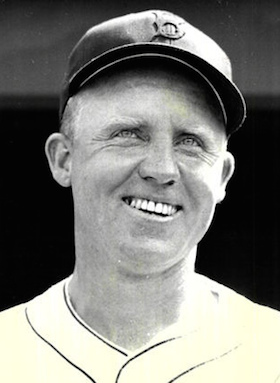

Skeeter Newsome

Skeeter Newsome was a “mighty handy young man.” That’s how a Boston Herald headline writer described him in 1941. He was a shortstop (appearing in 12 seasons at the position, for a total of 902 games), second baseman (9 seasons, 149 games), and third baseman (8 seasons, 49 games). He even played a game in right field and a game in left. His career fielding percentage is .959, with little variation from position to position.

Skeeter Newsome was a “mighty handy young man.” That’s how a Boston Herald headline writer described him in 1941. He was a shortstop (appearing in 12 seasons at the position, for a total of 902 games), second baseman (9 seasons, 149 games), and third baseman (8 seasons, 49 games). He even played a game in right field and a game in left. His career fielding percentage is .959, with little variation from position to position.

There were two Newsomes who played in the big leagues, and one Newsom, and they all played at one time or another for the Boston Red Sox. Their careers overlapped, and from 1941 to 1943 both Skeeter and Dick were on the team at the same time. Pitcher Bobo Newsom had been with Boston briefly in 1937 and he pitched for other teams into 1953. There were more Skeeters than Newsomes; nine of them. Not to mention an entire minor-league team in Jersey City.

Skeeter was born Lamar Ashby Newsome in Phenix City, Alabama, on October 18, 1910, and he was born into a large family. His father, John, was a foreman at a cotton mill in Phenix City and his mother, Mattie (Estes) Newsome, had borne nine children. Lamar was the eighth of the nine, with six older brothers, one older sister, and one younger sister.

Phenix City stands on the west bank of the Chattahoochee River, which separates the city from Columbus, Georgia, to the east. He went to Phenix City public schools at first, but then the family moved across the river and he finished up elementary school in Columbus, and graduated from Columbus High School in 1930.

Despite standing just 5-feet-9 and being listed at 155 pounds, he earned the nickname “Skeeter” from friends who “thought he wasn’t much larger than a mosquito.”1

Skeeter was a bit of a star in basketball for the Columbus High Blue Devils in his senior year, taking the team to the state finals and only losing, to Savannah, in the final game. He was the team captain and, the Macon Telegraph reported, the Columbus team’s “courageous captain … Lamar ‘Skeeter’ Newsome won a permanent place in the hearts of Macon’s fans by his spectacular playing. Newsome scored 22 points against Savannah last night for a high total of 62 for tournament play, giving him the honor of being the leading individual scorer of the tournament, a highly coveted honor in itself.”2

As early as 1927, he’d been making news for his baseball playing, hitting a homer for the “crack amateur baseball nine” Crimson Juniors, beating the Perkins Hosiery Mills, 11-3, in a May game at Columbus.3 Skeeter’s older brother “Frog” (Freddie) was already making a name for himself in football for Mercer College. In fact, all the boys played baseball in the neighborhood growing up, on a field they cleared near their house.

By 1929, the local Columbus newspaper said that Skeeter at shortstop was “a show all by himself. He can field them cleanly and has a rifle shot throw to first. And when he leans into a ball the fielders have to get on their horses for this little fellow wields a mean willow.”4 He also starred at football, a halfback, no less, and one headline said a lot: “Devils Rejoice At The Return Of Newsome.”5 It’s one thing to play three sports in high school; it’s another thing altogether to be named captain of the team in three different sports.6 Skeeter weighed 125 pounds when he first joined the football team as a freshman.

The year Newsome graduated – 1930 – was the year that he started playing baseball professionally, as a shortstop for the Talladega Indians in the Georgia-Alabama League. It was Class-D ball; he hit .284 with five homers and recorded a .915 fielding percentage. The team disbanded on August 14 and he was able to find a position with the Evansville Hubs in the Three-I League, and had already earned one subhead: “Newsome, Petrie Scintillate as Evansville Bows in Defeat.” He was described as “the little shortstop Eddie Goostree brought to town from the Georgia-Alabama League” who “came up with everything hit toward short, making three real spectacular stops.”7 Tigers scout Goostree signed Newsome to a Detroit contract, calling him his “fastest billy-goat.”8

Newsome played for Evansville in 1931, batting .262 in 115 games. In late June he applied for a marriage license at the clerk’s office to marry Esther Louise Perkins of Columbus, saying at the time that he hoped it wouldn’t end up in the Courier. He was assured it would not. It did. And he took a lot of ribbing from his teammates. Manager Bob Coleman said, in Newsome’s earshot, “Yeah, they called me up and said there was a little boy wanting a marriage license. They asked me if I knew him and how old he was. I told them that he lived in Georgia, that he must be at least 16 years old, and that he seemed to be a very good boy.”9 The couple married the day after Christmas. Their first child, Betty Louise, was born in 1936.

