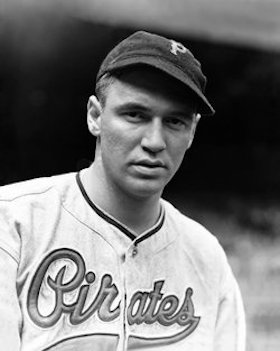

Russ Bauers

Northeastern Wisconsin’s growth followed on the heels of the Midwest’s economic hub, Chicago. Timber from the extensive white pine forests built the Windy City while the growing metropolis’ needs fueled the economies of small lumber boomtowns peppering the north—towns with names like Mountain, Soperton, Padus, Carter, and Wabeno. In a similar manner, baseball’s development depended upon pulling human resources from the wide open regions of the nation, bringing work and wages to the talent scattered along the back roads of this country. Russ Bauers became one such resource, a raw material that would be shaped in the forges of professional ball. Escaping the low wages and hard work of his peers, Russ rode the rails to the big leagues in Chicago, Pittsburgh, and, briefly, St Louis.

Northeastern Wisconsin’s growth followed on the heels of the Midwest’s economic hub, Chicago. Timber from the extensive white pine forests built the Windy City while the growing metropolis’ needs fueled the economies of small lumber boomtowns peppering the north—towns with names like Mountain, Soperton, Padus, Carter, and Wabeno. In a similar manner, baseball’s development depended upon pulling human resources from the wide open regions of the nation, bringing work and wages to the talent scattered along the back roads of this country. Russ Bauers became one such resource, a raw material that would be shaped in the forges of professional ball. Escaping the low wages and hard work of his peers, Russ rode the rails to the big leagues in Chicago, Pittsburgh, and, briefly, St Louis.

Born May 10, 1914 in the village of Townsend, Wisconsin, Russell Lee Bauers would witness how hard people could work for what they desired. His birth certificate gives his name as “Leonard Alfred Lundquist,” though Forest County records claim that on January 27, 1915, he was “baptized and received the name of Russel Lee,” though spelling the first name with double Ls became the norm.1 After father Charles Lundquist died on August 9, 1917, mother Freda Ihlenfeldt remarried George Bauers and young Russ assumed the “Bauers” surname. His stepfather labored as a foreman for the Holt Lumber Company and, later, operated a popular Lakewood, Wisconsin tavern.

Russ’s mother worked as a cook at a farm just east of Lakewood. That farm, now a golf course, offered young Russ a log cabin wall against which he could practice pitching. He learned to hurl at certain spots on the logs so the ball would bounce back to him, improving his control in the process.

The Lakewood school only offered classes through 10th grade. George Bauers wanted Russ to attend his alma mater, a larger school 30 miles south in Oconto for his final two years. In Oconto, Russ played football as an end and basketball as center, along with baseball, graduating in 1933. In a District Championship for Oconto, the 15-year-old struck out 19 in seven innings, for a decisive win against Green Bay’s West High School. He also played for local teams. “I was playing first base with the Lakewood town team,” he told The Sporting News, “when our pitcher was knocked out of the box one day.” When his teammates, who knew he could throw heat, asked him to pitch, he “stopped the opposing team from any more scoring,” becoming the pitcher for the club.2 Russ considered playing basketball but knew the costs of college would prove insurmountable. So he set off for greener pastures with the Chicago Mills, a semipro baseball outfit that played its games at 4700 Lake Street, on the Windy City’s growing near-northwest side. With the Mills, Bauers—sometimes identified as “Speed Bowers” or “Russell Bowers” in the local press–pitched against a variety of opponents including Benton Harbor’s House of David team, Nashville Negro League champions, as well as teams from Indiana, Wisconsin, and Illinois. The offseason found him back home, working in the lumber camps. In 1935, probably lacking sound advice from anyone in the know, he signed a contract with the Philadelphia Phillies as an amateur.

The inexperienced right-hander who batted lefty found an ally in Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis who granted Russ “free agency,” essentially ending the young Badger’s indenture to the Phillies on February 3, 1936. A month later, the 6-foot-4 Wisconsin boy would become the 10th youngest player in the National League when he signed with the Pittsburgh Pirates. The Pirates’ interest in Bauers was likely not accidental, fueled by player-manager Pie Traynor’s scouting trips. Traynor had told The Sporting News, “We’re going to spend our time hunting for a couple of fellows who can throw that ball past hitters with plenty of smoke on it.”3 By 1936, Bauers showed up on Traynor’s radar, even earning a comparison to Dizzy Dean from the Hall of Fame third baseman. That year, after being retrieved from their Scranton farm team, he started in one outing for the Bucs, pitching on August 20 and giving up five earned runs in 1 1/3 innings. The Sporting News concluded, “Bauers is promising, but he is still pretty much of a kid, and may need another summer in fast minor league company before he will be ripe for a prolonged period of usefulness under the big tent.”4

