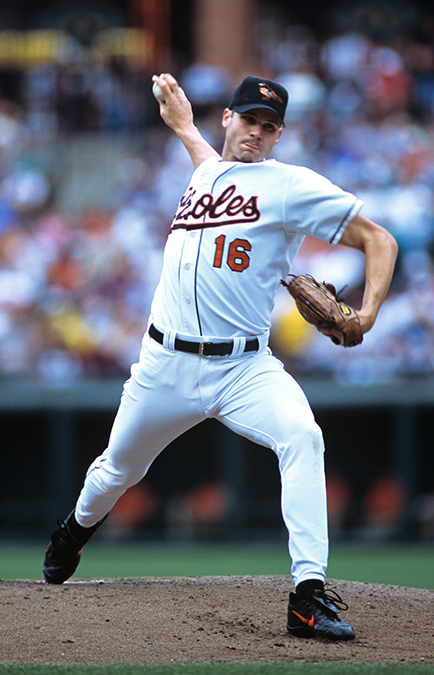

Jason Johnson

Right-handed pitcher Jason Johnson overcame a diagnosis of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus as a youth to forge an 11-year major-league career during which he became the first ballplayer to wear an insulin pump on the field of play.

Jason Michael Johnson was born on October 27, 1973, in Santa Barbara, California, to John and Deanna Johnson. The family moved to Elk Ridge, Utah for a stretch of five years where John Johnson opened and operated a photography store and studio for five years. They later moved to Kentucky when John Johnson got a job offer to work as a district manager at CPI Photo Finishing. John Johnson later in life designed and sold sculptures. Deanna Johnson worked as a respiratory therapist for 20 years before becoming a flight attendant for the final 14 years of her career. The second of five children, Jason had an older brother who died in a car accident at age 16 and three younger sisters. Growing up sports-crazed, he was 11 years old when he developed typical diabetic symptoms including chronic dehydration and fatigue, leading to a diagnosis of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Regarding his diagnosis, Johnson noted in 2006, “My first fear was that I couldn’t play baseball anymore. Baseball and basketball were my two favorite things to do. That was tough, as a kid.”1

Having had an aunt who died as a result of diabetes, Johnson and his family were somewhat familiar with the disease. His father in particular provided encouragement that helped as Johnson recalled in 2006: “My dad said, ‘Don’t let this stop you from doing anything you want to. If you love to play sports, keep doing it. You’re not going to be any different than anyone else when it comes to that.’ That always stuck with me.”2 He grew into a 6-foot-6 baseball and basketball star at Conner High School in Hebron, Kentucky. His major-league playing weight is listed at 225 pounds.3 He was talented enough in basketball to earn a scholarship offers from multiple Division 1 schools including Morehead State and Richmond. Johnson’s first love, however, was baseball, and he turned down the scholarships. He fell out of the MLB draft after a high-profile outing in which he topped out at only 78 mph, more than 10 mph below his normal velocity after having stayed out most of the night before.

After high school Johnson joined an amateur youth travel team in Ohio, the Midland Redskins, where he was quickly offered a tryout with the Pittsburgh Pirates after bird-dog scout Buck Buchanan saw him throw only one pitch. At the tryout he showed a velocity return to the low 90s and was quickly signed by Pirates scout Steve Demeter as a nondrafted free agent in July of 1992.

Once joining the Pirates system, Johnson made his professional debut in Bradenton and advanced slowly, pitching at the Class-A level for his first five seasons while compiling a 15-38 record. Johnson had to carefully monitor his blood sugar during games, virtually between every inning, and related this anecdote in a 2005 interview: “One time when I was pitching in Single-A for the Pirates, the pitching coach realized I was a little shaky. He hid a Coke under his jacket, walked to the mound like he was going to give me a talk and whole infield gathered around so no one could see me bend down and drink the Coke. Everyone acted like we were just talking and, sure enough, in a couple of minutes I was fine and continued to pitch.”4

Johnson’s career and life nearly came to abrupt end in December of 1996 when he was involved in a serious car accident after his Jeep hydroplaned. Johnson wasn’t breathing when found by first responders, but was revived and later found to have a fractured skull, clavicle, and mandible. Johnson made a remarkable recovery and made great strides during the 1997 season, that he credited entirely to gaining better control of his diabetes.5 While starting back with Class-A Lynchburg, he earned a July call-up to Double-A Carolina and a subsequent big-league call-up in late August on the strength of his first winning record as a professional (11-7, and a 3.85 earned-run average, with 155 strikeouts in 156⅔ innings between the two levels).

