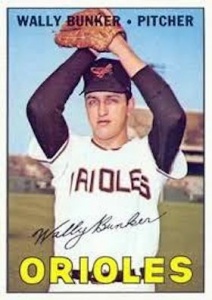

Wally Bunker

“One day you’re skipping school to watch the Giants play in the ’62 Series against the Yankees. … (Two years later), you’re pitching against Mickey Mantle.” — Wally Bunker1

The youngest athlete to garner Most Valuable Player consideration, in 1964 Wally Bunker tied the American League record for most wins by a rookie. Through 2015 he remained the only teenager since Amos Rusie in 1890 to win more than 17 games. Two years later, in 1966, he became the third youngest pitcher to throw a World Series shutout (the second youngest, Jim Palmer, tossed his two days earlier). As the Opening Day starter in 1969, Bunker captured the honor of throwing the first pitch in Kansas City Royals’ history.

The youngest athlete to garner Most Valuable Player consideration, in 1964 Wally Bunker tied the American League record for most wins by a rookie. Through 2015 he remained the only teenager since Amos Rusie in 1890 to win more than 17 games. Two years later, in 1966, he became the third youngest pitcher to throw a World Series shutout (the second youngest, Jim Palmer, tossed his two days earlier). As the Opening Day starter in 1969, Bunker captured the honor of throwing the first pitch in Kansas City Royals’ history.

This description would seemingly describe the exploits of a Cooperstown inductee. When the 18-year-old phenom launched his career in 1963, many thought they were witnessing the beginnings of a Hall of Fame career. But injury would take its toll on the young arm, limiting the right-hander to less than 122 innings per year in four of his last five seasons. He retired at 27 with just 60 wins to his major-league résumé.

Wallace Edward Bunker was born on January 25, 1945, to Thomas Edward and Endla “Virginia” (Bach) Bunker in Seattle, Washington. Bunker was the abbreviated version of Berboncure (or Verboncouer), indicating French-Canadian ancestry; Wally’s three-great-grandfather first used the shortened version after moving to Wisconsin in the mid-1800s. Thomas was born around 1915 in Daggett, Michigan, 80 miles north of Green Bay, Wisconsin, and moved to the Northwest at an early age. The painter/contractor met Virginia Bach, a Washington native of Estonian extraction, and they married on December 12, 1936.

The Bunkers lived just eight miles north of Sicks Stadium, the home of the Pacific Coast League Seattle Rainiers, where proximity alone may have influenced the direction their son took. The mold was furthered when the family moved to San Bruno, California, only 10 miles from the future site of San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. Bunker attended St. Robert Catholic (Middle) School before advancing to the public Capuchino High (fellow alumni include actress Suzanne Somers and ballplayer Keith Hernandez). Bunker was gifted in basketball and baseball, and his prowess on the diamond was evidenced by the major-league scouts who hovered around him as early as his freshman year.2 He was a strong hitter, but the scouts were far more interested in his mound accomplishments. Bunker’s smooth, flowing delivery offered perfect control that contributed to a 16-2 record in his last two years of high school. In an epic 1963 match against future major-league lefty Jan Dukes, the high-school senior pitched 15 innings and struck out 23 in a heartbreaking one-run loss to rival Mills High (a match vividly recalled decades later by those in attendance).

But prep fields were not the only locales on which Bunker excelled. In 1961-62 he pitched in the Peninsula Winter League as “one of the Bay Area’s most promising hill prospects in years.”3 Performing alongside future major leaguers Ernie Fazio, Nelson Briles, and Ron Stone, the schoolboy dominated the circuit. On November 18, 1962, Bunker concluded his semipro career with a one-hit victory in a game in Candlestick Park. He paced the league in wins (7) and ERA (1.25).

In June 1963, after Bunker’s high-school graduation, his father negotiated a $75,0004 bonus for Wally to sign with the Baltimore Orioles.5 Though many clubs were scared away by the expected high bonus, the amount was comparable to what at least nine other clubs were offering. The persistence by Orioles’ scouts Don McShane and Fred Hofmann and farm director Harry Dalton was the clincher. The full-court press included an invitation for Bunker to accompany the parent club during a road trip (presumably the club’s Western swing a month earlier). Bonus in hand, Bunker treated himself with the purchase of a luxury sports car and his father invested the remainder.

