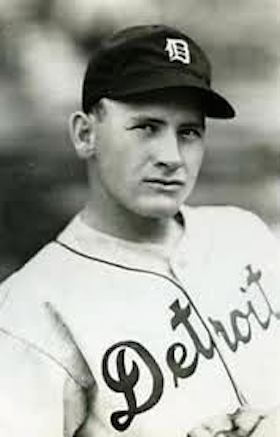

Dizzy Trout

Consumer alert: Some of the stories repeated here probably are not true. The difficulty is, we don’t know which ones.

Consumer alert: Some of the stories repeated here probably are not true. The difficulty is, we don’t know which ones.

Dizzy Trout was a magnet for tall tales. Many of the stories Trout told, and those told about him, can’t be verified, but they’re too much fun to pass up.

There’s the Ted Williams story: Trout struck out Williams to end a game, then asked Ted to autograph the ball. Williams turned and stomped away. The next time they met, Williams poled a long home run. As he rounded the bases, he called out, “I’ll sign that one if you can find it.” True? Undetermined. A later pitcher, Pedro Ramos, told the same story on himself.[fn]Bill Madden, “Ted Williams and Dizzy Had a Ball,” New York Daily News, July 17, 1987, in Trout’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York; Rob Neyer, Rob Neyer’s Big Book of Baseball Legends (New York: Fireside/Simon & Schuster, 2008), 128.[/fn]

There’s the Luke Appling story: The White Sox’s Hall of Fame shortstop was notorious for his ability to foul off pitches at will. “Once I hit a dozen in a row off Dizzy Trout and he got so sick and tired of it, he threw his glove at me and hollered, ‘You so-and-so, let’s see you foul that.’” Appling did. True? Appling said it was.[fn]William Leonard, “Win or Lose, Sox Fans Cheered Luke,” Chicago Tribune, July 10, 1960, B38.[/fn]

One sportswriter said, “He had a beautiful sense of humor and sometimes a temper to match.”[fn]“Obituaries,” The Sporting News (hereafter TSN), March 11, 1972, 44.[/fn] Trout’s temper held back his career. Once he dragged a heckler out of the stands and began pummeling him. After Diz was ejected, he thumbed his nose at the crowd. True? Yes. It happened on September 11, 1942, in Detroit.[fn]“Pitcher Trout Attacks Fan as Tigers Lose,” Associated Press-Chicago Tribune, September 12, 1942, 19.[/fn]

When he was still a 21-year-old minor leaguer, Trout’s legend had grown so large that The Sporting News invited him to write his life story. Appropriately, it appeared in the paper’s April Fool’s Day issue. Paul Howard Trout was born on June 29, 1915, in Sandcut, Indiana. “This town is not on any map,” he wrote, “due to the fact that the wind keeps blowing the sand over and over and the town never stays in one place for very long at a time.”[fn]“‘They Said I Had a Hop on My Baby Rattle,’ Writes Dizzy Trout in his Own Life Story,” TSN, April 1, 1937, 10.[/fn] Google Maps found Sandcut just north of Terre Haute, but it may have blown away by now.

Paul was the youngest of four children of Virgil and Emma Trout. Virgil was a coal miner and tenant farmer. Paul said, “I attended 12 different schools due to the fact that the rent came due on the first of every month and Pa most always had to move to another farm.”[fn]Paul Mickelson, “Following the Sports Trail,” Associated Press-Baton Rouge Advocate, March 13, 1937, 11.[/fn] Paul’s mother died when he was 15. When his father remarried, the boy didn’t get along with his stepmother and moved out, living with relatives or sleeping under bridges.

He said he never held a baseball until he was 14, but played ball with rolled-up rags and walnuts. “I even could throw hard at an early age. They say I had a hop on my baby rattle.”[fn]“They Said I Had a Hop.”[/fn] Walking home from school, he threw rocks at the glass insulators on utility poles. When he began breaking the glass, “my chum and I then went into the woods and killed flying squirrels with green walnuts.”[fn]Paul Trout, “How I Broke into Pro Ball,” undated handwritten manuscript in Trout’s HOF file.[/fn]

In the summer of 1934, when he turned 19, Trout hopped a freight train to Chicago to pitch semipro ball and talked his way into tryouts with the White Sox and Cubs. The right-hander pitched batting practice for both teams, but neither showed any interest in signing him.

