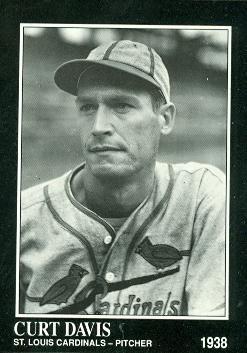

Curt Davis

Curt Davis didn’t make it to the majors until he was 30, although that was his secret. He dodged questions about his age and stuck around until he was almost 43. Davis’s 158 big-league victories are the most by any pitcher who debuted after his 30th birthday.

Curt Davis didn’t make it to the majors until he was 30, although that was his secret. He dodged questions about his age and stuck around until he was almost 43. Davis’s 158 big-league victories are the most by any pitcher who debuted after his 30th birthday.

Like Lefty Grove, Davis was trapped in the minors by baseball’s reserve clause. The San Francisco Seals refused to sell him to a big-league club for four years, long after he appeared ready for promotion.

The lanky sidearm right-hander featured a sinking fastball, a curve, and a palm ball that dropped like a spitter. “Every ball he throws sinks, sails or spins,” catcher Mickey Owen said. “And they do it at the last second.”1 Exceptional control was Davis’s calling card.

Curtis Benton Davis was born in Greenfield, Missouri, on September 7, 1903, the second of five children of William Riley Davis and the former Ida Brown. When Curtis was 3, the family moved to a farm near Salem, Oregon. Farm chores left little time for play. The boy was introduced to baseball when he entered Monmouth High School, where he played first base and the outfield as well as pitcher.

Curtis dropped out of school and found jobs picking apples, laboring on road construction, and working as a lumberjack and truck driver in logging camps. He didn’t have the energy for baseball: “You see, after the kind of work I used to do, a fellow didn’t need much exercise for recreation.”2 As he told it, he was watching a game between rival town teams when he remarked that he could do better than that lousy pitcher. The team’s manager overheard him and called him out to the mound. Lumberjack boots and all, Davis finished the game with six strong innings. He became an itinerant semipro pitcher, jumping from team to team for pay raises from $15 a game to $50.

Davis was 24 years old when he signed his first professional contract with San Francisco of the Pacific Coast League in the fall of 1927. After a year in Class-C ball at Salt Lake City, he and his teammate Lefty Gomez moved up to the Seals in 1929. The 20-year-old Gomez went 18-11, Davis 17-13.

The Yankees paid $45,000 for Gomez, and the Seals hung a similar price tag on Davis. Several major league clubs were interested, but not at that price. Davis stayed in the Coast League for four more years, racking up two 20-win seasons and leading the league with a 2.24 ERA in 1932. The club rejected a reported $25,000 offer from the Giants’ Bill Terry. Davis longed to go to the majors, but baseball rules left him no way out. “I feel those San Francisco owners deprived me of thousands of dollars in salary,” he said.3

The Seals owners paid for their greed when Davis became eligible for the minor league draft after the 1933 season. The Philadelphia Phillies claimed him for just $7,500.

The Phillies spring roster listed the rookie pitcher’s age as 28, not 30. Manager Jimmie Wilson said Davis’s control and easy sidearm delivery reminded him of Grover Cleveland Alexander, whom Wilson had caught.

Forget Alexander; Grover Cleveland could have helped the seventh-place Phils’ pitching staff. Davis quickly became the ace, chalking up a 2.95 ERA while playing home games in the National League’s unfriendliest ballpark for pitchers, Baker Bowl. It was the lowest ERA by a regular Phillies starter in 14 years. Davis finished 19-17 for a club that won only 64 games, and his 51 appearances led the league.

He was almost as effective in 1935 — 16-14, 3.66. Davis did not strike out many; his sinkers made hitters pound the ball into the ground and induced a lot of double plays. He seldom walked a batter. He had established himself as an elite pitcher on a losing team. After the season he married Lillian Preston, whom he had met in Philadelphia.

Davis was traded into a pennant race in May 1936. He was the key man in a swap with the Chicago Cubs that brought right fielder Chuck Klein back to Philadelphia, where he had put up Hall of Fame numbers in Baker Bowl.

It was Davis’s bad luck to play for the Cubs between their pennants of 1935 and 1938. The club finished second in both ’36 and ’37. He joined a strong pitching staff, sliding into the starting rotation with Bill Lee, Larry French, Lon Warneke, and Tex Carleton. Davis was chosen for his first of two All-Star teams in 1936. His 3.00 ERA was the team’s best, and he contributed an 11-9 record.

