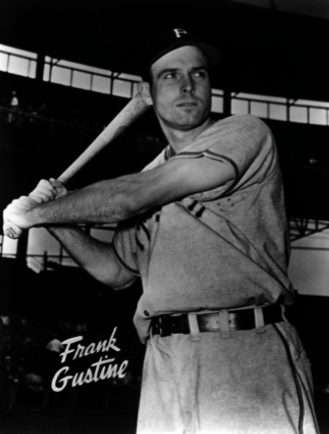

Frankie Gustine

“Baseball had always been in my blood,” said versatile infielder Frankie Gustine, who signed with the Pittsburgh Pirates as a 16-year-old athletic prodigy in 1936. One of the most popular Pirates of his era, Gustine debuted as a September call-up in 1939 and was named to three consecutive NL All-Star teams (1946-1948) as a second baseman and third baseman. A rough-and-tumble hustler whose play harkened back to an earlier generation, he was known for his infectious, competitive spirit, and was recognized as the cornerstone of the Pirates’ infield throughout the 1940s.

“Baseball had always been in my blood,” said versatile infielder Frankie Gustine, who signed with the Pittsburgh Pirates as a 16-year-old athletic prodigy in 1936. One of the most popular Pirates of his era, Gustine debuted as a September call-up in 1939 and was named to three consecutive NL All-Star teams (1946-1948) as a second baseman and third baseman. A rough-and-tumble hustler whose play harkened back to an earlier generation, he was known for his infectious, competitive spirit, and was recognized as the cornerstone of the Pirates’ infield throughout the 1940s.

Frank William Gustine (pronounced with a hard “G”) was born on February 20, 1920, in Hoopeston, founded as a small railroad outpost in east-central Illinois about five miles from the Indiana border. He was the second of two children born to Harry and Zelda (Forshier) Gustine, both native Illinoisans. Marjorie, Frankie’s only sibling and one year younger, developed a serious case of whooping cough as a toddler and ultimately went deaf. Around 1927, in search of proper medical care and education for her, the Gustines moved to the Englewood neighborhood on the south side of Chicago, which is where Frankie grew up. His father worked as a machinist in a factory while his mother was a waitress in a local school. Frankie was an athletic youngster who dreamed about playing big-league baseball. “I kept scrapbooks of all the stars and gave special prominence to Pie Traynor because he was my idol,” said Gustine.1

As a youth Gustine gravitated to third base and modeled his game after his hero. According to his family, he spent his summers back in Hoopeston, where he began to play baseball for the American Can Company in a local industrial league by the age of 12. At Parker High School in Chicago, Gustine excelled as a forward in basketball and played on the tennis and golf teams, but his passion was baseball. He made a name for himself as a bullet-throwing third sacker and occasional second baseman and shortstop on his school team, which also included future big-league pitcher Bob Carpenter; he was also a standout in local late-summer and fall sandlot leagues. The nearby University of Chicago recruited the prized athlete and offered him a basketball scholarship, but he turned it down to concentrate on baseball. Gustine’s big break came from his next-door neighbor, Sam Roberts, an unofficial scout for the Pittsburgh Pirates and a good friend of Traynor. “I was a 14-year old kid … in 1934 when I first met Pie,” Gustine recalled.2 Traynor promised to keep close tabs on the youngster’s development. Two years later, Traynor, then manager of the Pirates, met Gustine again under much more serious circumstances. “Traynor talked to me for about two hours at the Pirates’ hotel and it was the thrill of my life. He invited me to go out to Wrigley Field and work out the next day,” Gustine told sportswriter Dick Farrington. “I guess he liked me, because before he left town with his team, he had my mother sign a contract so I could report to the Hutchinson farm club of the Pirates in the spring of 1937.”3

While his classmates were anxiously awaiting graduation from high school, Gustine was preparing for spring training with the Hutchinson (Kansas) Larks in the Class C Western Association less than two months after his 17th birthday. In his first year of professional ball he displayed the infield versatility that would eventually lead him to a big-league career spanning 12 seasons. Gustine began the 1937 campaign as a third baseman for the Paducah Indians of the Class D Kentucky-Illinois-Indiana (Kitty) League, and then was recalled in midseason to Hutchinson, for whom he played shortstop. He batted a combined .256. The Larks’ youngest fielder the following season, Gustine showed more pop in his bat in 1938 and swiped 34 bases while playing third base “brilliantly,” in the words of The Sporting News.4