Assigned close to home with the Stockton Ports in the California League (Class A) Bunker made an immediate splash: a 0.50 ERA in his first two professional appearances (two complete-game wins, including a shutout over the Modesto Colts). The youngest pitcher on the first-place club, Bunker won six more decisions before suffering his only loss of the season. He placed among the league leaders with 10-1, 2.55 and collected another win in the league playoffs. The only blemish was a yield of 53 walks in 99 innings, a figure that did not prevent the Orioles from wanting an early glimpse of the prized righty.

On September 29, 1963 – the last day of the season – the 18-year-old made his major-league debut, against another teenager, 19-year-old Detroit Tigers pitcher Denny McLain. Bunker retired the first four batters and surrendered just two hits in three innings before the Tigers reached him for two runs in the fourth. Bunker’s undoing came in the fifth when five consecutive hits resulted in a trip to the showers. He took a 7-3 loss. Bunker trekked south to spend the winter in the Florida Instructional League, and placed among the circuit’s pitching leaders.

In 1964 the Orioles faced a serious challenge with Bunker pertaining to the major-league rules regarding bonus babies. Blessed with an abundance of competent hurlers, the club was not prepared to keep Bunker on the roster. But an assignment to the minors risked the near certainty of losing the bonus baby on waivers. Acknowledging Bunker’s “exceptional promise,” Hank Bauer, the Orioles’ new manager, suggested that the youngster might find use “mopping up once in a while.”6 Bunker made management’s choice easier with a superb Grapefruit League campaign. He was flawless against the 1963 World Series combatants: three perfect innings against the New York Yankees on March 14, and three weeks later three scoreless frames versus the Los Angeles Dodgers. The success yielded little immediate return when, through the first weeks of the regular season, Bunker threw nothing but batting practice.

But nagging injuries to Milt Pappas and Steve Barber, two of the Orioles’ frontline starters, forced Bauer to turn to Bunker on May 5. Hoping for four or five decent innings, the skipper was pleasantly surprised when Bunker needed just 99 pitches to deliver a one-hit complete-game victory over the Washington Senators. His ecstatic teammates greeted the unforeseen outing with humor: “[Bunker]’s too young to pitch,” said pitching coach Harry Brecheen. “He should be enjoying ice cream like the other kids.”7 Future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts weighed in as well: “Are you sure he’s only 19? Those Californians are so relaxed they might have lost his birth certificate.”8

In a second start five days later, an unearned run was the only barrier between Bunker and his first major-league shutout. Through May 11 Bunker and Roberts were the only Baltimore hurlers with complete games (two each). Bauer inserted the 19-year-old into the rotation permanently. Bunker, at 5-0, 1.76 through May, earned recognition alongside San Francisco’s Willie Mays for the Van Heusen Outstanding Achievement award for the month. On June 17, the 189th anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill (celebrated as Bunker Hill Day in Boston), Baltimore mayor T.R. McKeldin proclaimed Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium mound “Bunker Hill” after the youngster vaulted the club into sole possession of first place with a win over the Chicago White Sox. “Bunker possesses composure and poise,” gushed Orioles’ scout Jim Russo. “He was born with it, just as Joe DiMaggio was born with gracefulness. … Only once in a long while do you run into a boy like this.”9

On July 3 Kansas City slugger Rocky Colavito’s fifth-inning double foiled Bunker’s bid for a no-hitter as the righty collected his first shutout.10 Bunker did not absorb his first home loss until August 28 as he constructed a brilliant 19-5, 2.69 record.11 Remarkably, he surrendered two or fewer earned runs in three of the five losses. Occasionally criticized for lacking an overpowering fastball, Bunker built his success on a tantalizing sinker that Mickey Mantle described as a pitch “you could break your back on.”12 Bunker tied his childhood idol, Sandy Koufax, for the majors’ highest winning percentage (.792), becoming the first rookie to lead either league since the Red Sox’ Dave Ferriss in 1945. He was named to the Topps All-Rookie squad while earning American League Rookie of the Year and Most Valuable Player consideration. But Bunker’s season ended on an ominous note. On September 25, while warming up in preparation for a start in Cleveland, he felt a sharp pain. “It felt like somebody shot me in the back of the shoulder with a .22,” Bunker related years after. “I’m sure it was that rotator cuff. From then on, it always hurt.”13