In his major-league debut, on August 27, 1997, Johnson relieved Steve Cooke in the top of the second inning at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium. Johnson inherited two baserunners and was rudely greeted by Mike Piazza, giving up a three-run home run to the future Hall of Famer on his first pitch in the majors. He pitched three innings of relief on September 1 and two more innings on September 27, for a total of three appearances for the Pirates late in the 1997 season.

Expansion came to baseball for the 1998 season and Johnson’s overall success in 1997 made him attractive in the expansion draft, in which he was taken by the Tampa Bay Devil Rays with their seventh pick. Johnson started the season at Triple-A Durham, but was recalled after only two starts when an injury opened a spot in the big-league rotation. He made 13 starts before being sidelined himself by a stress fracture in his lower back sustained while taking batting practice; the injury kept him out the rest of the regular season. He was 2-5 for Tampa Bay. Johnson was recovered enough to participate in the Arizona Fall League, where he was named AFL Pitcher of the Year and one of the top two right-handed pitching prospects in the circuit on the strength of his league record-tying seven wins for the Grand Canyon Rafters. Highlighting the eventful year, Jason and his wife, Stacey, were married over the All-Star break.

Another change of address was in store for the 1999 season as Johnson was traded to the Baltimore Orioles at the end of spring training for outfielder Danny Clyburn and a player to be named later (Bolivar Volquez). Optioned to Triple-A Rochester, Johnson made eight starts for the Red Wings before being recalled for the remainder of the 1999 season. Over 22 games and 21 starts, he went 8-7, finishing strong on a five-game win streak over his last seven starts. The injury bug bit again as he had to miss his last start of the year due to a broken toe.

Johnson was a favorite to make the Orioles rotation in 2000, but a poor spring training resulted in a return to Rochester. He quickly made his way back to the majors after being named the International League Pitcher of the Week for April 17-23 on the strength of a five-hit shutout. He was unable to build on this success in the majors as he started the year 0-8, despite lasting into at least the fifth inning in 12 of his 13 starts. Returned to Triple-A, he continued to show he had little to prove in the minors with a 1.80 ERA over his five starts and returned to the Baltimore bullpen for the remainder of the 2000 campaign, finishing the year 1-10 with a 7.02 ERA.

That winter brought two significant changes for Johnson that furthered his career. First, believing he was too easily distracted on the mound, he enrolled in focus training at the suggestion of the Orioles vice president of baseball operations, Syd Thrift. Johnson noted that after this training, “I’m able to get in a zone out there where I only see my catcher.”6 Second, after meeting with an insulin-pump manufacturer, Johnson started wearing an insulin pump on days he wasn’t pitching. This led to tighter control over his blood sugars along with an increase in energy. These changes allowed Johnson to spend all of 2001 in the Orioles starting rotation, leading the team with 10 wins and 15 quality starts over his 32 games.

This success was noticed by the Boston Baseball Writers Association and Johnson was awarded the Tony Conigliaro Award for spirit and determination in overcoming obstacles, in Johnson’s case his diabetes. (He shared the award with Graeme Lloyd.) The Orioles also noticed his success, and bought out his first two arbitration years with a two-year, $4.7 million contract. Additional off-field success included being named the Baltimore Orioles representative to the Major League Baseball Players Association.

Johnson was a rotation mainstay for the Orioles in 2002; although two separate DL stints – one for a broken finger and one for shoulder tendinitis – limited him to 22 starts and a dismal 5-14 record. During spring training in 2003, Johnson suffered a hypoglycemic seizure, but did not require hospitalization. He was able to remain healthy for the full season in 2003; Johnson made 32 starts for the Orioles, finishing with a 10-10 record. With his two-year contract expiring, and the Orioles fearing a significant raise in arbitration, he was nontendered and released in December of 2003.

Johnson was not unemployed long, as the Detroit Tigers signed him less than 10 days later to a two-year, $7 million pact. On the advice of Kevin Rand, the Tigers trainer, Johnson sought approval from Major League Baseball to start wearing his insulin pump during games. “When I first got the insulin pump, I figured they’d never let me wear this on my belt,” he said. “No one else in the league had ever worn one during a game, and I thought hitters would complain about it being different and that it would throw them off.”7 MLB did grant approval, and Johnson started wearing the pump during games; moving it to his lower right back to stay out of the way of batted balls.

