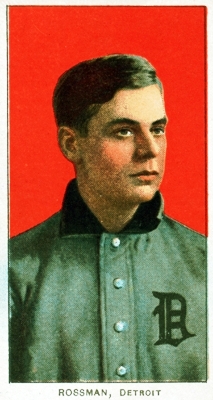

Claude Rossman

Every human being who has lived on this Earth has done so with a shaky psychological underpinning. Most of us manage to hold onto our senses and live out our lives keeping our balance. Then there are those unfortunate ones who lose their psychological balance and go under. Major leaguers are not exempt. Claude Rossman was one of the unfortunates. Sometime after his too-brief major-league career, he had a breakdown. He died in a hospital for the insane at the age of 46. The cause was paresis, or insanity caused by syphilitic alteration of the brain.

Every human being who has lived on this Earth has done so with a shaky psychological underpinning. Most of us manage to hold onto our senses and live out our lives keeping our balance. Then there are those unfortunate ones who lose their psychological balance and go under. Major leaguers are not exempt. Claude Rossman was one of the unfortunates. Sometime after his too-brief major-league career, he had a breakdown. He died in a hospital for the insane at the age of 46. The cause was paresis, or insanity caused by syphilitic alteration of the brain.

Claude Rossman was born on June 17, 1881, in Philmont, New York, a farming and woolen manufacturing village about 100 miles up the Hudson River from New York City. His father, Robert, was a farmer and his mother, Eva, a housewife. Claude had a sister, Daisy, and a brother, DeWitt.

When young Claude came out of the hinterlands of New York, major-league baseball was still in its infancy. The rules of the New York Game, written by Alexander Cartwright and his gentlemen friends, had prevailed over town ball and nine o’ cat. It was the Deadball Era, a game of fine pitching, moving up the runner, stealing bases, bunting. Though home runs were gratefully accepted, it was not the accepted mode for winning ballgames. Rossman would turn out to be a fine bunter and was a typical ballplayer of that time, coached to win in the prevailing style of baseball.

Rossman began his professional playing career in 1903 with the Holyoke (Massachusetts) Paperweights in the Connecticut State League, where he played the outfield and batted .365, banging out 158 hits. In 1904, with the Holyoke team, he batted .291 and was purchased by the Cleveland Naps. Brought up to the Naps at the end of the 1904 season, he appeared in 18 games and had 13 hits in 62 at-bats, for a.210 average.

Sent back to the minors in 1905, Rossman played with the Des Moines Underwriters and the Columbus team, both in the Western League, where he became a first baseman. He batted a combined .358 with the two teams. Rossman secured a spot on the Naps in 1906, this time as a first baseman. He played in 118 games, batting .308. In December 1906, Rossman was sold to the Detroit Tigers. There he joined up with Ty Cobb, Sam Crawford, and Hughie Jennings for the 1907 season, and batted .277 with 69 RBIs as the Tigers won the American League pennant. He played in 153 games, leading the league.

On May 4, 1907, as a baserunner, Rossman was involved in an unusual triple play pulled off by the Chicago White Sox. All the outs were tag outs. Rossman was on third base and Germany Schaefer was on second when batter Boss Schmidt sent a groundball to shortstop George Davis. Rossman headed for home but retreated to third when Davis threw the ball home, but catcher Billy Sullivan tagged him out before he could get back to the base. Schmidt had reached first, rounded the bag and was tagged out at second. Schaefer, meanwhile, ran for home and crashed into pitcher Ed Walsh, who had taken the throw from second. Walsh dropped the ball, but shortstop Davis scopped it up and tagged Schaefer. According to Baseball Triple Plays online, there have been only 13 all-tag-out triple plays in the major leaguess.

Rossman excelled in the 1907 World Series, batting .474 with a .579 slugging percentage on 9 hits, including a triple. He had two runs batted in and scored one. run. Unfortunately Ty Cobb and Sam Crawford did not come through for the Tigers, hitting .200 and .238 respectively. The Tigers fell to the Chicago Cubs in four straight.

In 1908, Rossman experienced the best year of his major-league career. He hit for a.294 batting average, with 33 doubles, a slugging percentage of .419, 71 runs batted in and 13 triples. His doubles total was the second best in the American League. In the 1908 World Series against the Chicago Cubs, he was 4-for-19 (.211) with 3 runs batted in. The Tigers again fell to the Cubs in the Series.

Rossman was an excellent bunter and many times when he would lay down a bunt with Cobb on first, Ty was able to speed to third base. Rossman had great range as a first baseman. His career range factor at first base (assists plus putouts divided by games played) was11.06, almost 3 full points above the average for first basemen of his era. But there was one flaw in his armor as a first sacker. The hazardous throw from the first baseman to second base trying to retire a runner going from first to second on a force play has pained many first basemen. Rossman had a peculiar quirk in those situations. He would sometimes freeze and be unable to throw the ball. This quirk was said to have greatly shortened his career. He was only 28 when he played his last game in the majors. Something ominous and egregious was invading his mind and body that would contribute to his death at an early age.

