Charlie Schmutz

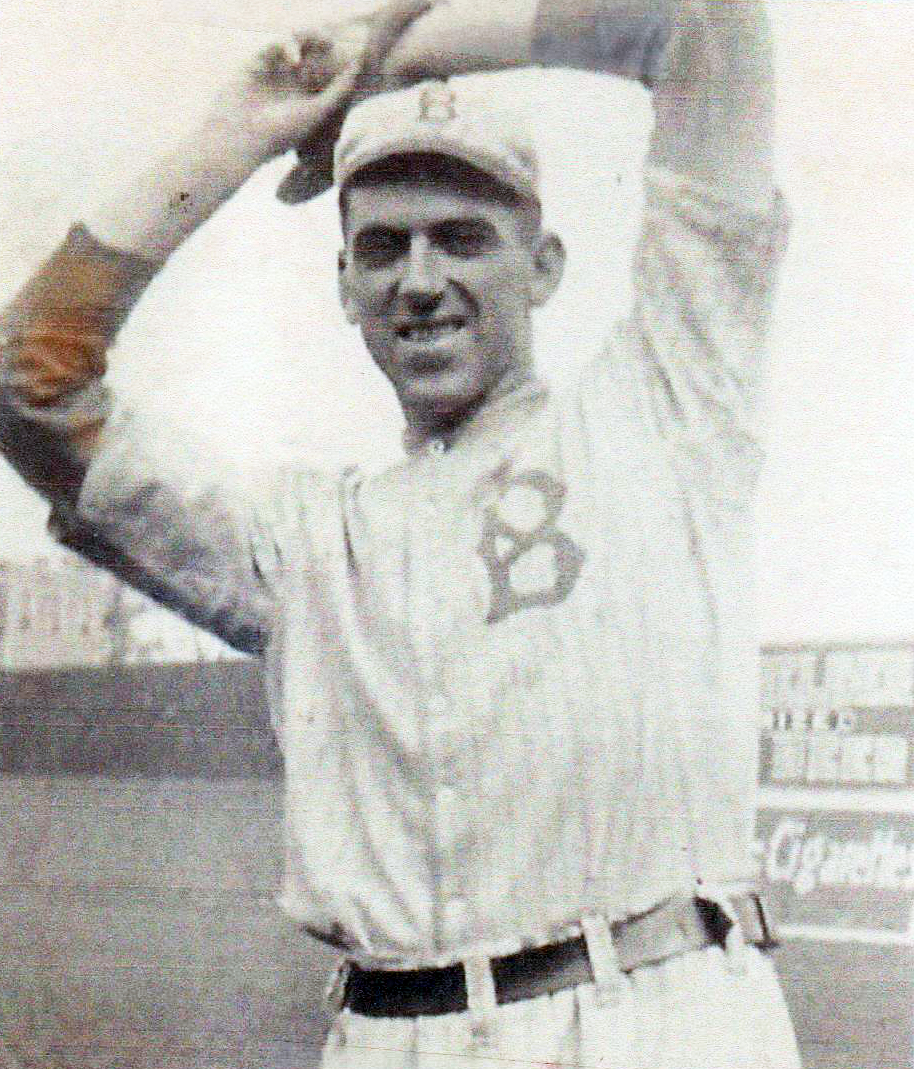

A temperate Pacific Coast climate and rich baseball tradition have made San Diego a longtime spawning ground for major-league talent. As of 2019, the city has sent some 115 of her sons to the bigs. The second, and by far the greatest, of these San Diegans was Ted Williams, whose march to Cooperstown began with the 1939 Boston Red Sox. But some 25 years before The Splendid Splinter made his Sox debut, the trail to the majors for the San Diego-born ballplayer was blazed by a player as obscure as Williams is famous: Charlie Schmutz, a Deadball Era right-handed pitcher. Schmutz’s tenure with the 1914-1915 National League Brooklyn Robins was brief (19 games), undistinguished (one victory), and quickly forgotten. In fact, during his lifetime Schmutz was mostly known only to the baseball fans of Seattle, the place where he grew up and the area where he played the majority of his non-major-league baseball. Nevertheless, Charlie Schmutz is the correct answer to the baseball trivia question: Who was the first San Diego-born major-league player?1

A temperate Pacific Coast climate and rich baseball tradition have made San Diego a longtime spawning ground for major-league talent. As of 2019, the city has sent some 115 of her sons to the bigs. The second, and by far the greatest, of these San Diegans was Ted Williams, whose march to Cooperstown began with the 1939 Boston Red Sox. But some 25 years before The Splendid Splinter made his Sox debut, the trail to the majors for the San Diego-born ballplayer was blazed by a player as obscure as Williams is famous: Charlie Schmutz, a Deadball Era right-handed pitcher. Schmutz’s tenure with the 1914-1915 National League Brooklyn Robins was brief (19 games), undistinguished (one victory), and quickly forgotten. In fact, during his lifetime Schmutz was mostly known only to the baseball fans of Seattle, the place where he grew up and the area where he played the majority of his non-major-league baseball. Nevertheless, Charlie Schmutz is the correct answer to the baseball trivia question: Who was the first San Diego-born major-league player?1

Charles Otto Schmutz was a New Year’s Day baby, born on January 1, 1891. He was the oldest of three children born to streetcar conductor Frank J. Schmutz (1865-1948), and his teenage wife, Alice (née Murphy, 1876-1958).2 While Charlie was still in grade school, the family relocated to Seattle, the burgeoning Pacific Northwest seaport located some 1,250 miles north of San Diego. And it was there that Schmutz first attracted public notice.