Praised as having all the “making[s] of another great third sacker” for the Pittsburgh Pirates, Gustine celebrated his 19th birthday with an invitation to the team’s spring training in San Bernardino, California.5 Gustine impressed his hero Traynor with his athleticism; but the future Hall of Famer already had an established third baseman, Lee Handley, who was just 25 years old. Consequently, Gustine was assigned to the Gadsden (Alabama) Pilots of the Class B Southeastern League. Big, strong, and about the same size as Traynor, the 6-foot-tall, 170-pound Gustine held his own against considerably older competition, improving his batting average to .300 and demonstrating his superior arm from the hot corner. He was named to the league’s all-star team.

Gustine made an unusually big jump from Class B to the major leagues in September 1939 when the Pirates tabbed him to replace the injured Handley. He debuted at third base in a doubleheader against the New York Giants on September 13 at Forbes Field, where he connected for a single in seven at-bats. Though Gustine hit only .186 (13-for-70) in his trial, The Sporting News noted that he “did a few fancy tricks around the hot corner.”6

Most sportswriters thought that Gustine was still one or two years away from being major-league ready, but when he arrived at the Pirates’ spring training in 1940, new manager and former All-Star second baseman Frankie Frisch tutored him in the art of fielding at the position. By the sixth game of the season, Gustine had replaced veteran Pep Young at second base. Sportswriters had a field day with the 20-year-old Gustine, whom they often described as a “boy,”7 or “cherubic faced,”8 and jokingly made references to him not yet needing to shave. Fans loved him because of his youthful energy and competitive approach to the game. The name “Frankie” even seemed to suggest an adolescent-like exuberance and enthusiasm. In the course of his career, teammates also called him Gus.

Gustine’s bat was red-hot to start the 1940 season. By the end of June he owned a .326 average. Pirates beat writer Charles J. Doyle wrote gushingly that Gustine was “playing a Johnny Evers engagement around the bag.” Doyle was effusive in his praise of the youngster: “His judgment in playing hitters smacks of a [Billy] Herman, and his snap throws and sure hands make him a standout in the art of starting and pivoting double-play numbers.”9 Gustine continued to bat well over .300 through mid-August but suffered a sprained ankle and was hobbled the final six weeks of the season, finishing with a .281 average accompanied by a career-high 32 doubles. Noted for his “smoothness and finish” in the field, Gustine was named the second baseman on The Sporting News All-Rookie team.10 Sportswriters coined the term “pulling a Gustine” to refer to players who experienced unexpected success jumping from the lower-level minors to the big leagues.11

Sportswriter John Drebinger of the New York Times caused a stir in 1941 when he called Gustine the best second baseman in baseball.12 Gustine was a classic contact hitter with an orthodox swing, and was acknowledged as a good bunter with excellent speed. But throughout the ’41 season he battled a number of injuries that limited his effectiveness at the plate and in the field. A tricky grounder from the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Dixie Walker split his right index finger on July 27. Gustine missed two weeks, but the finger and a twisted ankle suffered in August bothered him for the remainder of the season. In spite of the injuries, Gustine was described as a pronounced star around the middle of the infield who had the rare quality of making other infielders play better, especially rookie Alf Anderson, who filled in at times for injured shortstop Arky Vaughan.13 When Handley’s season prematurely ended due to injury, Gustine belted two triples in his first full game playing third base on September 12. He batted .333 (36-for-108) in his last 30 games to finish the season with a respectable .270 average for the fourth-place Pirates.

Frisch considered Gustine a selfless team player whose all-out hustling was in the mold of his own St Louis Cardinals Gas House Gang clubs a decade earlier. Gustine respected Frisch’s desire to win. “He’s a wonder and lashes a whip,” Gustine said of the Fordham Flash, who didn’t take lightly to losing.14 Gustine’s son Bob added, “Our father would come home after a tough loss and tell us how Frisch made all the players just sit on the stools in front of their lockers with their heads down. No one was allowed to talk while Frisch reminded them of all their mistakes. He liked Frisch, but he also said that Frisch made the players feel miserable.”15

The world of baseball changed after the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Heeding the call to duty, many players and coaches enlisted while others were drafted in the ensuing years, depleting big-league rosters. In the offseason Gustine attempted to enlist in the Navy, but was classified as 1-B (available, but fit for only limited duty) and eventually 4-F because of a diagnosed hernia. The 1942 season proved to be frustrating for both the Pirates and Gustine. While rumors of Gustine’s impended draft into the Army circulated in the press, the second baseman slumped at the plate, batting just .229 for the fifth-place Bucs. Gustine’s draft status was a constant topic throughout the war years; his hernia, however, bothered him for the remainder of his playing days.

