Ernie Orsatti

Few people have the talent and good fortune to have successful careers in two such diverse fields as professional sports and the film industry. Ernie Orsatti was one of those lucky few.

In his nine-year career with the Cardinals (1927-1935), Orsatti hit .300 or better in six seasons, twice hit over .330, and finished with a lifetime average of .306. The Los Angeles native’s colorful wardrobe also lent a touch of Hollywood glamor to the notoriously unkempt Gas House Gang. As successful as it was, Orsatti’s baseball career was really an interlude in a more extensive career in Hollywood. Before he became a professional ballplayer, he was a movie stuntman, prop man and bit player. Then, when his major-league career ended, he and his brothers ran one of the most influential talent agencies in Los Angeles.

Ernest Ralph Orsatti was born in Los Angeles on September 8, 1902. He was the sixth of seven children born to Maurizio and Maria (Manze) Orsatti, Italian immigrants whose names were anglicized to Morris and Mary in the US. Employed as a tailor when the couple were living in Philadelphia, after moving to Los Angeles Morris became the owner of the International Steamship and Railroad Ticket Agency.

Orsatti’s path to professional baseball was anything but typical. In fact, he had no childhood aspirations of playing baseball. Growing up in Los Angeles, he dreamed of a career in the movies and spent his spare time hanging around the studios and doing odd jobs. “My interest, as a boy, was in motion pictures and not in baseball,” he told The Sporting News. “I wanted to be an actor, a director, a cameraman, anything that would identify me with motion pictures. In 1920, I decided to quit school and devote all my time to the picture business.”1 He went to work full-time at the studios, first as a “gofer,” then as a stunt man. He walked on the wings of airplanes, dived off cliffs, and did automobile and boat stunts.

In 1922 Orsatti went to work as a prop man and bit player at the studio of the great silent film comedian Buster Keaton. Though he never doubled as a stuntman for Keaton (who did his own stunts), he did double for the actor in a scene in the 1924 film Sherlock, Jr. At 5-foot-7 and 150 pounds, Orsatti was a good physical match for the 5-foot-6, 140-pound Keaton.

A lifelong baseball fan and a decent player, Keaton had an indoor baseball team and was also part-owner of the Vernon (California) Tigers in the Pacific Coast League. Orsatti played first base and caught for Keaton’s team from 1922 to 1925. When Turkey Mike Donlin, a former major leaguer turned Hollywood supporting actor, saw Orsatti play, he told Keaton that the young man could make more money playing baseball than by working in the studio. In the spring of 1925, Keaton walked onto the movie set where Orsatti was working and handed him a contract to play for Vernon.

After appearing in six games for Vernon, Orsatti was sent to Cedar Rapids (Iowa) in the Class-D Mississippi Valley League, where he hit .347. It was while Orsatti was at Cedar Rapids that Branch Rickey saw him play and made him part of the Cardinals organization by purchasing his contract.2 Orsatti moved up the Cardinals’ minor-league ranks quickly, hitting .386 at Omaha of the Class-A Western League in 1926 and .330 with Houston of the Double-A Texas League in 1927. The 24-year-old, left-handed-hitting outfielder made his major-league debut on September 4, 1927.

Though he showed he could hit major-league pitching (.315 in 92 at-bats), Orsatti was less adept at playing the outfield (five errors in 26 games) and was sent to the Minneapolis Millers of the Double-A American Association in 1928. After hitting .381 with a career-high 15 homers, he was recalled by the Cardinals on August 18.

On August 24 Orsatti’s first-inning home run gave the Cardinals a 1-0 win over the Philadelphia Phillies, keeping the team in first place, where it remained for the rest of the season. In his first six games, Orsatti hit three home runs, the only homers he would hit in 69 times at bat that season. (That brief power surge notwithstanding, in 2,165 career at-bats with the Cardinals, Orsatti hit only 10 home runs.)

In 1929, appearing in more than 100 games for the first time, Orsatti hit .332 while playing all three outfield positions. He did not play in 100 games again until 1932, when he had his best season, hitting .336 (sixth best in the NL) and driving in a career-high 44 runs.