Like other marginal major leaguers, Schmutz would later be remembered not for his abbreviated time in big-league livery, but for his schoolboy exploits. Indeed, the playing campaign of Schmutz and his teammates on the 1907 Seattle High School nine was celebrated locally for the succeeding 50 years. By any definition, that Seattle High lineup was loaded with talent. Within a few years, star first baseman Charlie Mullen would begin a five-season major-league career. Three other team members, pitcher Jimmy “Toots” Agnew, third baseman Harry Martin, and memorably named left fielder Ten Million,3 went on to play minor-league ball, while catcher Mert Hemenway, shortstop Ernie Maguire, and outfielders Bill “Wee” Coyle and Fred Hickenbottom would become varsity lettermen at the University of Washington. In the beginning, 16-year-old freshman Charlie Schmutz auditioned for a spot in the overstocked SHS outfield,4 but he was slow-footed and a weak righty batsman. Imposing size – lanky but eventually near 6-feet-2/195 pounds5 – and a strong throwing arm then induced him to give pitching a try. Although it would sometimes later be reported that Schmutz had a sizzling fastball, he initially threw “as slow as molasses in January.”6 But he made good use of a puzzling shot-put pitching motion and had somehow learned to throw a wicked spitball.

On April 17, 1907, Seattle High’s novice pitcher made a truly astonishing debut. Matched in a preseason exhibition game against the professional Seattle Siwashes, a Class B Northwestern League club owned and managed by former major-league catcher Dan Dugdale, Schmutz shut them down on two hits, winning 2-1. The local sports press was dumbfounded, but impressed. “A long-legged lad named Schmutz, who had not been considered good enough for the high school team, pitched a great game and with the aid of a balk motion had the professionals buffaloed,” reported the Seattle Times.7 Meanwhile, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer informed readers that “Mr. Schmutz, a pitcher of the bean-pole variety … was the stumbling block that Seattle could not overcome. From the dizzy heights he handed them down so nicely shaded that only two hits were chalked against him.”8

Overmatched area high-school rivals rarely provided much competition, but when the scholastic season was completed, the Seattle High School team embarked upon something far more ambitious: a transcontinental baseball tour. Such an excursion by a high-school team was unprecedented, and the Seattle Board of Education was unenthused about sending teenage students on a two-month-long cross-country trip. But once a consortium of city businessmen agreed to finance the tour – seen as a useful vehicle for advertising the upcoming 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exhibition9 – the Board acquiesced, deputizing SHS faculty member B.C. Hastings to chaperone the 11-player (plus a student manager) trip.

Arriving in Minnesota on June 17, the boys began a two-month campaign that saw them dominate high-school opposition and hold their own against older, more seasoned semipro clubs. With Schmutz and Jimmy Agnew doing all of the pitching, the SHS squad posted a respectable 16-15 record overall. More than 1,000 locals were waiting to greet them at the train station when they arrived back home. The boys were the toast of Seattle and the recipients of an officially hosted parade through city streets.10

Schmutz, Mullen, Agnew, and most of the other tour players returned to the Seattle High lineup in 1908, but they were no longer the wunderkinder of schoolboy athletics and achieved only mixed results.11 During the ensuing summer, Schmutz, Mullen, and company played for their own self-organized amateur team, the Nationals. Then in the autumn, Schmutz and Agnew pitched semipro ball, mostly for a local nine called the Websters.12 For the 1909 season, Schmutz transferred to newly opened Abraham Lincoln High School. He ended the season by pitching Lincoln to a 4-0 victory over Broadway (formerly Seattle) High13 and “old pal” Jimmy Agnew, thereby capturing the high-school championship of the Northwest for his new school.14