Returning to Terre Haute, he got a better reception from the local Three-I League team. He showed up at the Tots’ tryout camp wearing bib overalls and won a contract in 1935. After a 13-8 season, he was sold to Indianapolis at the top minor-league level, Class Double A.

By the next spring Paul Trout had given himself the nickname “Dizzy.” He wanted to be as famous as Dizzy Dean, who was the biggest name in baseball after Babe Ruth retired. Trout explained, “It ain’t because I’ve got as much stuff as Diz, but they call me Diz because I talk as much as Diz.”[fn]H.G. Salsinger, “Mickey Cochrane Hooks a Trout, Lands a Diz.” TSN, March 11, 1937, 8. Trout was called “Dizzy” in a Sporting News story a year earlier: “Training with the Minors,” April 9, 1936, 8. [/fn] He even invented a creation myth: He said he was caught in a storm at the Toledo ballpark and spotted an awning on the center field wall, a good place to duck out of the rain. He ran toward it, but smashed head-on into the bricks because the awning was painted on the wall. For that, he claimed, teammates began calling him Dizzy.

Trout went 8-7 with a 5.12 ERA for Indianapolis, but he finished strong with a two-hitter and a three-hitter in late-season starts. In one of those games he allowed no hits until the ninth inning. The Detroit Tigers acquired him and invited him to spring training.

He hit Lakeland, Florida, in February 1937 like an Indiana tornado. Sportswriters couldn’t get enough of the hayseed motormouth. “I’m here and the American League can rest assured that I’ll make more noise than Dean,” he said. “Right off I can tell you, son, that the folks in Detroit haven’t seen a fastball yet until they’ve seen Dizzy Trout flag one over that rubber.”[fn]“Dizzy Trout, Pitcher, Tells Tigers He’ll be American League Dean,” New York Herald Tribune, March 13, 1937, in Trout’s HOF file.[/fn] He delighted photographers with funny hats and a fake moustache. Between pitching assignments he sat in the stands and told the customers all about himself.

Detroit manager Mickey Cochrane went along with the show, to a point. The Tigers’ March 28 exhibition game against the St. Louis Cardinals featured both the original Dizzy and the pretender. Trout razzed the Cardinals nonstop until he took the mound and the Gashouse Gang turned the fury of their own bench jockeys on him. He blew sky-high, couldn’t find the plate, then threw a tantrum in the dugout after he was mercifully relieved. The real Diz advised the busher, “If I was you I’d quit poppin’ off until I’d went out there and won myself some ball games.”[fn]H.G. Salsinger, “Temper-Taming Helps Trout Triumph,” TSN, August 31, 1944, 3. Contrary to some later accounts, the two Dizzys did not pitch against each other. Dean worked the first three innings for St. Louis. Trout relieved in the fifth for the Tigers and allowed three runs on three hits and three walks in one inning.[/fn]

A few days later Trout was back in form, borrowing a policeman’s motorcycle to ride around the ballpark. Cochrane had seen enough. He shouted, “You can keep riding that thing to Toledo because that’s where you’ll be this year.”[fn]“Obituaries,” TSN.[/fn]

Trout went 14-16 for the Toledo Mud Hens, but his name was mud in Detroit. The Tigers didn’t bother to invite him to spring training in 1938 and demoted him to Beaumont in the Texas League. Tutored by former Tigers pitching star Schoolboy Rowe, who was trying to come back from a sore arm, Trout racked up a 22-6 record with a 2.12 ERA and won the league’s Most Valuable Player award as Beaumont cruised to the pennant.

If the league had had a Most Popular Player award, he could have won that, too. He would walk off the mound in mid-inning and go to the dugout for a drink of water. When his glasses fogged up in the Texas heat and humidity, he pulled out a red bandana to wipe them. One day he ran hard to second base, then called time and sat down on the bag to catch his breath.