After the 1932 season Orsatti was sent a contract offering the same $4,500 he received in 1932. He met with Branch Rickey, hoping to convince him that his performance merited a raise. No sooner did Orsatti raise the issue than Rickey received a phone call he said was from the general manager of one of the Cardinals’ minor-league clubs. Rickey purportedly said, “You need an outfielder? I’ll call you back in a few minutes. I think I’ll have one available for you.”3

When Orsatti again tried to discuss the contract after Rickey hung up, the phone rang again. This time it was the GM of another farm team asking Rickey for an outfielder. To this request Rickey replied, “I’m sure I’ve got the guy for you.” When Rickey hung up and asked Orsatti what it was he wanted, Orsatti replied, “I just wanted to ask you for a pen, Mr. Rickey, so I can sign my contract.” According to William Veeck, Sr., the Chicago Cubs executive (and father of the more famous Bill Veeck), the phone calls were fake. Rickey could set off the telephone bell by stepping on a foot pedal under his desk.4

After hitting under .300 (.298) for the first time in 1933, Orsatti hit an even .300 in 1934, then slumped to .240 in 1935. Before the 1936 season the Cardinals planned to send him to Rochester, but Orsatti refused and left baseball.

Orsatti’s first four seasons with the Cardinals (1927-1930) came at a time when batting averages were among the highest in history. In fact, three of the top 10 National League averages were recorded in those four years. Still, Orsatti hit well above the league average in every one but the last of his nine seasons. In 1930, when the NL batting average of .303 was the second highest in history, Orsatti beat it by 18 points. And in 1932, his career-high average of .336 was 60 points above the league average.

Orsatti played in four World Series (1928, 1930, 1931, and 1934). In the 1934 win over the Tigers, he appeared in all seven games and hit .318 with a .423 on-base percentage. According to player-manager Frankie Frisch, Detroit fans were so bitter about losing the 1934 Series to St. Louis that when Orsatti was in Detroit on a business trip 25 years later and tried to check into the Sheraton-Cadillac Hotel, where the Cardinals stayed during the ’34 Series, the desk clerk refused to give Orsatti a room. “Ernie had to go over the clerk’s head to get a room at the hotel,” said Frisch.5

For a consistent .300 hitter, Orsatti had a hard time cracking the starting lineup. In only four of his nine seasons did he play in more than 100 games. (An ankle injury limited him to 48 games in 1930.) A 1931 preseason article in The Sporting News speculating on who might start in left field concluded that Orsatti “seems to be the outstanding candidate for the job” since he was “an athlete with plenty of color and a fine competitive spirit. He is fast and able to cover a large outfield, and with a better-than-average throwing arm.”6

However, Orsatti played in only 70 games that season, 32 as a starting outfielder. Chick Hafey replaced him in left field (even though “Orsatti was pounding the ball hard”) because left field was the only position Hafey could play. As for a possible trade, “the little Italian probably would not object to a transfer, if it meant he could play regularly. No ball player hates the bench more than Ernie.”7

Orsatti himself attributed his limited playing time to the abundance of good outfielders in the Cardinals organization. “In one way, I came along at the wrong time,” he said. “The Cardinals were loaded with outfielders. Every year I’d go to camp thinking I finally had a regular job locked up when some phenom would come along. In 1934, I finally thought I had a regular job in right field. But Branch Rickey drafted an American League retread, Jack Rothrock, who had the best year of his career.”8 Rothrock started nearly every game in right field, while Orsatti started 90 in center.

It was during that 1934 season that Orsatti made a brief return as an actor. On June 26, before a game against the Giants, a scene from a murder mystery, Death on the Diamond, was filmed at Sportsman’s Park. In the movie a number of Cardinals players are murdered as part of a plot to keep the team from making it to the World Series. The scene takes place late in the season, when the fictional Cardinals are fighting for the pennant. Orsatti played the role of a player who was shot to death while running the bases.9 A New York Times movie critic wrote that in the film the “hitherto unsuspected hazards of ball playing are described with an entertaining combination of humor and grim melancholy.”10