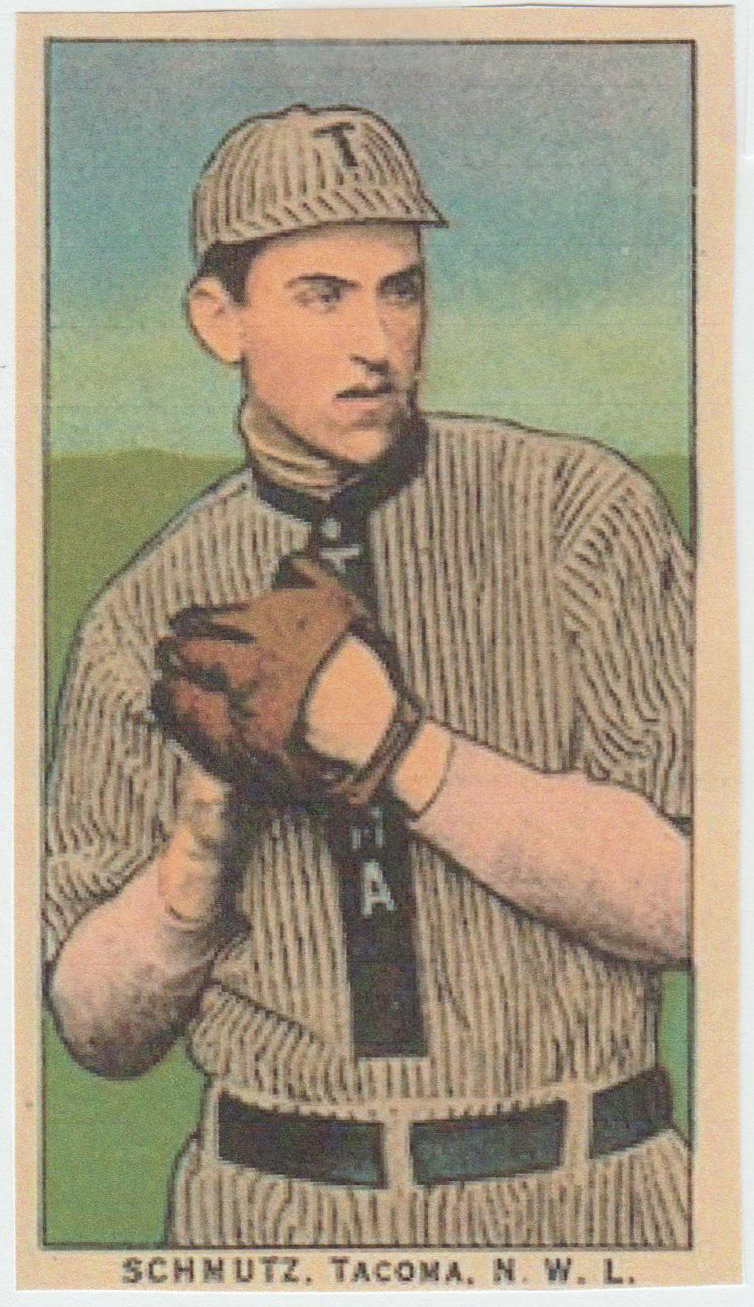

Schmutz left Lincoln at the completion of his junior year and never earned a high-school diploma.15 After working at a neighborhood grocery store, the 19-year-old entered the professional ranks, signing with Tacoma in 1910. After recovering from an early-season bout of blood poisoning, Schmutz became a Tacoma staff mainstay. In 39 games, he posted a 14-20 (.412) record for the 73-84 (.465) Tigers, striking out 120 while walking 81 in 299⅔ innings pitched.16 Charlie returned to Tacoma the following season, going 14-14 in 33 games for an 81-84 Tacoma club.17 He attracted major-league attention in the process. That August it was reported that Schmutz was one of three Northwestern League hurlers signed by retired star Bill Lange for the Cincinnati Reds.18 Schmutz continued pitching for Tacoma throughout the summer, but his transfer to Cincinnati at season’s end seemed confirmed by wide reports that Tacoma club owner George Shreeder had obtained $2,500 from Cincinnati for the rights to Schmutz.19

As it turned out, Shreeder decided that the Cincinnati offer was inadequate for a talent like Schmutz and held on to him for the 1912 season. Charlie then expressed his displeasure at this turn of events by returning his 1912 Tacoma contract unsigned.20 He wanted out of Tacoma. But soon thereafter, the reality of the reserve clause, and perhaps the sale of the Tigers franchise to new owner Edd N. Watkins, compelled him to return.21 The reunion would prove disagreeable, as the latest edition of the Tacoma Tigers was dominated by untalented, often dissipated players who seemed to take pleasure in undermining the work of their staff ace. By mid-July, Tacoma was firmly entrenched in the NWL cellar, while Schmutz’s individual record stood at a shuddering 2-14. Still, he remained held in high regard by NWL observers. A nationally circulated United Press wire report declared: “Schmutz is considered one of the best pitchers in the league, but despite his excellent work he has won two and lost 14 this season through the poor support given him. He was not liked by the loafing members of the team and they practically threw his games away. (Schmutz) is a clean living, hard working pitcher.”22 By then, club owner Watkins had seen enough, releasing underperforming malcontents Ody Abbott and Pete Morse, and trading Schmutz to NWL rival Vancouver Bees for three players (who included Jimmy Agnew). In announcing the moves, Watkins hastened to add: “I do not want the impression to get out that Schmutz was traded because he was breaking training rules. He is a man of the best habits and takes the greatest care of himself. While he is a great pitcher, he has not been winning for us and I believe that he will have a better chance to better himself with (Vancouver manager Bob) Brown.”23

