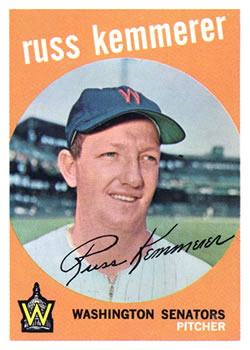

Russ Kemmerer

Russ Kemmerer pitched a one-hit shutout in his first major-league start, on July 18, 1954, at Fenway Park, leading the Boston Red Sox to a 4-0 win over the Baltimore Orioles. Deprived of a no-hitter in the seventh inning when Sam Mele’s fly ball to left field eluded the outstretched glove of Ted Williams, the 22-year-old rookie recalled how elated he was when Williams approached him in the locker room after the game and said, “Great job kid, a hell of a great job.”

Russ Kemmerer pitched a one-hit shutout in his first major-league start, on July 18, 1954, at Fenway Park, leading the Boston Red Sox to a 4-0 win over the Baltimore Orioles. Deprived of a no-hitter in the seventh inning when Sam Mele’s fly ball to left field eluded the outstretched glove of Ted Williams, the 22-year-old rookie recalled how elated he was when Williams approached him in the locker room after the game and said, “Great job kid, a hell of a great job.”

Ted was Kemmerer’s boyhood idol; the two first met in June 1949 when the Red Sox and Pirates played an exhibition at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. Russ was a senior at Peabody High School in Pittsburgh and was being scouted by several big-league clubs, with the Red Sox one of the interested teams. Invited to pitch pregame batting practice, the prospect threw to the reserves and a few of the regulars, and then Williams approached the plate. The Splendid Splinter sensed the youngster’s nervousness, and told him, “Hey kid, just get it over the plate.”

That phrase was used in the title of a 2002 book, Ted Williams: “Hey kid, just get it over the plate!”, co-authored by Kemmerer and W.C. Madden. The book chronicles the life of Russell Paul Kemmerer from boyhood to major-league ballplayer, husband, father, clergyman, coach, and educator.

The fifth and last child born to Frederick and Therese May (Skidmore) Kemmerer, Russell arrived on November 1, 1931, in Pittsburgh. Other siblings in the household (Fred, Nevin, Katherine, and Mary Lou) were much older; Russ followed Mary Lou, the next youngest, by 11 years. Of German heritage, the Kemmerers were successful in providing a loving home for their brood. Frederick, small in stature, was employed for 42 years by Union Switch and Signal, a manufacturer of switches for railroad crossings. The parents’ faith in God led the family to Emory Methodist Church on a regular basis.

Young Russell was active in football, basketball, and baseball at Kingsley House, a neighborhood center, and the Emory Methodist softball roster included the senior Kemmerer as team manager and the sons as players. At Peabody High School, Russ earned varsity letters in volleyball, football, basketball, and baseball. He quarterbacked the football squad, led Pittsburgh prep basketball players in scoring his senior year, was the ace pitcher on the baseball nine, and was named to all-city teams in each sport.

College recruiters noted the youngster’s exploits on the gridiron, hardwood, and diamond, and professional scouts followed his progress in the area’s semipro baseball leagues. After high-school graduation, the Kemmerer family decided that it was best for Russ to accept the full athletic scholarship offered by the University of Pittsburgh, where they could watch him compete. Freshmen were not permitted to play football, but he saw action on the frosh basketball and baseball teams. When the spring term ended, Kemmerer was again pitching semipro ball, and Red Sox scout Caleb “Socko” McCarey came calling with a $3,000 signing bonus and a single-A contract to Scranton. The offer overwhelmed the modest Kemmerer household and the 6-foot, 2-inch, 198-pound right-hander became Boston property in June 1950.

Rather than report to Scranton for the remainder of the summer, the club agreed to let Russ remain at home and pitch for Dormont in the Greater Pittsburgh League, recognized as the top semipro circuit in the area. Several future major leaguers played in the loop, including Bob and Ed Sadowski, Frank Thomas, Bob Purkey, and George Susce Jr. After the close of the semipro season, he took another big step in life when he married a hometown girl, Betty Hasley.

