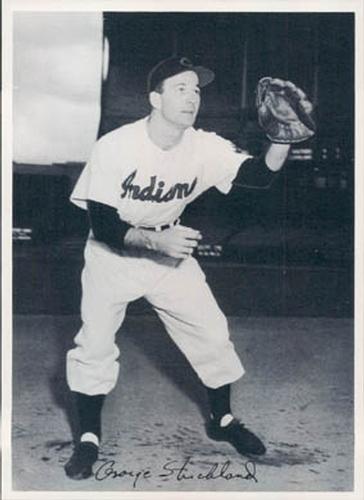

George Strickland

George “Bo” Strickland was the starting shortstop on the 1954 Cleveland Indians team that won the American League pennant and compiled one of baseball’s finest records ever, 111-43. He went hitless (0-for-9) in that season’s World Series, the only one he ever played in, as the Indians were swept by the New York Giants. Strickland was a good glove man, a utility infielder highly regarded for his defense who despite being a weak hitter (.224 career batting average) played ten major-league seasons.

George “Bo” Strickland was the starting shortstop on the 1954 Cleveland Indians team that won the American League pennant and compiled one of baseball’s finest records ever, 111-43. He went hitless (0-for-9) in that season’s World Series, the only one he ever played in, as the Indians were swept by the New York Giants. Strickland was a good glove man, a utility infielder highly regarded for his defense who despite being a weak hitter (.224 career batting average) played ten major-league seasons.

The New Orleans native had his finest season in 1953, when he turned 103 double plays, and hit .284. In 1955 he eked out only a .209 batting average but had the highest fielding percentage for shortstops in the major leagues, .976. Strickland was credited with helping to turn around the Indians’ defense and being a significant factor in the team’s 1952 and 1959 pennant runs. After his playing career ended, Strickland scouted for one year and coached for ten with the Indians, the Minnesota Twins, and the Kansas City Royals. In 1964 he became the first New Orleans native to manage in the majors when he filled in for an ailing Birdie Tebbetts.

Strickland kept a low profile as far as the general public was concerned, but to those who knew him, he was a loyal friend with a great sense of humor. Later in life, when he attended sports luncheons in New Orleans with retired athletes, said a New Orleans sportswriter, “He was often the life of the party, and had the group in stitches. Everybody wanted to sit next to George.”[fn]Nakia Hogan, New Orleans Times-Picayune, February 22, 2010, quoting New Orleans sportswriter Peter Barrouquere in Strickland’s obituary. [/fn]

George Bevan Strickland was born on January 10, 1926, in New Orleans. His father, Harold Lind “Harry” Strickland, was a police officer assigned to Pelican Stadium where the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern Association played. His mother, Imelda (Bevan) Strickland, was a homemaker. George had a sister, Rita, six years older, and a brother, Harold L., Jr., four years older.

The Strickland family lived in the Third Ward, the crowded central business district in the Crescent City. “Like many families then, ours was poor due to the Great Depression. We didn’t have a radio, so we played a lot out of doors,” Strickland told an interviewer. His favorite activities were baseball, basketball, and fishing. His earliest memory of playing ball was of his father taking him to a wide median on a major street and spinning bottle caps at him to hit with a sawed-off broom handle.[fn]Information provided by John T. Strickland, son.[/fn]

George got his nickname, Bo, for having numerous “bobos” (scratches, scrapes, and bruises) when he was a child. “When I was little,” he related, “I liked to visit my grandma at the casket factory where she worked, and her boss said he’d never seen a little fella with so many bobos. The nickname stuck and everyone started calling me Bobo, later shortened to Bo.”[fn]George Strickland oral history recording by Rick Bradley for SABR, February 1993.[/fn] But by the time he was a ninth-grader and tried out for his S.J. Peters High School baseball team, he preferred to be called by his middle name, Bevan. Strickland didn’t make the team in the ninth grade, but did make the varsity as a sophomore in 1941. His coach, Dave Dahlgren, liked his fielding ability. “He might be small,” said Dahlgren, “but just try to get a ball past him!”[fn]Nate Cohen, “What’s What: When Strickland Was Called ‘Baby,’ ” New Orleans Times-Picayune, April 12, 1964, 108.[/fn]

