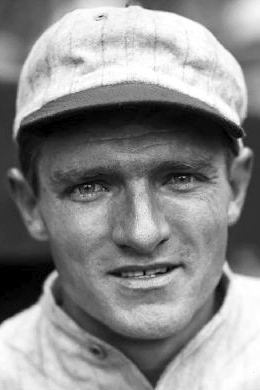

Tom Oliver

Tom Oliver was a terrific defensive center fielder who played four seasons (1930-1933) in the major leagues with the Boston Red Sox. He had great speed, a very good throwing arm, and what his managers called “baseball instincts”, even being favorably compared to the great Tris Speaker. Oliver was one of the few players at the time who could judge a fly ball off the crack of the bat, turn his back, and run to the right spot before turning to make the catch.

Tom Oliver was a terrific defensive center fielder who played four seasons (1930-1933) in the major leagues with the Boston Red Sox. He had great speed, a very good throwing arm, and what his managers called “baseball instincts”, even being favorably compared to the great Tris Speaker. Oliver was one of the few players at the time who could judge a fly ball off the crack of the bat, turn his back, and run to the right spot before turning to make the catch.

The right-handed batting Oliver had a peculiar stance (he faced directly at the pitcher with one foot behind the other) and he was described as an opposite-field, slap hitter. Among 20th century players, he holds the major-league record for most career at-bats (1,931) without hitting a home run. His offensive shortcomings were the primary reason he didn’t spend more time in the major leagues. Over a 20-year playing career, excluding his four years in the majors, Tom played for 18 different teams in nine different leagues. Nicknamed “Rebel”, and retaining a southern drawl throughout his life, Oliver was a true career baseball man, spending nearly 60 years in the game as a player, manager, coach, and scout.

Thomas Noble Oliver was born January 15, 1903 in Montgomery, Alabama to George Mack and Mary Caroline (Powell) Oliver. He had an older brother George, and a younger sister Anna. Tom’s paternal grandfather, Abner Oliver, fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War.1 He graduated from Sydney Lanier High School in Montgomery in 1920 where he was a star baseball and football player. After graduation he worked for three years for a wholesale grocery company while playing on independent city league teams.

In April 1922, Oliver was selected for a city all-star team that played an exhibition game against the Atlanta Crackers. After the game he was offered a contract by Atlanta, but he turned down the offer because the Crackers would have sent him to the Appalachian League. However, Atlanta manager Roy Ellam took the time to meet with the 19-year-old Oliver. He predicted a bright future for the young outfielder and offered a few points on how to make it as a baseball player. Ellam told Oliver, “Don’t drink liquor, keep bad company, or late hours.”2 Perhaps he heeded this advice; in any event, he became successful in baseball.

In June 1922, Oliver had a tryout with the Jackson, Mississippi club, but didn’t make the team. Later that summer he signed his first professional contract with New Orleans in the Southern Association. He was kept on the club’s reserve list for the 1923 season3 but no record could be found of him ever paying for New Orleans. Some sources mistakenly have him playing in Minot, North Dakota in 1923, but this was a player named Harry Oliver.4 Oliver actually broke into professional baseball in 1923 with Laurel, Mississippi in the Cotton States League.

In 1924, Tom had stops in Monroe and Shreveport, Louisiana, before being picked up by the Vernon Tigers in the Pacific Coast League in September. Still the property of Vernon, he began the 1925 season with Decatur, Iowa in the Three-Eye League before being recalled by Vernon in early June. Oliver had his best professional season in 1926, batting .352 for Beaumont in the Texas League. He finished the 1926 season back in the Pacific Coast League with the Mission ballclub and split the 1927 season between Mission and Nashville in the Southern Association.

After three strong seasons in Little Rock (1927-1929), Oliver was drafted by the Philadelphia Athletics. According to the March 29, 1932 issue of the Reading (PA) Eagle, Connie Mack mistakenly thought he was a left-handed hitter (he said he didn’t need any more of them) so he was placed on waivers and picked up by Boston. Oliver knew he couldn’t break into the World Champion A’s outfield of Al Simmons, Mule Haas, and Bing Miller and said, “That’s how close I came to sitting on the bench of a pennant outfit. I got a good break with the Red Sox and was just lucky enough to get a regular job.”5

The Red Sox were coming off an eighth-place finish, but Oliver was the sensation of the spring training camp in Pensacola, Florida in 1930 and quickly clinched the starting center field job. He started the season on a tear at the plate, which included a 19-game hitting streak, batting over .400 the first five or six weeks. He cooled off some but finished the season with a .293 average and led the American League in games played (154) and at-bats (646). In center field, Oliver led the league in putouts (477), a record that stood until it was broken by Dom DiMaggio in 1948, and in fielding percentage. He garnered two A.L. MVP votes.

Oliver had another solid season in 1931, batting .276 and posting career highs in doubles (35) and RBIs (75). He may have had an even better year in the field, leading the American League in center field putouts again (427), and in assists (15) and fielding percentage (.993). He didn’t make his first error until August 29. A decade later, Oliver was asked to compare himself to contemporary center fielders and he said, “Joe [DiMaggio] is probably the best hitting outfielder, but I’ve seen better fielders” naming Sam West, Lloyd Waner, and Terry Moore.6

After the 1931 season, Tom was one of several major leaguers chosen by New York sportswriter Fred Lieb for an all-star tour of Japan. Other members of the team were Hall of Famers Lou Gehrig, Frankie Frisch, Lefty O’Doul, Lefty Grove, and Mickey Cochrane. In dispatches back to the Boston Herald, Oliver said he was amazed at the interest in baseball in Japan “despite hovering war clouds.” His letters talked of his seasickness and complaints about the food and Oliver said, “I could hit their pitching, but had a lot of trouble with those chopsticks.”7