As it turned out, Shreeder decided that the Cincinnati offer was inadequate for a talent like Schmutz and held on to him for the 1912 season. Charlie then expressed his displeasure at this turn of events by returning his 1912 Tacoma contract unsigned.20 He wanted out of Tacoma. But soon thereafter, the reality of the reserve clause, and perhaps the sale of the Tigers franchise to new owner Edd N. Watkins, compelled him to return.21 The reunion would prove disagreeable, as the latest edition of the Tacoma Tigers was dominated by untalented, often dissipated players who seemed to take pleasure in undermining the work of their staff ace. By mid-July, Tacoma was firmly entrenched in the NWL cellar, while Schmutz’s individual record stood at a shuddering 2-14. Still, he remained held in high regard by NWL observers. A nationally circulated United Press wire report declared: “Schmutz is considered one of the best pitchers in the league, but despite his excellent work he has won two and lost 14 this season through the poor support given him. He was not liked by the loafing members of the team and they practically threw his games away. (Schmutz) is a clean living, hard working pitcher.”22 By then, club owner Watkins had seen enough, releasing underperforming malcontents Ody Abbott and Pete Morse, and trading Schmutz to NWL rival Vancouver Bees for three players (who included Jimmy Agnew). In announcing the moves, Watkins hastened to add: “I do not want the impression to get out that Schmutz was traded because he was breaking training rules. He is a man of the best habits and takes the greatest care of himself. While he is a great pitcher, he has not been winning for us and I believe that he will have a better chance to better himself with (Vancouver manager Bob) Brown.”23

Truer words were rarely spoken. Once in a Vancouver uniform, Schmutz went on a winning tear, capturing his first nine decisions for the Bees. Charlie finished the season with a combined 13-17 record,24 and reestablished himself as a major-league prospect. He was chosen by the Philadelphia Phillies in the late-season minor-league player draft, and directed to report to the club’s training camp the following spring.25

Once again, Schmutz’s hopes for a major-league chance were dashed, as he appears to have been given no shot to make the roster by the Phillies. Instead, he was returned to Vancouver, where he promptly resumed the excellent work of the previous campaign. By now an improved, more fluid delivery had added some velocity to his fastball. But Charlie still did not throw hard. Instead, he pitched to contact, relying on control and his spitball to get him out of tight spots.26 For the 1913 season, that formula produced a 16-10 record for the NWL pennant-winning Vancouver Bees; his selection to various NWL all-star teams, and, at long last, a legitimate shot at a major-league berth. That July, Schmutz’s contract was purchased by the National League Brooklyn Superbas, reportedly on the recommendation of retired fireballer Amos Rusie.27 The $5,400 that Brooklyn club boss Charles Ebbets paid for Schmutz was high for an untested minor leaguer, but only a fraction of the $60,000 that Ebbets was prepared to lay out for new playing talent that summer.28 New recruit Schmutz was directed to finish the NWL campaign with Vancouver, and then report to Brooklyn manager Bill Dahlen in September.29 For reasons unclear, however, Schmutz remained in the Pacific Northwest that fall.

Prior to leaving his Seattle home for spring camp in February 1914, a grateful Schmutz sent Ebbets a heartfelt letter. “I take the opportunity to state that the ambition of my life – the entering of the major leagues – has been realized,” wrote Charlie, “and I hope that I will be of as much service to you as I have been to (Vancouver manager) Brown. I have taken the best of care of myself this winter and am anxiously awaiting the opening of the training season.”30 Although Ebbets – feeling the competitive pressure applied by the newly arrived Brooklyn Tip-Tops of the upstart Federal League – had overstocked new manager Wilbert Robinson’s pool of pitching candidates, Schmutz showed enough in spring exhibition-game play to survive the cut and make the Opening Day roster.

Once the regular season began, Schmutz saw no action for almost a month. He finally made his major-league debut on May 13, 1914, pitching a flawless inning, with two strikeouts, in relief in a 6-0 loss to Chicago. Two scoreless mop-up relief efforts followed. After three weeks of idleness, Schmutz was back in action again, throwing two innings of shutout relief in a 6-0 defeat by St. Louis on June 13. Five days later, he got the call early, relieving starter Frank Allen in the top of the second inning with the Robins31 already trailing Cincinnati 2-0. From there, Schmutz pitched hitless ball until finally weakening in the ninth, when he gave up two runs on four hits to complete a 4-1 loss to the Reds.

After several more weeks of inaction, Schmutz was finally given a start – in an exhibition game against the Rochester Hustlers of the Double-A International League. He responded to the audition with a complete game four-hit shutout, prompting the press back home to observe that “maybe after that showing fat Wilbert Robinson will give the Seattle lad a chance to work in a real league game.”32 But instead, Brooklyn brass assayed shipping Schmutz to its own IL farm club in Newark “in order that the tall lad from the Northwest will get the player preparation required for big leagues usefulness.”33 Armed with a guaranteed two-season contract – a benefit of Brooklyn’s combat with the Federal League – Schmutz successfully resisted the effort to send him down and remained a member of the big club. Then on July 23, he got his first major-league start in an away game against the St. Louis Cardinals. Schmutz surrendered a run in the bottom of the first, but thereafter held the opposition scoreless until removed in the top of the seventh for pinch-hitter Jack Dalton. A two-out single by Dalton delivered Casey Stengel (Charlie’s road roommate) from third and gave Brooklyn a 2-1 lead. Unhappily for Schmutz, the Cardinals immediately pounced on reliever Ed Reulbach for three runs, leaving the first-time starter with a no-decision in the 4-2 loss.