In many ways Gustine’s scrappy determination, willingness to play through injuries, and winning attitude symbolized Pittsburgh, a gritty industrial city and the world’s leading producer of steel and glass. And in no season was that more apparent than 1943. With players lost to injury and the war effort, Frisch counted on Gustine’s versatility to provide him flexibility with his infield. For the first time in his big-league career, Gustine was moved to shortstop because of his superior arm. He juggled duties at shortstop (68 games) and second base (40 games) throughout the season. In late April he fractured the middle finger on his right hand fielding a grounder.16 Although the injury affected his throwing accuracy the entire season, Gustine went on a hitting tear in June, cranking out 23 hits in 48 at-bats (.479) over a ten-game span from June 6 to 16, including three games with four hits. “Gustine’s consistent hitting, base running, and general heads-up play is one of the bright spots” in Pittsburgh, announced The Sporting News.17 On August 15 he suffered a serious knee injury when his “left leg folded” as he attempted to steal third base. He resumed play in the field only in late September, and was limited to just 112 games that season. Charles J. Doyle writing for The Sporting News captured Gustine’s essence as a player: “Gustine stood out as a symbol of this great team play. … Scorning physical ills, [he] moved back and forth from second to short at the call of his manager. Not once did he say that his broken finger was bothering him or that he should have rested.”18

During the offseason, Gustine lived in Chicago with his parents. He kept in shape by working out at the University of Chicago, and held various jobs, including serving as a deputy clerk in a Chicago court. With his short brown hair, blue eyes, and soft-spoken air, Gustine was an eligible bachelor. His life changed when he met Mary Alice Gormley, a native Pittsburgher who lived just blocks away from Forbes Field. They married on November 25, 1944, at St. Paul’s Cathedral in Pittsburgh. Teammate Jim Russell was his best man. Frankie and Mary Alice Gustine had five children (Frank Jr., Joanne, Robert, Mark, and Mary Louise) and adopted Pittsburgh as their hometown. Their sons recalled how their father was an approachable player, always willing to sign autographs for kids and take the time to talk to people on the streets. Gustine became close friends with not only Traynor but also Honus Wagner (later serving as a pallbearer for both) and players like Russell and Vaughan. According to his sons, Gustine often told a comical story about how Wagner constantly tried to set him up with his daughter.

A notoriously streaky hitter, Gustine struggled at the plate for much of 1944, batting under .200 as late as August 18. A surge in the final third of the season (.301 in his last 47 games) pushed his average to a season ending .230. Despite his offensive inconsistencies, Gustine sacrificed personal accolades by playing out of position at shortstop and remained the infield leader of what Charles J. Doyle called the “strongest part of the club” that finished a surprisingly strong second.19

Playing shortstop primarily but also seeing action at second base for the third consecutive season in 1945, Gustine finally put together an offensively consistent campaign, keeping his average around .280 the entire year. On May 24 against the Boston Braves at Forbes Field, he experienced arguably his strangest game as a big leaguer. When Frisch had used all three of his catchers by the end of the ninth inning with the game tied, 7-7, Gustine donned the tools of ignorance for the final two innings. With two outs and the bases loaded in the top of the 11th inning, Braves center fielder Carden Gillenwater attempted to steal home just as Pirates rookie pitcher Ken Gables unloaded a pitch low and away. In the words of Charles J. Doyle, “Gustine was able to nail it and dive head-first into the speedboy to thwart the winning run.”20 The Pirates’ Johnny Barrett ended the game a few minutes later with a walk-off home run.

For the first time in his career, Gustine was a contract holdout in 1946, signing just two weeks before the start of the season for a reported $9,000 and an additional $1,000 “if he plays regularly.”21 Gustine moved back to second base with the return of sure-armed Billy Cox from the military. In great health, Gustine got off to another fast start, boasting a .338 average on June 15 courtesy of a 16-game hitting streak (tied for the longest in the NL that season). He was rewarded by being named to the NL All-Star squad as a backup to starter Red Schoendienst. He struck out and drew a walk in his two plate appearances in the AL’s convincing 12-0 victory. In an almost annual tradition, Gustine struggled down the stretch. He lacerated his foot on August 11 when teammate Russell inadvertently spiked him. An infection ensued and it became difficult to put pressure on the foot. Gustine played through the pain, but batted just .175 thereafter to finish with a .259 average.