The following spring a seemingly clairvoyant sports columnist pondered “[W]hat could happen to Baltimore if [Bunker,] the rookie prodigy … wins ten games instead of 19.”14 Bunker’s 10-8 record in 1965 was preceded by a pain-filled spring training that prevented him from throwing during the first two weeks of camp. He struggled mightily when the exhibition season started: 19 hits and 11 runs yielded in his first seven innings, prompting a public lashing by Bauer. In an effort to lessen the pain, Bunker began changing his delivery to a less-than-overhand approach. (The changed delivery yielded later elbow problems.) He started the season in relief and was unable to get past the fifth inning in his first two starts. Bunker finished April with a 7.16 ERA. Cortisone injections brought some respite. In June Bunker exhibited signs of his rookie success with his second major-league shutout. This was followed by three additional strong outings. But he was unable to sustain the surge. Bunker went winless in six consecutive starts through August 19 and was briefly returned to the bullpen. Seeking outfield help during the offseason, the Orioles shopped Bunker before landing future Hall of Famer Frank Robinson from Cincinnati.

The 1966 season bloomed hopeful for Bunker. On April 29 he dodged numerous scoring opportunities by the Tigers to secure an 8-1 win. Asked how he escaped, Bunker wryly replied, “I go to church.”15 Two months later he carried a no-hitter into the seventh against Boston before settling for a 9-2 win. The addition of Robinson transformed the 1966 Orioles into an offensive powerhouse from which Bunker benefited. On June 25 the righty placed among the league leaders with eight wins despite an unimpressive 3.95 ERA. But the wheels came off in July. Bunker suffered a series of injuries from severe blisters to elbow tendinitis (the latter landing him on the disabled list). Upon his return he was used sparingly, not receiving a start until September. After the promising start Bunker finished with a pedestrian 10-6, 4.29.

On June 13, 1966, the Orioles gained sole possession of first place in the American League. They never looked back as the club chalked up the franchise’s highest winning percentage so far (.606). Despite this success they were deemed decided World Series underdogs against the reigning champion Dodgers. Instead Orioles pitching shattered a 61-year mark with a Series record stretch of 33⅓ scoreless innings, hoisting the Birds to the franchise’s first world championship. Bunker’s contribution came in Game Three: a 1-0 win on the heels of future Hall of Famer Jim Palmer’s whitewash.16 Bunker struck out the first two batters and despite throbbing pain, remained strong throughout. “I remember making nothing but perfect pitch after perfect pitch,” Bunker recalled years later.17 After the Series he returned home to be feted by his hometown: honored as San Bruno’s honorary mayor after a motorcade along the main street.

Upon doctor’s orders Bunker did not pick up a baseball over the offseason. The long rest proved futile when he reported to the Orioles’ 1967 spring training still bothered by the elbow tendinitis. The problem manifested itself in Bunker’s stamina: In nine starts he went beyond six innings just once. Relegated to the bullpen for much of the season Bunker sustained some success: 1-2, 2.77 in relief, 2-5, 5.72 as a starter. In March 1968 the Yankees pursued Bunker in a multiplayer swap involving Yankees lefty Al Downing. The deal never happened. Bunker exhibited signs of a restored wing – including two impressive Grapefruit League outings against the Yankees– before arm problems set in again. On the eve of the 1968 season, he was optioned to the Rochester Red Wings.

The arm rebounded instantly as Bunker collected six straight wins (his only defeat was a shutout by Jacksonville’s Tug McGraw). The stamina issues were still present (just two complete games) but this did not prohibit Bunker’s recall. On June 19 he made his major-league return before friends and family in Oakland. A yield of five hits and two walks in three innings resulted in a quick hook. Six days later he rebounded with a five-hit shutout of the Red Sox. In August Bunker captured another complete-game win, 7-2 over Oakland. He finished 2-0, 2.41 in 71 innings. Bunker was flawless in relief: no earned runs surrendered in 15⅓ innings. Accompanied by a number of Orioles teammates Bunker spent the winter in the Puerto Rican League. In December, under the guidance of Santurce manager Frank Robinson, he placed among the league leaders at 7-2, 1.69. But by this time Bunker was no longer a member of the Orioles.

