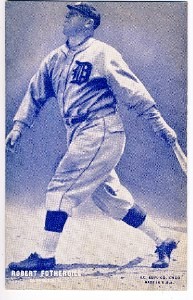

Bob Fothergill

It would be easy to mock someone with a nickname like Fothergill’s, but Fatty Fothergill couldn’t have been too fat. Once after hitting a home run at Fenway Park for the Detroit Tigers, he rounded the bases and did a front flip landing on home plate. At 5-feet-10.5 inches he struggled with his weight and is listed at 230 pounds. Kirby Puckett was 5-foot-8 and weighed 210 but you can bet no one ever called him “Fats.”

It would be easy to mock someone with a nickname like Fothergill’s, but Fatty Fothergill couldn’t have been too fat. Once after hitting a home run at Fenway Park for the Detroit Tigers, he rounded the bases and did a front flip landing on home plate. At 5-feet-10.5 inches he struggled with his weight and is listed at 230 pounds. Kirby Puckett was 5-foot-8 and weighed 210 but you can bet no one ever called him “Fats.”

And Fothergill in some ways had as good a career as Puckett. Both played 12 major-league seasons. Puckett’s lifetime average was .318. Fothergill’s was .325. That mark ranks him in the top 50 hitters of all time. Trying to take the comparison too far would not be too productive, but suffice it to say that Fothergill had a fine major-league career.

He was born Robert Roy Fothergill on August 16, 1897 in Massillon, Ohio. His father was William Fothergill, a fireman in a steel rolling mill in Massillon. His mother was Anna Featheringham, and before she and Fothergill married, Anna had borne a daughter out of wedlock, Ethel, with a man named George Myers. Fothergill adopted Ethel when he married Anna on the Fourth of July, 1896. Ethel was four years older than Bob. The fruit of the Fothergill-Featheringham union also included Bob’s younger sister Mary Matilda, born in 1901. Unfortunately, William Fothergill had died from tetanus five months earlier, after stepping on a rusty nail.

Both of Bob’s parents were natives of Ohio. Anna married Lewis Pritchard and the couple had twin girls, Irene and Arline, born in November 1910. By the time of the 1920 Census, Bob was still living at home in Massillon, and was now listed as the stepson of Pritchard, a carpenter and mill worker. Bob, now 23 years old, was employed as a blacksmith. It was also the first year he played professional baseball. His sister Ethel was a bookkeeper in a furniture company at the time of the 1910 United States Census.

Bob had no more than a grammar school education, reportedly leaving school to try and make a living at football. He played professionally both for Massillon Tigers and for Canton. He played semipro baseball, too, but it was almost certainly with tongue in cheek that he later penned a column “How I Got My Start in Baseball” for the Chicago Tribune, saying, “When I was 16 years old I weighed only 125 pounds, and while I was making some money in semipro games at the time, it did not seem to me that I was getting a balanced diet. I had heard that baseball managers and trainers in the big leagues were particularly eager to see that their players were well fed, and this understanding caused me to decide then and there that I would be a major league player.” [Chicago Tribune, April 30, 1932]

His first regular baseball gig was with the Massillon Agathons, in the Steel League. SABR researcher Craig Lammers reports that Fothergill was first signed professionally by Arthur Hartle, per the Massillon Daily Independent of August 18, 1920. Pants Rowland, former White Sox manager, took some credit as well, at least for promoting him. The January 8, 1942 Sporting News has a column by J. G. Taylor Spink in which Rowland says he was scouting for the Tigers in 1920 and rated his top accomplishment of that year as “bringing up Fat Fothergill.” (His nickname varied from Fat to Fats to Fatty.)

Fothergill was signed by the Detroit Tigers and placed with the Bloomington Bloomers in the Three-I League (Class B) in 1920. He appeared in 136 games for the Bloomers and hit well, .332 with 10 home runs, 21 doubles, and 15 triples. Despite the weight he eventually put on (he said “I was still light” and weighed 160 when playing for Bloomington), he was always remarkably fast. In 1921, Fothergill moved up the ladder to Double A and played for the Rochester Colts in the International League. There he more than kept pace, batting .338 and improving his slugging percentage significantly, from .482 to .538.