1937, Bauers’ true rookie year, seemed a harbinger of a great future. Destined for some seasoning in the minors, Bauers told The Sporting News, “Yes, I knew I was ticketed for Montreal, but I had already made up my mind that I was going to stick with the Pirates.”5 With help from veteran catcher Johnny Gooch, picked up as Pittsburgh’s pitching coach, Bauers learned to throw overhand in addition to his sidearm delivery.6 Bauers’ first win for Pittsburgh came on June 8, when his six-hitter complete game bested the Phillies, 8-1. Bauers made novice mistakes. One critic remarked, “[Bauers] would let up on certain batters when he should have been bearing down.”7 But Traynor, Gooch, and others drilled him as hard as they could. Honus Wagner said of Bauers: “Now there’s a comer. He’s got a great curve ball. Fine young fellow, too. But awful bashful. Why, I’m about the only one on the club to whom he’ll talk much. Just says ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ to most people.”8 On September 5, the North Western Railroad hauled 300 Oconto County fans to Chicago on the “Russ Bauers Special,” each paying $4.55 train fare and $1.65 for a box seat behind the visiting Bucs dugout for a Sunday double header that Pittsburgh swept. The northern fans witnessed Red Lucas, rather than their hometown hero, hurl a shutout in the first game, and Ed Brandt win the second. For the 1937 season, Bauers went 13-6 while his ERA of 2.88, from 187 innings worked, ranked fourth in the National League and first for the Pirates.

In 1938, he led the National League in errors committed by a pitcher with six, while amassing a 13-14 record in 34 starts, with a team-leading 243 innings worked. His ERA, 3.07, ranked eighth in the league.9 Bauers peppered his mediocre performances with bursts of exceptionality, such as on August 10 when the papers wrote that “on one of his red hot days” Bauers “who lost six of his first seven games didn’t allow a hit until the fifth, when Johnny Mize singled through the box.”10

Going into September 1938, the Bucs had a seven-game lead in the pennant race. But the Cubs ended that with their near-mythic autumn, despite Bauers winning four in September, including a shutout against the Phillies on September 18 in which he allowed only four hits.

Reporters—many who played up his identity as a lumberjack, an “indian,” and a wild thrower–kept track of Bauers’ hijinks, hoping to label him a clueless rube, a clown, or a drunkard. Many noticed that Bauers’ head simply wasn’t in the game, a view supported anecdotally. In an exhibition game, Bauers lobbed a fastball to Joe “Ducky” Medwick who stroked the ball out of the lot. He then consulted with his catcher: “Gosh, that bozo sure smacked that one. Who is he?”11 Russ gained a reputation as a guy who lived in the moment, doing little to understand his opponents or prepare himself for competition.

Traynor had his mind set on improving his pitching staff, if for no other reason than to save his job. To this end, he swapped catchers, sending Al Todd to Boston for Ray Mueller. The manager reasoned, “Mueller is magic with pitchers, and that is what is needed most. Three of the mound men—Russ Bauers, Joe Bowman and Bob Klinger—need a soothing voice and a smart teammate to steady them in the pinches. If Mueller can do that, Pittsburgh will be greatly strengthened defensively.”12 The triad of hurlers had won 28 games in ’38 and Traynor figured they’d win 40 in ’39 (when they collectively went 26-35).

In 1939, Russ only played in 15 games, winning two and losing four. Nagging injuries in his arm hampered his play and kept him benched. After the successful ’37 and ’38 seasons, management began to see Bauers as a problem that needed solving.

Bauers did little to help himself, committing more errors off the field than on. Early in 1938, he burned his hand lighting a match. On a train trip, he wrenched his left knee wrestling with one of the Waner brothers, leading to suspension without pay until he could pitch again. He overworked his arm, trying to speed his recovery, winding up with a sore arm and knee. On December 4, 1939, he totaled his Buick sedan on the icy roads south of Carter, Wisconsin, a few miles from his birthplace. Bauers lost a lot of blood and smacked his head, giving doctors good reason to worry about his welfare. But Russ bounced back, perhaps too quickly for his own good. His career may have benefited from more time to for recuperation.