On October 15, 1968, Bunker was selected by the Kansas City Royals in the major-league expansion draft. The Royals’ John Schuerholz, having come to Kansas City’s front office from the Baltimore organization, played a central role in the expansion club’s selection of a number of Orioles players. (Remarkably, he neglected an unprotected Jim Palmer.) Six months later Bunker was granted the privilege of throwing the first pitch in Royals history. A middling start to the season gave way to two difficult outings that moved him to the bullpen. There he might have stayed had it not been for the tutoring Bunker received from Royals coach Harry Dunlop (the righty’s first professional manager, at Stockton). On May 30, 1969, in his second appearance following recovery from a pulled hamstring, Bunker came within one out of a complete-game win over the Yankees. Four days later he struck out a career-high 10 batters in a complete-game victory over the Washington Senators. Former general manager Frank Lane, who monitored the performance as a scout for the Orioles, remarked, “I’m glad for his sake. … [Bunker]’s a great kid. He does his job and never complains. He’s always ready to pitch. If he can keep throwing like that, he’ll be a winner again.”18

The “veteran presence” of the 24-year-old stabilized the Royals’ staff throughout the expansion season. Bunker’s 12-11 mark was hampered by his offensively challenged teammates: In 14 starts he tossed a 3.03 ERA (league avg.: 3.62) but was winless (0-7). Though he faced his own challenges offensively throughout his career, he took matters into his own hands on August 18 with two hits and three RBIs in a complete-game victory over the Yankees. Three weeks later Bunker flirted with a no-hitter into the seventh against the California Angels, settling for his third career one-hitter. On September 16 he delivered a game-winning double to beat the Seattle Pilots 2-1. Bunker was named the Royals’ Most Valuable Player and drew consideration for The Sporting News Comeback Player of the Year Award. At the end of the season Bunker explained his newfound success: “I’m smarter and have more pitches. I’m not throwing as hard as I did [in 1964] but I’m mixing up the pitches.”19 He bought a home in the suburbs of Kansas City. Bunker spent the winter selling season-ticket packages while the club fended off trade queries for him.

Charlie Metro, the Royals’ new manager, appointed Bunker the Opening Day starter in 1970 provided the righty cut his long hair. But the era’s shoulder-length locks were no competition to the resurfaced shoulder problems that brought an eventual end to Bunker’s career. The ailing wing (compounded by an ankle injury) limited him to just 11⅓ innings over a two-month period. Bunker’s ERA floated above 8.00. He returned in July after consultation with an orthopedic specialist. After some success in relief Bunker was reinstated in the rotation. On August 21 he threw 11 innings of three-hit ball against Boston. Eleven days later, after wiggling out of a first-inning bases-loaded jam, Bunker earned his first win of the season with a four-hit shutout of the Angels. On September 25 he suffered a heartbreaking 1-0 loss in a pitching duel with Minnesota righty (and that season’s Cy Young Award winner) Jim Perry. Despite the late surge, Bunker finished a disappointing 2-11, 4.22.

By 1971 Opening Day starts were a thing of the past. Projected as the Royals’ number-three starter behind Jim Rooker and Dick Drago, Bunker struggled out of the gate and the Royals showed little patience. On June 7, a month after what became his last win in the majors (a 5-2 defeat over his former employer), Bunker was optioned to Triple-A Omaha. In his first appearance (and his first minor-league appearance in eight years) Bunker shut out the Iowa Oaks. Ten days later he tossed a three-hit shutout over Oklahoma City. But far less success followed in July. He finished 2-8, 4.38 in his final 13 appearances.20 At the end of the season Bunker was dropped from the Royals’ 40-man roster. In 1972 he was welcomed to spring camp as a nonroster invitee but did not make the cut. Assigned to Omaha again, Bunker captured the club’s first win of the season as he constructed a possible comeback: 2-2, 2.75 in six starts. In June, after not making an appearance after May 22, the 27-year-old abruptly retired.21

On November 7, 1964, after his brilliant rookie campaign, Bunker had married Kathryn L. Wild – a love affair that began at a school sock hop (she went to a different school) and lasted over 50 years. After Bunker’s retirement the couple moved to the Seattle area, where they raised two sons. (The boys were born while he was still an Orioles hurler.) Bunker took up slow-pitch softball until a hamstring injury ended that pursuit. He began remodeling homes before the artistically inclined couple moved into even more creative endeavors: manufacturing and marketing decorative animal magnets, earthen pottery and painting. They moved from Seattle to Idaho to Ohio and South Carolina, settling for a period in a nature community in the Palmetto State’s Low Country. Bunker became an accomplished pianist and avid kayaker. In April 2015 the couple collaborated on an illustrated children’s book, I Am Me.