The 1941 Peters nine made its way to the New Orleans City high school finals. Teammate Mel Parnell, a future Boston Red Sox star pitcher, said, the team “was so good, we took things easy; we fooled around too much and were beaten.”[fn]New OrleansTimes-Picayune, undated.[/fn] The next year, though, with Strickland as the team captain, Peters won the city title. Strickland was still growing; he didn’t reach his adult height of 6-feet-1 and weight of 175 pounds until a few years later.[fn]Christian Science Monitor, March 26, 1948.[/fn]

In 1943 Strickland played American Legion ball with Aloysius Jax Post. The team won the Legion tournament regional finals at Cape Girardeau, Missouri, then finished fourth in the national finals at Miles City, Montana. Strickland made the All-Legion second team as a utility infielder,[fn]New Orleans Times-Picayune, July 18, 1943, 19.[/fn] and shortly afterward he signed a contract with the New Orleans Pelicans, a Brooklyn Dodgers farm team. He played in only three games for the Pelicans, then before the 1944 season he was drafted into the US Navy. He spent 16 months on the Pacific island of Saipan as a mailman specialist. While he was there, his older brother, Harry, an Army paratrooper, was killed in action in the Pacific.[fn]New Orleans Times-Picayune, undated.[/fn] Discharged from the Navy in May 1946, Strickland returned to the Pelicans, who had become a Boston Red Sox affiliate. He resumed playing third base and batted.242 in 78 games.

Strickland went to spring training with the Red Sox in 1947, and competed for a backup infield position, but eventually was sent to Scranton of the Class A Eastern League, where he displayed a strong arm but batted.235 in his first full minor-league season. He had difficulty at third base coming in on infield taps and eventually switched positions with Scranton shortstop Fred Hatfield, a move that benefited both players.[fn]Danny Peary, We Played the Game (New York: Hyperion Books, 1994), 128.[/fn] Strickland started the 1948 season with Scranton, but was promoted after several weeks to the Triple-A Louisville Colonels and given the regular shortstop job. He fielded well but batted just .237. The next season Strickland was sent back to Double-A ball, the Birmingham Barons in the Southern Association. For Strickland it was a wake-up call that led to his best season in the minor leagues. He hit .261 in 128 games for the Barons, and was named the Southern Association’s second-team all-star shortstop. After the 1949 season the Pittsburgh Pirates selected Strickland in the Rule 5 draft. The Pirates were regarded as one of baseball’s worst teams then, but Strickland didn’t care, because “they wore major-league uniforms!”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

Strickland made the Pirates squad in 1950 but his major-league debut was delayed until May 7 after a recurrence of a fungal infection he had suffered in the Army. In his debut, against the Dodgers in Brooklyn, he entered the game as a defensive replacement in the eighth inning. He did the same the next day and got to bat but drew a walk. In his first major-league at-bat, on May 14, he hit a two-run pinch-hit single in the ninth inning off the Chicago Cubs’ Paul Minner that won the game, 6-5. But he played sparingly, appearing in just 23 games, and started only six games at shortstop. He was 3-for-27, for a .111 batting average.

In 1951 the Korean War and the resultant draft of young players worked in Strickland’s favor. Since he had served in World War II he would have been among the last to be called for duty. Eight games into the 1951 season, the Pirates traded shortstop Stan Rojek, and with Danny O’Connell serving a two-year Army hitch, Strickland became the starting shortstop. He played in 138 games, hit just .216, led the team with 83 strikeouts, and made 37 errors, second only to New York Giants rookie Alvin Dark’s 45. Most of Strickland’s errors occurred because he rushed his throws, and not because of poor fielding. Playing in Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, he got into the bad habit of trying to pull everything, which resulted in lots of strikeouts and easy fly balls to left field. Hitting coach Paul Waner tried to teach him to “hit the ball where it was pitched” to little avail.

The woeful Pirates desperately needed hitting. Then they drafted Dick Groat, a local boy, an All-American basketball player, and all-conference baseball player at Duke University, and Strickland became expendable. On August 18, 1952, hitting .177, he was traded to the Indians with pitcher Ted Wilks for second baseman Johnny Berardino and $50,000. Later the Pirates also received minor league pitcher Charles Sipple. Tony Cuccinello, the Indians’ infield coach, liked Strickland and had recommended that the team acquire Strickland. A former National League coach, Cuccinello had watched Strickland and felt that he had the “soft” hands necessary to be a good fielder, and that his throwing faults could be corrected.