While in Boston, Oliver played between notoriously slow-footed left and right fielders such as Smead Jolley, Dale Alexander, Fatty Fothergill, and Johnny Hodapp. Tom joked that his territory was all the area between the left- and right-field lines and that covering the positions of the poor fielders around him made him too tired to bat any higher. He went on to say, “If I’d received mileage for running in the outfield, I’d have been paid higher than Babe Ruth.”8

Due to nagging injuries in 1932 and 1933, Oliver’s hitting fell off and consequently his playing time was reduced. After several years of second division finishes, Bucky Harris was named the new Red Sox manager for the following season and on November 1, 1933, Oliver was released by Boston to Baltimore in the International League. He started the 1934 season with the Orioles but in June was optioned to Columbus in the American Association. That offseason he was traded to the Cincinnati organization which optioned him to their top minor-league club in Toronto. Tom had three solid seasons (1935-1937) with the Blue Jays.

Oliver started the 1938 season with Knoxville, Tennessee in the Southern Association, but was traded to Montreal in the International League. After 32 games with the Royals, he was traded to Gadsden, Alabama, back in the Southern league. He refused to report to Gadsden, and was suspended by the National Association. Oliver was out of baseball the rest of the 1938 season, but was signed by the Durham Bulls in the Piedmont League for the 1939 season. Durham had a working arrangement with the Cincinnati National League club, and Reds management offered Tom a chance to manage in their organization after his playing days were done.9

In 1940, Tom got his first managing job (he would be a player-manager for several more years) with Reading, Pennsylvania. He led the club to the Interstate League pennant, and continued to play center field, batting .319. But after the season the Reading franchise was sold to the Brooklyn Dodger organization run by Larry MacPhail. MacPhail named his son Lee as business manager at Reading, and the younger MacPhail hired his own manager and let Oliver go.

Oliver quickly got a new job as skipper of the Wilmington, Delaware club in 1941, also in the Interstate League. However, he wasn’t able to play in the field until the end of May due to injuries sustained in a bus accident. Tom suffered cuts, bruises, and broken ribs when the team’s bus plunged down a mountainside on the team’s return from spring training in South Carolina. The next season, 1942, was Tom’s last as an active player. He also managed the Lancaster, Pennsylvania club, an affiliate of the Philadelphia Athletics, in the same league.

Oliver was always proud of the small role he played in the career of Hall of Fame third baseman George Kell. When Kell was released by Durham, an affiliate of Brooklyn, in the spring of 1942, he thought he was out of baseball and was about to go home. Another of the Durham players, Carl Furillo, whom Oliver had managed at Reading, recommended Kell. Oliver was in need of a third baseman at Lancaster because his regular had just been drafted into the Army, so he gave Kell a trial. Kell had a solid season playing for Oliver at Lancaster in 1942, and after hitting .396 in 1943, was purchased by the Philadelphia Athletics, and embarked on his 15-year major-league career.10

Tom enlisted in the U. S. Navy after the 1942 season and served as a torpedo man second-class aboard the destroyer Grayson (DD-435). The destroyer was involved in the Pacific Theater of Operations in the Solomon Islands and Admirality Islands, as well as duty off Saipan and Formosa.11 After the war, he returned to baseball, managing at Lancaster again in 1946. The next year he became a scout with the Philadelphia Athletics and became known as the organization’s “ace troubleshooter.” After the manager of the Athletics’ affiliate in Savannah, Georgia became ill, Oliver took over the club and had the team in first place when the regular manager returned later in the season. Then he was sent to rescue another Athletic farm club in Lincoln, Nebraska. In June 1950, Philadelphia sent him to Fayetteville, North Carolina to take over for manager Mule Haas, who was let go amid a 19-game losing streak.

The Philadelphia Athletics established their spring training base in Palm Beach, Florida in 1945. Soon the club created the Connie Mack Baseball School, which essentially was a three-week winter tryout camp for free agents and rookies. In 1950, Oliver was on “faculty” at the school judging outfielders, while former A’s great Chief Bender was in charge of looking over prospective pitchers.

When Jimmy Dykes took over for Connie Mack as manager in Philadelphia in 1951, Oliver joined the A’s coaching staff. Tom was hit by an errant throw while sitting in the dugout before a game in Detroit in June, 1951 and lost his sight in one eye. He coached in Philadelphia for three years and then followed Dykes to Baltimore in 1954 when he was named to manage the relocated St. Louis Browns. When Dykes was replaced by Paul Richards the next season, Oliver was let go. Tom’s last managerial job was with Fargo-Moorhead in the Northern League in 1956.

After that, he returned to scouting. He worked as a scout for Baltimore, Washington, and Minnesota, and then was the Southeast region scout for the Philadelphia Phillies for 18 years before retiring in 1983 at the age of 80. He returned to Montgomery to live out his remaining years and passed away February 26, 1988, at age 85. Tom was a life-long bachelor, and when asked for an explanation quipped, “I got passed up, nobody drafted me.”12 He is buried beneath a tombstone he shares with his father, at Oakwood Cemetery in Montgomery.

Notes

1 Ancestry.com

2 Montgomery (AL) Advertiser, April 10, 1922.

3 New Orleans Times Picayune, October 8, 1922.

4 Bismarck (ND) Tribune, August 8, 1923.

5 Boston Herald, April 14, 1932.

6 Reading (PA) Eagle, January 17, 1940.

7 Boston Herald, December 31, 1931.

8 Sporting News, April 28, 1973.

9 Greensboro (NC) Record, June 13, 1950.

10 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

Full Name

Thomas Noble Oliver

Born

January 15, 1903 at Montgomery, AL (USA)

Died

February 26, 1988 at Montgomery, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.