Kemmerer played five games for Scranton in 1951; he was sent there at the start of the season, but the pitching staff was overloaded and he spent the rest of his rookie season in Roanoke in the Class B Piedmont League, where he pitched in 35 games, compiled a 6-11 won-loss record and an ERA of 4.69. He returned home to celebrate his 20th birthday in November, as well as the arrival of his first son, Rusty. As 1952 approached, the Red Sox requested that he report in January to Sarasota, Florida, for a special training session with other top minor-league prospects. The club had named Lou Boudreau as its new manager, and wanted him to evaluate its prize recruits.

Russ remained for further training with the big club in the regular spring camp, and worked in several games before joining the Triple-A Louisville Colonels at Deland, Florida. His work there earned him a roster spot, but he found the jump from Class B to Triple-A was no easy task. Hurling in 25 games for the fifth-place Colonels, he won seven, lost eight, and posted a 5.43 ERA.

The Red Sox invited Russ back to Sarasota in 1953; he pitched well and made the trip north to Boston, but was optioned to Louisville three days before the Red Sox season opener. He notched 11 victories against 8 defeats with the Colonels and lowered his ERA to 3.40. In 34 games, he went the route nine times, hurled 188 innings, pitched a pair of one-hitters, and was the victim of several one-run losses.

In 1954 Kemmerer was one of a few rotation candidates to have options left, and he returned to Louisville to open the season. In response to the demotion, he dazzled on the mound with a sparkling ERA of 2.08 in 14 games, and despite a 5-6 record, was recalled by the big club in mid-June. Kemmerer made his major-league debut on June 27 in a relief role against the White Sox at Comiskey Park. With two men aboard and one out in the fifth inning, he pitched to George Kell, who promptly doubled to left field, driving home both runners. After walking Sherm Lollar, he retired Jim Rivera on a pop-up and Johnny Groth on a strikeout. Kemmerer completed his inaugural day with a scoreless sixth inning.

The rookie was used in four other mop-up roles prior to the one-hitter on July 18, a performance that was followed by eight more starts. Overall, Kemmerer finished his first year in the big leagues with 5 wins, 3 losses, and a 3.82 ERA. The Red Sox sent him to the Puerto Rican Winter League in October 1954 to sharpen his curve and changeup; he won nine games there before returning home in January 1955 with an injury to his right shoulder. After treatment, he went to spring training and made the Opening Day roster, but was shipped back to Louisville after appearing in seven games with a 1-1 record. Kemmerer fared poorly on his return to the American Association; he won only three times and suffered eight defeats, with a 4.96 ERA. There was one bright spot that summer, however; Betty Kemmerer gave birth to a daughter, Cheryl, on July 18.

Boston used its final option on Russ during spring training in 1956 when they dispatched the right-hander to the San Francisco Seals, a Pacific Coast League club that had replaced Louisville as the top Red Sox farm club. Kemmerer pitched 13 complete games, had a 3.48 ERA, and was 12-14 for a weak-hitting team. He rejoined the parent club in the spring of 1957 and was used sparingly in training games, but remained with the team through the first two weeks of the regular season. He made only one relief appearance, pitching four innings in a 7-5 Baltimore victory on April 22. Tom Brewer, Frank Sullivan, Ike Delock, Willard Nixon, and Dave Sisler were carrying the pitching load, and Russ became expendable. On April 29 he was traded, along with infielder Milt Bolling and outfielder Faye Throneberry, to the Washington Senators for pitchers Bob Chakales and Dean Stone. The brief career in a Boston uniform was over; in three partial seasons he had totaled 96⅔ innings in 27 games, with 11 starts, 6 victories, 4 defeats, and an ERA of 4.47.