Three subsequent starting assignments did not go as well. On August 6 Schmutz was yanked after a five-run first inning against St. Louis in a 7-2 loss. Some two weeks later, he left after five innings trailing 4-0 in a 7-3 defeat by St. Louis. On September 7 he retired only one batter, giving up three runs in a 7-6 loss to Philadelphia. A final start on September 11 produced a better effort, an 11-hit complete game in a 3-0 loss to aging New York Giants pitching master Christy Mathewson. The defeat, however, dropped Schmutz’s record to 0-3. But with the 1914 season approaching an end, Charlie finally registered a victory. Relieving starter Reulbach with the Robins trailing 2-0 in a September 25 home game against Pittsburgh, Schmutz was the beneficiary of shoddy late-inning Pirates fielding and emerged a 3-2 victor. Ordinarily a harmless batsman, Charlie doubled in the ninth and scored the winning run himself on a throwing miscue by Pirates shortstop Wally Gerber. Days later, Schmutz concluded his maiden major-league season with a substandard (five innings/four runs) no-decision relief outing in a 9-7 loss to the Philadelphia Phillies.

In all, Charlie Schmutz made 18 appearances for Brooklyn, posting a 1-3 record with a 3.30 ERA in 57⅓ innings pitched. He struck out 21 enemy hitters and walked 13, while yielding a .265 batting average to opposing hitters. Despite such mediocre numbers, Schmutz had made a decent enough rookie showing, and the youngster could be expected to improve under the tutelage of manager Robinson, an astute developer of pitching prospects. But Schmutz would have to, as the Robins had made considerable strides (a 10-win improvement over the previous year) in team performance. Competition for spots on the 1915 club was likely to be brisk.

Despite unconfirmed reports of offseason physical (shin splints)34 and health (malaria)35 problems, Schmutz reported to Brooklyn spring camp in his customary excellent condition. Once again, candidates for the pitching staff were plentiful, but Schmutz’s cause was aided by arm miseries that put veteran hurlers Nap Rucker and Jack Coombs temporarily on the shelf. Soon the preseason work of Schmutz and other youngsters drew the praise of manager Robinson. Following an exhibition game against the Washington Senators, Robbie declared, “In Schmutz, [Ed] Appleton, [Sherry] Smith, and [Wheezer] Dell, I have a quartet of young pitchers who will win a lot of games for me this summer.”36

Schmutz was among the pitchers who made the expanded Opening Day roster, and was immediately sent into action in the inaugural game of the 1915 season, against the Giants. Entering the contest with Brooklyn already trailing 7-0, Charlie held Giants bats in check for three innings, but was then tattooed for four doubles and a single in a five-run sixth inning. Schmutz was relieved by Elmer Brown in the seventh – and would never appear in another major-league game. Several days thereafter, he was one of four pitchers sent to the minors as Brooklyn trimmed its roster to the 21-player limit.37

The remainder of the season was mostly grim for Schmutz. He was ineffective pitching for the International League Newark Indians, going 2-4, with a 6.79 ERA in 73 innings pitched. He was remanded back to Brooklyn,38 which immediately optioned Schmutz to the Salt Lake City Bees of the Double-A Pacific Coast League.39 He fared no better there. In eight games, he posted a 1-2 record, with a 5.22 ERA in 29⅓ frames. As September approached and with Brooklyn’s acquiescence, Salt Lake released Schmutz.40 Charlie was then signed by the hometown Seattle Giants of the Northwestern League, where he seemed to regain form pitching against Class B minor-league batters.41 On September 16, a four-hit, 9-1 Schmutz victory over the Spokane Indians gave Seattle the NWL crown,42 and ended a trying year on an upbeat note.

During the offseason, Schmutz filed a grievance with the National Commission, the governing body of Organized Baseball, claiming that he had been underpaid for the 1915 season. Upon consideration, the commission agreed and awarded Schmutz $875, the difference between the salary specified in his binding two-year contract with Brooklyn and what he had been paid while pitching for Salt Lake and Seattle.43 Charlie then returned to the Seattle Giants and registered the most successful year of his professional career. He began the 1916 season by tossing 31 consecutive scoreless innings before a Seattle fielding miscue let in a run.44 By season’s end, Schmutz had posted a 19-11 (.633) record for a weak-hitting, next-to-last-place team that otherwise went 41-61 (.402). His 275 innings pitched demonstrated the soundness of Schmutz’s throwing arm, while his 106 strikeouts were a personal best.45 Yet despite this sterling performance and Schmutz’s youth (he was still only 25 years old), he went unclaimed in the postseason minor-league player draft, unwanted by either a major- or higher minor-league club.