An era came to a close during the 1946 season as the Dreyfuss family, owners of the Pirates since 1900, sold the team to a group led by Indianapolis banker Frank McKinney, and the new ownership made substantial changes in 1947. First-year manager Billy Herman moved Gustine to third base. To accommodate the pull-hitting slugger Hank Greenberg, acquired in the offseason, the dimensions of left and left center field in Forbes Field were reduced, resulting in an offensive explosion. (The Pirates belted a team-record 156 home runs, shattering their previous high of 86 in 1930.) Known throughout his career as a spring hitter, Gustine got off to another torrid start. In July he put together a career-best 21-game hitting streak (39-for-85, .459) to push his average to .335. In the first year fans voted for All-Star Game participants, Gustine came in a close second in the third-base voting to eventual MVP Bob Elliott of the Boston Braves. (Gustine went 0-for-2 in the game.) He cooled off on August, but finished his most successful season by leading the NL in games (156), and setting career highs in runs (102), hits (183), and average (.297).

“You won’t find two finer fellows in baseball than Greenberg and Gustine,” Jackie Robinson told The Sporting News during his second month in the major leagues after breaking the color barrier in 1947.22 Gustine and Robinson first came into contact with each other in 1946 during a segregated barnstorming tour;23 however, Robinson’s compliment probably stems from a game on May 17 at Forbes Field during which he was hit on the arm by an inside pitch from Fritz Ostermueller in the first inning. Gustine reached first base on a walk in the bottom half of the frame and told Robinson, “I’m sure he didn’t mean it.”24 The events were widely circulated in an article by Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier (an African-American paper) the following day. Director Brian Helgeland took liberty with this event in his Hollywood film 42 (2013) by portraying Robinson as getting beaned in the temple by a malicious Ostermueller.

Praised as “the best third sacker in the league” in the first four months of 1947, Gustine underwent a double hernia operation in the offseason.25 “Every year in the last months of the season, I’d get that tired feeling,” said Gustine whose stellar play earned a hefty salary increase to a reported $15,000 in 1948.26 As if on cue, Gustine rapped 50 hits in his first 30 games to pace the NL in hitting with a .427 mark on May 25. Seemingly at the top of his game, he was voted to his third consecutive All-Star Game. “There hasn’t been a more popular Pirate since Traynor,” wrote Bucs beat reporter Les Biederman. “No one can remember when fans at Forbes Field – or any other park – booed him.”27 But Gustine’s second half was as frustrating as his first half was promising. He batted under .200 after the All-Star Game and ultimately lost his starting position in September. With trade rumors intensifying during his slump, Gustine’s tenure in Pittsburgh came to a close when he and pitcher Cal McLish were sent to the Chicago Cubs on December 8 for pitcher Cliff Chambers and catcher Clyde McCullough.

Only 29 years old, Gustine seemingly had several more years of baseball ahead of him, but his career came to an unexpected early end. Like many players before him, he spent his twilight days on an undignified baseball odyssey. Gustine struggled with the Cubs in 1949 (batting .226), was optioned to the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League, and ultimately was placed on waivers. The Philadelphia Athletics claimed him on September 14, but then traded him three months later in a multi-player deal to the St. Louis Browns. In a gesture of good will, the Browns kept Gustine on their roster long enough in 1950 for him to earn status as a ten-year man for his baseball pension.28 On May 22 Gustine was unconditionally released.

The Associated Press reported in 1950 that Gustine had been diagnosed with “nervous fatigue.”29 A noted workaholic, Gustine had little time in the offseason to recover physically from his annual injuries. In 1947 he became the head basketball coach at Waynesburg College, located about 50 miles south of Pittsburgh. He commuted daily from the October until the beginning of spring training, before resigning in 1950 for health reasons.

Gustine remained a popular fixture in Pittsburgh for three decades after his retirement. In 1952 he opened Frankie Gustine’s Restaurant and Bar just blocks from Forbes Field. Decorated with Pirates memorabilia, the establishment, which billed itself as a “Major League Atmosphere with Minor League Prices,” was in business until 1982 and became a hangout for Pirates players in the 1950s and 1960s before Three Rivers Stadium opened in 1970. A successful real-estate developer, Gustine was later part owner of the Sheraton Inn at Station Square, located in one of the most popular tourist areas in Pittsburgh.