Before 1939 closed shop, Bauers decided he’d recovered from the accident, writing Pirates club president Bill Benswanger that “he received only a slight cut on the side of his head and that he was ‘feeling fine and in good shape.’”13 By February, he was planning on proving his mettle at training in San Bernardino, California, though refusing to sign his contract until he felt his arm had “fully recovered” as he wanted to avoid “going through another season like that of 1939.”14 Manager Frank Frisch, who as a rule refused to take unsigned players to training camp, made an exception in Bauers’ case and found himself pleased with Russ’s performance in an exhibition game against Chicago’s White Sox in Kansas City.15 Bauers signed his contract in April. He pitched 30 2/3 innings that season for the Pirates with two losses and zero wins.

On January 25, 1941, Russ married a young woman he’d met at dances in Townsend, Virginia Geiter of nearby Wabeno. The newlyweds recognized that 1941 was a time to take the game more seriously. In June, though, he was sent to Jersey City’s International League team to cure his erratic pitching. The Associated Press reported, “Russ simply was too good to release outright yet too wild to be useful.”16 Bauers pitched only 37 1/3 innings for Pittsburgh that season, adding one win and three losses to his totals.

1942 found Bauers back in the minors, throwing for the Albany Senators of the Eastern Region “where a late-season surge – which included six wins in a row and back-to-back two hitters – prompted a recall to the Pirates at the close of the season.”17 Around this time, x-rays revealed a growth responsible for the arm pains that had hampered Bauers’ pitching, a problem remedied with simple surgery.

He didn’t work in the big leagues in 1942, or the next three years as he was inducted into military service early on May 31, 1943. During training, Bauers pitched for the Camp Grant team in Illinois. Then, in January 1944, he joined the Detachment Medical Depot of the 90th General Hospital in England. His unit followed the Allied forces until VE day; Private Bauers learned of Germany’s surrender on French soil. That summer, he suited up for the Overseas Invasion Service Expedition (OISE) All-Stars, a ragtag collection of players—two major leaguers, Bauers and “Subway” Sam Nahem, two Negro League stars, Leon Day of the Newark Eagles and Kansas City Monarch Willard Brown, and various enlistees—who played their way to the European Theater World Series in September against a Third Army team stacked with pros, including Harry Walker and Ewell Blackwell. The underdog OISE All-Stars lost the first game, in Nuremberg’s Hitler Youth Stadium which had been renovated and re-christened Soldier’s Field, but came back to win the second. The Series moved to France where the teams split a pair to tie the Series at 2-2. The Third Army team, the “Red Circlers,” opted for the fifth game in Nuremberg. Down by one run, Nahem allowed the Third Army to load the bases in the fourth before wisely taking himself off the mound. Bauers took over, pulling the All-Stars out of the fix and holding their opponents scoreless for the remainder. The desegregated OISE All-Stars celebrated their ETO World Series victory in France, all joining Brigadier General Charles Thrasher for steaks and champagne.

Aboard the “Maryville Victory,” Army Staff Sergeant Russell Bauers returned from the war, steaming from Marseille, arriving in New York City on December 16, 1945.18 If he dreamed of rejoining the crew of the Pirates, he only had three months to savor those fantasies.

Sportswriter Robert Weintraub characterizes early 1946 as a time of ulcers and nail biting for many ballplayers. “Never had so many been after so few jobs. Nobody felt safe.”19 Pre-war players vied with their wartime replacements as well as the new cohort of players. With more talent to choose from, the overcrowded majors were getting ready to clean house.

On March 21, 1946, Ray L. Kennedy, the Bucs’ general manager, released several players, including Bauers, who would not join the club for spring training.20 By now a veteran in two senses of the word, Bauers had to find another mound. Fortunately, the Chicago Cubs picked him up on July 3 of 1946, and he pitched in 15 games for the season, though only starting in two. One of those starts, on September 2, found Bauers throwing all nine for a 7-3 decision, his first win as a Cub, against his former employer, the Pirates, at Forbes Field. Russ seemed back in form, giving up seven hits but only three earned runs, while knocking a right-field double that drove Bill Nicholson and Marv Rickert home for two RBIs. With the Cubs taking third place in the National League, Russ Bauers took home $294.33, his share of the Commissioner’s dispersal of World Series receipts.