At 23, 6-foot-2 and 195 pounds, Trout appeared to have grown into a fine prospect as well as a crowd pleaser. But Detroit sportswriter Harry Salsinger dismissed him: “He cannot control his emotions. He is likely to go into an emotional stampede in any crisis.”[fn]H.G. Salsinger, “The Umpire,” Detroit News, September 29, 1938, in HOF file.[/fn]

When he showed up for spring training with the Tigers in 1939, Trout promised, “I’m all through with that clown stuff.”[fn]Leo Durocher Tries to Sign Van Mungo,” Omaha World-Herald, March 6, 1939, 10. [/fn] He still lit up Lakeland with two-toned shoes, brightly colored socks, and loud ties, but mostly kept his mouth shut and made the team. In his major-league debut on April 25, he held the St. Louis Browns hitless for three innings before they knocked him out with four runs in the fourth. He didn’t get his first win for nearly a month. On May 24 the last-place Tigers beat the first-place Yankees, 6-1, ending a 12-game New York winning streak, as Trout struck out six in his first complete game.

A teenage fan, Ruth Ortmann, delivered a chocolate cake to his hotel to celebrate the victory. When Trout shared the cake with the other Tigers, of course they kidded him about his admirer. He left tickets for Ruth and her family and greeted them at Briggs Stadium before a game. According to teammate Birdie Tebbetts, Trout said, “I met the girl I’m going to marry.”

“The girl who cooks the cakes?”

“No, her sister.”[fn]Birdie Tebbetts with James Morrison, Birdie: Confessions of a Baseball Nomad (Chicago: Triumph, 2002), 51. [/fn] He proposed to Pearl Ortmann on their first date. They were married in September.

After his rookie year, Trout was caught up in Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis’s war on the farm system. Trying to keep the minor leagues independent, Landis had declared dozens of St. Louis Cardinals farmhands free agents two years earlier because of rule violations. In January 1940 the commissioner freed 92 Detroit players, wiping out more than half of the Tigers’ farm system. Three young major leaguers – Trout, outfielder Roy Cullenbine, and infielder Benny McCoy – were on the list because Landis found that they had been illegally kept in the minors.

Trout’s freedom lasted only 24 hours. The Tigers convinced the commissioner that they had handled Trout’s contract by the book and he was restored to the roster. He just missed a big payday. McCoy signed with the Philadelphia Athletics for a $45,000 bonus; Cullenbine got $25,000 from Brooklyn. Trout, naturally, believed he was worth more: “Call it $90,000, and nobody can accuse me of boasting.”[fn]John Lardner, “From the Press Box,” North American Newspaper Alliance-Washington Star, March 12, 1940, 14.[/fn]

Trout was an effective pitcher in his first four seasons in the majors, with ERAs better than average, but the team and the sportswriters labeled him a disappointment because of his wildness, inconsistency, and outbursts of temper. A pitcher was judged primarily by his won-lost record; Trout never had a winning season.

While Detroit won the pennant in 1940, he spent most of his time in the bullpen. In a rare start, his September victory over Philadelphia boosted the Tigers into a first-place tie. That earned him a start in the World Series against Cincinnati. In Game Four he gave up six hits and three runs in two-plus innings and was the losing pitcher.

Trout was a fastball pitcher with a curve and a sinking forkball. Manager Del Baker wouldn’t give up on him because Baker believed in his stuff. But after Baker removed him from a game in 1942, the enraged Trout charged the manager in the dugout. Teammate Doc Cramer wrestled him away before he could do any damage to Baker or his own career. That same year he attacked a heckler in the stands.

Two developments in 1943 turned Trout’s career around. A large number of players went into military service – more than 200 present and former big leaguers, three times as many as the year before – and the Tigers got a new catcher, Paul Richards. Richards was a wartime replacement, a 34-year-old former minor league manager, who helped Trout get his temper under control. When the pitcher showed signs of blowing up, Richards held the ball between pitches, signaling Trout to slow down and take a breath. The improvement was dramatic. Trout’s 20 wins and five shutouts tied the Yankees’ Spud Chandler for the AL lead and his 2.48 ERA was fifth best. Trout did double duty as Detroit’s top reliever, finishing 14 games with six saves.

The Tigers had a second wild, hotheaded pitcher who had been an even bigger disappointment than Trout. Hal Newhouser was a phenom, reaching the majors when he was 18, but the left-hander couldn’t control his fastball or his temper. Unlike Trout, he too often vented his rage on his teammates. Fellow pitcher Virgil Trucks said, “He was probably disliked more than any ballplayer on any club I was on.”[fn]Frederick Turner, When the Boys Came Back (New York: Henry Holt, 1996), 19.[/fn] Newhouser seemed to have turned the corner in the first half of 1943 with a 1.32 ERA, then lost 12 of his last 13 decisions.