The rejection appears to have soured Schmutz on professional baseball. He refused to report to Seattle’s spring camp the following April, prompting the club to sell him to Vancouver.46 Schmutz would not report there, either. Instead, he signed as pitcher-manager of the Dry Docks, the club entered in the semipro Seattle Shipbuilders League by the Seattle Construction and Dry Dock Company.”47 When not in his baseball uniform, Charlie also held an electrician’s job with the company.48

That winter, with the country by now fully engaged in World War I, Charlie enlisted in the US Army. Initially stationed near home at Camp Lewis, he was soon playing ball for the juggernaut camp baseball team, coached by his friend and former Seattle High School teammate Charlie Mullen. In addition to Mullen and Schmutz, the Camp Lewis squad included former major-league hurlers Jim Scott and Duster Mails, while center field was patrolled by erstwhile Seattle High standout and St. Louis Cardinals farmhand Ten Million.49 The Camp Lewis games came to an end, however, when the outfit was shipped to France that July.

A proud member of the 316 Sanitary Train of the 91st Infantry Division, Sergeant Charles Schmutz alternated duties on the battlefront with playing company baseball during lull periods in the fighting. Although the war-ending armistice was signed in November 1918, his unit remained in France and did not leave for home until April 1919.50 Shortly after his arrival back in Seattle, he married Brenda Jenkins, the daughter of a Seattle shipbuilding magnate. Following a three-week honeymoon in the Canadian Rockies, the newlyweds set up housekeeping in a posh Seattle neighborhood, their new-built residence courtesy of the bride’s wealthy father. In February 1920 the couple had their first child, a daughter named Nancy Low who, sadly, died shortly after birth. Some six years later, the arrival of daughter Nancy Brenda made the Schmutz family complete.

In early 1920, Schmutz had joined the sales force at Graybar Electric, a Seattle wholesaler of electrical supplies and appliances. He would hold well-paying sales and executive positions at Graybar for the next 37 years. While Charlie worked and pitched on weekends for area semipro teams that often rejoined him to his high-school teammates,51 Brenda Schmutz took to the Seattle social circuit. Her attendance, usually in the company of her twin sister, Thelma Jenkins Anderson, and/or her socialite mother, Edith, at high-tone luncheons, art gallery exhibitions, and the like was regularly noted in the local press.52 The onset of the Great Depression appears to have had no effect of the Schmutzes. Charlie remained gainfully employed, while Brenda (usually with sister Thelma in tow) embarked on lengthy sojourns to Mexico, France, the Orient, and other faraway destinations,53 leaving the care of daughter Nancy to Charlie and the household domestic staff. An unspecified illness, however, brought Brenda’s gallivanting to a premature halt. At age 39, she died at home on July 3, 1938.

In 1940 Charlie remarried, taking 34-year-old divorcee Dorene Young Dusky as his second wife.54 The marriage, alas, was not a happy one, and the couple divorced five years later.55 Now well into middle age, Schmutz, when not attending to work at Graybar Electric, immersed himself in baseball-related activities. He got deeply involved in Seattle youth baseball; played in area old-timers games; was appointed to the Seattle Rainiers Baseball Boosters Association,56 and was a participant in regular reunions of the still locally celebrated Seattle High School team of 1907. In addition, Charlie was an active member of the American Legion and other Seattle civic organizations, and a renowned fisherman.

No one in Seattle was happier than Charlie Schmutz when the Brooklyn Dodgers won the 1955 World Series.57 And four years later, he made the trip to Los Angeles to see his former club capture the 1959 world championship. By now, however, the infirmities of advancing age were closing in on Schmutz. He survived colon cancer surgery but was plagued by heart disease. On June 27, 1962, he suffered a heart attack while at home and was pronounced dead on arrival at Seattle’s Providence Hospital.58 Charles Otto Schmutz was 71, and was survived by his brother, Ernest, sister, Frances Schmutz Nelson, daughter, Nancy Schmutz Hall, and four grandchildren.59 After services at a local funeral parlor, his remains were cremated and subsequently inurned at the Washelli Columbarium at Evergreen-Washelli Memorial Park, Seattle60 – a far remove from San Diego, the sunny Southern California city where the full and eventful life of Charlie Schmutz had begun some seven-plus decades earlier.

Acknowledgments

This biography is adapted from an article published in The National Pastime, Summer 2019. It was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

Sources for the biographical info posited above include the Charlie Schmutz file with player questionnaire maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; US Census data and Schmutz family posts accessed via Ancestry.com, and certain of the newspaper/internet articles cited below. Unless otherwise noted, minor-league stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference, major-league data from Retrosheet.

Notes

1 Debuting with the Boston Red Sox in 1908, Deadball slugger Gavvy Cravath preceded Schmutz to the majors. But Cravath was born in San Diego County, not the city itself. Cravath’s birthplace in Poway lies about 22 miles northeast of the San Diego city line.

2 Charlie’s paternal grandparents were Swiss immigrants who settled in Wisconsin. His siblings were brother Ernest (born 1894) and kid sister Frances (1911).

3 Ten (No Middle Name) Million later became a St. Louis Cardinals farmhand and seemed a highly-promising prospect until a knee injury ruined his playing career.