Kemmerer spent the equivalent of three full seasons with the Senators, a perennial last-place finisher. The positive aspect about the trade was the opportunity to be a starter on a regular basis. From May 3, 1957, through May 5, 1960, he pitched in 119 games, with 87 starts, 20 complete games, and 620 innings pitched. His won-loss record was understandable for a cellar-dwelling club: 21-45, with a composite ERA of 4.76.When Kemmerer arrived in 1957, the pitching rotation at Washington was primarily Pedro Ramos, Camilo Pascual, and Chuck Stobbs. The newcomer lessened their load; he made 26 starts, won 7 games and lost 11. Kemmerer’s bat produced a .067 (3-for-45) average, but he knocked in six runs with a double and the only two round-trippers of his major-league career. Asked about his strengths as a pitcher, Kemmerer said, “The fastball was my primary pitch, and modern guns would probably have measured my best at 94-95 MPH. I also had a good breaking ball and used a forkball, now called the split-finger, as my changeup.”

In 1958, Kemmerer won only 6 decisions and dropped 15, but one of the defeats was the result of being on the wrong side of a one-hitter by White Sox left-hander Billy Pierce. He also lost 2-1 and 2-0 decisions to Baltimore. Russ won eight games and dropped 17 in 1959 with a 4.50 ERA over 201 innings for the hapless Senators who lost 91. Kemmerer’s 17 losses were second most in the American League. Teammate Pedro Ramos, who had 19 losses, saved Russ from being first in a rather inglorious category. One of Kemmerer’s strengths was in his control. In almost every year he pitched, he struck out more batters than he walked.

After losing two of three starts for the Senators in 1960, Kemmerer was sold to the White Sox on May 18 for a reported $30,000. Chicago was the defending AL champion and skipper Al Lopez planned to use the new acquisition as a swingman. In that role he appeared in 36 games, seven as a starter, and went the distance in a 2-0, three-hit victory over Kansas City on June 5. His overall record was 6-3, with two saves and a 2.98 ERA, a career low. Chicago’s strength up the middle, with catcher Sherm Lollar, middle infielders Luis Aparicio and Nellie Fox, and center fielder Jim Landis, was a major improvement over Washington’s defenders. The White Sox finished 20 games over .500 (87-67), but trailed the pennant-winning Yankees by 10 games.

The Kemmerer family had moved to Bloomington, Illinois, when Russ was sold to the White Sox, and under the guidance of Dr. Merrill Smith of the local Methodist church, the big right-hander began to prepare for a new vocation: the ministry. He took courses at nearby Wesleyan University, and served the church by working in youth programs and visiting nursing homes and shut-ins.

The Maris-Mantle battle to break The Babe’s single-season home run record sparked the 1961 season, and Kemmerer contributed to the drama by surrendering a pair of Maris’s round-trippers. For the season, he broke even with 3 wins and 3 losses, worked in 47 games, started only twice, and his ERA soared to 4.38 as Chicago dropped to fourth place.

Kemmerer reported to the White Sox spring-training base in 1962 with a sprained ankle and when the season began, he was relegated exclusively to relief duty. On June 25, having pitched just 28 innings in 20 games, he was traded to the Houston Colt .45s, one of the two expansion teams in the National League. Chicago acquired left-handed pitcher Dean Stone in the transaction; it was the second time in their careers that the two hurlers were exchanged for each other.

Kemmerer had hoped to move into a starter’s role with Houston; he did make two starts and lost both, but had success in 34 relief appearances. Over 59 innings he recorded five wins, a single loss, and three saves. In the new 10-team format the Colt .45s managed to win 64 games and salvage eighth place, finishing in front of the Chicago Cubs and the 120-loss season of the hapless New York Mets.

Houston’s pitching improved in 1963, and the veteran Kemmerer, with the end of his big-league career in sight, worked in only 17 games before his release in June. He threw 36⅔ innings, recorded one save, and had no wins or losses. His final appearances with the Colts were on June 23 at Cincinnati, where he relieved in both games of a doubleheader, hurling five innings and giving up a two-run homer to Jesse Gonder. The Colts retained Kemmerer’s services, however, when they signed him as the pitching coach for the Triple-A team at Oklahoma City.