Trout and Newhouser blossomed into a pair of aces in 1944. Riding their arms and the bat of Dick Wakefield after he was discharged from the Navy in midseason, the Tigers climbed from seventh place in July to a fight for the pennant that went down to the last day. Manager Steve O’Neill started Trout and Newhouser in 17 of 28 September games. Detroit led the St. Louis Browns, of all teams, by one game with four to play. The Tigers had drawn a friendly schedule; they finished the season against last-place Washington while St. Louis had to face the third-place Yankees.

Trout started the second game of the Washington series on just two days’ rest. The Senators routed him in a 9-2 victory to drop the Tigers into a tie for first. The next day Newhouser, also on two days’ rest, won his 29th game, but the Browns beat the Yankees to keep the race deadlocked. Trout took the ball in the final game after only one day off. He had already pitched 343 2/3 innings, the most in the majors. In his 347th inning the Senators scored three times and made him a loser. The Browns won their finale to claim the only pennant in their history.

Newhouser’s 29 victories and Trout’s 27 were the most by two teammates since the deadball era. Trout led the league in ERA, shutouts, complete games, and innings pitched, with Newhouser second in all categories. Newhouser led in wins and strikeouts, with Trout second in both. Trout’s 33 complete games and 352 1/3 innings were the most by any pitcher in 21 years. For good measure, he led AL pitchers in hits, home runs, RBI, assists, and double plays.

In the Most Valuable Player balloting, 10 sportswriters put Trout number one; seven voted for Newhouser. But the point system – 14 points for a first-place vote, 9 for second, 8 for third, down to 1 point for tenth – clinched the award for Newhouser, 236 to 232. It was the first of his two consecutive MVP awards, probably the reason he was elected to the Hall of Fame.

The two aces were classified 4-F, medically unfit for military service. Newhouser had a heart murmur. Trout was disqualified for poor eyesight and hearing. Both men worked in war plants in the offseasons and Trout was an enthusiastic public speaker on behalf of war bonds, the USO, and the Red Cross. Urging civilians to buy as many bonds as they could afford, he told the story of an Indiana farmer who sold a cow for $50. The cow produced only one pint of milk a day, so the disappointed buyer demanded his money back. The seller protested, “She’s giving all she’s got.”[fn]Sam Greene, “Trout Rises to his Obligations to U.S.,” TSN, February 18, 1943, 3.[/fn]

Trout had given all he had in 1944. The next spring it appeared the brutal workload had caught up with him. He sat down in May for two weeks. When he returned, manager O’Neill drove him without letup, using him in relief between starts. Trout soon broke down again. He complained of a sore muscle in his side and lower back pain, but he took his starting turn, plus relief stints, in August and September as the Tigers battled for the pennant with another unlikely contender, the Washington Senators.

Trout pitched 10 times in 20 days in September – six starts and four relief appearances – and staggered to the end, battered in his last two starts. The Tigers clinched the pennant on the final day when Hank Greenberg’s ninth-inning grand slam beat the Browns to give Newhouser his 25th victory.

The 1945 World Series against the Chicago Cubs matched draft rejects and baseball retreads. Seven of Detroit’s eight everyday players were past 30; the center fielder was 40 and the bench included a 42-year-old pinch hitter. Sportswriter Grantland Rice commented, “Apparently most of the Tigers should either be in the hospital or the old soldiers’ home.”[fn]Grantland Rice, “The Sportlight,” syndicated column in Canton (Ohio) Repository, October 3, 1945, 18.[/fn]