The Cubs let Bauers go on October 5, 1948. From 1949 to 1951, he worked for the St Louis Browns, pitching in only one game as a major leaguer—a 12-4 trouncing by the Philadelphia Athletics on May 6, 1950. Russ pitched the final two innings. 1950 also found him hurling in the Cuban Winter League. He went 13-6 for their Baltimore Orioles minor-league team in 1950, leading some to reason that the Browns who rarely won more than 60 games in a season (58-96 in ’50) might improve in 1951 (when they went 52-102). But St Louis released Bauers to the International League’s Toronto franchise on April 10, 1951.21

For the remainder of 1951, Bauers pitched for the International League’s Maple Leafs. In July, he tossed seven innings of no-hit ball against the Springfield Cubs. The first Cubs batter in the eighth, Jack Wallaesa, hit a shot that Bauers bungled, but the scorer scribed as an error, riling up the Cubs fans. Fortunately for them, the next Cubby singled to left with the Cubs dugout sarcastically yelling, “Error!” Russ salvaged the 1-0 win. Bauers’ main problem with the Leafs was finding offensive support. When he lost, it was commonly by a single run in a low-scoring game; a few powerhouses behind him might have elevated Russ back into the majors.

In 1955, Russ tried his hand at managing a Basin League team in Chamberlain, South Dakota, but decided he’d had enough baseball when the season ended. Reynolds Aluminum pursued him to take an office position for them in Chicago. Bauers wanted to work with his hands, so he talked them into letting him fix equipment which he did until retiring in 1978.

Over the course of 15 years in and out of the majors, Russ Bauers pitched 129 major league games, all but one in the National League. He earned a career ERA of 3.53, won 31 and lost 30, and had 300 strikeouts in 599 innings worked. Years after playing, he identified Enos Slaughter as “the toughest hitter he ever faced.”22

On January 21, 1995, at the Edward Hines Jr. Veterans Administration Hospital of Maywood IL, Russ Bauers’ heart failed.23 His wife Virginia joined him in death in 2012, while his children Andrea Pletzke and Bob Bauers still live, along with numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Russ and Virginia are interred in Wabeno’s Trinity Evangelical Lutheran cemetery, beneath a granite monument depicting a swinging batter and praying hands.

Sources

Much thanks to Andrea Pletzke and Bob Bauers who shared memories and family resources most generously. In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted retrosheet.org, sabr.org, and Thielke, Tom, A History of Lakewood, Wisconsin: Small Town Success in the Northwoods, Published by Author, 2009.

Notes

1 Birth Certificate and accompanying documents for “Leonard Alfred Lundquist,” Department of Health—Bureau of Vital Statistics, State of Wisconsin, County of Oconto.

2 Carl Felker, “Lumberjack Bauers Unlimbers New Delivery Under Gooch’s Tutelage to Win Job on Bucs,” The Sporting News, May 6, 1937.

3 Pittsburgh Press, June 20, 1934.

4 Ralph Davis, “Pirates May Let Big Poison Go to Land Star Pitcher; Other Changes Certain,” The Sporting News, September 24, 1936.

5 The Sporting News, May 6, 1937.

6 The Sporting News, May 6, 1937.

7 Charles Doyle, “Bauers Takes Slice of Praise from Pie,” The Sporting News, August 26, 1937.

8 The Sporting News, May 6, 1937.

9 baseball-reference.com

10 George Kirksey, “Yanks and Pirates Breeze on Despite Southpaw Jinx,” Berkeley Daily Gazette, August 10, 1938.

11 Duke Moran, “Russ Bauers is Sent to Minors,” Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune, June 11, 1941.

12 Jack Guenther, “Pie Traynor Counts His Pirates As Top Finisher,” Altoona Mirror, March 25, 1939.

13 “Pitcher Russ Bauers Ready for Work,” Racine Journal Times, December 28, 1939.

14 “Bauers to Train With Pirates to Test Arm,” Oshkosh Daily Northwestern, February 22, 1940.

15 “Russ Bauers Reports to Aid Pirate’s Team,” Altoona Mirror, April 18, 1940.

16 Duke Moran, “Russ Bauers is Sent to Minors,” Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune, June 11, 1941.

17 baseballinwartime.com

18 ancestry.org

19 Robert Weintraub, The Victory Season: The End of World War II and the Birth of Baseball’s Golden Age (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2013), 13.

20 “Pirates Cut Squad,” Bluefield Daily Telegraph, March 22, 1946.

21 “Inside Baseball Training Camps,” Moberly Monitor-Index and Democrat, April 10, 1951.

22 Bob McGinn, “Where are you now Russ Bauers.” Green Bay Press—Gazette, May 23, 1982: 38.

23 Chicago Tribune, (January 23, 1995).

Full Name

Russell Lee Bauers

Born

May 10, 1914 at Townsend, WI (USA)

Died

January 21, 1995 at Hines, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.