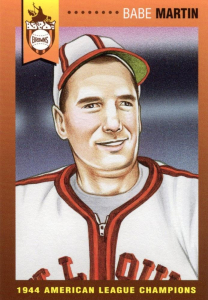

Babe Martin

Babe Martin was born Boris Michael Martinovich, the son of a professional wrestler, Iron Mike Martin (a/k/a Bryan Martinovich). Both of Boris’ parents — Mitar and Vidosava Martinovich — were born in parts of the former Yugoslavia, his father in Montenegro and his mother in Serbia. They each emigrated to the United States and settled in Seattle in the Pacific Northwest. At least one geographically-challenged sportswriter once dubbed him the “Hungarian hot-shot.”

When wresting, the senior Martinovich adapted his surname to the circumstances. He wrestled in Montana and he wrestled in Chicago, and in any number of other places. If he was wrestling in an Italian area, he took the name Martini. In a Scottish or Irish area, he became McMartin or O’Martin. “Dad could speak a number of European languages, being born over there,” Babe said, adding “When he married mother, that was the end of his wrestling.”

Boris had two brothers and two sisters, Lola and Olga. Brother Robert was the only other one interested in sports, but it wasn’t something he pursued past college. He became part-owner of a Budweiser distributorship in Florida, while brother Bryan — who’d boxed and wrestled a bit professionally before going into the service — became a jeweler in St. Louis. Boris married the former Mildred Slapcevich of St. Louis in 1943. He never legally changed his last name, but generally went by the name Martin. His sons, though, prefer to stick with Martinovich.

His mother prompted a family move to Zeigler, Illinois, in the southern part of the state, due to a conflict with an in-law. Born on March 28, 1920, Boris was just one year old at the time of the move. “The only type of industry at that time in southern Illinois was coal mining so my dad went to work in the coal mining business. A shaft caved in on him. He survived that, but died about three years later. He just died. Back in 1926, they didn’t know how or what a person died from.” Boris was three at the time of the accident, and the family moved on to St. Louis.

Boris’s mother was very supportive of his ambitions when Boris showed athletic inclinations early on. “I played on sandlots, glass, and gravel fields, under bridges, wherever I could go ahead and play on. Playgrounds, wherever, you know. In the summertime, I’d be gone early in the morning and come home at dusk”. Martin was a good ballplayer, good enough that “they took me out of grammar school, seventh grade, to play on the ninth-grade high school team.”

As the youngest in his family, he was called Baby. “They called me Baby for years. And then as I got a little bit older, it got to be a little bit embarrassing so they called me Babe.” He was Babe all through high school and beyond.

Though he was both a catcher and outfielder in pro ball — and only a catcher during his brief time with Boston in the majors, he began as an infielder. “As I grew, I got larger. If it had been today, I never would have consented to be a catcher. I could play first base. I was a pretty good infielder; although I was big, I could have moved to third base. But you know, back then, you did what you were told. If they wanted you in the outfield, you moved to the outfield. Today they don’t take that….”

Martin played for McKinley High School in St. Louis in 1936-38, and his high school coach was Lou Maguolo, who scouted in the area for the St. Louis Browns. Maguolo later retired from coaching and became a full-time scout, working in that capacity for the New York Yankees. Babe was all-district in basketball and also played three years on the school’s football team.

Martin graduated from high school in 1940 at age 20 and most sources show him as signing with the Browns then. “Actually,” Martin confides, “I signed in high school unbeknownst to anybody. I signed in 1938. They gave me a job working in the Browns office at $100 a month and I worked out with the Browns and Cardinals. Back in the ’30s, I guess ’37, ’38, ’39, we didn’t have any money. So $100 a month, bringing that home for my mother…my brother Bryan was really the only one that was working at the time. I was working in the office…office work. Answering the telephone at the switchboard. I wasn’t very good at that, but mostly I was on the field. I was working out.”