In February 1932 the news broke that Newsome would be playing for Beaumont that year.10 He played most of the year (77 games) for the Beaumont Exporters in the Class-A Texas League, hitting .258 but during the season he also worked 22 games in the Three-I League for Decatur. (Bob Coleman was manager.) He was with Beaumont again at season’s end; the Exporters won the pennant, but then bowed to Chattanooga in the Dixie Series. In 1933 it was Beaumont and then the Tulsa Oilers. Newsome played a full 153 games for Tulsa in 1934, and then was brought into the Philadelphia Athletics system. Tulsa president Art Griggs sold his contract to Connie Mack in September 1934.11

Newsome made the team and stuck with the Athletics all year long, mostly filling in for shortstop Eric McNair but managing to get into 59 games, 24 at short, 13 at second, four at third base, and one in right field. His first hit was a double, in his second game. He hit one home run, in the first game of a September 28 doubleheader, a solo homer in the seventh inning off Bobo Newsom that started the scoring against the visiting Senators, in a game that Philadelphia won in the 11th. He hit for a .207 average and drew only five bases on balls (.233 on-base percentage). Still, he was there for defense. Mack reportedly called Newsome “the best fielding shortstop I have ever seen.”12

Newsome played for Mack for five full seasons, 1935-39, averaging more than 84 games per season. He did a better job of getting on base, with a .280 on-base percentage (.233 BA) over the stretch. He worked in the offseasons as a basketball referee in the Columbus community league.

Newsome’s 46 RBIs in 1936 were his high for the A’s, in 127 games. He held out for a while heading into the 1937 season, but it didn’t seem to negatively affect his play. He hit for a higher average, and scored more runs, though he didn’t drive in as many. He missed more than a month after a beaning in an exhibition game. He hit another homer in September, again off Bobo Newsom. Two homers, both off a pitcher with a similar name – “He must be my cousin,” Skeeter said.13

On April 9, 1938, Newsome hit a homer in an exhibition game, in Portsmouth, Virginia – and then got beaned his next time up, hit in the temple, knocked out cold, and was taken to the Naval Hospital for observation. This was a bad one, a fractured skull; he couldn’t get into a game until July 24, when he pinch-ran in both halves of that day’s doubleheader, and then didn’t play again until September 4. He appeared in only 17 games all year long. At the time, Connie Mack was a strong advocate for protective headgear.14 In Skeeter’s obituary, it was noted, “Newsome claimed that he was the first player to wear a batting helmet. After being beaned in the head twice, the second time suffering serious injuries, Athletics manager Connie Mack wouldn’t let Newsome return to action until he wore some type of head protection.”15 He wore an aluminum helmet of some sort in late 1938, then a fiber helmet in 1939.16

The numbers Newsome put up in 1939 were right in line with his prior work for the Athletics: 99 games, a .222 average (.277 OBP). He tied a record on May 15 for the most putouts by a shortstop in a nine-inning game – nine putouts. In December the Athletics released him outright to the Baltimore Orioles (International League). Newsome played for Baltimore in 1940; he hit .277 in 148 games. Baltimore was a Phillies affiliate; Newsome was in the other Philadelphia organization. But not for long. Soon after the International League season was over, the Phillies traded him to the Boston Red Sox for a minor leaguer, a player to be named later, and an undisclosed amount of cash. It doesn’t look that they assigned a lot of value to him.

The Red Sox wanted a solid backup for Joe Cronin at shortstop and hoped that, as a right-handed hitter, Newsome would find Fenway‘s left-field wall helpful.17 The deal was done on September 5. Three days later, the Red Sox signed another Newsome, pitcher Dick Newsome from the San Diego Padres. Over the winter, Skeeter Newsome worked as a “special representative” for the Reliance Life Insurance Co. of Columbus.

The two Newsomes met at spring training 1941, and posed for a photo running in the March 6, 1942, Boston Herald. And Skeeter was glad to be back in the majors, saying, “I don’t care if I have to help the greenkeeper mornings as long as I stay with this club.”18

The team made good use of Skeeter Newsome for five years, particularly during the war years of 1943-45. He played in 93 games in 1941 (69 at shortstop and 23 at second base), and hit for a .225 average (.296 on-base percentage). After Cronin did step back from shortstop work, Johnny Pesky beat Newsome out for the shortstop slot in 1942. Pesky collected 205 base hits, and got into almost every game. Bobby Doerr was solid at second base. Newsome got into only 29 games, though he hit .274.

By 1942, Pesky was in the Navy. Newsome, with his head injuries, and being 31, wasn’t likely to get called. The path was clear, and he got into 114 games in 1943, batting .265. (He did actually take, and pass, a physical for the Navy in February 1945, but was never called.) In 1944 it was 136 games, with 41 RBIs. His best year was 1945: he hit .290 and drove in 48 runs – both career highs.