4 Evidently unsure of his chances of making the Seattle High team, Schmutz also organized a sandlot club called the Nationals to play other Puget Sound amateur nines. See the Seattle Times, March 21, 1907. And even after he became the high school’s star hurler, Schmutz pitched for the Nationals, as well.

5 Current baseball authority list Schmutz’s height as 6-feet-1½. Some Deadball Era sources had him a bit taller, and the posthumous player questionnaire completed by his brother Ernest gave Charlie’s height as 6-feet-3.

6 As subsequently observed in “Schmutz Wins for Seattle,” Seattle Times, September 5, 1915.

7 See “Dug’s Team Stung by High School Bunch,” Seattle Times, April 18, 1907.

8 See “High School Beats Seattle; Schmutz Is Wizard,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 18, 1907.

9 The exhibition was Seattle’s first World’s Fair-type extravaganza, intended to advertise economic opportunity in the city and to promote Seattle as the gateway to Alaskan adventure and riches. The Seattle High School baseball tour eventually cost its sponsors almost $4,000.

10 For a detailed retrospective on the Seattle High tour of 1907, see David Eskenazi, “Wayback Machine: Seattle’s First Ambassadors,” posted at sportspressnw.com, October 18, 2011. See also, Clark Squire, “Sizzling Schmutz,” Seattle Times, April 23, 1956.

11 Since its opening in 1902, the school’s official but seldom-used name was Washington High School. For some reason, local newspapers sometimes referred to Seattle High by its official name (Washington HS) during the 1908 baseball season. See e.g., “Washington High Team Gets Whitewashed,” Seattle Times, April 8, 1908.

12 See e.g., Seattle Times, September 28, 1908: “Schmutz had his spitball well tuned and struck out 15” during a 13-inning 1-0 Websters victory over the Clinton All-Stars. At the time, there was nothing deemed remarkable about high schoolers like Schmutz playing semipro ball, and doing so did not jeopardize their high-school eligibility. A photo of Schmutz, Jimmy Agnew, and a Tacoma High School catcher named Hanna in their Websters uniform was published in the Seattle Times, July 19, 1908.

13 Because Seattle (Washington) High School was no longer the city’s only public high school, the Board of Education decided to rename the institution Broadway High School. The new name took effect in fall 1908, and was taken from the location of the erstwhile Seattle High School at Broadway and East Pine Street. For more on the confusing early-century name changes of Seattle’s high schools, see “Seattle Public Schools, 1862-2000: Broadway High School,” historylink.org, posted September 4, 2013.

14 As per “Lincoln Wins Championship,” Seattle Times, June 5, 1909.

15 The Baseball-Reference entry for Charlie Schmutz (and high-school teammate Charlie Mullen, as well) currently lists him as having attended Seattle’s Broadway High School. This is incorrect, as Schmutz was never a student at the institution during the years (1909-1946) that it was called Broadway High. In his freshman and sophomore years (1906-1908), Schmutz attended Seattle High School, while he spent his junior year (1908-1909) at Lincoln High. Similarly, Mullen never attended Broadway HS. He was a June 1908 graduate of Seattle High School.

16 Schmutz’s strikeout total is taken from the 1911 Reach Official Guide, 374. His other stats come from Baseball-Reference.

17 It was subsequently reported that the 1911 season log of Schmutz and other Tacoma hurlers was brought down by the club’s second-half disintegration. See the Tacoma Ledger, January 9, 1912.

18 See “Miles Netzel Signs with Reds,” Seattle Times, August 4, 1911.

19 See “Three Beauties for $7,500,” Detroit Times, October 6, 1911. The other Tacoma hurlers reportedly sold to Cincinnati were Fred Annis and Blaine Gordon. The three-pitcher sale was subsequently reiterated in news articles published in the Sault Ste. Marie (Michigan) Evening News, October 11, 1911, Saginaw (Michigan) News, October 13, 1911, (Springfield) Illinois State Journal, October 31, 1911, and elsewhere.

20 As reported in the Seattle Times, January 18, 1912.

21 See “Charley Schmutz Is Ready to Join Club,” Tacoma Ledger, January 29, 1912.

22 Published in the (Portland) Oregon Journal, July 19, 1912, and elsewhere.

23 “Watkins Gives Team General Shaking Up,” Tacoma Ledger, July 19, 1912. Agnew, meanwhile, was wont to take his old high-school teammate’s place on the Tacoma roster and refused to report. Tacoma eventually sold Agnew to the NWL Portland Colts, where he finished the season with a combined 14-12 record.

24 As per final 1912 Northwestern League season stats published in the Oregon Journal, November 12, 1912. NWL stats published in Sporting Life, November 2, 1912, put the Schmutz record at 12-15, but include fewer games (28 v. 33) and fewer innings pitched (254 v. 261) than the Oregon Journal figures. Baseball-Reference has no 1912 numbers whatever for Schmutz.

25 Per the Oregon Journal, September 29, 1912. A rival newspaper had earlier reported that Vancouver had sold Schmutz’s contract to the Phillies in August. See The (Portland) Oregonian, August 6, 1912.

