern League, though he did spend a few summers coaching a semi-pro team in Blacks Harbor, New Brunswick, Canada.

Ray Fisher coached at Michigan until 1958, when his age forced him into mandatory retirement. While he continued to provide guidance in an unofficial manner, that year marked the beginning of his slow departure from the game he loved. Ray spent much of his retirement fishing and relaxing at his camp on Lake Champlain. There were still plenty of chores, and a Saturday morning was as likely to find Ray on his roof repairing shingles as baiting another hook.

Two events transpired in Ray Fisher’s later years that brought closure to his life in baseball. Back in the ’30s he had received a Lifetime Pass from the major leagues, which he interpreted to mean that his banishment from Organized Baseball had been lifted. He probably never thought twice when he worked as a spring training instructor for the Detroit Tigers and Milwaukee Braves during the early ’60s.

In truth, however, he remained on baseball’s blacklist, a fact that became apparent to Fisher when University of Michigan history professor Don Proctor wrote a wonderfully complete and compelling analysis of his banishment. But when numerous letters were written on Ray’s behalf to the Baseball Commissioner’s Office (including one from President Gerald Ford, who had played freshman football under Ray at the University of Michigan), Bowie Kuhn responded that baseball considered Fisher a “retired player in good standing.”

Then in the summer of 1982, just short of his 95th birthday, Ray attended an Old Timers Game at Yankee Stadium even though by that point he was confined to a wheelchair. Ray’s grandson, John Leidy, remembered the occasion:

When we got there the first evening, there was a reception and I was taken aback by the sheer number of the old-time players who were there. Many Hall-of-Famers: Mickey Mantle, Joe DiMaggio, Whitey Ford, Lefty Gomez. As a bystander, I was a little disappointed that almost none of the others went out of their way to speak to my grandfather.

Of course, to be fair, almost none of them knew him. None of them had played with him. Next to my grandfather, the oldest player there was Joe Sewell and I believe he went back to the ’20s. Grandpa was the only person there who had played in the teens.

I may be reading into this, but I also felt that those guys had a hard time relating to someone who was as old and as crippled as he was. I felt that these athletes were proud of their physical conditions and maybe it was difficult to accept the fact that they would age themselves.

Lefty Gomez came across the room right away and Joe Sewell spoke to him, too. But I will be forever in debt to, and appreciative of, Joe DiMaggio. He was the only person who had not previously known my grandfather who came over and paid his respects.

When we first arrived at Yankee Stadium and stepped out of the limousine, all these youngsters came up wanting autographs. We were in the dugout and they introduced the players one at a time, out on the line, all suited up. Of course my grandfather couldn’t play, but they introduced him as the oldest living Yankee, and they wheeled him out onto the field. He waved to the crowd and they had a long, loud standing ovation, second only to DiMaggio. Grandpa began to break down as the crowd was cheering. I saw the look on his face as he began to get teary as the cheering increased.

We had a dinner Saturday after the game and my grandfather was seated at the head of our table. When the dinner was over, Joe DiMaggio got up to leave a bit ahead of everyone else. He walked to the head of our table and paid his respects to my grandfather before leaving.

A couple months later, when grandpa was ill, he said to me, “At least we made it to Yankee Stadium.”

Ray Fisher died in Ann Arbor on November 3, 1982, some three months after his trip to New York. In 2003, at the request of SABR, the state of Vermont erected a historic site marker near his birthplace in Middlebury.

Sources

A version of this biography originally appeared in Green Mountain Boys of Summer: Vermonters in the Major Leagues 1882-1993, edited by Tom Simon (New England Press, 2000).

In researching this article, the author made use of the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, the Tom Shea Collection, the archives at the University of Vermont, and several local newspapers. In addition, the author wishes to thanks John Leidy for his research assistance.

Full Name

Ray Lyle Fisher

Born

October 4, 1887 at Middlebury, VT (USA)

Died

November 3, 1982 at Ann Arbor, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.