The Indians were built on offense – they could easily accommodate Strickland’s lack of offensive production to shore up the infield. They were last in the league in turning double plays, and each infielder led the league in errors at his position. On August 24, 1952, the Indians committed seven errors; handed the Senators seven runs, and lost, 9-8. Manager Al Lopez inserted Strickland at shortstop the next day. He didn’t get a hit, but he turned three nifty double plays, and the team won behind Bob Lemon, 7-2. The next day he broke a scoreless tie with the Philadelphia Athletics and smacked his first home run as an Indian, a two-out, two-run shot off Bobby Shantz. On September 27, against the Detroit Tigers, he burnished his fielding credentials by taking part in five double plays, tying a record at the time that has since been broken. With Strickland as the regular shortstop, the Indians became part of the race for the American League pennant, which eventually was won by the New York Yankees.

Strickland had his most productive year in 1953, batting .284, and leading American League shortstops in turning double plays with 103. Then, in the marvelous season of 1954, he slipped back to his usual level (.213), but contributed more than his share of timely hits . Early in the season the Cleveland Plain Dealer noted that though he had only 16 hits at the point, he had 15 RBIs.

On July 23 Strickland’s jaw was broken in a game in Yankee Stadium when he was hit by a throw from Yankees pitcher Marlin Stuart while sliding into third base. He was out for more than a month and lost 15 pounds. He missed five weeks and didn’t return until September 5. He never got his timing back at the plate, and in the World Series, in which the Indians were swept by the Giants, he was hitless in nine at-bats.

In Game Three he made a throwing error in the first inning that let in the first run in the 6-2 loss to the Giants. Some sportswriters suggested that he was out of position in the third inning when the Giants’ Don Mueller executed a perfect hit-and-run play. Others came to his defense, saying that it was normal for a shortstop to cheat toward second base when he is looking for a double-play ball, and that Mueller, one of the finest place hitters in the game at the time, had pushed the ball perfectly through the vacated spot. Strickland was replaced at shortstop in Game Four by Sam Dente, who had started 48 games at shortstop during the season.

In 1955 Strickland struggled at the plate again (.209), but led American League shortstops in fielding percentage. In 1956, he turned 30 years old and lost his starting shortstop job when the Indians obtained shortstop Chico Carrasquel in a trade over the winter. Strickland was relegated to a utility role. He filled in at shortstop when Carrasquel’s bat went cold, or for Bobby Avila at second base when Avila’s back was sore. He played in 85 games and batted .211.

Strickland hit well in spring training of 1957 and was named the outstanding player of camp. He was moved to second base but was injured early in the season. In September he replaced Carrasquel when Chico was benched for “not charging ground balls,” but overall Strickland’s playing time was greatly diminished (89 games).

In 1958, at the age of 32, Strickland asked to be placed on the voluntarily retired list. He and Lorraine had adopted a child, John Thomas, their first. His diminished playing time, and a new manager, Bobby Bragan, also influenced the decision. In Strickland’s absence, the Indians converted center fielder Woody Held into a shortstop. Strickland, meanwhile, took a job selling sporting goods at the Maison-Blanche department store in downtown New Orleans. That fall he applied for a job working in the pari-mutuel windows at The Fairgrounds race track in New Orleans that fall and winter. (He sought and received permission from the baseball commissioner’s office, which in general frowned on players working in the gambling world.) Strickland worked at the race track until he retired in 1988 as assistant manager of the pari-mutuel department. Meanwhile, though, in 1959, after spring training had begun, he asked the Indians to reinstate him as a player. The Indians allowed him to compete for a job as a nonroster player. Strickland played well in spring training and was added to the roster. He continued to hit well, though everyone expected his average to plummet as it almost always did.

Cleveland stormed out of the gate that year to the lead in the American League. Strickland played a major part in it. The infield consisted of Vic Power at first base, Billy Martin at second, Strickland at short, subbing for Woody Held (recovering from surgery), and Randy Jackson at third base. Near the end of May, Strickland was batting .355. Billy Martin said the best season he ever had as a fielder was 1959 when he had Strickland at short and Vic Power at first.[fn]Max Nichols, “Timely Tips From Battling Billy,” The Sporting News, March 28, 1962, 17.[/fn]

Then Strickland pulled a leg muscle and was replaced by Granny Hamner at shortstop. Soon Woody Held was back at shortstop, and Strickland moved to third base. The Indians stayed in the thick of the pennant race until a series at the end of August when they lost four straight to the Chicago White Sox, dashing their hopes for winning the pennant.