He came down with a sore shoulder during spring training in 1937 and was practically useless for the first half of the season. After making his first start on July 4, he finished 10-5, but his ERA swelled to 4.08.

Just after Opening Day in 1938, Davis was involved in the biggest trade of the year. The Cubs sent $185,000 and three players to St. Louis for Dizzy Dean. Both teams knew Dean had a sore arm, but the Cubs were willing to bet on a comeback. It didn’t happen. Chicago won the pennant with little help from Dean.

The Cardinals were in transition, breaking in some of the players who would lead their powerhouse team of the 1940s. The 1938 edition came home in sixth place, dragged down by weak pitching. Davis was above average with a 3.63 ERA and 12-8 record. For the first time, he led the league with just 1.4 bases on balls per nine innings.

Davis thought an official scorer robbed him of a no-hitter against the Dodgers on August 24. In the second inning, Brooklyn’s Ernie Koy dragged a bunt to first base. Davis, covering the bag, dropped the throw from Johnny Mize and Koy was safe. Davis believed he should have been charged with an error, but the first-base umpire, George Magerkurth, said Koy had beaten the throw even if Davis had caught it. It was the only Dodger hit.4

The Cardinals jumped into the pennant race in 1939 with the 35-year-old Davis leading the way. He won 22 while losing 16 with a 3.63 ERA in 248 innings. It was his best showing since his rookie year, generously supported by the league’s strongest offense. For good measure, he had his best season at bat, hitting .381 with 17 RBIs. The Cards won 92 games, but couldn’t catch the Cincinnati Reds.

Davis’s arm trouble flared up again in the spring of 1940. He was a throw-in in another big trade in June, when the Cardinals sent him with the temperamental slugger Joe Medwick to Brooklyn for four “obscure players” and a pile of money. Dodgers president Larry MacPhail called it the biggest deal in baseball history, but Cardinals owner Sam Breadon said the cash was less than he had received for Dean.5 Best estimates are that the Dodgers paid more than $125,000.

Once again Davis joined a team on the rise. Instead of a 34-year-old throw-in, the Dodgers got a valuable 36-year-old pitcher. Manager Leo Durocher later called him “a great clutch pitcher.”6 Davis went 8-7, 3.81 for Brooklyn as the Dodgers rose to second place, their highest finish in 16 years.

“Next year” arrived in 1941 when the Dodgers won their first pennant since 1920. As they battled the Cardinals down the stretch, Davis went 7-2 in August and September. With a final record of 13-7 and a 2.97 ERA, he again led the league with just 1.6 walks per nine innings.

Before Game One of the World Series, Durocher tried playing mind games with the Yankees. He refused to name his starting pitcher and warmed up Davis along with his aces, Whitlow Wyatt and Kirby Higbe. “What difference does it make?” New York manager Joe McCarthy asked.7

Davis got the ball against the Yankees’ best, Red Ruffing.8 New York’s leadoff batter, Johnny Sturm, singled, but Davis retired the side, getting his former San Francisco teammate Joe DiMaggio on a fly ball to left. In the second inning, Joe Gordon turned on a 2-2 fastball and drove it 10 rows deep into Yankee Stadium’s left-field grandstand. Medwick’s leaping catch in left robbed DiMaggio of a home run in the fourth, but New York scored twice more before Davis was relieved in the sixth. He was the losing pitcher in a 3-2 game, his only World Series appearance. The Yankees won the championship in five.

Davis’s hair had turned gray, leading some to wonder whether he was older than the 35 listed in the record books. When the military draft began in 1940, requiring men aged 21 through 35 to register, sportswriters found out that Davis hadn’t signed up. He wouldn’t reveal his age, saying it didn’t matter: “The average pitcher is 30 before he learns that he can’t throw the ball past a hitter’s bat, no matter how hard he can throw.” The Brooklyn Eagle’s Tommy Holmes began calling him “Old Coonskin,” but the nickname didn’t catch on.9

When roommates deserted him because of his snoring, Davis said he was practicing moose calls to get ready for hunting season. He was assigned a single room, making everyone happy.