Bob married Marie Barth in February 1922, and the Tigers had him start the year with the big-league ballclub. There was the inevitable joking, though, about his weight. Ty Cobb was the Tigers player-manager in 1922, and he supposedly said, “We’d have to enlarge the ball parks in this league if we kept him.” [Hammond Times, March 25, 1938]

Fothergill was 1-for-3 in his April 18 debut, the fifth game of the season, starting in center field and driving in the only Detroit run in a 5-1 loss to the White Sox in Chicago. Three days later, in his first home game, he had his best day of the year, going 3-for-5, with two doubles, and driving in four runs. He stayed with the Tigers through May 23, and though he was still hitting .317, he was sent back to Rochester (the Colts were now the Tribe) where he hit .383 in 101 games. On August 26, Harry Heilmann broke his collarbone in a collision at first base during a game in Washington. He was lost to the Tigers for the season, and the call went out to Rochester for Fothergill. His 397 at-bats were a little short of the requisite number for the batting title but Fothergill’s .383 average far exceeded the .362 managed by the official champion, Reading’s Frank Gilhooley.

Fothergill reached Detroit in time for the August 31 ballgame and he collected 10 hits in his first six games. Over the month of September, he improved on his earlier average, finishing the season hitting .322. He’d driven in 29 runs, but he still hadn’t had a home run. That first homer came in 1923, one of three runs scored against Philadelphia on August 16 when George Dauss shut out the A’s at Navin Field. Fothergill later said he weighed 171 pounds in 1922.

Working much of 1923 as a pinch hitter, he finished at .315 with 49 RBIs. By the end of his career, Fothergill had amassed a then-record 76 pinch hits. [The Sporting News, November 9, 1933] Some won games, of course, such as his bases-loaded drive in the bottom of the 10th inning which beat Washington on June 4, 1924. He missed a fair amount of 1924, first due to a shoulder injury in July. He returned and got in four games before being struck with ptomaine poisoning, which laid him low for six weeks. [The Sporting News, August 21, 1924] That year his average dropped to .301.

Over the next five seasons, Fothergill kept putting on weight and improving his average. He claimed a correlation between the two. “I wish to point out that the year I reached my maximum weight, due to the scientific feeding of which I had dreamed when I entered baseball as a career, I was barely nosed out for the American League batting championship.” [Chicago Tribune, April 30, 1932] When Ty Cobb began to play less, not as easily able to cover as much ground, Bob began to play more. The transition was evident in 1926, with one Feg Murray cartoon and article headlined “He Ousted Cobb.” The article noted, “Robert Roy Fothergill has claim to the double distinction of forcing the famous Ty Cobb into semiretirement, and to being benched for hitting the high average of .353.” [Los Angeles Times, August 27, 1926] The benching referred to a time in mid-1925 when Cobb, Heilmann, and Al Wingo were all hitting close to .400 — and Fothergill was forced to take a seat. In 1926, his .367 mark ranked him third in the league and in 1927, his .359 was fourth best. He ranked fifth that year both in OPS and RBIs. He also hit for the cycle on September 26.

Before 1927, with three future Hall of Famers in the outfield (Cobb, Heilmann, and Heinie Manush) playing time was difficult to come by. Fothergill expressed a desire to be moved to a club where he could get more playing time, but it never became an unpleasant issue. [The Sporting News, December 4, 1924] He couldn’t have enjoyed seeing his corpulence treated so cavalierly in the newspapers; the November 26, 1925 Sporting News even had a front-page headline reading “Some Kind Words for Tiger Fat Boy”. The article said he was the best fly catcher on the Tigers, and had the best arm as well. Sportswriter Sam Greene suggested that “Detroit should capitalize the natural showmanship that belongs to the fat boy of its outfield.”

It was to some extent unfortunate that much of the time, Fothergill played in the shadow of Heilmann. Though Fothergill’s lifetime average during the nine seasons he played for Detroit was .337, Heilmann hit over .390 four times, once batting .403, and won four batting titles. It was only in 1926, when Cobb began to play less, that Bob began to play more. In 1927, with Cobb having moved to Philadelphia, Fothergill got off to a terrific start, hitting safely in every one of his first 18 games and batting over .500 for most of the first few weeks and over .400 late in May. He finished up the year batting .359.