He kept active until he graduated from McKinley, when his signing was announced and he was sent to play ball in Palestine in the East Texas League. The franchise “blew up” and relocated in Tyler, where for the first time he began to play games behind the plate.

It was at Tyler that he was beaned by a pitcher named Bob Crow. “I was in the hospital for about seven days. He told me it was an accident. When I got out, they thought it was better for me if I didn’t have to face pitchers in the East Texas League. I guess they figured maybe I would be afraid to get up there. We didn’t have helmets or anything.” Martin had secured a hit off Crow his first time up. Next time, he took a fastball right above the left eye. Martin had been hitting .274 at the time. He was sent to another Class C team, St. Joseph in the Michigan State League, to finish out the year. When he got there, he learned that Crow had bragged that he “showed that rookie so-and-so not to get a base hit off me. To be honest with you, I looked for Bob Crow for a number of years after that, trying to go ahead and find that…because he said he intentionally hit me. You know, if you intentionally hit a guy in the head, you’ve got to answer for that with your hands, you know. And I was pretty good with my hands.” He never found Crow, and that might have been fortunate for the pitcher. Martin hit .235 the rest of the year. As late as August 1944, writer Don Wolfe said that Babe still suffered head pains.

In 1941, Martin had a terrific year, catching and playing in the Northeast Arkansas ball club in Paragould, Arkansas, hitting .353 to lead the league, with 54 RBIs in 75 games. In 1942, he played in the Three-I League for Springfield, Illinois, at four positions: catcher, outfield, and the two infield corner positions. He batted a very strong .325 with 12 homers and 63 RBIs in 345 at-bats. In September, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy and was stationed at Lambert Naval Air Station right there in St. Louis.

“When I got there, when I was signing up, a chief petty officer saw my résumé and he said that we’re trying to start a baseball team. He said, ‘Would you like to play baseball here at Lambert Field?’ I said, ‘Sure, I’d love to.’ And then he asked me if I knew any other ballplayers that were going in the service, and I said, ‘I sure do.’ ‘Well,’ he said, ‘If they’re about ready to go, tell them to come on out.’ So I was able to get some of the ballplayers who were with the Browns and the Giants and whatever and they came out to Lambert Field. Some of them went to the South Pacific later to play with the major league ballplayers out there. I stayed with Lambert Field, and got hurt playing. I got a ruptured quadricep in my left thigh. We beat Great Lakes in 1943, I think 1-0. Mickey Cochrane was their manager. I think Johnny Mize was playing first base at the time, but we had a pretty good baseball team out at Lambert Field.”

Because of the quad injury, and duodenal ulcers, he spent four months at Great Lakes Naval Hospital before being discharged in April of 1944. His right thigh was said to be three inches shorter in circumference than his left. The Browns fitted him with a brace that he “used all of ’44 and almost all the rest of my career. While I was playing. It was a brace that I had a belt to keep on. I put it on my left thigh from my knee up to my groin.” Martin was also reported to keep a quart of milk in the dugout during ballgames so he could help keep the ulcers under control. Taking care of himself helped do the trick. Martin hit .350 in the American Association, playing for the Toledo Mud Hens, with 14 homers and 72 RBIs. He had five hits in the All-Star game and at year’s end was voted both the MVP of the league and rookie of the year, though he will still say that he believed Johnny Wyrostek more deserving of the MVP award. At the end of the year, he was called up to St. Louis. He was now playing in the same Sportsman’s Park where he’d worked out as a kid. He debuted with a two-for-three game against the visiting Red Sox, and then hit a pinch single his only other time up. He batted .750 — three hits in four at-bats with a run batted in.

And he had a better than front-row seat for the 1944 World Series. All in all, “it was really a great feeling. It was my dream. And I was able to sit on the bench, in uniform, during the World Series, although I was not allowed to open my mouth en route under any circumstances. Those were the orders, if I was to sit on the bench. I saw the whole Series between the Cardinals and the Browns. It was great to watch it.” A couple of years later, he went to every game of the 1946 World Series, as well. Did he root for the hometown team? “I was an American Leaguer, if you remember. I really concealed myself pretty good on that Series.”