Having risked his life as a Hollywood stuntman, Orsatti brought that same daredevil mentality to the baseball diamond. Leo Durocher, who joined the Cardinals in 1933, described baseball in that era as “a rough-and-tumble no-holds-barred game played predominantly by farm boys. Generally unschooled, generally unspoiled, generally unsophisticated. Right off the farm or down from the hills.”11

According to Durocher, Orsatti fit right in with the scrappy Gas House Gang. Along with Pepper Martin and Frisch, who were called the “diving seals” because of their penchant for sliding head-first, Orsatti, a speedy baserunner, also liked to slide head-first. “The uniforms were so filthy that we could have thrown them in the corner and they’d have stood up by themselves,” said Durocher. “The bills of our caps were all bent and creased and twisted. We looked horrible, we knew it and we gloried in it.”12

Teammate Jim Mooney noted that Orsatti was also a regular part of the famous pepper game the Cardinals put on to amuse the fans during warmups. “Orsatti was a great little ol’ outfielder,” recalled Mooney. “One time we were playing in Chicago, and someone hit a line drive out into center field, and he went out there and caught it and turned two or three somersaults. He was a great little fellow. Orsatti was a showman.”13

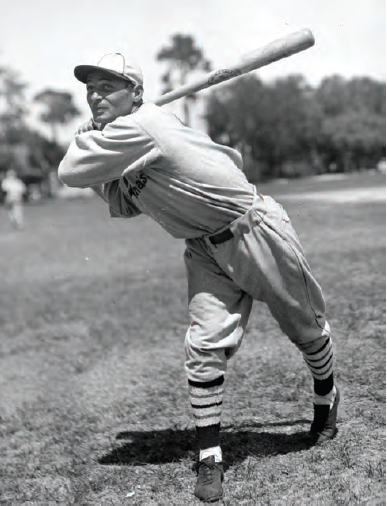

But if Orsatti’s aggressive style and soiled uniform made him a bona fide member of the Gas House Gang on the field, he did not glory in looking horrible off the field. Once the uniform came off and he put on his civilian clothes, he stood apart from his teammates. In addition to his impressively consistent hitting, Orsatti brought a splash of Hollywood style to the happily disheveled Cardinals. A photo above a 1932 Sporting News story shows him wearing fashionable golf knickers and looking for all the world like golf legend Bobby Jones. In the accompanying story, Harry T. Brundidge described Orsatti’s look: “He never wears a hat, and his thick growth of well-oiled black hair is pushed back from his forehead. His flashy sweaters, golf hose, knickers and sports suits are Hollywood importations, and his wardrobe is the envy of most of the younger players.”14 In its obituary of Orsatti The Sporting News wrote that “Ernie’s ensembles made him stand out like a peacock in the ranks of the Gashouse Gang.”15

At a time when ethnic terminology now considered offensive was commonplace, in the same 1932 Sporting News story Brundidge referred to Orsatti as the Dashing Dago, and added that the player, “affectionately known as The Wop in the Cardinals baseball clubhouse, is one of the most popular players on the team.”16

When Orsatti’s major-league career ended in 1935, he returned to Los Angeles and joined his brothers, Frank, Vic, and Al, in the Orsatti Talent Agency.17 According to Orsatti’s son, Ernest F. Orsatti, it was the largest agency in Hollywood.18 Among its clients were such stars as Sonja Henie, Margaret O’Brien, Betty Grable, Judy Garland, and Edward G. Robinson.

In 1939 Orsatti returned to the minor leagues for one season, appearing in 37 games for Hollywood in the Pacific Coast League and in 31 games for Columbus in the American Association. At the time of his signing with the Hollywood Stars, the New York Times reported that Orsatti, “now an actors’ agent, is expected to prove a strong drawing card in the film colony.”19

While still working with his brothers in the talent agency, at some point in the mid-1940s he opened Ernie Orsatti’s Oddity Shop and Florist on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood. His business cards were decorated with a replica of the Cardinals redbirds perched on a bat. According to The Sporting News, at that time Orsatti also held a patent on a candy-vending machine and “collects the royalties on the candy bars found in the lobbies of most theaters throughout southern California.”20