He was a competent defensive outfielder, but was a little too aggressive as a baserunner. He stole 42 bases, but was caught 52 times — and it would have been 53 had his steal of home on June 25, 1927 not resulted in the catcher dropping the ball. His 23 steals in 1922 with Rochester may have given him false confidence. He also simply liked to steal bases. Bill Braucher wrote in the Hammond Times, “When Fothergill took a header into a base, it was an eye-filling spectacle, and he loved to steal because it was one of his life-time ambitions to correct any impression the fans might have that because he was big he was slow. Fothergill was proudest, next to his hitting, of his ability to get around.” [Hammond Times, March 25, 1938] In a column headlined “Fat Players Shine in Majors”, Irwin M. Howe wrote that Tigers fans failed to understand why manager Cobb didn’t use Fothergill more. He was, after all, “about the fastest man on the team.” [Atlanta Constitution, December 22, 1925] Observers at the time did comment on his tendency to run into outfield fences; he was hurt and missed a few games when he crashed into the left-field fence in the August 10, 1927 home game.

His love of stealing brings to mind one of the best Fothergill anecdotes. When umpire George Moriarty took two years off from umpiring to manage the Tigers (1927 and 1928), he advanced the argument to his players that stealing home was as easy as stealing any other base. As a major league player, Moriarty had stolen home a few times. Fothergill piped up, declaring that he would “teach these guys” how to do it. The story has it that he strode to the batter’s box, tripled, and then stole home on the first pitch. [Hammond Times, March 25, 1938]

Moriarty also figures in another Fothergill tale which was supposed to have happened in late July, after Fats had been under unrelenting pressure from his manager to take off weight or face hefty fines. Fothergill was protesting a called strike and took a bite out of the left arm of umpire Bill Guthrie. Moriarty supposedly proclaimed, “A ballplayer who will eat an umpire must be hungry or something,” and suspended the weight-loss program. This would have had to be 1928, and that was the year that Fothergill got off to an uncharacteristically slow start out of spring training in San Antonio. He’d weighed in at 239 pounds, which he’d explained to Moriarty, “I’m fat on my mother’s side.” The manager wanted to get him down to 210. [New York Times, March 24, 1928] Fothergill said the diet hampered his hitting: “Detroit pays me to hit. I can’t hit if I ain’t got the power and I ain’t got the power if I don’t eat. And when I eat what I like I get fat. When I diet, I don’t hit. So what in blazes am I going to do?” He claimed the baseball life was too soft, and the hours weren’t long enough. One of his teammates said, “If you get much fatter, Bob, the fans will begin to think you are an understudy for the Graf Zeppelin.” [Los Angeles Times, January 5, 1930] Newspaper stories described him as a “man mountain” and the like.

“The People’s Choice” — that’s what Fothergill was known as in Detroit. He was a very popular player, perhaps in part because of his girth. Any player who averages .337 over nine years with a team is bound to be popular, but here was a Midwesterner who didn’t put on airs, a ballplayer who had a weight problem and struggled with it — someone with shortcomings that the average person could relate to. He played with flair and enjoyed what he was doing. It’s not surprising he might have had the same sort of appeal that a Rich Garces, known as “El Guapo,” had with the Red Sox and other teams decades later, or even Babe Ruth. He was more agile than either of them, and at least once ended a home run trot with a complete flip in the air, coming down on home plate. Lee Allen wrote of him, “He was one of the last of those rare spirits who appeared to play for the fun of it, and he seemed to be able to extract the fullest amount of pleasure from life. After the game, you could find him with a thick porterhouse steak and a seidel of beer, and he would chuckle to himself, ‘Imagine getting paid for a life like this!’” [“A Study in Suet,” The Complete Armchair Book of Baseball]

Size and shape aside, he truly played exceptionally good baseball. A good first-pitch hitter, he didn’t hit below .300 for any of his first eight years in the majors.