The Cubs took two of the first three games on Detroit’s home field. O’Neill held Trout back for the fourth game, when the Series moved to Chicago.[fn]Even though the war was over, the World Series was scheduled according to wartime travel restrictions, with three games in Detroit followed by four in Chicago.[/fn] With 12 days’ rest, he overpowered the Cubs, allowing only an unearned run on five hits. After the last out Trout shook hands with catcher Richards and plate umpire Jocko Conlan, then swept off his cap and bowed to the grandstand. “Well, I just threw that atom ball today, that was the best thing I had out there,” he told the writers. “You just throw it at ’em, and they can’t do a thing with it.”[fn]James P. Dawson, “Trout Gives Credit to his ‘Atom Ball,’” New York Times, October 7, 1945, S1. A Chicago tavern owner, Billy Sianis, tried to bring his pet goat to the game, but was kicked out of Wrigley Field even though he and the goat had tickets. Thus began the Cubs’ “Billy Goat Curse,” the obvious explanation for their failure to return to the World Series since 1945.[/fn]

Two days later Trout relieved in the eighth inning of Game Six with the score tied, 7-7. He worked four shutout innings, but lost in the 12th on a bad hop. Stan Hack’s line drive hit a sprinkler head in left field and bounced past Hank Greenberg to drive in the winning run. The Tigers rebounded in Game Seven behind Newhouser to win the Series.

Despite his injuries, Trout finished 18-15 with a 3.14 ERA. But his success, like Newhouser’s, was suspect because they had excelled against war-depleted rosters. They had to prove themselves anew in 1946, when the real major leaguers came back.

They did. Newhouser: 26-9, 1.94. Trout: 17-13, 2.34. Their won-lost records suffered as the Tigers fell out of contention after the war, but they were still star-caliber pitchers. In 1948 Trout, at 33, missed more than a month with a sore arm and was largely ineffective once he returned. A new manager, Red Rolfe, sent him to the bullpen in 1949 and seemed to write him off. Trout worked only 59 1/3 innings. After two more years, returning to double duty as a starter and reliever, “Trout had just about reached the end of his useful days in Detroit,” local sportswriter Watson Spoelstra said.[fn]Watson Spoelstra, “Gehringer Clinches Title as Detroit’s Top Swapper,” TSN, June 11, 1952, 7.[/fn]

On June 3, 1952, Trout was essentially a throw-in as part of a nine-player deal. The Tigers sent star third baseman George Kell, outfielder Hoot Evers, and infielder Johnny Lipon, along with Trout, to Boston for first baseman Walt Dropo, shortstop Johnny Pesky, third baseman Fred Hatfield, outfielder Don Lenhardt, and pitcher Bill Wight. The trade was a salary dump by Detroit after the death of the club’s generous owner, Walter Briggs. Kell, Trout, and Evers were each said to be making at least $30,000.

Trout was approaching his 37th birthday and had been with the Tigers longer than any other active player. The Red Sox, if they wanted him at all, wanted him as a reliever, but injuries to others forced him into the starting rotation. He won his first four decisions and went 9-8, 3.64, after the trade.

Still, it was not certain that Boston would invite him back in 1953. Trout didn’t wait to find out. He told a reporter he had lost his fastball: “When it got to the plate it was so slow, two pigeons were roosting on it in mid-air. I decided to quit.”[fn]Bob Addie, “Sports Addition,” Washington Post, March 30, 1955, 30.[/fn] More to the point, he had six children to support and jumped at a firm job offer. In December he signed on as color analyst for the Tiger’ radio and TV broadcasts.

If ever there was a natural broadcaster, it was Dizzy Trout. If ever there was a recipe for trouble, it was Dizzy Trout sharing a booth with Van Patrick. The Tigers’ play-by-play announcer was a respected pro who also broadcast Notre Dame and Detroit Lions football. Patrick took himself and his work seriously. “Seriously” was seldom part of Trout’s homespun vocabulary. Patrick corrected Trout’s grammar and Trout corrected Patrick’s analyses.

“Hell, I should be doing the beer commercials,” Trout declared. “I’m the one who drinks the stuff.”[fn]Steve Trout with Larry Names, Home Plate (Murray, Utah: E.B. Houchin, 2002), 16.[/fn] One day a Tigers pitcher was getting pounded and when he finally retired the side, Trout said, “I can’t believe this. They’re giving him a standing ovation.” Patrick observed, “It’s, uh, the seventh inning stretch.”[fn]Joe Falls, “The World of Dizzy Trout,” TSN, March 18, 1972, 48.[/fn]

The uneasy partnership lasted three seasons before Hall of Famer Mel Ott replaced Trout in the booth. Now with eight children in his family and needing a job, Trout ran for sheriff of Wayne County, the jurisdiction including Detroit, in 1956. He won the Republican nomination, but he was a sacrificial lamb; he lost the general election in a landslide to the Democrat who had held the office for 26 years.