The Dodgers were sailing toward their second straight pennant in 1942, building a 10-game lead in August. By the end of the month, Davis had won 15 games. Brooklyn continued to play well while the Cardinals went on a historic run, winning 44 of their last 53. The Dodgers finished with 104 victories, but the Cards won two more. Davis went 15-6 with a 2.36 ERA that was third best in the league.

Because of his age, Davis was able to pitch through the war years while most of his teammates went into military service.10 Durocher began giving him at least four days’ rest between starts as he approached and passed his 40th birthday, and he won 10 games in each of the next three seasons.

After 18 years and more than 4,000 innings in the majors and minors, Davis was limited by a sore shoulder in 1945. The next spring, when the real big leaguers returned from the war, the Dodgers released the 42-year-old. Besides winning 158 games, Davis lost 131, and posted an adjusted ERA of 116.

He went down to Triple-A to finish the season with Montreal, where he was a teammate of Jackie Robinson. During the playoffs against Rochester, Davis did unique double duty: He relieved a sick umpire for five innings until he was called in to relieve the Royals pitcher.

Montreal went on to win the Junior World Series against American Association champion Louisville as the 43-year-old Davis pitched a complete game to clinch the victory. Although there was speculation that he would quit while on top, he pitched another year at St. Paul. He took over as the Saints’ interim manager for the last two weeks of the season before leaving baseball.

But he left a memento behind in Brooklyn. While with the Dodgers, Davis took manager Durocher and president MacPhail on a hunting trip where the pitcher shot a gigantic elk. He gave the stuffed head to MacPhail, who hung it on his office wall. When Branch Rickey took over as the Dodgers president, he decided the head was too big to move, so it watched over him. In 1950, Walter O’Malley replaced Rickey and planned to ship the trophy to MacPhail — collect. But Davis wrote to the new Dodger owner, saying he wanted his elk head back. “And he shall have it,” O’Malley said.11

Davis had made his home in Southern California since his early 20s, first living with a sister in Los Angeles. He settled in Asuza, an LA suburb, and sold real estate for the rest of his life.

In 1965 Orioles outfielder Curt Blefary won the American League Rookie of the Year award. The Brooklyn native, born in 1943, was named for Curt Davis.12 Davis suffered a stroke that same year and died at age 62 on October 12, 1965. His second wife, Lennis, survived; how his first marriage ended is not known. No children were listed among the survivors.

Davis kept his secret until the end. His obituaries shaved a year off his age.13

Acknowledgements

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Photo credit: The Sporting News/Conlon Collection

Notes

1 Harold Parrott, “Both Sides,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 18, 1942: 15.

2 Frederick G. Lieb, “Curt Davis Started Pitching Career As Lumberjack,” The Sporting News, September 14, 1939: 3.

3 Bob Paul, “Davis on Stand,” Philadelphia Daily News, March 31, 1936, in Davis’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

4 “Thinks He Was Robbed,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 25, 1938: 14.

5 “Sid Keener’s Column,” St. Louis Star-Times, June 13, 1940: 28.

6 Leo Durocher with Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1975), 120.

7 Gerald Eskenazi, The Lip (New York: William Morrow, 1993), 134.

8 I spent entirely too much time trying to figure out why Durocher chose Davis for Game One, rather than one of his 22-game winners. The Yankee lineup included five left-handed hitters, so it should not have been especially vulnerable to Davis’s sidearm delivery. Davis had eight days’ rest, but Higbe had six and Wyatt five. All three had pitched well in September. You might think Durocher didn’t want to “waste” one of his best starters against Ruffing, but it’s hard to imagine Durocher conceding defeat in any game, especially not the first game of the World Series. Besides, two Yankee pitchers had better ERAs than Ruffing’s. The decision looks like one of Durocher’s well-known hunches.

9 Tommy Holmes, “Clearing the Bases,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 21, 1942: 2C.

10 After the United States entered the war, men aged 18 through 64 were required to register for the draft, but few over 40 were called up.

11 Holmes, “New Dodger Skipper and an Elk’s Head,” Brooklyn Eagle, November 8, 1950: 23.

12 Doug Brown, “Blefary Bites Hand That Once Fed Him,” The Sporting News, May 29, 1965: 7.

13 “Curt Davis, Former Mound Star With Four N.L. Clubs,” The Sporting News, October 23, 1965: 34.

Full Name

Curtis Benton Davis

Born

September 7, 1903 at Greenfield, MO (USA)

Died

October 12, 1965 at Covina, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.