In April 1960 Strickland returned for another season with the Indians as insurance to play shortstop if the Indians had to move Woody Held to center field in case Jimmy Piersall hadn’t signed. Piersall signed late and played center field, but an injury to Held gave Strickland yet another opportunity to play shortstop for 14 games. He also filled in at third base for 14 games and at second base for two games. His batting average plummeted to its usual anemic state. When Held returned to play shortstop, the writing was on the wall; there was no need to keep Strickland. He played his final game on July 23, 1960. He had a career batting average of only .224, but his skill in the infield allowed him to play 971 games over ten seasons.

Strickland was the last remaining member of the Indians who’d played for the team before Frank “Trader” Lane began as general manager in November 1957. “They said I was brittle, but I lasted ten years in the majors and that’s something I’m proud of,” he said years later.[fn]Rick Bradley interview.[/fn]

After he was released, Strickland scouted National League clubs for the Indians in 1960. Sam Mele, a friend from his days in the Red Sox minor-league system, and then the Minnesota Twins manager, added him as third-base and infield coach for the 1962 season.

On October 13, 1962, Birdie Tebbetts returned as the Indians’ manager. His first move was to hire Strickland from the Twins. On July 10 Tebbetts was out sick, and Strickland filled in as manager, becoming the first native of New Orleans to manage in the major leagues. After Tebbetts recovered, he went back to his third-base coaching duties. In 1964, when Birdie Tebbetts again took ill, Strickland again filled in.

In December of 1965 Strickland was reported to be the top candidate to manage the Chicago White Sox, but Eddie Stanky got the job. On August 19, 1966, Tebbetts was fired as manager of the Indians and Strickland succeeded him. The Indians went 15-24 under Strickland. His overall record as an Indians manager was 48-63. Joe Adcock was named manager the following season, 1967, and Strickland went back to coaching third base. His last season coaching for the Indians was 1969. In 1970 he joined his Indians friend Bob Lemon as a coach with the Kansas City Royals. When Lemon was fired after the 1972 season, Strickland was also released, and he retired from baseball for good. He told Lemon not to call him even if he got another job (Lemon did get another job, managing the Yankees), because he was going home to New Orleans to be with his family. He’d earned the maximum pension after 20 years in the major leagues. He had also continued to work at the Fairgrounds Race Track, where he had become assistant manager of the pari-mutuel department.

For a decade or so Strickland was a popular speaker for a group that met for lunch every week in New Orleans. The group included former pitcher Mel Parnell, Louisiana baseball historian Arthur Schott, sportswriter Peter Barrouquere, retired football players, a boxing referee, and a race-horse trainer.

“Everything in baseball turned out the best for me,” said the modest, soft-spoken baseball lifer with an infectious enthusiasm for the game. He died on February 21, 2010. He was survived by his son, John Thomas Strickland, and his family, and was buried in Greenwood Cemetery, New Orleans. His beloved wife, Lorraine, had predeceased him by five years.

This biography is included in the book Pitching to the Pennant: The 1954 Cleveland Indians (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Joseph Wancho. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Sources

Much of the information in this biography was taken from an interview with Strickland conducted by SABR member Rick Bradley in February 1993.

Written correspondence with George Strickland by the author, November 2009.

E-mail correspondence with George Strickland’s son, John Thomas Strickland, March-October 2010.

Frank Gibbons, “Playmaker Strickland Bargain of Year; 10-G Prize Keys Indians Infield,” Baseball Digest, September 1953, 5-8.

Carol Hart, “Jays Place Five on All-Legion Ball Team,” New OrleansTimes-Picayune, July 18, 1943, 19.

Hal Lebovitz, “Strickland Fooled Them All,” Sport, September 1954, 64-66.

Andrew O’Toole, Branch Rickey in Pittsburgh: Baseball’s Trailblazing General Manager for the Pirates, 1950-1955 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2000), 178.

Waddell Summers, “Stars Abounded on 1941-42 Peters Baseball Team,” New OrleansTimes-Picayune, June 26, 1965.

Also consulted were Strickland’s clippings file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and listings on Baseball-Reference.com, and Retrosheet.com.

Full Name

George Bevan Strickland

Born

January 10, 1926 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

Died

February 21, 2010 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.