Anticipating the return of Johnny Pesky and several other veterans, the Red Sox were willing to let Newsome go and accepted a $15,000 offer from the Philadelphia Phillies on December 12. Newsome had joined Phillies manager Ben Chapman for a postseason series of exhibition games on a team dubbed the “Dixie Walker All-Stars,” and the purchase was thought to have reflected Chapman’s being impressed with Newsome’s work.19

Here he was back in Philadelphia, this time playing for the National League ballclub in the city – but playing in the same ballpark. Both teams played in Shibe Park, which was owned by the Athletics. Newsome turned in two more seasons – 1946 and 1947 – that were probably more or less as the Phillies had expected. He averaged .231 over the two seasons in a combined 207 games. They were his last two years in the majors. On September 24, 1947, he was released, effective at the end of the season four days later.

Newsome played one more year, a successful one with the Seattle Rainiers in 1948. He then moved into managing; he began as player/manager with the Portland (Maine) Pilots in 1949, and played full seasons with them and for the Wilmington (Delaware) Blue Rocks in the Interstate League in 1950. The Blue Rocks led the league in 1950.

He began cutting back – playing 61 games in 1951 and 31 games in 1952 while managing Terre Haute, to a first-place finish in ’51 and second place in ’52; Terre Haute won the playoffs in 1952. In 1953 Newsome managed Schenectady and played in his last games. He hit only .129. It was time to put the glove and bat away.

Newsome managed through 1960 – Syracuse in 1954 and 1955, hometown Columbus in 1956 and 1957, and Birmingham in 1959 (another first-place finish) and 1960.

From 1960-74, Newsome was an account executive for WTVM Channel 9 in Columbus. He was also active in civic affairs.

Lamar Newsome died at the Oak Manor Nursing Home in Columbus on August 31, 1989. He had suffered prostate cancer for nine months before finally expiring. He was survived by his wife, Louise, one son (James), and three daughters (Elizabeth, Linda, and Susan), as well as a sister, two brothers, and 18 grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Newsome’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Felton Gordon, “Newsome’s 5-Year Major League Career Is Halted By Release to Baltimore,” Columbus Daily Enquirer, December 10, 1930: 11.

2 Jimmy Jones, “Savannah Triumphs Over Columbus To Win G.I.A.A. Basketball Tourney,” Macon Telegraph, March 2, 1930: 9.

3 “Crimsons Beat Ramsey 11 to 3,” Columbus Daily Enquirer, May 26, 1927: 4.

4 “Hubbard Plays Manchester Nine,” Columbus Daily Enquirer, June 1, 1929: 3. Newsome was playing that summer for Hubbard Hardware.

5 James Ford, “Devils Rejoice At The Return Of Newsome,” Columbus Daily Enquirer, September 26, 1929: 3.

6 Felton Gordon, Columbus Daily Enquirer.

7 Daniel W. Scism, “Krueger Pitches Trax to Shutout Win in Opener, 4-0,” Evansville Courier and Press, September 7, 1930: 9.

8 Daniel W. Scism, “Sew It Seams,” Evansville Courier and Press, May 14, 1937: 23. Felton Gordon wrote that Newsome was signed just before he finished high school.

9 “As Seen from the Coop,” Evansville Courier and Press, June 24, 1931: 11.

10 “‘Skeet’ Newsome to Play with Beaumont, Tex., 9 During 1932 Season,” Evansville Courier and Press, January 24, 1931: 15.

11 Associated Press, “Mack Buys New Infielders For Athletics Squad,” Los Angeles Times, September 23, 1934: E3; George White, “Sport Broadcast,” Dallas Morning News, June 20, 1935: II, 2.

12 Felton Gordon.

13 Kenneth Gregory, “Pro Gridders Battle Sunday,” Charleston (South Carolina) Evening Post, January 31, 1938: 8. There was no known family connection.

14 Gordon Cobbledick, “Plain Dealing,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 31, 1938: 14-15.

15 “Former baseball great Newsome dies at age 78,” Columbus Ledger-Enquirer, September 2, 1989: B-5.

16 A photograph of Newsome with the helmet ran in several papers including the Boston Globe, May 7, 1939: B26. Red Smith later wrote that the first helmet was far from sturdy. “One day a little pop foul hit the top of the batting cage, rattled around there and dropped, a spent ball, onto Newsome’s cap. It split the helmet in two. Skeeter never told Connie about that.” Red Smith, “Views of Sport,” New York Herald Tribune, uncertain date 1949. Clipping found in Newsome’s Hall of Fame player file. Dan Daniel, in the March 21 New York World-Telegram, said Newsome wore a “steel helmet under his cap.”

17 Ed Rumill, “New Shortstop Purchased by Boston From Baltimore for Infield Next Season,” Christian Science Monitor, September 5, 1940: 15.

18 Fred Knight, “Skeeter Newsome Fine Utility Player,” March 12, 1941, datelined story from unidentified clipping in Newsome’s Hall of Fame player file.

19 Virginia Bailey, “$15,000 Price Reported Paid for Shortstop,” Columbus Daily Enquirer, December 13, 1945: B-5.

Full Name

Lamar Ashby Newsome

Born

October 18, 1910 at Phenix City, AL (USA)

Died

August 31, 1989 at Columbus, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.