Involved in a tight Pacific Coast League pennant race, manager Grady Hatton put his pitching coach and former Red Sox teammate on the active roster, and Russ answered the call; he won five of eight decisions and recorded a 2.80 ERA in 74 innings as the 89ers won the Southern Division flag by a half-game over San Diego. And in the playoffs, Hatton’s crew triumphed over Northern Division champion Spokane, four games to three. Kemmerer’s contribution to the PCL title was a 9-0 shutout in Game Six.

After one more season with Oklahoma City, hurling mostly in relief, Russ called it a career; he finished in 1964 with 8 wins, 6 losses, and a 2.70 ERA. In the final month with Oklahoma City, he visited with former Red Sox third baseman Ernie Andres, the baseball coach at Indiana University, who presented him with a career-change proposition: become the pitching coach for Andres, take classes at the university to earn a degree, and be involved in a working capacity with the Methodist Church. Russ agreed, and in the fall of 1964 the family moved to Monrovia, Indiana, where he took over as pastor of two small churches, worked with Indiana’s baseball program, and attended classes on campus over a prolonged period of time, while he worked and attended to his ailing wife.

Prior to graduating in 1977 with a degree in parks and recreation, Russ took a job in Seymour, Indiana, as the city’s parks and recreation director. He supervised the youth and adult programs at the two public park facilities as well as ministering with the United Church of Christ. There were two parks in Seymour, both with adult and youth programs. Kemmerer stayed on there for seven years. Having worked with and counseled young people over the years, Kemmerer yearned to coach and teach full time, so he returned to Indiana University and in 1981 he earned a second sheepskin, this one in secondary education, with an emphasis on English. (He followed up by receiving a master’s degree in 1982.) He took his teaching credential to Milan, Indiana, where for two years he was employed as the high-school football coach and a junior-high English teacher.

Baseball was still Russ’s passion, though, so he applied for and was accepted in 1980 for the positions of head baseball coach, assistant football coach, and English teacher at Lawrence Central High School, one of three high schools in Lawrence Township, on the east side of Indianapolis. Russ Kemmerer had finally won a permanent spot in the rotation. He stayed on as a member of the faculty at Lawrence Central for 21 years, where he shared the success of his students on the playing field and in the classroom. According to the coach-teacher, his students gave him a nickname of respect and love: “Special K.”

A sad note in 1986 was the death of Russ’s wife, Betty. After mothering the four Kemmerer offspring (Russell, Darrell, Cheryl, and Kimberly) through the varied career travails of her husband, Betty Kemmerer passed away from ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease). Two years later, Russ was blessed when he met and married his second wife, Susannah.

Kemmerer’s nine years in the major leagues produced a won-lost record of 43-59, with an ERA of 4.46. He pitched in 302 games, worked 1,066⅔ innings, gave up 1,144 hits and 389 walks, and struck out 505 batters. In relief he won 18, lost 7, and totaled 8 saves.

In retirement, Russ was a participant in golf tournaments with former teammates and competitors, and enjoyed visits to the Ted Williams Museum in Florida, And, according to Russ, his occasional appearances as a baseball history spokesman in literature classes at DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana, were well received. (The course is called “Baseball History and Literature.”) He also served as a coach in the football and baseball programs at Christian Heritage High School in Indianapolis until Susannah Kemmerer retired in 2009. Also in 2009, one of the outstanding individual performances in Indianapolis high school competition was recorded by freshman softball pitcher Leah Kemmerer, who threw five no-hit games during the season. Proud grandfather Russ was hopeful Leah would continue to be successful in her hurling career. As pf 2014 Russ and Susannah Kemmerer divided time between their residence in Indianapolis and a vacation home in Clearwater, Florida.

Russ Kemmerer, 83, passed away on December 8, 2014, in Indianapolis.

Sources

Russ Kemmerer, Ted Williams: “Hey kid, just get it over the plate!” (Indianapolis, Indiana: Madden Publishing, 2002).

Russ Kemmerer, telephone interviews, August 6 and 13, September 18, and October 7, 2009.

Raymond J. Nemec.

Full Name

Russell Paul Kemmerer

Born

November 1, 1930 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

Died

December 8, 2014 at Indianapolis, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.