On May 25, 1995, the righty who authored one of the finest rookie campaigns in major-league history was inducted into the San Mateo County (California) Sports Hall of Fame. Noted throughout his career for his stoic and unemotional approach to the game, Bunker philosophically reflected on his extraordinary early success: “You get spoiled. … That’s the bad part of doing it when you’re so young. Honestly, it would have been nice to wait two or three years.”22 Bunker concluded a nine year major-league career 60-52, 3.51 in 206 appearances (152 starts). Noted for his control, through 2015 Bunker remained among the top 160 pitchers in career WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) and hits per nine innings.

Last revised: March 17, 2023 (zp)

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank SABR member James W. Johnson for information related to Bunker’s childhood. Further thanks are extended to Rod Nelson, Chair of the SABR Scouts Committee and Len Levin for review and edit of the narrative.

Sources

Ancestry.com.

mercurynews.com/san-mateo/ci_15747896.

weblogs.baltimoresun.com/sports/thetoydepartment/2009/07/catching_up_with_former_oriole_2.html.

prep2prep.com/prepcat/?tag=capuchino-high.

books.google.com/books/about/I_Am_Me.html?id=CwVJrgEACAAJ.

articles.baltimoresun.com/2007-10-06/news/0710060207_1_wally-bunker-dalene-flying-turtle.

youtube.com/watch?v=0Qx8skq8QYk.

royalsauthority.com/top-100-royals-96-wally-bunker-%E2%88%99-rhp-%E2%88%99-1969-71/.

Notes

1 Jeff Faraudo, “Bunker was a battler on the hill,” Inside Bay Area (March 5, 2008) (insidebayarea.com/turn2/ci_8460111).

2 Fearing injury to the young phenom, scouts dissuaded Bunker from playing football.

3 “17-Year-Old Hill Phenom Notches Four-Hit Shutout,” The Sporting News, October 13, 1962: 30.

4 The figure is variously presented as low as $40,000, as high as $80,000.

5 The Orioles wrestled with a choice of Bunker or Baltimore product Dave Boswell. The club soured on Boswell after a dismal senior year in high school.

6 “Orioles’ Mound Problem Unique – Too Many Men,” The Sporting News, March 14, 1964: 18.

7 “Diamond Thrills Cop 1964 Blue Ribbon,” The Sporting News, January 2, 1965: 29.

8 “Vet Roberts Pulls Out All Stops in Saluting Bunker,” The Sporting News, September 19, 1964: 4.

9 “Boy Wonder Bunker – Big Man on Hill,” The Sporting News, June 20, 1964: 3.

10 A lifetime .129 hitter against Bunker, Colavito foiled another shutout bid on July 31 with a seventh-inning homer.

11 Through 2015 the 19 wins remained an Oriole rookie single-season record.

12 Jeff Faraudo, “Bunker was a battler on the hill.”

13 Ibid.

14 “Soph Jinx May Torpedo Flag Contenders,” The Sporting News, March 27, 1965: 1.

15 “’Old Maid’ Hurlers Say, ‘We Do’ – Hank Blushes Fetchingly,” The Sporting News, May 14, 1965: 5.

16 Neither pitcher had a shutout during the regular season.

17 Jeff Faraudo, “Bunker was a battler on the hill.”

18 “Bunker Pumping Fast Ball Again; Royals Rejoice,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1969: 20.

19 “Bunker and Piniella Win Royal Laurels For Super Showing,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1969: 16.

20 Though he did collect his first professional homer on August 8, a three-run shot against the Denver Bears in an 8-2 win.

21 The author was unable to confirm it but it appears the lingering arm problems contributed to the sudden decision.

22 Jeff Faraudo, “Bunker was a battler on the hill.”

Full Name

Wallace Edward Bunker

Born

January 25, 1945 at Seattle, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.