Second only to Gustine’s passion for baseball was his love of basketball. He turned down an offer to play professional basketball for the Pittsburgh Raiders in the National Basketball League (a forerunner to the NBA) in 1944, but played informally against high-school and semipro teams throughout his baseball career, much to the chagrin of manager Frisch. According to his sons, in retirement Gustine found a like-minded fanatic in Pirates shortstop Dick Groat, a former All-American basketball player at Duke. “Our father would come home and tell us that he and Groat scored 50 against some high-school team. Then he’d say that Groat had 44,” his son Frank said jokingly. In 1962 Gustine was lured back to the hardwood when he became head basketball coach for Point Park College in Pittsburgh. He resigned in 1967 in order to establish the school’s baseball program. Beginning with a limited fall schedule in 1967 and continuing through spring 1974, Gustine laid the foundations for one of the most successful programs in the NAIA. He led the Pioneers to a 103-46 record, including two district championship and a fourth-place finish in the 1974 NAIA World Series.30

Gustine was in Davenport, Iowa, to take part in the maiden voyage of a riverboat casino owned by his business partner John E. Connelly, when he died of a heart attack on April 1, 1991. He was 71 years old. Services were held at St. Margaret of Scotland Parish in Green Tree and Gustine was buried at Resurrection Cemetery in Coraopolis, Pennsylvania. Gustine’s 12 years in the big leagues and his lifelong service to and interest in sports may best be summed up by a remark from his mentor Pie Traynor from the late 1940s: “I consider Gustine one of the best team men and hustlers in the game.”31

This biography originally appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Newspapers

Pittsburgh Post Gazette

The Sporting News

Websites

Ancestry.com

BaseballAlmanac.com

BaseballCube.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

SABR.org

Interviews

The author expresses his sincere gratitude to Frankie Gustine’s sons, Frank Gustine, Jr. and Robert Gustine, whom he interviewed in August 2013. They provided many insights to their father’s playing career and personality, and helped ensure the factual accuracy of this biography.

Notes

1 The Sporting News, November 11, 1947, 11.

2 Ibid.

3 The Sporting News, June 27, 1940.

4 The Sporting News, March 16, 1939, 2.

5 The Sporting News, January 26, 1939, 7.

6 The Sporting News, December 21, 1939, 5.

7 The Sporting News, February 14, 1940, 10.

8 The Sporting News June 27, 1940, 3.

9 The Sporting News, June 13, 1940, 5.

10 The Sporting News, October 17, 1940, 5.

11 The Sporting News, August 29, 1940, 14.

12 The Sporting News, May 29, 1941, 2.

13 The Sporting News, July 10, 1941, 3.

14 The Sporting News, December 11, 1941, 12.

15 Interview with Frankie Gustine’s sons, Frank Gustine and Robert Gustine, in August 2013. All quotations from them are from these interviews.

16 The Sporting News, April 22, 1943, 10.

17 The Sporting News, June 17, 1943, 5.

18 The Sporting News, July 22, 1943, 2.

19 The Sporting News, September 13, 1944, 4.

20 The Sporting News, May 31, 1945, 9.

21 The Sporting News, April 4, 1946, 15.

22 The Sporting News, May 28, 1947, 9.

23 Thomas Barthel, Baseball Barnstorming and Exhibition Games, 1901-1962 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007), 221.

24 Jonathan Eig, Opening Day. The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2008), 140.

25 The Sporting News, November 12, 1947, 10.

26 Ibid.; The Sporting News, February, 4, 1948, 10.

27 The Sporting News, May 12, 1948, 17.

28 “Teams Down to 25-Limit” (UP), Bend (Oregon) Bulletin, May 14, 1950, 9.

29 “Training Camp News” (AP), Ludington (Michigan) Daily News, April 4, 1950, 8.

30 Point Park University Athletics. pointpark.edu/Athletics/MensSports/Baseball/BaseballNews2012/media/Athletics/Baseball/naiaopeningrdinfopacket.pdf

31 The Sporting News, December 15, 1948, 3.

Full Name

Frank William Gustine

Born

February 20, 1920 at Hoopeston, IL (USA)

Died

April 1, 1991 at Davenport, IA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.