Trout had pitched in batting practice for the Tigers and in some sandlot games. Soon after his ninth child, Steven, was born in July 1957, he decided to try a comeback at 42. His former catcher, Paul Richards, was running the Baltimore Orioles and signed him for the Triple-A Vancouver farm club. In his first appearance with the Mounties, he struck out six in 6 2/3 innings. After two more relief outings, Baltimore called him up in September.

Trout returned to the majors in Boston’s Fenway Park, on the same mound where his career had supposedly ended almost exactly five years earlier. Weighing more than 220 pounds and looking mighty like a whale, he milked it for maximum drama. On the way in from the bullpen in the eighth inning, he detoured to the dugout for a drink of water and hauled out his trademark red bandanna to wipe his glasses. The Red Sox protested the flapping sleeve on his sweatshirt, so the game was delayed while he took it off. Then he threw two pitches and retired the only batter he faced on an infield popup. But in his next game, against Kansas City, he gave up two singles, a double, and a triple for three runs before he was relieved without pitching for the cycle or recording an out. That ended his comeback.

An attempted political comeback fared no better. In November he failed in a bid for the Detroit city council.

Trout was scuffling to support his family. He put his name on a Detroit restaurant and worked as a bartender and salesman. In 1959 the new owner of the White Sox, Bill Veeck, hired him and the former Yankee pitching star Red Ruffing to run tryout camps around the Midwest. Veeck, who knew a showman when he saw one, soon put Trout to work on the banquet circuit. He served as Veeck’s chauffeur and warmup act, telling stories before introducing the owner to deliver his spiel promoting the team.

Trout had found his niche. After Veeck sold the White Sox in 1961, Trout remained as head of the team’s speakers bureau. He moved his family, now numbering 10 children and his wife’s parents, into a converted convent in a Chicago suburb. People assumed he must be Catholic, but Trout said, “Heck, I’m just a passionate Protestant.”[fn]Steve Trout, Home Plate, 13.[/fn]

The seventh Trout son, Steve, was the only child to pursue baseball seriously. The 12-year-old was playing catch when his father suddenly yelled, “Somebody go get Pearl! This is the little SOB who can pitch! And we can stop having kids, too!” But Trout was not an overbearing Little League dad. His only advice was, “Don’t think, son. Just throw the damn ball.”[fn]Steve Trout, Home Plate, 24, 28.[/fn]

Trout contracted stomach cancer in his 50s. Chicago sportswriters, wanting to pay tribute, created the Good Guy Award and made him the first recipient. He died at 56 on February 28, 1972.

Four years later the White Sox selected left-handed pitcher Steve Trout as their number-one pick in the amateur draft. Bill Veeck, who had bought the team again, overruled his scouts in making the choice. “I was afraid Dizzy would put a curse on me if I didn’t take care of his kid,” he said.[fn]Bill Veeck with Ed Linn, Veeck as in Wreck (repr. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 391.[/fn]

Steve made the majors two years later, beginning a 12-year career. His mother came to see him pitch in Tiger Stadium, where his father had won fame. In 1982, when Steve started against Baltimore, the Orioles scoreboard commemorated Dizzy’s final appearance on the same mound a quarter-century before. The Trouts’ combined victories –170 for Diz, 88 for Steve – were the most by a father and son until the Stottlemyres surpassed them.

A sportswriter once asked Trout how long he had been married. He replied, “Almost six months.” When reminded that he had 10 children, Trout explained, “You see, Pearl and I operate on a six-month basis. If we still love each other after that time, we tack on another six months. It’s worked pretty well so far.”[fn]John P. Carmichael, “The Barber,” Chicago Daily News, March 1, 1972, in Trout’s HOF file.[/fn]

True story.

Additional Source

Larry Amman, “Newhouser and Trout in 1944: 56 Wins and a Near Miss,” Society for American Baseball Research, Baseball Research Journal 12 (1983).

Full Name

Paul Howard Trout

Born

June 29, 1915 at Sandcut, IN (USA)

Died

February 28, 1972 at Harvey, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.