In 1945, he had his first true taste of major-league ball, but it was tough to get into a rhythm because of the start-and-stop nature of the work assigned him. The ball club had a big gate attraction in Pete Gray. Martin was completely candid in his remarks: “The Browns brought up a guy by the name of Pete Gray. He was a one-armed ballplayer, and there wasn’t one ballplayer — and I know this is all being taped — but I can tell you that there wasn’t one fellow on the ball club that was happy about Pete being there and playing. Pete played almost every game in center field for the Browns and he took Mike Kreevich’s place. He would take my place. He would take Milt Byrnes’ place. He would take…he was a ticket draw. Pete, God bless him, he couldn’t throw anybody out. It was automatic first-to-third for a runner, but it was like Nelson Potter said (who was a great pitcher for us that year), that cost us…that really cost us the pennant. People would think that’s sour, but that was the feeling at that time. I don’t think any of us were envious. We thought…at least I thought I should be playing. Going in one game and out another game wasn’t the way to go to get yourself started.” Babe got into 54 games, all as an outfielder, and accumulated 185 at-bats, but only an even .200. At the end of July, the Browns added Lou Finney and Martin was sent down to Toledo, where he played for the Mud Hens and hit .300 in nine games.

In 1946, Martin played for the Pacific Coast League’s Oakland Oaks, under manager Casey Stengel. “I tried very hard to go ahead and do a good job for Casey and I wasn’t able to achieve that [.244 in 82 at-bats], so the Browns brought me back and sent me to Toledo, and I finished out the season in Toledo in ’46.” With Toledo, he appeared in 50 games and batted .265. At the tail end of the season, he came back to the Browns, getting into three more games. He had two hits in nine times up.

He had a very good year catching for Toledo in 1947, batting .319, with 15 homers and 64 RBIs, and in November he was taken in the Rule V draft by the Red Sox. Babe spent all of 1948 and 1949 with the Red Sox, but it cost him a great deal of playing time. In 1948, he got just four at-bats all season long and in 1949, he got just two. ”I was the third catcher under Birdie Tebbetts, who was the first catcher, and a young guy by the name of Matt Batts — an excellent catcher. He was the second catcher, and I was the third catcher. I worked very hard to stay there. I really worked very hard. At the end of the ’49 season, [Red Sox GM] Joe Cronin sent me to Louisville. I had a telephone call from Mr. McCarthy — who was our manager, Joe McCarthy — who told me he had nothing to do with me being sent to Louisville. That was Mr. Cronin’s idea. He was the boss.”

Martin split 1950 between Louisville and Toledo. “Louisville sold me to Toledo. The Red Sox…Mr. Cronin didn’t want me for some reason, so they sent me to Toledo.” He was back in the Browns system again. It wasn’t a good year, and he hit only .211, with just 13 RBIs in 152 at-bats.

The next two years were spent in the Texas League, playing for San Antonio. There he played some first base the first year, and caught, batting .261 in 1951 and boosting that to .329 the following year. Although he’d played a large part of his career behind the plate, Martin says he’d never truly been taught the craft — not as unusual in the era as one might think today. And for the first time, he began to play first base. “I think I more or less learned how to really catch in 1952. It took a little while. I had no real instructions on how to catch. I just more or less had to learn by myself, with the exception that the Browns had a great former big league first baseman by the name of Jack Fournier. He was a good one.”