A strong spring training resulted in Johnson making the 2004 Opening Day start for the Tigers. He experienced some success over his two seasons with the Tigers – highlighted by winning the July 11, 2004, AL Player of the Week Award. He also became the first Tigers pitcher to hit a home run in the DH era, connecting off the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Jeff Weaver on June 8, 2005. Over his two seasons with the Tigers he was an innings-eater, tossing 406⅔ innings over 66 starts, but with an overall record of 16-28 for the second-division club.

Another change of address was in store for 2006 as Johnson signed an incentive-laden contract with the Cleveland Indians worth a guaranteed $4 million for one year; but worth up to $11.5 million over two years. The honeymoon was short-lived however, as he was designated for assignment after going 3-8 in only 14 starts for the Tribe. Claimed by the Boston Red Sox on June 21, he started six games without any more success (he was 0-4), was released, and finished the year with four appearances in the Cincinnati Reds bullpen.

An opportunity across the Pacific presented itself for the 2007 season and Johnson signed with the Seibu Lions of Japan’s Pacific League. Shoulder injuries limited him to a 1-4 record over seven games. Returning stateside in 2008; he pitched most of the year at Triple-A Las Vegas, a Dodgers farm team, but did make it back to the big leagues for 16 games with the Dodgers; including a start of six scoreless innings in his first appearance back.

Signing a minor-league contract with the Yankees for the 2009 season, Johnson hoped to make the big-league club out of spring training, but was diagnosed with choroidal melanoma, a cancerous growth behind his right eye that required surgery and implantation of a radiation plaque. He did pitch in nine minor-league games, but was unable to make it back to the major leagues. He married his second wife, Ember Blueggel, in November of 2009.

After missing the 2010 season with shoulder surgery, Johnson attempted comebacks in the independent leagues with the Camden Riversharks in 2011 and the Amarillo Sox in 2013 but was unable to make a full recovery from the shoulder surgery.

After retiring from baseball, Johnson remained active, living in the Tampa area with his wife and two daughters. He became a certified scuba diver in 2007 and began giving pitching lessons. He became very active in fundraising and education with the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, and has served as an ambassador for MiniMed, a company that manufactures insulin pumps. A role model for those with diabetes, Johnson noted in 2005, “Some people might think it’s a bad break to have diabetes, but I think the disease has affected my career in a positive way. I’m succeeding in life at my chosen profession, and I get a chance to help people too. I tell kids all the time to never give up. Never let anyone tell you that you can’t do something.”8

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Jason Johnson’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, the 2003 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide, and the following articles:

Carig, Marc. “New York Yankees’ Jason Johnson Battling Eye Cancer While Trying to Make Final Roster,” nj.com/yankees/index.ssf/2009/03/new_york_yankees_jason_johnson.html, March 19, 2009, accessed August 6, 2016.

Hawbaker, Karrie. “Behind The Photo: Jason Johnson,” loop-blog.com/minimed-ambassador-jason-johnson/, accessed August 6, 2016.

Nadel, John. “Jason Johnson Pitches Dodgers Past Giants 2-0,” USA Today, usatoday30.usatoday.com/sports/baseball/2008-07-30-2989047442_x.htm, July 30, 2008, accessed August 6, 2016.

Strauss, Joe. “Pumped-Up Johnson Adds Tony C. Award to 10 Wins,” Baltimore Sun, articles.baltimoresun.com/2001-12-12/sports/0112120268_1_johnson-conigliaro-tony-saunders, December 12, 2001, accessed August 6, 2016.

“Jason Johnson Biography,” dlife.com/diabetes/famous_people/sports/jason_johnson_biography, November 28, 2012, accessed August 6, 2016.

Notes

1 Anthony Castrovince, “Diabetes Doesn’t Have Johnson Down,” mlb.com, m.mlb.com/news/article/1383031//, April 5, 2006, accessed August 6, 2016.

2 Ibid.

3 According to baseball-reference.com. Retrosheet.org lists him at 220 pounds.

4 Jason Johnson with Dennis Tuttle, “It’s Always a Roller-Coaster Ride,” espn.com/espn/print?id=2112188&type=Story&imagesPrint=off, July 20, 2005, accessed August 8, 2016.

5 Jason Johnson, telephone interview with author, August 26, 2016.

6 The Sporting News, June 25, 2001.

7 Bill Finley, “BASEBALL; Belt Pump Helps Pitcher With Diabetes,” New York Times, nytimes.com/2004/07/06/sports/baseball-belt-pump-helps-pitcher-with-diabetes.html?_r=0, July 6, 2004, accessed August 6, 2016.

8 “It’s Always a Roller-Coaster Ride.”

Full Name

Jason Michael Johnson

Born

October 27, 1973 at Santa Barbara, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.