For Orsatti, who spent most of his career in the film industry, the Hollywood lifestyle carried over into his nonprofessional life. In January 1929 he married Martha Von Estey, a San Antonio newspaper writer he met while playing for Houston. In February 1934 Orsatti sued for divorce from Von Estey, charging her with “impairing his baseball efficiency by her ‘constant nagging and quarrelsome nature.’”21

Orsatti wed for a second time in September 1934, marrying opera singer Inez Gorman in Beverly Hills. The couple had two sons, Ernest F. and Frank. While Orsatti’s own career as a stunt performer was short-lived, his two sons continued a tradition that as of 2013 included four generations of Orsattis.

Both sons had long and distinguished careers, each appearing in dozens of films and TV series. In The Poseidon Adventure (1972), Ernie, known as “The Legend,” performed the death-defying stunt of falling from an upside-down table through what had been the ballroom’s ornate glass ceiling. Frank, who died in 2004, worked as Arnold Schwarzenegger’s stunt double in The Terminator and doubled for Burt Reynolds for nine years.22 Young Ernie’s son, Noon, has also appeared in dozens of films and TV series since beginning his career in 1983. Noon’s son, Rowbie, and his daughter, Allie, continue to maintain the Orsatti legacy as stunt performers.

Orsatti’s marriage to Gorman ended in 1952. His son, Ernie, who was 12 years old when his parents divorced, described his father as a great athlete and a talented chef. “One of the biggest parties was held on Christmas Eve,” he recalled, “when he cooked for dozens of people from show business and the opera world.”23

In 1960 Orsatti married Canadian native Alice Joyce Ritchie. He and Ritchie operated Orsatti Bail Bonds in Van Nuys, California, until his death at the age of 65 of a heart attack on September 4, 1968. He is buried in San Fernando Mission Cemetery, Mission Hills, California.

This biography was originally published in “The 1934 St. Louis Cardinals The World Champion Gas House Gang” (SABR, 2014), edited by Charles F. Faber. It also appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, and consulting Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org, the author also conducted a telephone interview with Scott Orsatti on May 31, 2013.

Notes

1 The Sporting News, February 4, 1932: 5.

2 Ibid.

3 Toledo Blade, April 1, 1972: 16.

4 Ibid.

5 Frank Frisch, as told to J. Roy Stockton, Frisch: The Fordham Flash (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1962), 177.

6 The Sporting News, April 9, 1931: 1.

7 The Sporting News, November 5, 1931: 1.

8 The Sporting News, September 21, 1968: x.

9 John Snyder, Cardinals Journal: Year by Year & Day by Day with the St. Louis Cardinals Since 1882 (Cincinnati: Clerisy Press, 2010), 264.

10 New York Times, September 24, 1934.

11 Leo Durocher and Ed Linn, “That Old Gang Of Mine,” Sports Illustrated, April 7, 1975: 84.

12 Ibid.

13 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the Cardinals and Browns (New York: Avon Books, 2000), 186.

14 The Sporting News, February 4, 1932: 5.

15 The Sporting News, September 21, 1968: 36.

16 The Sporting News, February 4, 1932: 5.

17 Vic, who starred in football and baseball in high school, was honored as the best all-around athlete in Los Angeles in 1923 and went on to play quarterback at the University of Southern California. As the prize for winning a home run-hitting contest while in high school, he received the bat used by Babe Ruth to hit the first homer in Yankee Stadium, on April 18, 1923. Ruth had donated the bat to the Los Angeles Evening Herald.

18 Ernest F. Orsatti, telephone interview, March 7, 2013.

19 New York Times, March 29, 1939.

20 The Sporting News, February 5, 1947: 7.

21 San Antonio Light, February 8, 1934: 17.

22 Frank, who aspired to follow in his father’s footsteps as a ballplayer, appeared in 12 games with the Cardinals’ affiliate Brunswick in the Georgia-Florida League in 1963, but his career was cut short by an

23 Ernest F. Orsatti, telephone interview, March 7, 2013.

Full Name

Ernest Ralph Orsatti

Born

September 8, 1902 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

Died

September 4, 1968 at Canoga Park, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.