1953 was again spent doing very little, but at least it was doing very little while on a major league roster, this time again with the Browns. He was the third catcher on the staff once more, and as in 1949 was hitless the only two times all season long that he got a chance to bat. In July, he was told to report to the Toronto Maple Leafs but elected to retire instead. Come 1954, “they told me they couldn’t afford to pay me the $5,000 that I was making in ’53 and sent me back to Toledo. That’s when I quit for the season.” He never reported to Toledo and was placed on the disqualified list. The St. Louis Browns still held his contract, though. The franchise moved to Baltimore in the offseason, and as the Browns became the Baltimore Orioles, Martin says, “I was able to secure my release. Mr. Artie Ehlers, who was the first general manager, was kind enough upon my request to give me my release so I could go ahead and get a little bonus and a salary playing with some minor league ball club.” The club was Dallas, and it was Martin’s last year in organized ball.

Babe was back in the Texas League in 1954, and played for Dallas for half a year, batting .262, but then just quit. He had an interest in brother Bryan’s jewelry business and that appealed to him. The owner of the Dallas club wanted him to manage, but “I just told Mr. Burnett, the owner of the ball club, ‘Man, at this age, for me to go ahead and take care of high school kids and drive a bus’ — this is what we did back in those days, the manager drove a bus — ‘No, I don’t want to be a part of that.’ That was the end of it.”

The jewelry business didn’t work out well, and he lost the money he’d invested, in large part because his brother had too many friends and was too generous, selling jewelry at very little over cost — not securing enough of a profit for the business to survive. Babe got a job working for Highway Trailer Corporation out of Edgerton, Wisconsin. He went into the truck/trailer business as a salesperson based in St. Louis. “I did very well in that. To be honest with you, I don’t think I sold a trailer for the first year or two, but after that people knew that we were going to stay in business and that I was going to be their trailer salesperson, I think everything turned out real good. That was the best job I ever had, outside of being a real estate broker, which I later became.

“When I left baseball I wanted to make sure that my children had their college education.” One spring training, umpire Dusty Boggess urged Martin to become one of the men in blue, saying he saw it a sure thing that Martin reach the majors by 1954. “But my wife was a very sick woman, and I had to get home to my children. I was able to send my three children to school, which was the most important thing to me. I’m very proud, they’re all three each very well off with their own businesses and I’m very proud of them.”

What about the 2004 World Series? “My goodness, don’t even ask me. The people who own the St. Louis ball club…Bill DeWitt, the general managing partner, was our batboy back in the ’40s. His son belongs to our 1-2-3 Club. Bill the third. I had a lot of empathy for the Cardinals, but I played with the Red Sox. Dom DiMaggio, Johnny Pesky, Bobby Doerr, Sam Mele, Boo Ferriss…I’m in contact with those guys all the time. Dom DiMaggio treated me like a first-team player. Pesky. Doerr. Ted Williams. Everybody had tremendous respect for one another.

“I’ll tell you something, I was very, very happy for the Red Sox. They needed that, and I’m very happy for them. I would never want to root against the Cardinals. Stan Musial and I are very good friends. Red Schoendienst and I are good friends. I don’t root against the Cardinals on anything, but I’m very happy for the Red Sox. They’re my team, but I love the Cardinals because I’m very close to the owners.

“One thing I regret is that I didn’t stay in baseball to become a major league umpire. I would love to have done that. I’d love to have stayed long enough to have qualified for a pension. I had an opportunity to do that. But I love these guys. We’ve always been friends.”

Martin died on August 1, 2013 in Tucson, Arizona.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Sources

Interview with Babe Martin done March 3, 2006 by Bill Nowlin. All quotations attributed by Martin are from this interview unless otherwise indicated.

Leib, Frederick. “Socking Babe Martin Sacks Up Association’s Most Valuable Title,” The Sporting News, October 26, 1944.

Wolfe, Don. “Babe Martin, Fugitive From Hospital, Builds Up Healthy Bat Mark In Toledo,” Toledo Times, August 1944

Full Name

Boris Michael Martin

Born

March 28, 1920 at Seattle, WA (USA)

Died

August 1, 2013 at Tucson, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.