In 1930, John Stone made a splash and won the left-field slot for Detroit. The 32-year-old Fothergill was hitting .259, much lower than usual for him. There were cracks from some of the Detroit fans about him not hitting his weight. The Tigers put him on waivers and he was claimed by the White Sox on July 18. Stone played well for Detroit, but Fothergill hit .296 the rest of the year and .290 over two and a half seasons with Chicago.

Fothergill went to spring training with the White Sox in 1931 and had a largely uneventful season with them, with a .282 average when it was all over. There was one spectacular day worth remembering: July 28 in Yankee Stadium. New York held a 12-3 lead after seven, but Chicago scored 11 times in the top of the eighth inning and won the game, 14-12. Fothergill had doubled twice earlier in the game, and added both a home run and a triple in Chicago’s big inning.

He had started to slow some on defense by this time, though he picked up his average to .295 in 1932. On December 15, 1932 the White Sox took advantage of the slight bump in his production and packaged two outfielders (Fothergill and Bob Seeds) and two infielders (Johnny Hodapp and Greg Mulleavy) to the Red Sox for right-handed pitcher Ed Durham and shortstop Hal Rhyne. Earlier that offseason the White Sox had acquired Al Simmons and Mule Haas for their outfield and Jimmy Dykes as an infielder.

Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey and GM Eddie Collins came on board early in 1933, and manager Marty McManus was prepared to lead the Red Sox into a new era. When the train carrying the Red Sox was in a wreck in Delaware heading north from spring training, Seeds said his first thought when being thrown from his berth at 3:15 AM was that it was Fothergill sliding into home plate. Actually, Fothergill missed out on the wreck; he’d been given leave to return to Massillon where his sister was ill.

He had a good start to the 1933 season at the plate, helping win a couple of early ballgames, but there was the occasional outfield gaffe. His Tigers roommate Billy Rogell told of one time: “Fats was chasing a foul ball and there was a light hill before the fence. He fell down and the ball hit him in the seat of his pants. I went out to retrieve it, but both of us started laughing so hard I couldn’t throw it back to the infield.” [Baseball Digest, December 1993] But it was always his work at the plate that made Fothergill the ballplayer he was, and in 1933 he seemed to rebound. Never once did his average dip below .300, even for a game. He was mostly being used as a pinch-hitter, and also served as first-base coach. Through July 5 he had 32 at-bats in 28 games, but batting .344 was apparently not good enough. The Red Sox had purchased Freddy Muller and Bucky Walters from the Pacific Coast League, and wanted to give the younger players a chance to shine. Fothergill was released on July 7. For the season, Muller hit .188 and Walters .256.

Fothergill next joined the Minneapolis Millers and appeared in 30 games late in 1933, collecting 96 at-bats. His average was exactly the same .344 as it had been in Boston at the time of his departure, but he was released by the Millers at the end of the season. His professional baseball career had come to an end.

Fats continued to play sandlot ball in the Detroit area and took a job in the personnel department of the Ford Motor Company. In June 1937, Bob Fothergill was named baseball and football coach at Detroit-based Lawrence Institute of Technology. There’s one last story that comes from that appointment. He’d ordered a size 50 baseball uniform so he could suit up for the games. The company left the uniform out of their shipment, assuming it was an error that any student playing baseball would be wearing a size 50.

Sadly, in March 1938 Fats Fothergill collapsed due to what obituaries termed a “nervous ailment”, and died several days later, at St. Joseph’s Mercy Hospital in Detroit, on March 20. The proximate cause of death cited on his death certificate was a cerebral hemorrhage. He left his wife Marie, his mother (he wasn’t yet 41 years old), and four sisters. He had no children. He is buried in his old home town of Massillon, Ohio.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the text, and the Fothergill player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the author used the online SABR Encyclopedia, retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Craig Lammers, Rod Nelson, Frank Russo, and Dennis Vanlangen. Maurice Bouchard helped with genealogical information, as did Fothergill’s nephew Floyd Sense and his wife Donna Sense.

Full Name

Robert Roy Fothergill

Born

August 16, 1897 at Massillon, OH (USA)

Died

March 20, 1938 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.