26 A Cincinnati Reds scout named O’Hara discounted Schmutz as a major-league prospect, saying he “has no fast ball. Charlie’s main reliance is his spitball, slow ball, and excellent control.” See “Cincinnati Scout Picked Bob Ingersoll over Schmutz,” Seattle Times, July 9, 1913.

27 As per the New York Tribune, November 2, 1913, and Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, February 1, 1914. At the time, the down-on-his-luck Rusie was on the Tacoma Tigers groundskeeping crew.

28 Per “Dodgers to Pay Out $60,000 for Players,” Washington Evening Star, August 12, 1913, and “These Youngsters Go to Major Leagues Next Season,” Oregon Journal, September 21, 1913. An earlier report that Schmutz had been sold to the Detroit Tigers proved false.

29 As reported in the Kalamazoo (Michigan) Gazette, Philadelphia Inquirer, and Washington Evening Star, July 22, 1913.

30 As reprinted in the New York Tribune, February 1, 1914.

31 The Robins was the new and unofficial nickname bestowed upon the Brooklyn club in 1914 in tribute to popular new manager Wilbert Robinson.

32 See “Schmutz Wins Shut-Out Game,” Seattle Times, July 8, 1914.

33 Per Abe Yager, “The Superbas Revival,” Sporting Life, July 11, 1914.

34 Unidentified 1914-1915 newspaper articles cited in “Happy Birthday, Charlie Schmutz!” Mighty Casey Baseball, accessible via mightycaseybaseball.com, posted January 2, 2018.

35 Subsequently reported in the Seattle Times, September 3, 1915.

36 As quoted in the Washington Herald, April 9, 1915.

37 The others sent down were Raleigh Atchison, Joe Chabak, and Elmer Brown.

38 By virtue of the two-year contract he signed prior to the 1914 season, Schmutz remained Brooklyn property.

39 As per “National League Notes,” Sporting Life, July 24, 1915. See also, Washington Post, July 7, 1915.

40 As reported in Sporting Life, August 28, 1915, and the Seattle Times, September 1, 1915.

41 “Schmutz will still be the property of Brooklyn but will finish the season here,” reported the Seattle Star, September 3, 1915.

42 Per “Seattle Clinches 1915 Championship,” Tacoma Ledger, September 17, 1915.

43 See “Work of the National Commission,” Sporting Life, March 11, 1916. See also the Macon (Georgia) Telegraph and New Orleans States, March 5, 1916.

44 As per The Oregonian, May 27, 1916.

45 Schmutz’s 1916 strikeouts total comes from Northwestern League stats published in Sporting Life, January 13, 1917. Baseball-Reference has no strikeout data for the 1916 NWL season.

46 As per “Charles Schmutz Sold to Vancouver Club,” Tacoma Ledger, April 18, 1917, and “Schmutz Is a Beaver Now,” Tacoma Times, April 18, 1917.

47 As reported in the Seattle Times, April 22, 1917.

48 Former Seattle High outfielder Ten Million was a workmate/baseball teammate of Schmutz at the company.

49 As variously reported in the Daily (Missoula, Montana) Missoulian, March 10, 1918, Seattle Times, March 17, 1918, Tacoma Ledger, April 10, 1918, and elsewhere.

50 While awaiting embarkation at the French port of Saint-Nazaire, Charlie had a happy reunion with another old friend/teammate, Sergeant Jimmy Agnew.

51 Among other things, Schmutz pitched for Charlie Mullen’s Mt. Vernon club, the 1920 winner of the semipro Big Six Skagit League, and hurled Auburn to the championship of the Valley League the following year. Later, he served as a commissioner (with former Seattle Siwashes boss Dan Dugdale) of the semipro Seattle Community League.

52 See e.g., “Social Notes,” Seattle Times, November 1, 1927, March 18, 1928, February 10, 1931, March 8, 1933, June 29, 1934, and November 5, 1935.

53 See e.g., “Social Notes,” Seattle Times, February 23, 1934 (Europe); February 17, 1935 (San Francisco/Santa Anita racetrack); April 18, 1937 (Mexico).

54 Online state marriage records indicate that the couple was married in Clallam, Washington, on September 3, 1940.

55 As per “Vital Statistics/Divorce Granted,” Seattle Times, October 26, 1945.

56 The Seattle Rainiers were a member of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League. During the late 1930s, Schmutz had been on the booster committee of the Rainiers’ predecessor, the Seattle Indians.

57 Schmutz had offered a hesitant newspaper prediction of victory by his old club, while one-time Yankee Charlie Mullen confidently forecast a New York win in the Series. See the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, September 28, 1955.

58 As per the death certificate contained in the Charlie Schmutz file at the Giamatti Research Center. The immediate cause of death was listed as coronary occlusion due to auricular fibrillation.

59 As per the obituaries published in the Seattle Times and Seattle Post-Intelligencer, June 28, 1962.

60 As per the posthumous player questionnaire completed by brother Ernie Schmutz, and confirmed by Evergreen-Washelli Memorial Park staff to the writer via telephone, October 29, 2018.

Full Name

Charles Otto Schmutz

Born

January 1, 1891 at San Diego, CA (USA)

Died

June 27, 1962 at Seattle, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.