In 1907, an unsavory incident occurred involving Cobb and Rossman in a game against the Philadelphia Athletics at Columbia Park in Philadelphia in late September. The incident became known as the “when-a-cop-took-a-stroll play.” The A’s and the Tigers were in a tight pennant race. The game was tied 8-8 in the 14th inning. In the bottom of the inning, Harry Davis of the A’s drove a long fly ball to center field, where Sam Crawford misplayed the ball. Part of the overflow crowd was standing in center field, behind ropes, and a policeman was tending to the crowd. The Tigers charged that the policeman had interfered with Crawford, causing him to drop the ball. Arguments followed. Ty Cobb provoked things more by telling Rossman that Monte Cross of the A’s had called Rossman a Jew bastard. Rossman proceeded to punch Cross and was ejected from the game and arrested. (No sources state that Rossman was Jewish.) The umpire, Silk O’Loughlin, ruled against the A’s and the game continued in a tie until the end of the 17th inning, when it was called because of darkness. The Tigers felt vindicated in spite of the tie and went on to win five straight games that helped them win the pennant. After the game, Athletics manager Connie Mack, usually kind and gentle, was enraged and said, “If there ever was such a thing as a crooked baseball game, today would stand as a good example.”

Hughie Jennings reportedly was one of the first managers to fine players. Rossman was one of the first to be fined $50 by Jennings for hitting a home run when he was called on to bunt.

Despite his good year in 1908, Rossman’s prospects with the Tigers took an adverse turn in 1909. Tigers owner Frank Navin told the media, “Claude Rossman is on the market and will be sold to any club which desires his services. Rossman’s throwing has been poor and manager Jennings is reported to have been dissatisfied with his work.” On August 20, Rossman was traded to to the St. Louis Browns for Tom Jones, an infielder. Rossman had played in 84 games for the Tigers at the time and was batting .258 with 39 RBIs. Rossman played only two games in the outfield for the Browns with on hit in eight at-bats, and was sharply criticized by several teammates for his play, upon which he declared that he could not and would not play any further for the Browns. He carried out his threat, and it was the last time he played in the major leagues.

In five major-league seasons, Rossman batted .283, with 523 hits, 80 doubles, 26 triples, 3 homers, 175 runs scored, 238 runs batted in and 49 stolen bases.

Rossman found a hitting groove in the minor leagues. In 1910, he played for the Columbus Senators and then the Minneapolis Millers in the American Association. He appeared in 155 games with a batting average of .278. From 1911 through 1914, he was a fixture with the Millers. In 1911 he.batted a lusty 356. In 1912 he hit.322; In 1913, he batted .302. In all of those seasons, he played in all or most of the Millers’ games. In 1914, he played in 101 games and batted. 252. His baseball career was over.

Something was gnawing and tearing at Claude Rossman’s mind and body. His mental facilities began to deteriorate and his emotional state was declining. He was no longer able to play professional baseball.

Not much is known about Rossman’s life after his baseball career ended, except that he worked as a shipping clerk in 1918 for the Williston Tire and Rubber Company in Minneapolis. We do know that he was admitted to a mental hospital in Poughkeepsie, New York, where he died on January 16, 1928, at the age of 46. There is some confusion on where he was buried. According to family members, he was buried in Mellenville, New York. Others said he was buried in an unknown cemetery somewhere else in upstate New York. An obituary in the New York Times dated January 18, 1928, stated that Rossman had been a patient for several years in the Hudson River State Hospital for the Insane in Poughkeepsie, and that he was to be buried in his hometown of Philmont.

Claude Rossman was a finely tuned athlete, but a misaligned mind did him in. Lee Allen, the late historian at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, kept records of ballplayers’ deaths. His records show that the cause of Rossman’s death was “insane—paralysis,” Or paresis. These were the attributes and agonies that were the makeup of Claude Rossman. The big city took its toll on a lad from the farm. It must have been a lonely road to travel.

Sources

Allen, Lee, former historian, Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York, records of ballplayer deaths.

Baseball Historian, online

Baseball Hall of Fame, Notes on Claude Rossman, Cooperstown, New York,

Baseball Triple Plays, All Tag Outs, online

New York Times obituary January 18, 1928

Old Philmont Baseball Team, online.

The Baseball Page, online

The Bluhm Memorial, Detroit Tigers Hall of Fame, Motown Sport

The Deadball Era, Too Young to Die, online.

Wikipedia, online

Full Name

Claud Rossman

Born

June 17, 1881 at Philmont, NY (USA)

Died

January 16, 1928 at Poughkeepsie, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.